Bartow’s Mining Legacy

Featuring a Special Tribute to 101 Years of New Riverside Ochre Mining History

Staci Lusk, Intern

Kennesaw State University

Sponsored by: The Etowah Valley Historical Society

August 2, 2016

Supervised by: Joe F. Head

Bartow’s Mining Legacy

Featuring a Special Tribute to 101 Years of New Riverside Ochre History

With the arrival of developments such as the LakePoint Sports Complex and the proposed Avatron Virtual Theme Park in Emerson, one can see that the legacy of Bartow’s local history is being threatened and must be preserved before it is entirely erased. Additionally, other enterprises across the county such as shopping centers, residential subdivisions and industrial parks are also threatening Bartow’s history. Rapid commercial expansion can be witnessed right in our own backyards. While these additions will undoubtedly generate much needed revenue and commerce to the Bartow County area, they also increase the risk of local history being lost or forgotten.

Though the area contains a plethora of historically significant sites and curiosities, one of the most significant aspects of Bartow’s local history is the mining industry. For over 150 years the mining industry has been a rich contributor to shaping Bartow County and making it great. Incidentally, LakePoint Sports Complex and Avatron will be built upon former mining land. Because of this, it is vitally important to document and preserve this important part of history before it is quite literally covered up.

Early Bartow History

The area known today as Bartow County has been continuously occupied for many thousands of years, beginning first with the Paleoindians around 12,000 B.C. During this period, the area abounded with megafauna (large game) as well as smaller game such as white-tailed deer. These early occupants would have subsisted by hunting and gathering, being nomadic rather than living in permanent settlements. The presence of the Paleoindians can be seen in the stone projectile points they have left behind in the archaeological record. Points were commonly flint-knapped using chert or flint, which is available in abundance in Bartow County. The presence of large quartz veins would have also provided material for tools and weaponry.

The Paleoindians gave way to the Archaic Period and lasted roughly from 8,000-1,000 B.C. During this time, there is an increased focus on social organization and increased sedentism. Bartow County, with its forests and ample water sources would have been an ideal area for settlement. By 1,000 B.C. permanent settlements were beginning to appear in the area.

The Woodland Indian Period (1,000 B.C.-1,000 A.D.) gave rise to new technologies such as the bow and arrow as well as increased ceremonial activity. With the increase in ceremonial activity, we see an increase in material goods and art. Ochre was a popular material the Native Americans used to add color to pottery and clothing, as well as for body ornamentation. Effigies, such as those uncovered at the Etowah Mounds, were carved from regionally sourced marble and may represent ancestor worship. Pipes, bowls, and small figurines would have been carved from soapstone.

One of the more important Woodland sites is the Leake Site, in Cartersville. The village was occupied from 300 B.C. to 600 A.D. and is located in close proximity to the Etowah River. This would have provided not only drinking water, but also fish and mussels for consumption.

Archaeologists have found the remains of three earthen mounds as well as evidence of trade with other Native Americans as far as the Midwestern United States. Copper has been found that potentially came from Michigan. Flint from the Ohio Valley has also been found on site, indicating a vast trade network. Jewelry, such as necklaces, was made using shells found in the Etowah River; these may have been used in trade. The Leake Site was abandoned around 650 A.D. for unknown reasons. Several other sites of importance are located adjacent to the Leake Site and help solidify the ancient human presence of the area. These include sites on Ladds Mountain such as the Shaw Mound, Indian Fort, and Ladds Cave. Undoubtedly, Bartow County’s rich natural resources were a contributing factor to the settlement of these complexes. Unfortunately, the sites were dismantled in the first half of the 20th century for agricultural use and road construction materials.

Perhaps the most prolific period of Native American occupation was the Mississippian Period that spanned from 1,000-1,540 A.D. Extensive assemblages of stone tools and ceramics have been recovered from archaeologists that attest to the increased social and political organization of this time. This period also gave rise to the great Mound Builder societies, as we can see at the Etowah Indian Mounds.

Beginning around 1,000 A.D. the Etowah Indian Mounds were occupied by several thousand residents and boasted six earthen burial mounds that spanned fifty-four acres. Like the Leake Site, the Etowah Indian Mounds settlement is located on the Etowah River, which would have provided excellent resources for the tribe. Excavations have uncovered the presence of a sophisticated society that put much emphasis on ceremony. Many of the artifacts that point to this conclusion would have been made from natural resources obtained from the local area such as flint, graphite, ochre, and shell, as well as being obtained through extensive trade networks. Though the site seemed to thrive, it was suddenly abandoned in 1200 A.D. and then resettled fifty years later.

According to Jim Langford, Hernando de Soto and his Spanish troops came through the area in August of 1540 and spent a few days at the Etowah Indian Mounds as they waited for the Etowah River to go down, following substantial flooding. By the time the de Soto expedition came through, the Mississippian culture was in steep decline. This was only made worse by the presence of Europeans who brought new pathogens with them that caused widespread disease and death to all Native Americans that they encountered. It is estimated that the Native American population decreased by 95% between 1500 and 1700. The fall of the Mississippian culture ushered in the post-Contact Period of European settlers. The influx of Europeans continued through the 19th century.

By 1829, north Georgia was flooded with prospectors hoping to strike it rich with gold. Based on maps from 1831, the Cherokee Nation stretched across most of northwest Georgia as well as parts of Alabama, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Though found mostly around the Dahlonega and Villa Rica area, many prospectors were drawn into Bartow County as they followed the trail to search for the elusive gold.

The Georgia Gold Rush saw a frenzy the likes of which had probably never been seen before. In 1830, the Georgia Assembly passed legislation that allowed for land surveying, despite the Cherokee ownership, and divided the land into “sections, districts, and land lots” and authorized a lottery to distribute the land to white settlers. Unfortunately for those hopeful men, gold was never found in abundance in Cass or anywhere else in Georgia. In 1832 the entire area of Cherokee County was divided into nine counties, Bartow being one of them.

