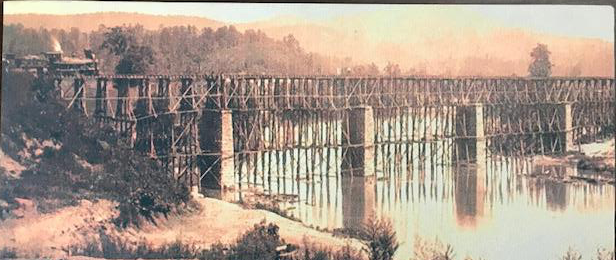

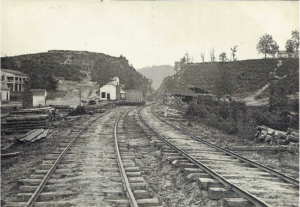

Etowah Station, W&A RR Etowah River Bridge

The History and Development of the Railroads of Bartow County

By Giovanni Martino

Bartow County, formerly Cass County, owes much of its success to the early construction of a state-owned railroad built between Atlanta and Chattanooga known as the Western and Atlantic (W&ARR). Being situated at the midpoint of these two termini, Bartow County’s citizens wasted no time in improving their

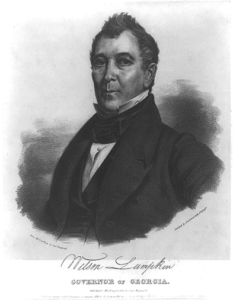

Wilson Lumpkin, 35th governor of Georgia and the man most responsible for the prominence of its rail system.

fortunes through the railroad. The county is located in a fortuitous geographic position; iron is abundant in its eastern mountains, while much of the north and west of the county is well-suited to use as farmland. Iron goods and agricultural products produced in Bartow were within a few days’ shipping to any market in the nation. As well, the area had an early boost in population from settlers seeking gold, minerals, and land on which they might establish a new life for themselves. Such success would lead to the construction of multiple other railroads, leading from Bartow to various other cities and towns throughout northern Georgia and Alabama.

As a result of the initial state owned W&ARR, local Bartow entrepreneurs eventually built five railroads and supporting spurs that connected to the state road. Additionally, interstate railroad companies would also come to share the tracks creating a thriving network of rail traffic. These various railroads contributed greatly to Bartow’s status as an economic power in Georgia.

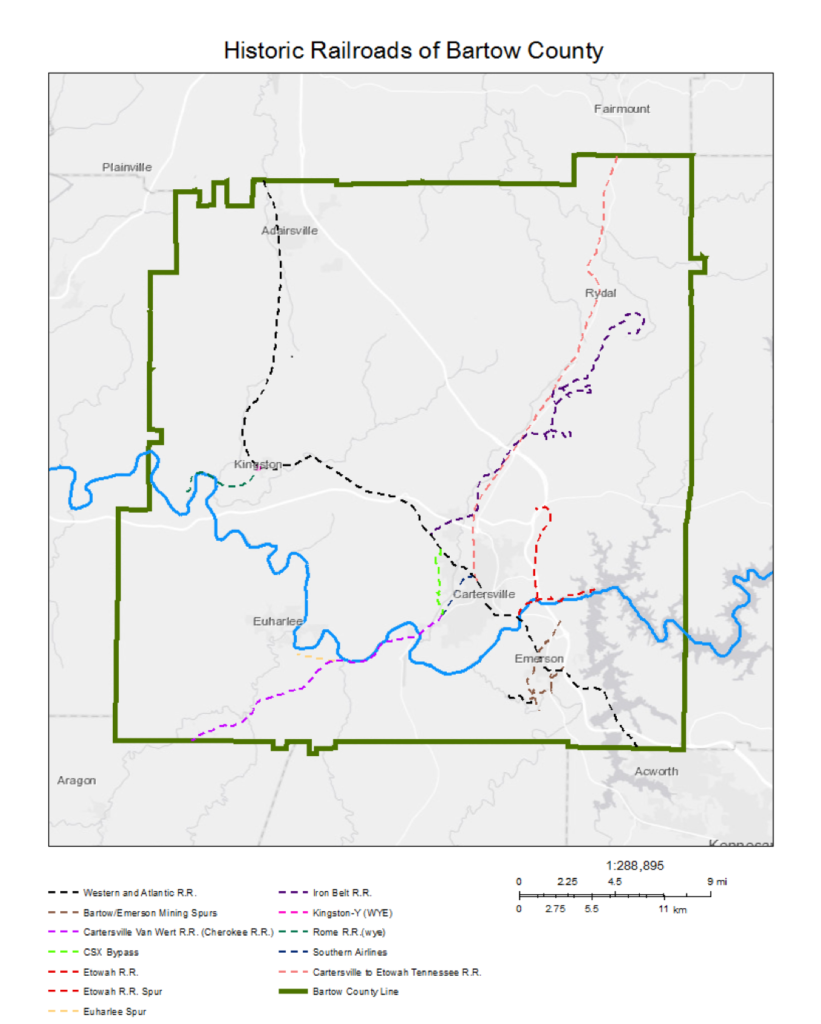

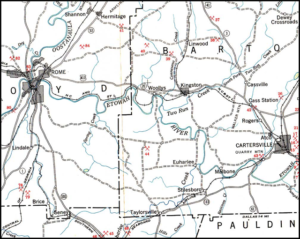

Map Courtesy of Josh Shapiro and Tim Poe via ArcGIS

The Western and Atlantic Railroad

In 1826, Wilson Lumpkin accompanied surveyor Hamilton Fulton in an expedition to choose the route for a proposed canal meant to link the Chattahoochee and Tennessee rivers. Due to the great distance and significant number of mountains in-between the two locations, Fulton dismissed all possibilities for a canal as entirely infeasible. However, he did lay a suggested path for a railroad in the area. Railways were, at this time, a new technology, unfamiliar to most of America.

Lumpkin was elected governor of Georgia in 1831. A few years earlier, in 1829, gold had been discovered near Dahlonega. The area surrounding Dahlonega was, at the time, owned by the Cherokee Nation. Acutely aware of the potential economic benefits of this land, Lumpkin authorized a survey of Cherokee lands, disbursing the lands despite the continued presence of Cherokees. To remedy this, Lumpkin became an advocate of President Jackson’s Indian Removal act, forcing the Cherokees to walk the “Trail of Tears” out of Georgia.

In September 1831, several prominent citizens of Georgia met in Eatonton to discuss the funding and location of potential railroads. This meeting stimulated demand for railroads in Georgia; three railroads were chartered by the Georgia State Assembly in the legislative session of 1833 (The Macon and Western Railroad, the Central of Georgia Railroad, and the Georgia Railroad), all in the east or south of the state.

