By: Joe F. Head

Georgia’s chain gang system operated for almost 100 years and in certain instances concealed ghastly conditions that eventually earned it an infamous reputation for hotspots of dark brutality. Unfortunately, Bartow County equally caught high profile attention regarding cruel convict treatment. Periodically, Bartow camps became the epicenter of several state investigations that were featured in a national magazine, courts and major newspapers.

Following the Civil War southern states were faced with widespread destruction including the collapse of the penal system. Georgia was in shambles in the wake of war and particularly the loss of penal facilities, jails and prisons at local and state levels.

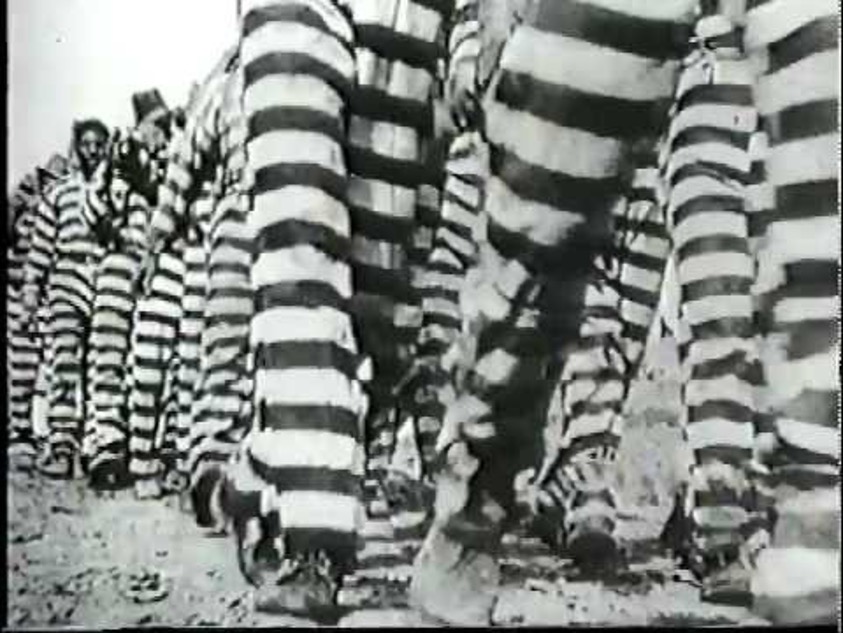

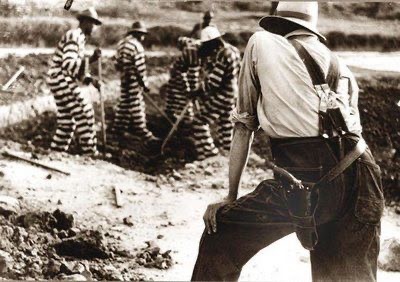

As southern states began to dig out of ruin there was little infrastructure left to manage incarcerations. In the Journal of the Georgia Senate Minutes on November 1866 page 24 – 27 a lengthy description appears describing the poor condition of the war ridden state penitentiary and great frustration in how to deal with prisoners. As a solution the penal system turned to a convict chain gang model that did not require brick and mortar facilities. This system operated on a field-based camp method and offered immediate advantages on several levels. It reduced the need to maintain prisoners and delayed the need to fund and build penitentiaries. Further it farmed out prisoners to supervised hard labor camp sites that provided imprisonment, discipline, food and shelter. Furthermore, it served as a divisive replacement for lost slave labor under the “colors of state law.” Typically, discipline was conducted with a strap and more severe methods were used for greater offenses. Each camp had an appointed “whipping boss” who carried out punishments. One report listed 112 registered whipping bosses statewide. The state maintained an annual whipping roster by name of prisoner that was filed with the state.

Joseph Brown, Georgia’s former Civil War Governor was one of the first to take advantage of the Convict Lease System. He contracted for 300 convicts and struck a deal with the state to rebuild the war damaged railroad system and, in doing so, made a fortune.