At the time, Bartow was referred to as Cass County, with the county seat being at Cassville. It was named for Lewis Cass, Secretary of War under Andrew Jackson, though the name was changed to Bartow County in 1861 as he fell out of favor with southerners because of his Union sympathies. Bartow is named for Colonel Francis S. Bartow, a Savannah resident and staunch supporter of the Confederacy.

Francis Bartow was a lawyer, politician, and University of Georgia graduate who resided in Savannah prior to the Civil War. He spent some time at Yale University studying the law before moving back to Georgia where he served two terms in the House of Representatives and one term

in the Senate. When the Civil War began, Bartow was the captain of the Oglethorpe Light Infantry and participated in the siege of Fort Pulaski. The same year, he was elected to the Confederate Congress. He quickly resigned from this honor in order to lead a militia to Virginia. He was shot and killed at the Battle of Bull Run. It is rumored that, as he lay dying, his last words were, “They have killed me boys, but never give up the field.” It is little wonder that the residents of Bartow County chose to name their home after such a romantic figure.

Gold was found in quantity to sustain ongoing mining operations in other parts of Georgia but not in Bartow County; despite this, the miners did uncover a vast wealth of other resources such as iron, barite, and ochre. These three ores would become the most heavily mined resources in the area. Known as the Cartersville Mining District, people began to flow into the area to mine these secondary materials. The district is one of the oldest, continuously mined districts in the U.S. In the early days of mining, dozens of operations cropped up to take advantage of these resources. See Appendix for list of mining operations.

Iron Mining in Bartow County

Iron gives north Georgia its characteristically red clay and occurs in abundance throughout the state, including the Cartersville Mining District. It is likely that Native Americans mined iron by hand for centuries before white settlers came into the area, though there is no written record of this. Mining began in earnest in the 1840’s, though there is record of iron mining as early as 1837. Records show that Jesse Lamberth sold the Etowah Works to Alexander Stroup in 1837. A few months later Alexander signed the property over to his father, Jacob. Alexander’s brother, Moses, also joined the venture. The first iron furnace was built on the site and called the Etowah Bloomary and was replaced in 1841 with the Etowah Bloomary Forge Number 2.

The bloomary was a precursor to the blast furnaces that are seen throughout Bartow, including Cooper’s Furnace at the Allatoona Day Use area. A bloomary was typically made from clay or stone and was capable of smelting iron, yet it wasn’t until the larger blast furnaces came into use that pig iron was created. Pig iron was so named because of the manner in which the smelted ore exited the furnace into a long dirt trench. It formed a main trunk bar several feet long with finger like comb attachments, which resembled suckling piglets.

The Stroups were no strangers to the mining industry. Prior to opening up shop in Cartersville, Jacob owned and operated an iron making business as early as 1815 in South Carolina. He founded the King’s Mountain Iron Company, followed by Cherokee Iron Works in 1826. He sold this business and followed the gold rush to north Georgia where he set up Stroup Iron Works in 1831. The Cartersville business was sold to Mark Anthony Cooper in 1843, though Moses stayed on to help run it.

Mark Anthony Cooper

Mark Anthony Cooper moved to Bartow County in 1842 in order to partner with Moses Stroup and begin a mining business. Cooper was a major advocate and influence in getting the railroad constructed to run through Bartow. Prior to becoming involved in mining, Cooper was elected state representative in 1833, then to Congress in 1838. After losing re-election, he moved to Bartow and bought the Etowah Works from the Stroups.

Allatoona Furnace

In 1849 Cooper established the Etowah Rolling Mill near his Allatoona Furnace (which can still be seen today). The mill was water driven and it is recorded that in 1856 the rolling mill produced 900 tons of iron. Though impressive, this was not Cooper’s most ambitious endeavor. He and a partner founded the town of Etowah in 1845 nearby that boasted a population of around 800 people at its height.

The town of Etowah was located about a mile from where the Allatoona Furnace is today; the ruins of the town were flooded in 1950 with the building of the Allatoona Dam. In 1858 Cooper built the Etowah Railroad, connecting his rolling mill to the Western and Atlantic Railroad, approximately two miles away. This made it much easier to transport the pig iron he was producing, as well as making it easier to receive shipments. Also part of the town was the Etowah Manufacturing and Mining Company that produced iron for several railroads.

By 1861, the American Civil War had begun and the rolling mill of Etowah would become a target of General Sherman. In May 1864 Union forces burned the entire village, leaving only the stone furnaces and building foundations. Whether luck or foresight, Cooper sold the mills to the Confederate government in 1863, prior to Sherman’s famous March. Unfortunately, he received payment for this through $400,000 in Confederate bonds, which were not worth the paper they were printed on following the war. Like most others in the area, the Civil War took a heavy toll on Cooper.

The Stroups and Cooper were pioneers of the Bartow iron mining industry, though dozens of others had a hand in shaping the area as well. Many of the early mining operations took place on private land, while others were owned and operated by companies. Iron ore deposits were located on hundreds of acres across the county, some of which provided a substantial amount, while others yielded on small quantities of the ore. The exact amounts that the banks yielded are unknown, as detailed records were not always kept. S.W. McCallie, Georgia state geologist, estimated that in 1900 there were still 75-80 train carloads being shipped out daily from Cartersville. This is after six decades of iron mining in the area.

Several of these iron-mining sites were located on Colonel C.M. Jones’s property that stretched across hundreds of acres on Pumpkinvine Creek in the 4th District. The banks were mined extensively from 1876 until about the turn of the 20th century. Most of the mining was done through large open cut pits. Because of the lack of documentation, the output of the property can only be estimated in the range of “many hundreds of tons”, according to McCallie.