Colonel Steven Harriman Long, the man who surveyed the original route of the Western and Atlantic RR

These new lines would have to be connected with the greater network of railways shared by other states. On December 21, 1836, the State Assembly of Georgia voted to fund the construction of a railway line linking these southern roads to Chattanooga. Col. Stephen Harriman Long, was contracted for the Survey on May 12, 1837. He located an optimal spot for the joining of the Macon-Savannah Railway with the newly proposed State Road. This terminus would be located about seven miles to the east of the Chattahoochee River. Not long after Col. Long completed his survey, construction on the line began northward. Over the course of the railway’s construction, the terminus slowly became a township, named Terminus, which eventually became Atlanta.

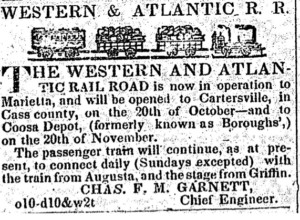

Cass County, being situated halfway between the new terminus point and the city of Chattanooga, became the midpoint of this new rail line. Construction of the newly-christened Western and Atlantic Railroad rail line began in March, 1838. By 1841, only 20 miles of track had been lain, and the W&A did not yet reach Marietta from its terminus in Atlanta. On December 4, 1841, the state legislature voted to suspend all work on the road north of the Etowah River.

This state of affairs would not last for long. Less than a month later, in January 1842, Wilson Lumpkin, now freshly retired from the U.S. Senate, was given the duty of directing construction of the railway. By January 1843, the train line was past Marietta and well on its way to Cassville. On December 22, 1843, the Georgia Legislature approved plans to resume construction north of the Etowah River.

This newspaper clipping reveals the date that railroad service first opened to Cartersville. Note the early, John Bull-esque style of locomotive depicted in the illustration.

The work continued, but stalled at Chetoogeta Mountain (Catoosa County) until a tunnel could be dug. While waiting for the tunnel, the Georgia work crews moved north to Chattanooga and began constructing the rest of the line southward. The tunnel was completed on May 7, 1850[1] and the two lines were joined. The Western and Atlantic Railroad (W&A) was finally completed.

Over the course of the Civil War, the W&A suffered greatly at the hands of both sides. Most of the road’s bridges were destroyed by sabotage multiple times throughout the war. As well, much of the line’s rails were deformed into “Sherman’s Neckties” by heating them and twisting them around trees. This practice was exercised upon the W&A by both the Union, during Sherman’s siege of Atlanta, and the Confederacy, during the course of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign.

After the war, repairing the railroad damage was a primary concern for the Georgia state government, as the W&A was the major artery by which Georgian goods reached the markets of the North. Under new governor James Johnson, the railroad was fully repaired and operational by the end of 1866.

In 1870, by act of the General Assembly, Governor Rufus Bullock leased the W&A to a company owned by former Governor Brown for a period of twenty years, at a rate of $25,000 per month. Brown’s company further helped to restore the railroad to the condition it was in prior to the Civil War, fostering economic development along the road and relieving the state of the financial burden of its management. His lease ran out in 1890; it was not renewed. Instead, the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railway (NC&St.L), a subsidiary of the Louisville and Nashville Railway (L&N), picked up the lease at an increased rate of $35,000 per month for a term lasting thirty years.

Despite the name, the NC&St.L did not actually reach St. Louis, only controlling a line from Chattanooga to Nashville, and from there to Hickman, Kentucky, on the Mississippi River. Still, by extending its line to Atlanta via the W&A, it gained a great influx of wealth. Much of this wealth came from Bartow County, sharing in the spoils which the expansive track of the NC&St.L and L&N afforded its cargo.

It was typical in the south that railroads were built as a broad gauge system meaning five feet between parallel rails. Northern rail systems were four feet, five and half inches. This narrow gauge proved to be more favored and touted as an economic advantage for the rail industry. As a result, in 1886 Georgia adjusted the 138 miles of W&A track in just 24 hours using 400 men who pried up one rail and moved it three inches closer to the opposite rail. Existing rolling stock wheel bases were re-gauged to comply with this change.

In the wake of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the US Army Corps of Engineers, empowered by the Flood Control Act of 1941, set about plans to construct a dam in southeastern Bartow County. As a matter of course, this dam would flood much of that portion of the county. Unfortunately for the NC&St.L, several miles of the W&A were now in an area that was slated to be flooded within a few years. The entry of the United States into WWII set back the timetable quite a bit, but it was still an issue that had to be addressed. So it was that, on March 8, 1945, the Georgia State Assembly passed a resolution providing funding for the relocation of 5.25 miles of track, from where the rail line met the Bartow/Cobb County line to slightly south of Emerson. This track was both to be relocated slightly westwards (to higher ground), and straightened out, as its path was rather meandering. It is not clear precisely when this movement was completed, but it is known that it was finished by the time Allatoona Dam opened on January 31, 1950.

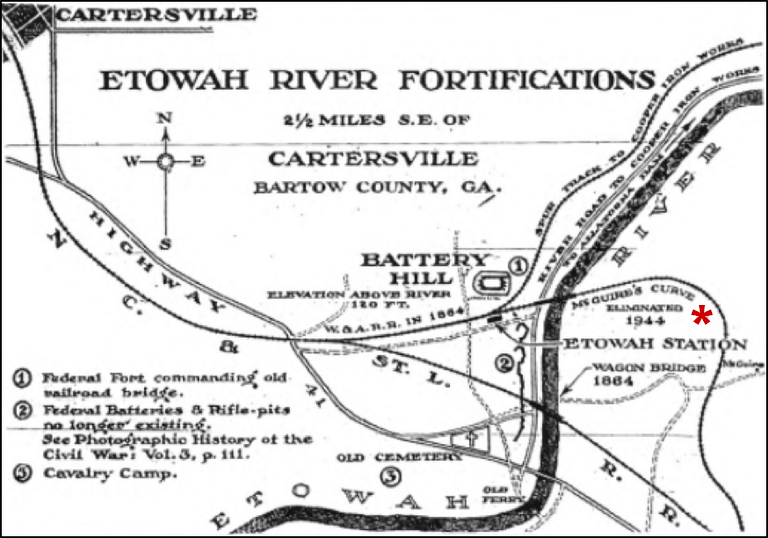

This was not the only track relocation going on in Bartow in the 40’s. Until this time, trains traveling on the W&A would, about two miles north of Emerson, have to go around a broad, sharp turn (almost a right angle) known as “McGuire’s Curve,” after a family living nearby. It is likely that this inelegant bend was the result of the cessation of all work on the original W&A line north of the Etowah River in 1841. When the work picked back up, they chose a slightly different path, and instead of tearing up a mile of track to straighten the whole thing up, they simply continued from where they were, despite the extension in track length.

Regardless of its origin, McGuire’s Curve had to be corrected – which, in 1944, it did. Track connecting the two extreme ends of the curve, essentially the hypotenuse of the triangle, was laid, and the old track of McGuire’s curve was eliminated. Though this task was, presumably, rather notable in scale, it is unclear precisely who authorized and paid for the track movement. No record exists in the State legislative archives providing for the removal of McGuire’s Curve.

