The Legend of Chain Gang Hill

A childhood memory re-ignites interest in Bartow’s forgotten Chain Gang Camp

By: Joe F. Head

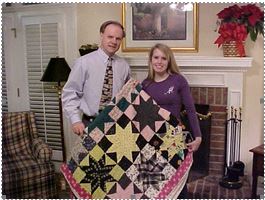

Often family stories and legends fascinate children about the “old days.” They are spellbound with stories about ghosts, myths and fairy tales. One such family story kindled keen interest in my daughter, Meredith, about a hand made quilt and her dad when he was a 5-year old eyewitness to the day Chain Gang Hill burned. The story of the fire that destroyed the old work camp also inspired her to ask other more responsible questions about her grandparents and why Chain Gang existed.

Oral history and a few blurred clippings from community newspapers give scant evidence of a rapidly fading chapter of Bartow County. Georgia’s prison farms and Chain Gangs operated at frequently in Bartow from the 1870’s to the early 1940’s. Only brief local records exist which remain as a legacy to a forgotten time. However, southern folk lore and the entertainment industry have immortalized the chain gang with movies such as, “Cool Hand Luke”, starring Paul Newman, “Oh Brother Where Art Thou”, starring George Clooney, and songs like, “I’ve Been Work’n on the Chain Gang” by Sam Cooke.

The origin of chain gangs can be traced to various forms of slavery in almost every culture. The slave industry thrived in North America for almost two hundred years before it was extinguished by the Civil War. Men and women were captured from native lands, chained and shipped for sale to wealthy individuals in the new world. They were put in irons and sold off slave ships in chains to a life of bondage and hard labor.

However, its use as a penal system in the US was first introduced in Philadelphia following the Revolutionary War. One end of a chain was attached to a cannon ball or wagon wheel and the other was shackled to a prisoner’s ankle. The prisoner was staked out on the town square for public viewing or stationed to a task of hard labor. In fact, early Georgia was founded as a penal colony for criminal debtors and chains were present even in those days.

Plantation masters used chains as a means to confine and transport slaves. Following the Civil War, the southern prison system was left in shambles. As order was restored, criminals were leased to work in the fields, mines, railroads and on public projects. Former Governor, Joseph Brown leased over 300 prisoners for 8 cents each a day to rebuild the W&ARR. The convict lease system was so successful that the need for penitentiaries was almost non-existent.

Prior to 1900, the dilemma of operating tax supported state prisons was solved by transforming state prisons into leased chain gang labor for private profit. Flexible chains permitted mobility for hard labor. Lodging, meals, confinement and security rested with the lessee. This proved to be a powerful force to deal with post Civil War issues and rising labor costs. In 1908, Georgia road “prison farms” evolved and ended the private convict lease system among businesses.

Georgia’s chain gang history was a dark past. It included a reputation of harsh treatment, investigations, ruthless guards, bureaucratic corruption and attention in the national media. A 1930’s book and movie entitled, “I am a fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang” by Robert Burns brought national attention to the Georgia penal system and eventually helped to bring reform by Governor Ellis Arnoll. Also, Bartow’s own Rebecca L. Felton, championed this cause.

The competition to gain legislative approval and funding for a work camp was highly prized by local politicians. It meant that road improvements would be made for the community. Once a project was finished in one county, another district was wooing the legislature and State Highway Department to move the work camp to its location for a road completion project. Work camps were very often located by political persuasion. Camps were portable and designed to go where the job and labor was needed. The County Commissioner was always courting the Highway Department to gain some labor for a road improvement project.

In 1942, Bartow County once again won approval to have the work camp from Dallas, Georgia relocated just west of the city limits. (A former work camp existed in White, GA in the 1930’s.) Arthur Neal, county commissioner, announced the purpose of the camp was to complete work on several roads including the Rockmart-Taylorsville road, Dallas road, Rome and Canton roads.