Another prosperous bank was the Guyton Ore Bank, located in Cartersville. It was mined from the 1860’s-1873, then bought by Governor Joseph E. Brown. Brown constructed a branch railroad in order to ship the iron out of the mines as well as 3 log washers on sight. Mining ceased in 1893 with the mines being reopened in 1900 by the Southern Mining Company.

Other notable banks include the Lowry Ore Bank that is located just north of the Guyton Ore Bank, the Bishop Ore Bank, Burford Ore Bank, and the Wild Cat Ore Bank that is located in close proximity to the Sugar Hill Bank. The Sugar Hill Ore Banks were the most productive in Georgia, producing between 25-60 carloads of iron each day between 1898-1900. The banks are located near Pine Log.

Early iron mining was done with pick axes and shovels, then with open cuts or open pits and relied on the many stone blast furnaces in the area to process the iron. This all changed in 1869 with the introduction of the Bessemer Convertor, which changed the industry drastically. The Bessemer could efficiently remove the impurities from iron ore, and allow for the mass production of steel. Steel is a much more durable material and began to replace the use of iron in many industries, such as the railroad. The last mining of iron ore in Bartow County took place in the early 1960’s by the Hodge family near the Wax community near Taylorsville.

Dobbins Mining Cut

Barite Mining in the Cartersville Mining District

According to the 1920 Georgia Geological Survey, the barite mines in the Cartersville Mining District are the most productive in the United States. Currently, there are only two active barite mines in the United States, one of which is run by New Riverside Ochre in Bartow. The 1970 Geological Survey Report states that there are over “two thousand specific industrial applications” for barite. Some of these applications include being widely used in drilling, as well as for pigment. It can be used as filler for paper or other materials such as rubber. It is also the main component of barium, which can be used in a variety of different ways including x-ray shielding, glazes, “ferrite magnets, barium titanate, barium sulfate, miscellaneous barium chemicals and various types of glass including television picture tubes, reflective glass beads and other specialty scientific, optical and art glasses.”

Barite has been produced for over one hundred years in the Cartersville District, though it did not begin in earnest until the First World War. Between 1914 and 1916, the Cartersville District was the top producer of barite in the country. In 1917 more than half of the barite mined in the U.S. was done so in Bartow County. One of the most lucrative barite mines in the District was the Big Tom Mine about a mile southwest of Emerson.

The Big Tom Mine was the first to be mined in the District in the 1880’s. During this time the mine was owned by the Pyrolusite Manganese Mining Company. In 1915, J.E. and W.C. Satterfield purchased the property and ran it under the name Big Tom Barytes Company. In 1919 the property was leased to J.A. Morgan and W.S. Peeples. The mine was operated only a few months until work was suspended. It lay idle until New Riverside Ochre reopened it in 1998. The mine was then operated for seven years. It was reclaimed during the construction of the Red Top Mountain Connector and is now covered by Emerson Elementary School.

Another high-yielding mine is the DuPont mine, located relatively close to the Big Tom mine. Owned by the Thompson-Weinman Company in 1917, it was purchased by the E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Company in 1918. His property was eventually acquired by NRO and was mined by NRO during the period 1996-2004. The mined area was reclaimed and now is covered by the Red Top Mountain Connector.

Manganese Mining

According to the 1919 Geological Survey Bulletin, the manganese ore deposits of the Cartersville District exist in a narrow belt that is about 18 miles long and 1 to 2 miles wide in southeastern Bartow. Manganese deposits are typically found from the height of the Etowah River, to 400 feet above. Deposits of manganese typically occur in conjunction with ochre, barite, and limonite.

Manganese was mined in the Cartersville District following the mining of iron ore; much of the iron mined in the region had a fair amount of manganese mixed in with it, naturally. The first recorded site mined for manganese was about two miles east of Cartersville. The first shipments were in 1866 from the Dobbins Mine. This was the first manganese mine in the state of Georgia. The majority of manganese mined in Georgia has taken place in the Cartersville District. According to the 1919 Geological Survey Bulletin, total production at the time totaled 100,000 tons. The largest producers were the Bartow Mining and Manufacturing Company, the Etowah Development Company, and the Georgia Iron and Coal Company.

The Role of Railroads in the Mining Industry

With the mining industry beginning to boom in Bartow County, a more efficient means of transporting materials was needed, and this need was met by the railroad. Founded in 1836, the Western and Atlantic Railroad connected Atlanta to Chattanooga, with stops in Bartow County. The railroad gained notoriety during the Civil War with the Great Locomotive Chase that took place in 1862. Before that, however, it was an integral part of industry in the area.

Mark Anthony Cooper, the founder of the town of Etowah, was a major investor and supporter of the W & A Railroad. Later, he would build his own railroad. Along with Jacob Stroup and Leroy Wiley, Cooper chartered the railroad in 1847, though it would not be built until 1858. The Etowah Railroad was only four miles long, and connected to the W & A near Emerson at Etowah Station. Originally, the railroad was to go as far north as Dahlonega, but insufficient funding made this impossible. The Etowah railroad ran until 1864 when Union troops destroyed Cooper’s iron works, along with much of the other industry in the county.

Following the Civil War, several railroads surfaced to support the local mining industry. Among them were the Cartersville-Van Wert, Iron Belt Railroad, and the Cherokee Railroad. Additionally, two railroad car manufacturing companies were built in downtown Cartersville, supplying ore cars to the mining industry.

The Cartersville-Van Wert Railroad was chartered in 1866 to stretch 45 miles to connect the W & A to the Selma, Rome, and Dalton Railroad. However, financial troubles ensued and in 1870 only 14 miles of track had been laid between Cartersville and Taylorsville. The name was changed to the Cherokee Railroad later in the same year.