The W&A would continue to be leased by the NC&St.L until 1957, when the NC&St.L was absorbed by the L&N. The L&N continued to operate the W&A for another ten years, until its parent company, the Atlantic Coast line (ACL) merged with the Seaboard Air Line (SAL) to form the Seaboard Coast Line (SCL) in 1967. This line itself would merge with Chessie Systems in 1986, forming it current lessee, Chessie-Seaboard Consolidated, better known today as CSX.

Published in a 1949 edition of The Weekly Tribune News, this Wilbur Kurtz illustration depicts the W&A with and without McGuire’s Curve. *

The Etowah Railroad

The work on the W&A brought economic life to Cass County. In 1830, its population was below 2,000 (non-Indian). By 1840, it had skyrocketed to 9,400, reaching 13,300 by 1850.

In 1837, Jacob Stroup and his sons constructed several iron furnaces along the banks of the Etowah River and its local tributaries. Mark Anthony Cooper, a banker from Columbus and organizer of the conference at Eatonton, purchased interest in their ironworking operations in 1842. Shortly afterwards, in 1845, the township of Etowah was founded, based around the ironworks. Seeking a more efficient way to transport locally produced iron, Cooper used his connections in Milledgeville to get a charter for a new spur of the W&A in late 1847. This line, called the Etowah Railroad, was intended to begin at the Etowah Station of the W&A, head through Cooper’s iron works, stretching all the way to Canton and then Dahlonega. The line never made it much farther than Etowah, and construction ceased entirely on the line by 1857. The small portion of the railway which was constructed ran about four miles along the north bank of the Etowah River, between what is now US Route 41 and Allatoona Dam. The junction was just to the southeast of Cartersville, and the terminus was located in Etowah. The locomotive Yonah was acquired to make the rounds, and a turntable was built at the end of the line to service it.

With such investment, the town was an economic boom for several years. Cooper was an effective executive of the town; under him, it became the single most fruitful iron producer in the state of Georgia. Ore processed at its furnaces would go on to constitute the rails of at least three of the major railroads in Georgia (among them the Western and Atlantic). Despite a smallpox scare in 1849 and the destruction of Cooper’s mansion by fire in 1857, the town would remain prosperous for some time. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Etowah was shipping over sixty tons of raw iron and two tons of iron castings monthly. When the war began, the Confederacy wasted no time in pressing the ironworks into service as a munitions foundry. Cooper, though enthusiastic about helping the Confederacy, refused to cease production of his more profitable civilian contracts in favor of the military ones. Seeking a quick resolution, the Confederacy purchased the iron works from Cooper for $400,000 on August 26, 1862.

These pillars, which formerly held a bridge over the Etowah river, are most of what remains of the Etowah Railroad

Due to its status as a Confederate munitions plant and store, the town of Etowah suffered tremendously at the hands of Union troops. Forces under Brigadier General Jeff C. Davis (no relation to the President of the Confederacy) torched much of the town, including all of its various mills. They destroyed the railroad bridge across the Etowah River, as well. With the loss of so much infrastructure,

Etowah was essentially abandoned after the Civil War. Attempts to revive its once-prosperous iron works and mines proved unprofitable. The US Army Corps of Engineers chose Etowah as the location of Allatoona Dam, which, once the dam opened in 1950, flooded most of the ruins as well as the nearby town of Allatoona.

The Rome Railroad

The Memphis Branch Railroad & Steamboat Company was incorporated in 1839, with the goal of constructing a branch from a point on the W&A (later chosen as Kingston) to the city of Rome, where the Etowah River joins the Oostanaula and forms the Coosa River, and beyond, to the Alabama line. The intent of this rail was twofold; first, it would bolster the economy of Rome and Floyd County in general by giving them a link to the rest of the country. Second, it was hoped that constructing a railroad to Rome would foster steamboat traffic to the city by giving them a place to exchange their goods with the Western and Atlantic. The Legislation that created the railroad provided dispensation for the creation of “canals, dams, locks, jets, and all other works that may be required for steam navigation.” Due to the small size of the river, only one steamboat, the diminutive USM Coosa, would operate on the river during antebellum years. No more than six would ever operate the river simultaneously.

This map shows the entire length of the Rome Railroad, from Rome to Kingston, as well as much of the W&A in Bartow County.

Construction of the 18-mile route began in 1848 and was finished in 1849, with its western terminus in Rome and its connection with the W&A at a newly created wye in Kingston. Spurring this rapid progress on the road was its corporate takeover by two individuals: William R. Smith and Alfred Shorter (later of Shorter University fame). These two men revitalized the company, and worked closely to ensure that it was a successful venture. Despite (or perhaps because of) their business acumen, the intended extension of the road from Rome to the Alabama line was never completed. The two businessmen bought only two locomotives to service the Kingston line. Both engines were named for the proprietors of the railroad.

Money brought in by the newly christened Rome Railroad caused a rapid industrialization in the town of Rome. As had happened at so many places across Cass, an ironworks popped up along the banks of the Coosa River. For several years, the Rome-Kingston railroad was the only major artery for shipping out of Rome, though it was eventually joined by the Atlanta North District line, which runs from Cohutta to Atlanta. The influx of goods and money from Floyd County and Rome proved to be a great economic boon to Cass. In 1850, the name of the line was officially changed to the Rome Railroad, though locals of Bartow would come to refer to it as the Rome-Kingston line.

The NC&St.L purchased the Rome-Kingston Line in 1896, shortly after they acquired the lease of the W&A. It proved to be consistently unprofitable for its owners. Despite a campaign launched by the city of Rome to save the railroad, The NC&St.L abandoned it in 1942.

The Civil War

On April 12, 1862, Union spies led by James Andrews hijacked the locomotive General at a breakfast stop in Big Shanty (now Kennesaw). The raiders ran north in hopes of burning bridges, cutting telegraph wires and disrupting rail traffic on the Western and Atlantic Railroad. This plan’s goal was to buy Union General Ormsby Mitchel time to attack Chattanooga and prevent its confederate garrison from receiving reinforcement. The raiders were quickly discovered, and the original engine crew of the General (consisting of conductor William Fuller, engineer Jeff Cain and foreman Anthony Murphy) gave chase by foot and handcar. As the county with the greatest track distance of the W&A, it is only natural that many of the notable events of the chase

It was at Adairsville station that Fuller commandeered the Texas

occurred in Bartow. The General was side tracked for an hour in Kingston by station agent Uriah Stephens, which gave Fuller ample time to catch up. At Etowah station, Fuller commandeered the Yonah; he would abandon it at Kingston in favor of the William R. Smith, but that, too, had to be abandoned due to sabotaged track. Walking to Adairsville, the conductor commandeered the Texas, which served for the rest of the chase. Fuller, joined by locals at multiple points along his journey, had a party of over 30 men on the Texas by the time the General ran out of steam north of Ringgold. There, the raiders dispersed into the night, though all were soon captured by local confederate forces.