In 2006 the author of this research received correspondence from William A. Crump, Ph.D, Georgia State University Criminal Justice Instructor and former Assistant Commissioner of Operations, Georgia Department of Corrections. He addressed the origin of the convict lease system and the convict camp north of White in a topic entitled, Who Changed the Landscape of Bartow County Around White, Georgia.

His brief mentions that the convict lease system began in 1868 when the Georgia Military Provisional Governor, General H. Ruger implemented a law which permitted the farming out of the Georgia Penitentiary. On May 11, 1868 he leased 100 Negroes to William A. Fort of Rome to work in railroad construction, thus beginning the institution.

Soon following the launch of the convict lease system conditions became ill managed, notorious and corrupted. It was designed to relieve the state from shouldering the expense of convict upkeep with a deliberate revenue intent. The state invited bids from private interests to lease chain gangs for hard labor in mines, logging, railroad construction, sawmills, turpentine and other industries. As a side bar, many leases were let to third party private contractors who then managed the gangs for a client such as a mining company. These arrangements became breeding grounds for neglect, mismanagement, inhumane treatment, exploitation, disease and brutality. The chain gang lease system became a convenient revenue for the state, means to “legally press the underprivileged into bondage as well as a discreet tool to continue racial bias and a method to fuel cheap labor.” Records indicated that in most camps black convicts were largely the greater percentage of the population. However, some camps were more segregated.

The chain gang model approved camps at the state or county level for public works and private lease. However, as an unexpected outcome a third level of camps surfaced called “Wild Cat Camps.” These were largely unauthorized chain gangs that were assembled in counties from inappropriate conscriptions drawn from local jails. Unfortunate victims were shanghaied by various landowners or industries. Fines, bails and bribes would be paid by discreet individuals who removed jailed prisoners in chains to work for the period of their confinement. However, it was rare for the prisoners to be released on time or they fell to worse fates. These gangs were unregulated, ruthless and became dark operations that were outside the color of law. State officials struggled with these camps and attempted on many occasions to disband their existence.

Understanding the Chain Gang history in Bartow County is rather elusive and sketchy as camp identities were confusing. Basically, camps came and went over the years and were operated under nicknames or simply assigned a number. It was often difficult to determine if they were county, state, leased or wildcat operations. Camps were either mobile or stationary depending on the work and often their identity was determined by their duty.

Bartow County entrepreneurs were quick to take advantage of the lease system establishing a long history of operating a variety of chain gangs throughout the county. Primarily these early chain gangs replaced former slave labor in the construction of laying track, building roads, mining, timber and agriculture toil. Prior to the Civil War it was not unusual for local slave owners to lease their slaves to businesses in return for contract fees. Records found in this research reflect the presence of penal or incarcerated chain gangs operating from the early 1870’s through the early 1940’s.

Accounts discovered in this study reveal that Bartow had at least fifteen or more known residential chain gang camps and many other temporary or mobile camps that existed over seven decades. According to census reports most camp populations ranged from about 15 convicts to over 100 in each location. Camps were classified as either private lease for business or state/county operations for public projects. It was not determined in this study if Bartow had unauthorized wild cat camps. After the state lease system for private business interests was abolished in 1908, camps continued, but only as county and state operations. It was not unusual to see county or state chain gang road crews through the 1960’s.

The camps identified in this research were primarily stationary or residential camps as found in the US Census records, Grand Jury reports and newspaper articles.

| Hall Station Road Camp | (1870’s, Between Kingston and Adairsville on Hall Station Road) |

| Cartersville & Van Wert RR Camp | (1870’s, West of Cartersville adjacent to Hwy 113 to Taylorsville, 100 convicts) |

| Rogers Station Camp | (1870’s, Proximity of Iron Belt Road and Cassville Road, 100+ convicts) |

| Bartow Iron Works Camp | (1875, Lake Point Station area 50 to 150 prisoners) |

| Sugar Hill Camp(s) | (1880 -1908, NE Bartow County east of 411 north of White – 50 to 124 prisoners)* |