The Cherokee Railroad was the first railroad in the south to utilize narrow-gauge track. Despite this innovation, the railroad was doomed to follow the same path as the Cartersville-Van Wert and foreclosed in 1878. In 1879 it was sold to the Cherokee Iron Company, then again to the East and West Railroad in 1886. The Iron Belt Railroad, though a smaller service, operated in Sugar Hill, hauling ore to the W&A Line at Roger’s Station.

Construction first began in the 1880’s and had financial backing from investors that included former governor Joseph E. Brown. Brown had many mining investments in the area. The first section that was laid connected Roger’s Station to the Guyton mine, 3 miles away. As the line extended, more mines were opened, as ease of transport increased. In 1898 the construction of the railroad was complete, and stretched from Roger’s Station to Sugar Hill. Extensive brown ore mining occurred at Sugar Hill under the ownership of John Akin and L.S. Munford.

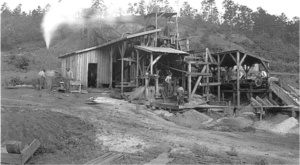

Satterfield Barite Washer, c 1920

In 1902, Joel Hurt, president of the Southern Mining Company (later named the Georgia Iron and Coal Company), purchased Sugar Hill. Hurt utilized the unconscionable system of convict leasing, and was able to lease many convicts that doubtlessly had to endure very harsh conditions while working the many mines owned by Hurt in the area. In 1903, common carrier service ended on the railroad, though there are records showing the line and the mines were still in service in 1919.

Ochre Mining in the Cartersville District

Ochre has been mined in Bartow County since the late 1870’s, according to records. At one time there were several ochre companies in operation, though today there is only New Riverside Ochre.

Paga Mine 1917

At one time, Scotland was a great consumer of the ochre produced in the Cartersville District because of the popularity of linoleum. According to the New Riverside Ochre website, ochre is used as a pigment in all cementaceous products, grout, stucco, as well as a pigment for plastic and rubber products. During the Second World War, ochre was used to produce camouflage coloring for military equipment.

Riverside Ochre Washer Early 20th Century

The first recorded occurrence of ochre mining in the Cartersville District was in 1877 by E.H. Woodward. According to the 1906 Geological Survey, the crude product was hauled into town using wagons and prepared for market. The Survey lists Mr. A.P. Silva as an ochre miner in 1878, with M.F. Pritchett purchasing the interests of both Woodward and Silva. This property was sold in 1890 to the Georgia Peruvian Ocher Company and the first shipment to Europe took place in 1891.

E.P. Earle, a mineral broker of New York City (and future shareholder of the Empire State Building), became interested in this property as, while on a train passing through, he spotted what he recognized as ochre in the banks of the hills. He had the conductor stop the train and got off to collect samples. He had years of experience with ochre, specifically that produced in Peru. Recognizing the superior quality of this Georgian ochre, he began setting up business in Bartow County. Earle was joined by J.C. Oram. Oram would revolutionize the ochre industry by developing an alternative drying method that involved using large vats placed in the ground. Within a few short years the ochre industry would boom in Bartow County.

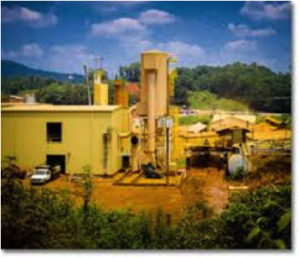

New Riverside Ochre Washer

Following the development of the Georgia Peruvian Company, many more ochre businesses were begun. In 1890 Etowah Ochre and Talc opened, run by John A. Dobbs, then Cherokee Ochre and Barytes Company set up shop near the Western and Atlantic Depot in Cartersville. This was followed by the Blue Ridge Ochre Company in 1899 and the American Ochre Company in 1902. Riverside Ochre was begun in 1905 by W.C. Satterfield and later rebuilt under the name of New Riverside Ochre in 1915 after a fire burned through the original structure. For a more complete list of ochre mining companies in the Cartersville District, please refer to the Appendix.

New Riverside Ochre: Last Man Standing

One cannot speak of ochre mining in the Cartersville District without New Riverside Ochre (NRO) coming to mind. This is because they have prospered for more than 110 years and have persevered while all the other ochre mining operations shut their doors or were absorbed by NRO. They are the last man standing in the ochre mining industry; indeed, they are the last remaining ochre miners in the United States.

The Satterfields began their mining venture in 1890 with Satterfield and Renfroe Mining Company. This was followed by Riverside Ochre in 1905, with New Riverside Ochre being incorporated in1915. Extensive ochre exploration began in the 1920’s as well as barite mining. In 1933 Chemical Products Corporation was established.

Chemical Products Corporation began producing barium products that were used in television sets and, during World War II, barium nitrate used to make incendiary bombs and tracer bullets. Today, CPC is a trusted producer and supplier of chemicals used in the pulp and paper industry, “porcelain enamel frits, glazes, ferrite magnets, barium titanate, barium sulfate, miscellaneous barium chemicals and various types of glass including television picture tubes, reflective glass beads and other specialty scientific, optical and art glasses”, according to the CPC website. Chemical Products Corporation also has a Sulfur Division that produces specialty sulfur compounds.

New Riverside Ochre

Early in the 20th century the first iron oxide standard was developed at New Riverside Ochre. In the 1970’s plant expansion allows for production blending to minimize quality variations. By the 1980’s the last iron oxide standard was developed with the use of spectrophotometer control. In the first decade of the 21st century, NRO achieved an ISO certification. This International Standard is a tool to ensure “quality, safety and efficiency” and is given to companies that meet the necessary requirements.