After their capture, eight of Andrews’ twenty-two raiders (including Andrews himself) were executed on espionage charges, while the others escaped or were used in prisoner exchange. Most of Andrews’ raiders would later be awarded the nation’s first Medals of Honor for their actions. The events of the Andrews Raid would later be made into two films: The General, starring Buster Keaton, in 1926, and Disney’s The Great Locomotive Chase, starring Fess Parker, in 1956.

After the Civil War, there was much reconstruction to be done in the rechristened Bartow County. The county was directly in the path of Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, and the effects were evident. Two rail depots, one in Cartersville and one in Etowah, were utterly destroyed by the war. The depots at Adairsville, Kingston, and Cassville Station required extensive repairs, which were not finished until 1867. The Union Army had seized control of the W&A and all its spurs from September 1864 to September 1865, causing the loss of an entire year’s worth of revenue. Perhaps the most devastating blow the county suffered was at Cassville, which was burned nearly to the ground. It was not rebuilt, and the county seat, as well as many of the town’s skilled laborers, moved to Cartersville.

The Cartersville and Van Wert Railroad

In the wake of so much destruction, many businessmen saw opportunity. In 1866, the Georgia legislature, under the Radical Republican (“Carpetbagger”) governor Rufus Bullock, chartered the construction of a new line, entitled the Cartersville & Van Wert Railroad. This line was planned to run westward from Cartersville, through a township called Van Wert in Polk County, ultimately terminating at Prior’s Station, GA, on the Alabama state line. The railroad was intended to connect the Western and Atlantic (at Cartersville) with the Selma, Rome, and Dalton Railroad, which ran through Prior’s Station. The route was graded, and construction reached as far as Taylorsville, 14 miles in length. It was at this time, in 1871, that a political scandal in Bullock’s administration forced his resignation. Most of the railroads created under his governorship were reorganized and sold off, among them the C&VW, which was renamed the “Cherokee Railroad”. Former superintendent of the W&A, Edward Hulbert, was appointed as director.

Hulbert was a proponent of the “Narrow gauge”; a 3-foot railway width, as opposed to the 5-foot “Russian gauge” which was prevalent in the South at the time. Like other narrow-gauge advocates, Hulbert opined that that, as the rail would be thinner, so too would the rolling stock using the rails, allowing for drastically reduced costs in construction and maintenance of the rails and railcars. At his urging, the Cherokee Railroad’s construction continued from Taylorsville using the narrow gauge. The first 14 miles of track remained in the broad Gauge. This break in gauge contributed to a bankruptcy of the road in 1873. The railroad went through a succession of owners through the 1870’s, before ending up in the hands of the Cherokee Iron Company (CIC) in 1879. The CIC decided to continue building the

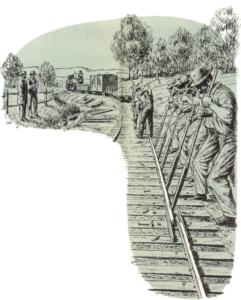

Found in a 1966 issue of Southern Railfan, this illustration depicts how railroad gauges were changed: Crews of men would unbolt one rail, and move it a few inches, as required by the new gauge

railroad, which had stalled at Rockmart for the past decade. Instead of using the original plans and building to Prior’s Station, it was decided to extend the road to Cedartown, where the CIC was headquartered. As well, the CIC converted the Cartersville-Rockmart portion of the

line to narrow gauge in October 1880, and used the station at Cartersville to transfer loads in-between the W&A’s broad gauge and the Cherokee’s narrow gauge. In 1881, the Cherokee Railroad was leased to the East &West Railroad of Alabama (E&WoA) for a period of ninety-nine years. In 1883, the Cherokee was extended to Esom Hill, on th e Georgia/Alabama border, where it was connected to the E&WoA’s existing line. The Cherokee Railroad was then absorbed into the E&WoA. It connected with the Atlanta & Birmingham railway at Pell City, which shortened the journey from Cartersville to Birmingham (and, by extension, the gulf coast at Mobile) by several hundred miles.

Despite the connection, the E&WoA failed to see commercial success. It was sold to a private investor, Charles Ball, on March 16, 1888. Ball converted the line from narrow gauge to the 4’9” inch gauge in 1890. This did not improve the Railroad’s fortunes, and the line was bought under foreclosure by Eugene Kelly on May 29, 1893. He reorganized it as simply the East & West Railroad (E&W), and sold it to the Seabord Air Line (SAL) in 1902. The SAL constructed a new rail line, the Chattahoochee Terminal Railway, from Rockmart directly to Atlanta. As mentioned previously, SAL merged with the ACL in 1967, and the resultant company, SCL, merged with Chessie systems in 1986 to become CSX, which owns the C&VW track to this day.

The Iron Belt Railroad

Chief among the mineral wealth in Bartow’s eastern mountains is a massive deposit of limonite ore, one of the largest in Georgia. As a natural consequence of this fact, several mines have been built in the area. Ore transportation using traditional hauling methods, such as the horse-drawn wagon, was not keeping up with the output of the mines in the late 1800’s. Joseph Brown, now President of the W&A, owned or invested in many of these mines. Using his position, Brown had a rail spur of the W&A extended out from Rogers’ station to the Guyton’s mine, three miles to the east. The presence of this spur greatly increased the rate by which ore was transported from these mountains. Over time, more spurs would be built, and the Rogers-Guyton trunk line was extended as far as Sugar Hill.

The Iron Belt would operate through the turn of the century. Its most common cargo was, naturally, iron ore and mining equipment. As to its passengers, the most frequent were leased convicts from the state prisons, sent to work long hours in the dangerous mining conditions at little to no pay.

The Etowah-Cartersville “New Line”

In 1902, the parent company of the NC&St.L, the L&N, acquired the Atlanta, Knoxville, and Northern (AK&N), which ran from Marietta, GA, to Etowah, TN (Not to be confused with the Etowah village in Bartow County). The AK&N had to navigate several mountains, and was viewed as inefficient by L&N. Intending to bypass the “Old Line”, L&N built a line from Cartersville to its depot at Etowah. This “New Line” (ECNL) would not have to cross over nearly as many mountains as the Marietta route, greatly speeding the route from Atlanta to Cincinnati. The maiden voyage of this track would be undertaken on March 1, 1906, as reported in The Cartersville News and Courant.

The Cartersville end of the line was placed slightly north of the W&A station in downtown Cartersville. This terminus’s location, and the community which would surround it, quickly came be known as “Junta”[2] by Bartow residents, appearing as early as the 1915 Hudgins’ map.

As with most of the railroads throughout Bartow, the ECNL would go through a succession of owners through its years. Built as a line of the L&N, it would, after the merger which created the SCL (outlined in the W&A section), come into the ownership of CSX, who still maintains it today.

Railroad Spurs

A railroad cannot function as a monolith; the main line of the road, in all cases, must be supported by smaller side tracks, which may have a variety of purposes.