The final site selected was property belonging to Mr. Herman W. Leake, a prominent land owner and mule dealer of the time. Apparently, this was land to be leased from Mr. Leake. According to records in the county tax office, this site was within land lots 593 and 560 near Petitt’s Creek and in view of Ladd’s Lime Stone Company. Today the site can be marked west of Ingles’ Grocery between the ACE Hardware store on the south side of the road and Shaw Industry plant number 13 parking lot on the north side of highway 113, Rockmart Road.

Construction began on the prison camp in late January and was planned for completion by the end of February. (It is important to understand that the Rockmart Road, Highway 113 as we know it today was not constructed over the hill at this time. Originally, if headed west, the road swung southwest behind the hill and crossed the old Pettit’s Creek iron bridge rejoining 113 in front of Ladd’s Farm Supply) The road was not built over the hill until after WWII.

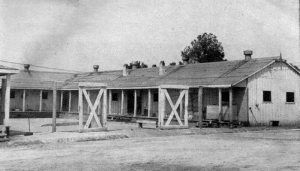

An initial U-shaped compound was constructed on the Ladd’s side of the Rockmart Highway. It was followed by a Guards’ Barracks House across the road about 50 yards away. These were meager dwellings of drafty wood frame construction, encompassed by a gated fence, barb wire and overlooked by a guard tower which stood to the right of the main barracks. They were built with a temporary objective and equipped with bunk beds, wood burning potbelly stoves and minimal electricity for lighting.

Local folks referred to these as the convict barracks. The barracks to the south (ACE Hardware) may also have been used to isolate disorderly convicts while the main barracks on the Ladd side housed the well behaved. About 100 convicts and 20 guards were transferred from the Dallas camp. Some convicts were “trustees” and had the run of the camp because of good behavior.

Cartersville Chain Gang Barracks/Courtesy of Life Magazine

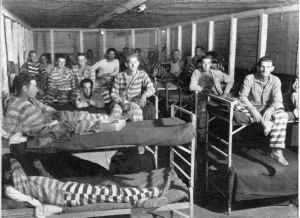

Work was long and hard, frequently ranging to 14 hours per day. Crews were transported to work sites and endured a day of breaking rocks, shoveling dirt and clearing brush. Convicts wore striped uniforms and ate a diet of boiled beans, cornbread, onions, cold fish and water. They were hobbled together by chains, often chanted while they worked and required to bow in the presence of the camp boss or captain. They removed hats and could not look a guard or camp captain in the eye when conversing.

Before the camp was constructed, it had already gained the nickname of “Little Alcatraz.” By 1943, it was under state investigation for brutally treating inmates. Conditions and treatment became so abusive that prisoners would self-inflict wounds to avoid work details. Convicts testified of being whipped by guards with a rubber hose. The camp was briefly closed down for inquiries after several breakouts and other abuses were disclosed.

A legislative committee recommended the removal of Warden Arthur Clay on charges of brutality, but he was later reinstated by Governor Arnall after the Prison Board found insufficient evidence to justify removal. In November of 1943, Life Magazine did a story on the convict camps in Georgia and showcased Bartow’s notorious Chain Gang Hill.

People in Cartersville and surrounding communities were fearful of the convicts and the impending threat of escapes. The general public had little compassion for convict suffering and asked few questions about how they were treated. The camp was in view of the Rockmart Highway and locals would drive around the compound with an uneasiness. Citizens held a poor opinion of the convicts and would often not speak of the camp.

Mrs. Eleven Rampley Bartlett, granddaughter of O. C. Rampley, can remember, as a 12 year old, visiting her grandfather at the camp. She was instructed not to speak to the inmates. She remembers that the warden had a small one-room office at the base of the guard tower with a bed and wood-burning stove. She remembers the bloodhounds were penned inside the outer fence to the rear of the main barracks in a small shelter. On occasion, she climbed up to the watchtower and looked down on the camp. She recalls seeing the guards carrying shotguns and rifles.

By 1944 the camp had been reassigned to Mr. Oscar C. Rampley, formerly the road foreman for the State Highway Department. He became the last camp warden until it closed. As the investigations continued, Marvin Griffin, then on the review board, would often inspect the camp and stay overnight with the Rampley’s. Prison reform eventually abolished the Georgia chain gang system due to cruelty exposed by the press. Mr. Rampley was instructed to transfer the inmates to Tattnall County and close the camp.