For a century New Riverside Ochre has been both a local and international staple in the mineral resource business. Where dozens of other mining companies have closed their doors, NRO continues to go strong. When asked what could be attributed to NRO’s lasting success, Vice President of Operations, Stan Bearden, had this to say:

“I would suggest the foremost reason NRO is the “last standing” is due to the ownership/management. The company, from the beginning has been privately owned and managed by “hands on” of a family member. Members of the fifth generation are now active in the family business. “

Mr. Bearden went on to say of NRO:

“Management has always demonstrated commitment to the community and made decisions based upon long term objectives of what is best for its employees, our community, and the environment. Another important factor in the success of NRO is the first to institute high quality wet separation of the natural iron oxide (ochre) from impurities; and the first to establish standards of product quality. These measures resulted in NRO successfully gaining the confidence of well-established customers, including, but not limited to DuPont, Pfizer, 3M, and the US Government, and many others which are now among the leading colored pigment producers in the U.S. NRO sells directly to the end user but a large percentage of products are purchased by distributors located throughout the U.S. From the earliest years of operation, NRO has been regarded as a reliable and valuable supplier to its customers.”

With such a prolific history in Bartow County, it seems clear that NRO will continue to be a staple in the area, enriching the community around them through both their business dealings and community involvement.

Candid Interview with Jim Dellinger

Today, I think there is no better voice of authority or expert on the mining history of Bartow County than Mr. Jim Dellinger, owner of New Riverside Ochre. On March 9, 2016 I had the distinct honor and pleasure of sitting down with Mr. Dellinger, along with Stan Bearden (Vice President of Operations at NRO) and Joe Head (Vice President of EVHS).

We spent the better part of an hour sitting around the conference table, hearing Mr. Dellinger discuss his family’s role in the mining history of Bartow County, as well as the future of the venture in the area. From this candid interview, it was easy to ascertain that Mr. Dellinger’s family has had a great impact on Bartow County.

Mr. Dellinger’s ancestors on his mother’s side are one of the pioneering families of the mining industry in Bartow County. George W. Satterfield, Mr. Dellinger’s great grandpa, moved into the area from South Carolina and went into the mercantile business. His original business was located in the Callan Building in downtown Cartersville, (Main and South Railroad Street adjacent to the Western and Atlantic Railroad) where the Swheat Market is currently located. Realizing the opportunity to delve into the natural resources business, George began buying up mineral properties around Bartow County with the intention of mining, specifically for ochre. It didn’t take long to find what he was looking for and his vision was brought to fruition; in 1905 Riverside Ochre was developed. Will Satterfield and his wife along with John E. Satterfield were shareholders. In 1915 a fire destroyed the original building and so it had to be rebuilt. The reconstructed building was called New Riverside Ochre.

In 1920, Mr. Dellinger’s mother, granddaughter of George W. Satterfield and only child of William C. Satterfield, boarded a train to Oklahoma to go visit a friend that had moved west. None other than her future husband (Ray Dellinger) came to fetch her from the train station and lo and behold the two fell deeply in love. The pair created quite a stir back in the small town of Cartersville when, two weeks later, they married! Mr. Dellinger’s father came back to Georgia to get involved in the Satterfield’s mining operations.

New Riverside Ochre produced ores that were used to color linoleum, referred to as “battleship brown”. While large quantities were being shipped to Scotland, the largest customer of ore at that time was Armstrong Linoleum of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. During World War II ochre was being mixed with black pigment to develop camouflage coloring and used to tint equipment for the military. According to Mr. Dellinger, there are only two competitors of the mortar color produced by ochre, one of which uses synthetic iron oxide to digest steel in acid for different colors.

Mr. Dellinger spoke of Chemical Products Corporation and it was developed as an affiliate industry of New Riverside Ochre. Chemical Products produces barium sulfate that is used to add luster to television glass. During World War II they manufactured barium nitrate that is used to produce tracer bullets and incendiary bombs. Chemical Products was so important to the war effort that a military Major was stationed here all during the war. At one point, Shell Oil was a main customer of Chemical Products.

Mr. Dellinger stated that New Riverside Ochre was the last major mining operation in the area. Though there have been over 100 mining companies in the county, they have either closed their doors or the Dellinger Group has absorbed them. Among these companies are the Blue Ridge Mining Company, Cherokee Ochre and Barytes, American Ochre, Etowah Manganese and Iron, Etowah Ochre (Mr. Dellinger described this one as NRO’s “ace in the hole), Georgia Standard Ochre, Georgia Peruvian Mining Company, and Munford Mining.

Mr. Dellinger hints that most NRO mines are not visible to passersby, with sites still in existence throughout the country. Where the new LakePoint Sports Complex is located was once the site of graphite mining by American Graphite, as was the location of the current First Baptist Emerson. The first barite mine in Georgia was located where Emerson Elementary School currently stands. The school sits on what was formerly the Big Tom Mine. There are two former mines located on the north side of Main Street in Cartersville that were mined for ten years. One of these is the Lowe Mine that sits on land that was partially owned by Sam Jones’s family. Perhaps the most visible site is where the new Kroger is being built. The land was mined extensively for ochre by NRO and also contained a dynamite shack. It is said that the Knight family housed dynamite inside of a little shack on the land prior to World War II. The area that the Cherokee Place Shopping Center is currently located is also former mining land.

With all of the mining that took place in the 19th century into the 20th century, it would seem that the finite resources would be running out. When posed with this thought, Mr. Dellinger said that there should be between 50-75 years worth of ochre left to mine by NRO, depending on the extraction method. There is also the possibility that more ochre will be discovered.

With a century of history in Bartow County, NRO is deeply embedded in the community, and looks for ways to give back. The Dellinger Scholarship Foundation has been helping to support local students for almost forty years. Mr. Dellinger is also on the local hospital board, a member of the Chamber of Commerce, and makes yearly contributions to the community. Mr. Dellinger also gave 111 acres for the development of Dellinger Park that provides a lovely area for the local community to seek recreation. Regardless of how long the mineral resources will last, it is clear that under the tutelage of Mr. Jim Dellinger, New Riverside Ochre has earned a lasting spot in Bartow County history.