Spurs such as this one, captured in the 1910’s, were the primary method by which Bartow county mining companies brought their ores to market

The most common reason to create one of these side tracks – a “spur” – is maintenance. If a locomotive is failing, and is carrying several dozen cars being it, it needs to have a place where it can “pull over” and get out of the way of traffic on the line. Aside from upkeep, spurs are also constructed for economic purposes. They might, for example, be constructed to provide easy access to a factory, a foundry, or a mine. The last of these examples is of particular note to this subject – Bartow County was, for much of its history, rife with mining spurs, branching off of the county’s various rail lines to reach the many mines in the south and east of the county.

As an example, one might examine the spurs which once existed in Emerson. Most prominent among these were those owned by the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI), a major American steel manufacturer working across the Southeast. TCI’s spur snaked through many of the company’s small operations in the area[3], before linking with the W&A near Emerson station. It is unclear precisely when the TCI removed its tracks, but the better part of them likely left along with most of the iron industry of the county, around the end of the 1920’s.

As mentioned, mining spurs were not the only side tracks in Bartow County. Aside from the aforementioned maintenance tracks, which are lo0cated across the county, two specific spurs come to mind. First is the CSX Bypass, built between Cartersville and Stilesboro by CSX to help supply Georgia Power plant Bowen with coal. Second is the old Rowland spur, built north from Etowah station to support both the Dobbins mine, and to help ferry guests to the old, now-defunct Rowland Springs resort.

Proposed Railroads of Bartow County

Since its founding, no less than six railroads were completed in Bartow County. For every one of these, at least two more were successfully approved by the state assembly, yet failed to get off the ground. The reasons for these failures are numerous, but they largely boil down to either a lack of investors or the proposed route of the rail line being overly lengthy or through impassible terrain. It has also been pointed out that several of these railroads might never have been intended to get off the ground in the first place, and served simply as means for their founders to relieve overenthusiastic investors of their income. The lion’s share of these failed extensions date from the 1880‘s.

The first of these failed projects, and the only antebellum one, was the Alabama and Georgia Railroad Company (A&G). In 1850 the Assembly authorized the A&G to extend their line from a proposed terminus on the Georgia-Alabama border through to Cartersville. The A&G, which had been incorporated in Alabama in 1849, had yet to begin building from its intended terminus in Jacksonville by the time it was approved in Georgia. According to the bill, the A&G had ten years to finish this proposed extension. This time was exhausted without success.

Three railroads were proposed during the 1870’s. The first of these was the Atlanta and Blue Ridge Railroad Company (A&BR), incorporated in 1870. Notably, both Governor Brown and Mark Cooper had stakes in this railroad, which was to run from Cartersville to the North Carolina state line in Rabun County. Presumably due to the prevalence of mountains in the land prescribed for this route, the line never saw the light of day.

The Lookout Mountain Railroad Company was formed in 1870 as well. Despite its name, the line was not intended to run north toward Tennessee, but westwards, to the mines of Chattooga County, from the junction at Kingston. It is unknown precisely why this railroad failed, though it may have something to do with the fact that Kingston already had a functioning west-bound route in the Rome Railroad.

Incorporated in 1872 by 38 investors, 23 of whom were from Bartow County, the North Georgia and Ducktown Railroad was intended to run from Cartersville in a northeasterly direction, to the Tennessee border. As its name suggests, the route was meant to reach Ducktown, Tennessee, which – at the time – was the site of a bustling copper industry. The name of the railroad was changed to the “Iron Valley Railroad” in 1875, though no work had yet been done. For that matter, no work would ever be done on this railroad, as it entirely disappears from the record following that name change. What, precisely, caused the failure is unknown, but it is likely that (once again) the presence of mountains in the path of the road prevented any progress.

On September 30, 1881, the Georgia Legislature incorporated the Etowah and Blue Ridge Railroad (E&BR), intended to run from Cartersville to Gainesville. Gainesville was, at the time, home to a station on the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad (ETV&G) a line running through much of the east coast. This made a link to Gainesville highly desirable to the people of Bartow. That being said, there was one severe impediment to any attempt at building a railway between the two cities, an impediment referenced in the E&BR’s name: mountains. Building a railroad through a mountain range is a tricky task; tunnels are expensive and time-consuming to build, and constructing switchbacks and spirals to go around mountains increases track length and danger dramatically. Predictably, the E&BR never materialized.

It was merely the first of seven “Gainesville Routes” to be proposed over the course of the 1880’s. Shortly after the E&BR’s incorporation, a second route, the Kingston, Walesca, and Gainesville Railroad (KW&G), was approved by the Georgia Legislature. As its name suggests, it was to run from Kingston, to Walesca*, to Gainesville, with a stop in Canton along the way. In 1885, another road, the Gainesville and Western (G&W), was chartered to run westwards from Gainesville, “crossing the Western and Atlantic,” the most likely point for the crossing being in Bartow. On December 20, 1886, The Rome and Northeast Railroad (R&N) was incorporated with a charter to run from Rome to Gainesville through Bartow County. Four days later, on December 24, 1886, two separate railroads were chartered to lay track from Bartow County to Gainesville. First, the Rome and Decatur’s (R&D, Inc. 1883) charter was amended to extend its line – whose track was only just being laid – from Rome to Gainesville via Bartow. Second, the Cartersville and Gainesville Airline (C&G) was incorporated to lay track from Cartersville to Gainesville. The last of the Gainesville routes, the Fort Payne and Eastern, was incorporated 1889, to run from Gainesville to the Alabama line, passing through Bartow. Not a single one of these railroads ever materialized.

There was a third railroad incorporated for Bartow County on Christmas Eve, 1886: The Salt Springs North and South Railroad (SSN&S). It was intended to run from either Cartersville or Marietta down to Salt Springs in Douglas County (now known as Lithia Springs). There, it was to connect with the Georgia Pacific Railway (GPR). Upon the railway’s completion, it was to be given the option of extending its line several hundred miles northeastward, all the way to the Tennessee border in Fannin, Union, or Towns Counties. As Cartersville and Marietta both had functioning southwest routes at the time, it should come as little surprise that the SSN&S was never built.

Two decades before the Etowah New Line was constructed, Bartow county investors incorporated a rail line that was to run along a very similar route. This line, the Cartersville, Marysville, and Knoxville Airline (CM&K) was approved by the State Assembly in 1887. Similar to the ECNL, it was intended to run from Cartersville, through Gordon, Murray, and Fannin Counties, up to the Tennessee border, where it would – presumably – have continued on to Marysville and Knoxville. Unlike the ECNL, this railroad was never constructed. Two years later, the Legislature chartered Fairmount Valley Railroad (FMV) with an identical route. It suffered an identical fate.

By act of the State Assembly, the Union Railroad and Transfer Company (UR&T) was incorporated September 2, 1889, with the power to create a small line connecting the R&D and the R-K within the city limits of Rome. As well, contingent upon the line’s completion, the Assembly authorized the UR&T to extend its line to the North Carolina border, passing through Bartow County. For whatever reason, the investors of this rail line failed to fund the miniscule length of the initial proposed track, and it was never constructed.