| Camp Bartow | (1900, Misdemeanor at Sugar Hill)* |

| Chumler Hill Mining Camp | (1901, 24 prisoners off highway 20) |

| Pine Log Camp | (1900, Area camps and possibly including Sugar Hill Camps 119 prisoners)* |

| Numbered County Camps | (1900, Area camps and possibly including Sugar Hill Camps 119 prisoners)* |

| Cartersville City Camp #2 | (1910, Lee Street and West Cherokee/Market Street proximity, 20 convicts) |

| Taylorsville | (1910, Taylorsville, 8 convicts) |

| Kingston Camp | (1906, Quartered in old school) |

| Pauper Farm | (1912, North of White on Hwy 411, 9 inmates) |

| Wolf Pen | (1912, 35 inmates) |

| Cross Roads Camp/ “Whites” GA | (1918, Camps 1 & 2 were merged and located to Adairsville, 27 inmates) |

| Chain Gang Hill Camp | (1940’s West of Ingles on Hwy 113 past ACE Hardware at top of hill, 34 – 96 convicts) |

According to the 1900 US Census the largest number of convicts was consistently centered in the Bartow convict camp around Pine Log District with 119 prisoners which may have included the Sugar Hill Mining Camp. Other camps recorded in the 1900 census ranged between 10 and 50 prisoners. Camps were both fixed locations with long term quarters and rolling camps using tents, wagons and camping equipment to move as the job progressed such as building roads or laying rails. Camps were appointed a warden, a “Boss or Captain and Whipping Boss”. Census records prior to 1910 most often list convict duties as cutting cord wood or mining. Great quantities of wood were necessary for making charcoal and firing the iron furnaces in the area.

As the lease system grew and chain gangs sprang up, so too did complaints and protests around the state emerge to abolish the practice. Bartow took a leading role in protesting the chain gang system. Among local leading voices were Bartow’s own Rebecca Felton, former Confederate General William Wofford, former Sam Jones Methodist Church Pastor General C. A. Evans and Judge Claude Pittman all wishing to extinguish the horrible institution called “Georgia’s Peculiar System”. General Evans became the state Prison Commissioner and testified at the 1908 Sugar Hill hearing that the lease system is radically wrong and needed reform.

On balance, the newspapers found in this research carried both sensational stories of mismanagement, filth and cruelty as well as positive reports on how well camps were conducted. The local papers often featured articles on road repairs and were complimentary of the quality of work. Frequently Grand Jury site visits determined acceptable conditions and satisfied prisoners, but also would cite areas for needed improvements. Chain gangs operated in a variety of capacities throughout the county in known and little-known locations. They were classified as County Misdemeanor camps or State Felony camps. Generally, reports included the number of prisoners, health, diet, sanitation, tools, number of sick or injured, escapes, budget, number of caged transport wagons (metal or wood), work wagons, livestock, road scrapers, negros vs white, male and female convicts and occasionally what work was being accomplished. Jury reports too often omitted camp identity regarding names, number or location which made it very difficult to understand sites. On several occasions reports would lean toward the abolishment of the chain gangs. However, the frequency and litany of reported abuses, hearings, deaths, whippings and investigations was painfully obvious.

During the February 1897 Grand Jury session, a full report was made of the Bartow Chain Gang Camp inspection. Matters were found to be in good order. However, the jury requested that a number of other bridge and road repairs be made and then asked the county to abolish the chain gang. In 1911 the Bartow Board of Commissioners voted to consolidate all the county chain gangs and to put them under one warden. Mr. H. K. Land was nominated and approved. However, no details were listed regarding the number or identity of camps.

The earliest documentation of chain gangs operating in Bartow County was in 1870 on the Cartersville Van Wert Railroad construction west of Cartersville and on the Hall Station Road. Newspaper articles referenced that smallpox had broken out in the Hall Station camp and doctors were dispatched to treat the prisoners.