Conclusion

With land being developed at a quick pace in Bartow County for establishments such as LakePointe Sports Centers and the proposed Avatron Entertainment Complex, much of Bartow’s early history is at risk of being lost forever. With over 150 years in Bartow County, the mining industry history is at particular risk for being covered up with new developments. From the 1830’s mining has been an important aspect of Bartow County, which deserves to be preserved.

It was the fleeting pursuit of gold that drew prospectors into the area, but it was the presence of Bartow’s rich minerals such as iron, ochre, manganese, and barite that drove people to settle here. With the mining industry came the railroads, manufacturing plants, and hundreds of jobs. Though the vast majority of mining companies were developed in the first 30 years of the 20th century, they created a lasting legacy that is still very much alive in Bartow, and particularly with New Riverside Ochre.

Acknowledgments

This paper would not have been possible without the enthusiastic help of individuals who are passionate about history and, in particular, the mining history of Bartow County. I would very much like to thank Rebecca Melsheimer and Jose Santamaria of the Tellus Museum for kindly allowing me to take over the library and avail myself of its resources. Thanks must also be given to Jake Gresham, a fellow internist, for help with maps, photos, and deed research.

For his support and patience, I am grateful to Joe Head, Vice President of EVHS. His enthusiasm for the subject is contagious and is a wonderful motivator. A special thanks must be given to Mr. Jim Dellinger for setting aside time out of his busy schedule to meet and speak with me about his family history and the mining history of Bartow. His interview provided a perspective into the industry that I otherwise would not have had the opportunity to see. Special thanks must also be given to Stanley Bearden, Vice President of Operations at New Riverside Ochre, for his willingness to provide information concerning NRO and other aspects of the mining industry, proofreading my terrible rough drafts, and setting aside an office for me at NRO. I am also appreciative of Mr. Jim Langford, Native American voice of authority and Executive Director of the Georgia Meth Project, for taking the time to provide a quote for this paper.

Finally, I think it is prudent to acknowledge those early pioneers that came into Bartow County chasing a dream, and decided to make it their home. Without courageous men and women willing to take step into the unknown and take risks, history would be dull indeed.