Finally – and most uniquely – on November 11, 1889, the Georgia State Assembly passed the charter of the Cartersville Street Railroad (CSRR). Streetcars were, at the time, in vogue throughout America and Europe. Atlanta’s first streetcar (horse-drawn, which was common at the time) was installed in 1871. Other, steam-powered ones would pop up not too long afterwards. The proposed CSRR had a dealers’ choice in its method of locomotion – with its charter stating that it may “operate, by horse power, steam power, electricity, or such other power as may be suitable for its purpose, a street railroad in the city of Cartersville.” The route, too, was not set in stone, with the act merely stating that the railroad should run “upon such streets, ways or routes as the Mayor and Council of [Cartersville] may consent to.” There is no official statement of why the CSRR failed. That being said, it is likely that the small size of Cartersville rendered such a venture economically untenable.

Railroad Car Manufacturing

Bartow County was slowly recovering from the Civil War in the 1870’s. Helping to remedy this issue, many new businesses were founded during the time period, though not many lasted much longer than a few decades. One such business was the Cartersville Car Factory (CCF). Hoping to take advantage of the city’s location on the W&A – and abundant local resources of iron and lumber – one E. N. Gower founded the factory, a railroad car manufactory, in 1871. From the deed records, the business occupied four blocks of downtown Cartersville. It was bounded on the north and south by Church and Main streets, and on the east and west by Tennessee Street and the W&A. The newspapers also feature testimonials from various local figures, including Governor (and, as discussed above, railroad magnate) Joseph Brown.

The services provided by the Cartersville Car Company were many and varied. Advertisements found in archived newspapers of Cartersville detail the various types of rolling stock the company produced: passenger cars, boxcars, and flatcars were all available; woodwork was done in pine, walnut, oak, ash, and poplar; and various decorations, such as sashes, blinds, doors, moldings, brackets, etc. were available on a to-order basis. These services were made possible through a variety of skilled laborers working at the plant – up to 400 people may have been employed at the factory at one time. The equipment used by the company was first-rate for its time: a 30 horse power boiler, a gigantic 40-foot Daniel wood planer, and various other tools such as machine saws and molding machines. As well, the CCF purchased the Bolivar Schofield foundry, which, being located nearby to the plant, was an excellent source of the iron castings necessary for car manufacturing. With such resources, the CCF was capable of producing up to 25 cars per week.

The business proved successful enough to attract competition. In 1880, the Georgia Car Company (GCC) was founded. Its location was just a bit south of the CCF, along the east side of the W&A, between Leake Street and West Avenue (near the current Daily Tribune News). The GCC, like the CCF, would build several workshops to support its endeavors: an erecting building, a paint building, a working building, a machine shop, a blacksmith shop, and several office buildings would all be part of the property, along with a massive dry kiln, built for the cost of $3,000. The GCC was a bit smaller than the CCF, and only employed about 200 people at its peak.

This golden age of railroad car manufacturing in Bartow did not last very long. By 1881, the CCF was advertising in the paper for potential buyers. It is unknown precisely who bought it, but the CCF was closed by 1883. William Noble, president of the GCC, was also looking to get out of the business, and sold the property in November 1883.

Conclusion

Since the Western and Atlantic first came to Bartow in 1843, the fortunes of the county have been reliant upon the railroad. Thanks to its early adoption of the technology, Bartow had a head start in adapting to the changing times of the Industrial Revolution. The ability to directly reach the markets of Atlanta, Chattanooga, and beyond proved an invaluable asset to the economy of the county, chiefly in giving the people an easily-accessible outlet for their iron, lumber, and agricultural products. Such an outlet provided further benefits to the county, especially by attracting yet more railroads to the area, further increasing Bartow County’s prosperity. Over time, though some of these railroads would fail and stop service, those that remain continue to serve as the lynchpin of the Bartow county economy.

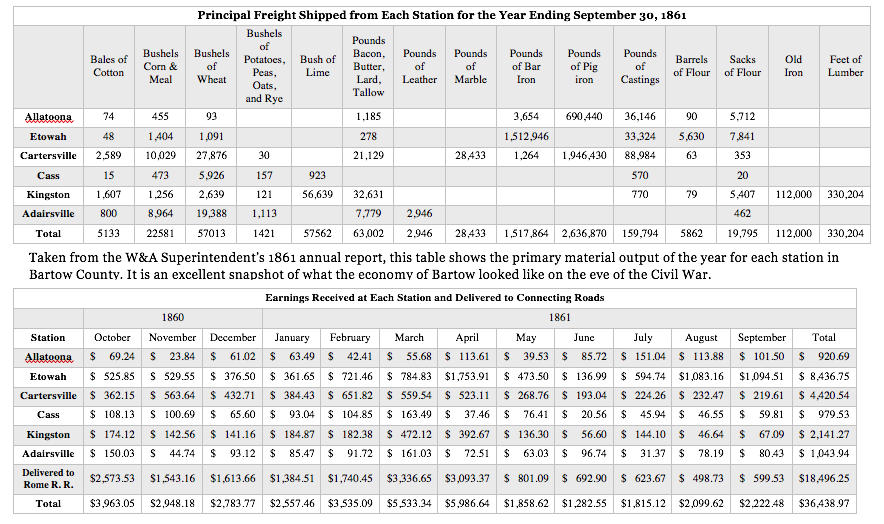

From the same report, this table shows the earnings at each station in Bartow for the same year. This is a concrete indicator of just how much the citizens of Bartow County relied on the Railroad to support their way of life. Of particular note is the precipitous drop-off in revenue between April and May 1861. The Civil War began in April 1861; it is likely that the recruitment of the men of Bartow County into the Confederate Military is the cause of the loss in revenue. This serves as a clear indicator of the immediate effects of the Civil War on Bartow County and its economy.

It is believed that the numbers include both shipping and passenger fees, but the Superintendent’s report did not specify.

Appendix

Historic Railroads of Bartow County

- Western and Atlantic Railroad

Cass Station. The city of Cassville relied heavily upon this stop about two miles to its southwest

- W&A

- Incorporated 1836*

- Owned by the State of Georgia

- Leased by:

- Joseph Brown from 1870-1890

- Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad (NC&St.L) from 1890-1957

- Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) from 1957-1967

- Seaboard Coast Line (SCL) from 1967-1980

- CSX from 1980-Present

- AKA:

- The State Road

- NC&St.L

- L&N

- Runs 138 miles from Atlanta to Chattanooga

-

Allatoona station, with its famed pass in the background

Approximately 47 miles of track in Bartow County

-

- Stops in Bartow, South-North:

-

- Hugo

- Allatoona

- Bartow

- Emerson

- Mile Post 43

- Etowah

- Cartersville

cartersville-depot

- Junta

- ATCO

- Rogers

- Cass Station

-

W&A RR ticket (scrip)

- Bests

- Cave

- Kingston

- Halls

- Linwood

- Clifford

- Adairsville

- Etowah Railroad

- ERR

- Incorporated 1847

- Owned by:

- Mark A. Cooper 1847-1862

- Confederate States of America, 1862-64

The McGuire family residence, for which the infamous McGuire’s curve was named.