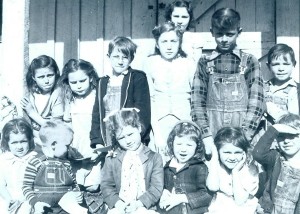

Times were difficult and housing was not plentiful in Bartow. People rented single rooms, stayed with relatives and lived where ever they could. Bartow’s Chain Gang Hill was fully decommissioned about 1945. As time passed, the barracks became occupied with tenants who likely paid rent to the Leake family. Tenants made personal improvements and lived in the make shift apartments. Mrs. Sara Munn and the First Presbyterian Church of Cartersville established an outreach Sunday School Ministry at the barracks for children who lived there. Little attention was given to the site from the time it was abandoned until the day it was destroyed. Long time Bartow residents recall passing it on the Rockmart highway and have some knowledge of its history, but not much detail.

As a young boy of five, I can remember visiting with my grandparents who lived in the apartments at Chain Gang Hill. My grandparents, Jeff and Augustus Bell Head lived there for several years. They were a cute couple, humble, full of humor, but poor with few material possessions. Granddad was a mechanic and grandmother was a traditional wife who never learned to drive, and was heavily involved with the Methodist church.

Jeff Head family in renovated barracks

When facing the barracks on the Ladd Mountain side, they lived to the left in the front quarters. I can recall warm memories of sitting in Grandma Augustus’ lap, captured by her stories and eating wonderful meals at her table. My grandfather worked for the State Highway Department. On some occasions I would spend the entire day there and can recall that a passing car offered the hope of a friendly visitor to break the boredom. Perhaps one of the most memorable and frequent sensations was the sudden blasting that would rumble from Ladd’s Mountain. Another was the sound of trains passing on the Seaboard railway between the barracks and Ladd’s Mountain.

My grandparents lived in a unit that consisted of about three finished rooms. Rather than sheet rock, I can remember that the walls and ceiling were covered with corrugated card board tacked up using RC bottle caps for reinforcement. The floor was partially covered with linoleum and bare planks also shown through in places with cracks that exposed Georgia red clay below. There were few electrical outlets. Overhead lights were suspended on electrical cords and naked bulbs on a pull chain. They heated with kerosene and wood stoves. Their apartment had been partitioned to include one of the bathroom units that served the convicts. The concrete bath had two toilets and one community shower that was equipped with four shower heads. Grandmother kept a chicken coup just out her back door and down the bank. I really enjoyed meeting relatives there on Sunday afternoons. My country cousins such as Ray Thacker, Mary Jo and Harold Brock would gather there for holiday meals or just to visit.

One of my older cousins, James Bouck from Illinois, visited our grandparents every summer from the age of seven until he was sixteen. Jim remembers the camp vividly. According to his account, there were five buildings and one guard tower. If facing the U-shaped compound, two smaller dwellings were to the right. One likely housed equipment and the smallest was the warden’s office. Another small house also existed to the west of the U-shaped barracks, down the bank and slightly to the rear near the chicken coup. Jim recalls these structures were uninhabitable or were filled with storage.

Elizabeth, Louise & Gossie Stone (March 1948) Cartersville First Presbyterian Church’s Mission Sunday School Class which met at Chain Gang Hill apartments.

As a young boy, Mr. Roy Tierce, a former resident in the early 1950’s, recalls that all the tenants paid rent directly to Mr. Jeff Head (Granddad) and he paid the Leake sisters when they came to collect.

It was a warm Labor Day Monday afternoon on September 6, 1954 at about 3:00. I was taking my midday nap on the bed in the front room that also served as a family living space. I was resting on a bed that was covered with a handmade quilt. A picture of some biblical scene was mounted on the wall above the bed. A radio used to listen to the Grand Ole Opry was on a large table nearby where granddad kept important papers and his time piece.