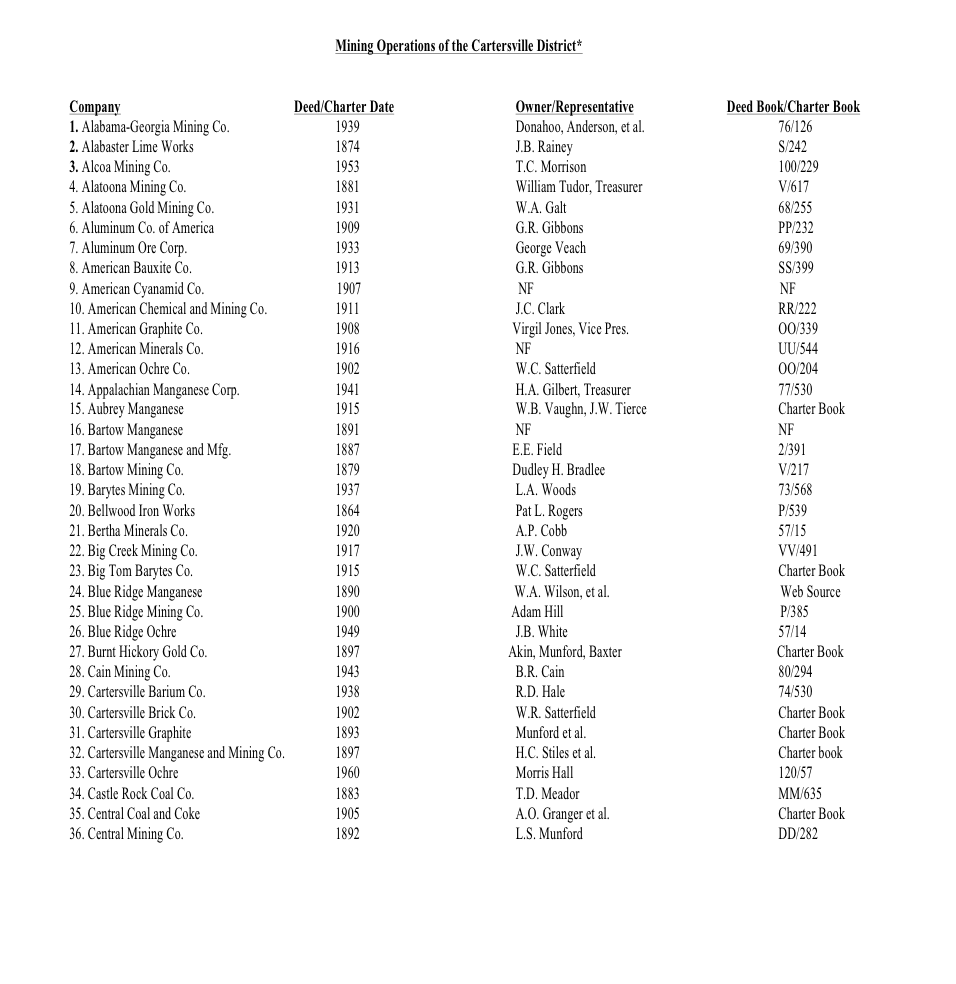

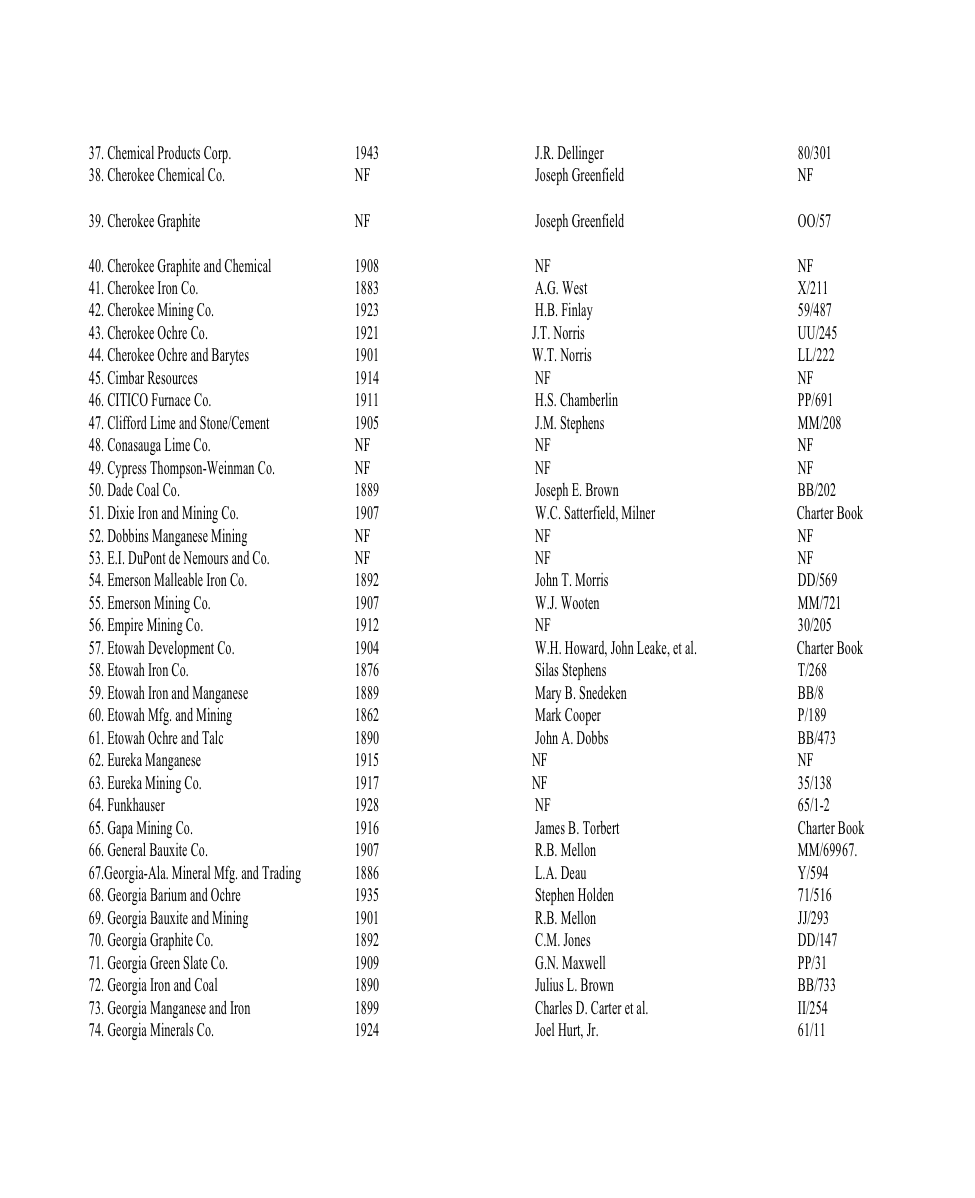

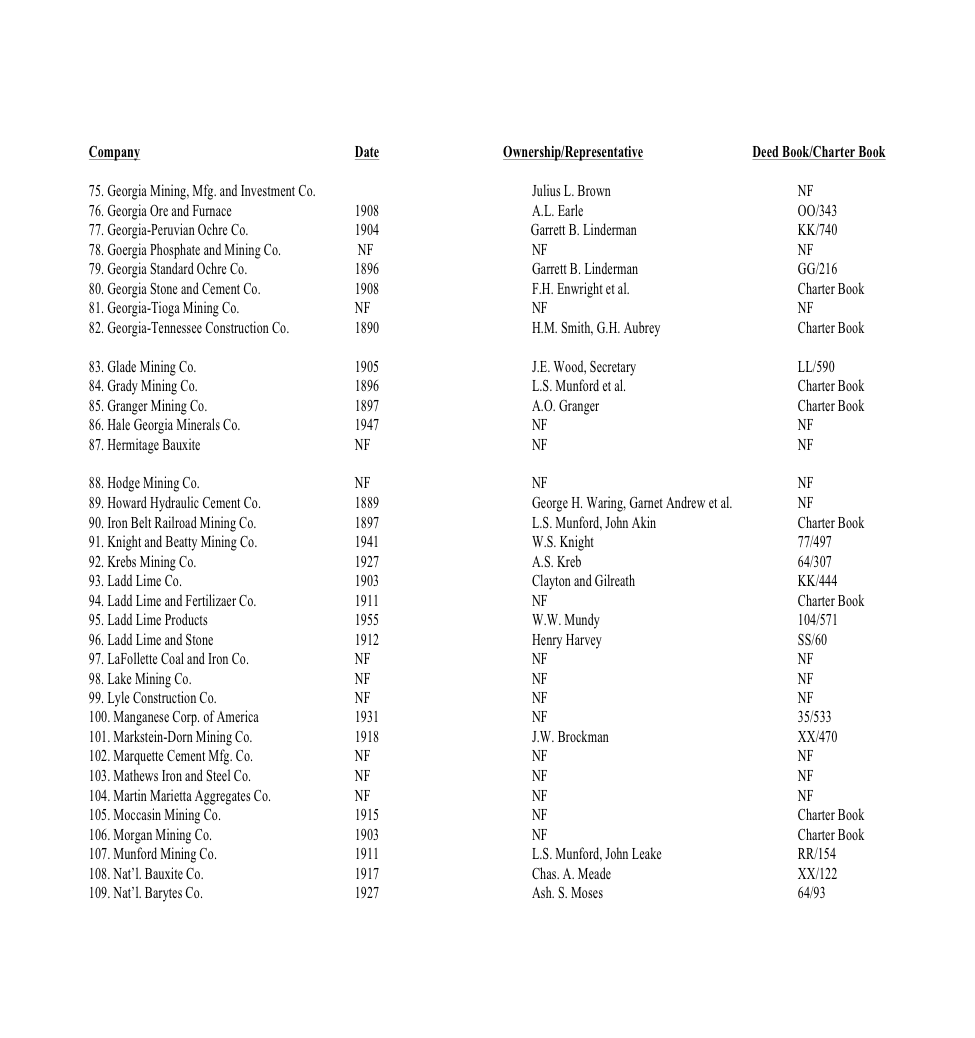

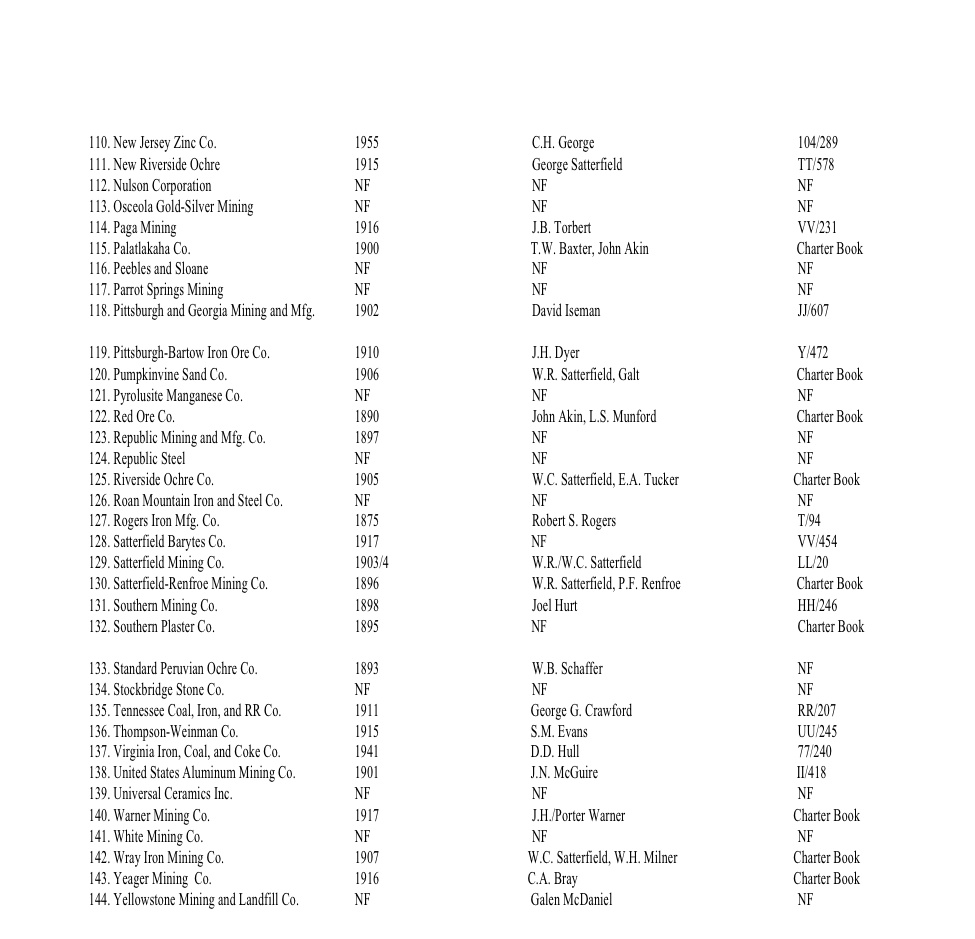

Provided below is a list of registered/recorded mining operations that operated in Bartow County between 1864-today. Approximately 36 of the 144 companies, or 25%, were officially established and recorded prior to 1900. These early companies helped to pave the way for further resource exploration and extraction that occurred throughout the 20th century and continues today with New Riverside Ochre.

Appendix

*Disclaimer: This inventory is compiled to list all mining companies that once operated in Bartow County; however, it should not be considered a conclusive body. Some companies may be duplicated as a result of mergers, family names, or multiple operations. Record keeping and different spellings in the deed records could also be a contributing factor. According to an early 20th century Geological Survey, there once were 300 mining operations in Bartow County. This number likely includes small family operations and informal mining sites.

Key:

NF= Not Found

Charter Book= County ledger of business charters; located in the Etowah Valley Historical Society office

Deed Book= Located in the Bartow County Courthouse Records Room

For further reading:

- Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Cartersville District Georgia, 1950, Thomas J. Kessler

- Minerals of Georgia: Their Properties and Occurrences, 1978, Robert Cook

- http://www.visitcartersvillega.org/About/History/Native-Americans-at-Etowah.aspx

- http://www.bartowdig.com

- http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/histcountymaps/bartowhistmaps.htm

- http://roadsidegeorgia.com/county/bartow.html

- http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/bartow-county

- http://www.aboutnorthgeorgia.com/ang/Western_and_Atlantic_Railroad

- http://railga.com/ironbelt.html

- Report on the Barytes Deposits of Georgia, 1920, S.W. McCallie

- Report on the Manganese Deposits of Georgia, 1919, S.W. McCallie

- org

- com

- Cpc-us.com

- Leake Mounds Site, Scot Keith, Article EVHS 2016

- Cartersville’s Railroad Manufacturing Era, Joe Head, Article EVHS 2016

- History of Bartow County, Formerly Cass, 1933 Lucy Cunyus