- United States Army 1864-66

- Ran 4 miles from Etowah Station, south of Cartersville, to the town of Etowah

- Entirely in Bartow County

- Stops, West-East:

- Etowah Station

- Etowah Township

- Rome Railroad

- R-K

- Incorporated 1839

- Owned by:

- Memphis Branch Railroad & Steamboat Co. 1839-1850

- Rome Railroad Co. (Successor of above) 1850-1894

- NC&St.L – 1894-1943

- AKA:

- Rome-Kingston Railroad

- Memphis Branch Railroad

- Ran 18 miles from Kingston to Rome

The Kingston Station on the W&A. Its destruction by fire in 1911 was one of the final nails in the coffin of the Rome Railroad.

Courtesy: Victor mulinix - Stops in Bartow, East-West:

- Kingston

- Woolley’s

- Eve’s

- Cartersville and Van Wert Railroad

- C&VW

- Incorporated 1866

- Owned by:

- Cherokee Railroad Co. 1871-1873

- Cherokee Iron Company 1879-1888

- Charles Ball 1888-1893

- Eugene Kelly 1893-1902

- Seaboard Air Line 1902-1967

- Seaboard Coast Line 1967-1986

- CSX (Successor to above) 1986-Present

- Leased by:

- East and West Railroad of Alabama 1881-1888

- AKA:

- Cherokee Railroad

- East-West Railroad

- East and West Railroad of Alabama

- Seaboard Air Line

- Ran from Cartersville Station to:

- Taylorsville 1870-1871

- Rockmart 1871-1879

- Cedartown 1879-1883

- Pell City, Alabama 1883-Present

- Stops in Bartow County, East-West:

- Cartersville

- Stilesboro

- Taylorsville

- Iron Belt Railroad[4]

- IB

- Incorporated 1897

- Owned by

- Joseph E. Brown

- John W. Akin

- Ran from Rogers’ station, northeast of Cartersville, to Sugar Hill at its farthest extent

- Entirely in Bartow County

- Stops, South-North:

- Rogers’ Station

- Note: this railroad was dedicated to servicing the mines of the county. As such, its track and its stops would change substantially year by year to reach new ore deposits and to abandon depleted ones. Many of these changes are undocumented.

- Etowah-Cartersville “New Line” Railroad

- ECNL

- Incorporated 1904

- Owned by:

- L&N 1906-1980

- CSX 1980-Present

- Runs from Junta, in the north of Cartersville, to Etowah, Tennessee

- Stops in Bartow County, South-North:

- Junta

- Rydal

Proposed Railroads of Bartow County

These railroad initiatives were, for one reason or another, never brought to fruition. Records of them are still extant in the state legislative archives.

- Alabama and Georgia Railroad

- A&G

- Incorporated February 2, 1850

- Intended to run from an indeterminate point on the Alabama border to Cartersville

- Atlanta and Blue Ridge Railroad

- A&BR

- Incorporated October 17, 1870

- Intended to run “from Cartersville to such point as they may select on the Carolina line, and within the county of Rabun.”

- Lookout Mountain Railroad

- LMRR

- Incorporated October 24, 1870

- Intended to run westwards from Kingston to Dirt Town, Georgia, in Chattooga County

- Despite the name, it would not go anywhere near Lookout Mountain

- North Georgia and Ducktown Railroad

- NG&D

- Incorporated March 4, 1872

- AKA: Iron Valley Railroad

- Intended to run Northeast from Cartersville, to the Tennessee state line, near to the city of Ducktown, Tennessee

- Etowah and Blue Ridge Railroad

- E&BR

- Incorporated September 30, 1880

- Intended to run from Cartersville to Gainesville

- Kingston, Walesca, and Gainesville Railroad[5]

- KW&G

- Incorporated September 30, 1881

- Intended to run eastwards from Kingston, through Walesca and Canton, finally terminating at Gainesville, later given extension to unspecified point on the Savannah River.

- Rome and Decatur Railroad

- R&D

- Incorporated July 30, 1883

- Intended to run from Rome to the Alabama line

- In 1886, given extension to Gainesville, passing through Bartow county

- Gainesville and Western Railroad

- G&W

- Incorporated October 13, 1885

- Intended to run from Gainesville to Cartersville

- Rome and Northeast Railroad

- R&NE

- Incorporated December 20, 1886

- Intended to run from Rome to Gainesville, passing through Bartow

- Cartersville and Gainesville Airline

- C&G

- Incorporated December 24, 1886

- Intended to run from Cartersville to Gainesville

- Later given extension to Augusta

- Salt Springs North and South Railroad

- SSN&S

- Incorporated December 24, 1886

- Intended to run from Cartersville to Salt Springs (now Austell)

- Cartersville, Marysville, and Knoxville Airline

- CM&K

- Incorporated September 29, 1887

- Intended to run northeast from Cartersville, through Gordon, Murray, and Fannin counties, to the Tennessee border

- Fort Payne and Eastern Railroad

- FP&E

- Incorporated August 8, 1889

- Intended to run from Gainesville to the Alabama line, passing through Bartow

- Union Railroad and Transfer Company

- UR&T

- Incorporated September 2, 1889

- Known Bartow County Investors:

- Intended to run from Rome to the North Carolina line, passing through Bartow County

- Fairmount Valley Railroad

- FMV

- Incorporated November 3, 1889

- Intended to run northeast from Cartersville, through Gordon, Murray, and Fannin counties, to the Tennessee border

- Cartersville Street Railroad

- CSR

- Incorporated November 11, 1889

- Intended to run “upon such streets, ways or routes as the Mayor and Council of [Cartersville] may consent to.”

Bibliography

Cunyus, Lucy. 1932. History of Bartow County, Georgia Formerly Cass. Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press

Denney, Kevin S. “Etowah: Boomtown, Ghostown, and Sunken Treasure,” Etowah Valley Historical Society collection (1993)

Hilton, George W. 1991. American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford, Calif: Stanford Univ. Press.

Johnston, James Houstoun. 1932. Western and Atlantic Railroad of the state of Georgia. Atlanta: Stein Print. Co., State Printers

Online Print

Kesler, Thomas L. Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Cartersville District Georgia. Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1950

“The Days They Changed the Gauge” Ties, August, 1966. http://southern.railfan.net/ties/1966/66-8/gauge.html (Accessed December 10, 2017)

Thomas, Henry W. Digest of the Railroad Laws of Georgia. Atlanta: Franklin Printing and Publishing Company, 1895. Accessed December 15, 2017. Google Books.

Vipperman, Carl J. “The ‘Particular Mission’ of Wilson Lumpkin.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 66, no. 3 (1982): 295-316. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.kennesaw.edu/stable/40580931. (Accessed November 19, 2017)

Deeds

Georgia, Bartow County. Deed books. XXX Year – XXX Year. Bartow County Deeds office, City of Cartersville.