Leecy & Joe Head at renovated barracks

An enormous explosion woke me from my sleep. I knew it was not a blast from Ladd’s Mountain as it was too loud and too close. I bounced off the bed and was instantly grabbed by my mother. We went outside to see smoke and fire bellowing from the apartment on the opposite side. People were screaming and running from the fire. Debris seemed to be still falling from the air. Flames began to burst through the broken glass windows and leaped to the rooftop. My mother left me with my grandmother and ran across the road to call the fire department.

There was little anyone could do. In just a few minutes my sister, Beverly, who had been competing in the Miss Aquarama Beauty Pageant at the Allatoona Dam arrived to pick us up at 3:00. She called my father and grandfather. My grandparents tried to contain the fire with a garden hose, but it was too fierce. We stood at a safe distance in the dirt parking area next to the road. Mother held my hand. I saw people crying and shouting. Emotions ran high, confusion was everywhere. Things popped and crackled, we could feel the intense heat, walls collapsed, cars were moved to safety, people ran in and out of the rooms trying to save items. Tenants were throwing things out the windows and doors. The blaze traveled quickly around the U-shaped roof and consumed the barracks in about forty five minutes.

Joe & daughter, Meredith, with quilt

My grandparents had the most time of all, as their apartment was the last to burn. But even with those extra minutes they were not able to save but a few pieces of furniture, clothes, quilts and crockery. Precious items such as the family Bible, photos and family savings were all lost that day.

According to an account of the disaster in the Tribune News printed on September 9, 1954, the fire department arrived shortly after the call was received. Fire Chief, John Cagle said it was too far gone by the time they got there. The paper stated that the fire was caused by an oil-burning stove that had exploded. The article heading read, “Fire destroys old work camp: many homeless.” The barracks across the road fell into complete ruins and was razed in the 1960’s.

A half-century later, the legend of Chain Gang Hill still survives among deeply rooted Bartow families. However, the day it burned has left me with a tender legacy to share with family and friends that is very different from the dark side of Georgia’s Chain Gang history.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Meredith’s great grandparents: Jeff and Augustus Mae Head

To read a companion article on the Dark History of Bartow County Chain Gangs click here:

Interview Sources:

- Bartow County Tax Office: Mr. Billy Goodwin, Mr. Ralph McCary and Mr. Mike Floyd, 10/00

- Evelyn R. Bartlett, Granddaughter to Mr. Oscar Rampley, Warden, 11/25/00

- Randall Silvers, Local historian, 09/00

- Olin Tatum, former Bartow County Commissioner, 11/00

- Sara Munn, 11/6/00

- Arthur Lee Woody, former camp guard, 11/00

- Don Thurman, Bartow County Sheriff, 11/00

- Charles E. Head, 10/00

- Beverly H. Moore, 10/00

- Robert Harris, 10/00

- James Bouck, 12/3/00

- Ray Thacker, 12/1/00

- Roy Tierce, 3/2006

Printed and Video Sources:

- Life Magazine, November 1, 1943, pp 93-99

- The Bartow Herald, January 15, 1942, “Prison Camp Location Announced”, Cover page.

- The Bartow Herald, January 8, 1942, “Dallas Prison Camp Moves to Cartersville”, Cover page.

- The Bartow Herald, February 22, 1942, “Work Starts on Little Alcatraz”.

- The Tribune News, January 15, 1942, “Convict Camp Located West of Town; Work on New Structure Immediately”, Cover page.

- The Bartow Herald, June 16, 1933, “Convicts Located Here Turned Back By Highway Board”.

- The Bartow Herald, July 20, 1933, “Convict Camp Here Removed to Baker”.

- The Bartow Herald, October 28, 1943, “State Prison Camp is Closed Down Tuesday After 16 Make Get-Away”, Cover page.

- The Tribune News, October 21, 1943, “Moore Orders 11 Road Camps Closed Jan. 1”.

- The Tribune News, October 28, 1943, “Highway Work Goes Forward Despite Removal of Convicts, State Official Announced”, Cover page.

- The Tribune News, September 9, 1954 “Fire Destroys Old Work Camp; Many Homeless”, Cover page.

- History Channel, “Chain Gangs”, historychannel.com (1-800-708-1776).