Government Documents

Georgia, Bartow County. Charter Book of Businesses. 1898-1906. Etowah Valley Historical Society, City of Cartersville.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. AMENDING CHARTER OF ROME AND DECATUR RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 86. 1886-1887 Reg. Sess. (December 24, 1886). GALILEO. Web. 12 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. AN ACT to authorize the Alabama and Georgia Railroad Company of the State of Alabama to extend their contemplated Railroad…. No. 290. 1849- 1840 Reg. Sess. (February 23, 1850). GALILEO. Web. 12 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. An Act to incorporate the Atlanta & Blue Ridge Railroad Company, granting State aid to the same, and for other purposes therein named. No. 193. 1870-1871 Reg. Sess. (October 17, 1870). GALILEO. Web. 13 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. An Act to incorporate the Lookout Mountain Railroad Company, and to extend the aid of the State to the same, and for other purposes. No. 217. 1870-1871 Reg. Sess. (October 24, 1870). GALILEO. Web. 13 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. An act to incorporate the North Georgia & Ducktown Railroad Company, and for other purposes. No. 238. 1872 Reg. Sess. (August 27, 1872). GALILEO. Web. 11 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. ETOWAH AND BLUE RIDGE RAILROAD INCORPORATED. No. 475. 1881 Reg. Sess. (September 30, 1881). GALILEO. Web. 13 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE CARTERSVILLE AND GAINESVILLE AIRLINE RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 99. 1886-1887 Reg. Sess. (December 24, 1886). GALILEO. Web. 12 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE CARTERSVILLE, MARYSVILLE AND KNOXVILLE AIR-LINE RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 238. 1887 Reg. Sess. (September 29, 1887). GALILEO. Web. 11 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE CARTERSVILLE STREET RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 829. 1889-1890 Reg. Sess. (November 13, 1889). GALILEO. Web. 15 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE FAIRMOUNT VALLEY RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 534. 1889-1890 Reg. Sess. (November 4, 1889). GALILEO. Web. 13 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE FORT PAYNE AND EASTERN RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 191. 1889 Reg. Sess. (August 8, 1889). GALILEO. Web. 13 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE GAINESVILLE AND WESTERN RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 362. 1885 Reg. Sess. (October 13, 1885). GALILEO. Web. 12 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE ROME AND NORTHEAST RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 31. 1887-1888 Reg. Sess. (December 20, 1886). GALILEO. Web. 15 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE SALT SPRINGS, NORTH AND SOUTH RAILROAD COMPANY. No. 68. 1886-1867 Reg. Sess. (December 24, 1886). GALILEO. Web. 12 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. INCORPORATING THE UNION RAILROAD AND TRANSFER COMPANY. No. 240. 1889 Reg. Sess. (September 2, 1889). GALILEO. Web. 12 December 2017.

Georgia (State). Legislature. Assembly. KINGSTON, WALESCA AND GAINESVILLE RAILROAD INCORPORATED. No. 460. 1881 Reg. Sess. (September 30, 1881). GALILEO. Web. 11 December 2017.

Interviews

Brooke, John. 2017. Interview by Giovanni Martino. Etowah Valley Historical Society

Garland, Michael. 2017. Interview by Giovanni Martino. Etowah Valley Historical Society

France, Todd.2018. Manager of Signal CSX Atlanta Division Cartersville

Mulinix, Victor. 2017. Interview by Giovanni Martino. Etowah Valley Historical Society

Posey, Larry. 2017. Interview by Giovanni Martino. Etowah Valley Historical Society

Maps

Cooper, J. F, Western and Atlantic Railroad Company, and F. C Arms. Map of the country embracing the various routes surveyed for the Western & Atlantic Rail Road of Georgia, under the direction of Lieut. Col. S. H. Long, Chief Engineer, U.S. Topographical Bureau M. H. Stansbury, Del. [map]. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688853/. (Accessed November 20, 2017.)

Tennessee Iron and Coal Railroad Company. [Mining Operations, Bartow Georgia]1916.

U.S. Geological Survey. Acworth Quadrangle, Georgia [map]. 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1971.

U.S. Geological Survey. Allatoona Dam Quadrangle, Georgia [map]. 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1971.

U.S. Geological Survey. Cartersville Quadrangle, Georgia [map]. 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1971.

U.S. Geological Survey. Kingston Quadrangle, Georgia [map]. 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1971.

U.S. Geological Survey. Cartersville Sheet, Georgia [map]. 1:125,000. Series unknown. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1939.

Newspaper Articles

“A Great Peach Crop.” The Cartersville News and Courant, August 11, 1904.

“Copy of Rail Removal Plea Reaches Rome.” The Tribune News, November 26, 1942.

“Dirt Broken on A., K. &N. Extension.” The Cartersville News and Courant, October 27 1904.

“Examiner Recommends Abandonment of Railroad.” The Tribune News, March 4, 1943.

“Fifteen Carloads Scrap Metal from Etowah Bridge.” The Tribune News, February 15, 1945.

“Million-Dollar Railroad Bridge Over Etowah River Opened to Traffic Late Tuesday Afternoon.” The Tribune News., November 7, 1944.

“Road is Paralleled.” The Cartersville News and Courant, November 24, 1902.

“Some Facts about Starting a Railroad.” The Cartersville News and Courant, November 3, 1904.

“The State Road and Gen. Gordon.” The Cartersville American, June 1, 1886

‘The W.&A. Railroad: Some Inside Facts Relating to its Financial Management.” The Chattanooga Times, July 6, 1890.

“Who Owns Land Formerly Used by Rome Railroad.” The Tribune News, November 11, 1943.

Online

Bright, David L. “Western & Atlantic”. CSA-Railroads.com. http://www.csa-railroads.com/Western_and_Atlantic.html (Accessed February 1, 2018)

Head, Joe F. “Cartersville’s Railroad Car Manufacturing Age.” EVHSonline.org. https://evhsonline.org/archives/43277 (Accessed January 12, 2018)

Lusk, Staci. “Bartow’s Mining Legacy,” EVHSonline.org. https://evhsonline.org/archives/43808 (Accessed Januard 23, 2018)

Sorey, Steve. “Georgia’s Railroad History and Heritage,” railga.com. https://railga.com/index.html (Accessed January 20, 2018)

US Army Corps of Engineers. “Allatoona Lake.” USACE Mobile District, US Army Corps of Engineers, www.sam.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Recreation/Allatoona-Lake/About/History/ (Accessed February 9, 2018).

[1] This was the first railroad tunnel in the Southern United States

[2] While the origin of the name “Junta” is not certain, it is worth noting that, in Spanish, the word “Junta” carries a similar meaning to the words “meeting” and “joining” in English.

[3] Much of the area formerly occupied by TCI is now covered by Lakepoint Sports Park.

[4] The name of the railroad as shown here – “Iron Belt” – is how one may find it in the Bartow County Charter Book of Businesses. “Ironbelt” is also a common usage.

[5] The name of the modern town of Waleska is indeed spelled with a “k” at the end of the word. However, at the time of this railroad’s proposition, it was spelled with a “c”. “Walesca” is the name the town was incorporated under in 1889.