The Cartersville and Van Wert (C&VW) Railroad was chartered in 1866 and 14 miles of track was completed by 1871, between Cartersville and Taylorsville using 100 convicts that had been leased from the state. (It is not certain if this was a rolling or fixed camp.) The railroad was plagued by shady management, unmet payrolls and reorganizations. As work progressed westward chain gang records appeared more in the Cedartown vicinity. As a result of corruption, by 1882 the road name had been changed to the Cherokee RR, followed by the East – West RR and now the remaining railroad bed is used to supply Plant Bowen (Georgia Power) with coal.

A second camp of 27 prisoners was established in 1919 on the Hall Station Road. The Grand Jury reported it was an ideal location and its operation was found in fine order. Surprisingly, the Jury stated it was too well equipped, over staffed, over stocked with farm animals, did not need motor trucks and recommended implements and some men be reallocated to other camps.

A Grand Jury report was made in August 1898 of the Bartow Chain Gang accounting for inventory and men. Items included 10 mules, 5 wagons, 3 road scrapers, harnesses and tools.

The force of men were 10 Negros and 8 white who were interviewed and found to be in good health and felt they were well treated. However, the tents were worn out and badly leaking.

Perhaps the three most notorious camps that operated in Bartow were the Bartow Iron Works Convict Camp near Emerson, Sugar Hill Camp near Pine Log Mountain followed closely by the 1942 Chain Gang Hill Camp west of Cartersville.

Sugar Hill Convict Camp

The Sugar Hill Convict Camp(s) were likely the most notorious operation in Bartow County. Located in north Bartow County northeast of White off East Valley Road in the upper Stamp Creek area at the base of Pine Log Mountain. It served an iron ore mining community and railroad operation that depended heavily on convict labor. This camp(s) operated from 1878 through 1909 when the Convict Lease System was abolished.

According to Dr. Crump’s correspondence, mentioned prior, there were eighteen different camps in Georgia in 1893. Four of these camps were in Dade County under one supervision and one camp of 51 convicts at camp Bartow (Sugar Hill). He refers to this location as nine miles north of Cartersville on the Rogers Railroad. These convicts were under Penitentiary #1, and lease control of the Dade Coal Company engaged in mining iron ore. Over time, as reports were submitted the number of convicts varied and companies in charge changed from Dade Coal to Georgia Mining and Manufacturing Company. An additional mention cites that I. B. RR. (Iron Belt RR Company) also had 23 convicts in 1899. His conclusion points to the convict lease labor system and mining companies as being key elements in who changed the Sugar Hill landscape around White, Georgia.

If by no other measure Sugar Hill was easily the most reported county camp in local and state newspapers regarding abuse and deaths. The August 1900 Grand Jury reported a list of mis-handlings at both the felony and misdemeanor camps that included self-inflicted wounds, severed toes, broken limbs, deaths, assaults, illnesses and crippling. They uncovered evidence of ill treatment, verbal abuse and a violation of no posted signage regarding rules and regulations for convict treatment. A scandal surfaced about paying wardens and guards under the table additional pay, supplements or bonuses beyond approved salaries.

According to newspaper articles and reported Grand Jury inspections Sugar Hill had both State and County camps in operation at this site. An inspection conducted July 24, 1902 found there were 84 state convicts and 53 county convicts working there. The same report included 48 convicts were at the Chumley Hill Mine. One prisoner was so badly injured that the attending physician recommended he be pardoned as he was paralyzed. On February 6, 1908 another inspection reported there were 76 state prisoners and 27 county prisoners at Sugar Hill. These reports validate that multiple camps operated simultaneously at Sugar Hill over a 30-year period.

The camp was hard labor, dangerous and a brutal private lease enterprise. Convicts were often poorly treated and inhumanely punished. Prisoners were frequently injured or killed in mining and rail accidents. Oral history supports a local legend of “Hangman’s Mountain” that was used as a sentence for violent or disobedient convicts who rebelled or committed aggression against guards or other prisoners. It was rumored that convicts would be taken to the mountain to either climb the steep cliff as punishment or simply to never return.

Prisoners complained of being ordered to perform work under hazardous conditions that put their lives at risk. Examples included being forced to work under heavy loading equipment, explosion zones, unstable mining cuts and overloaded train cars.

Cruel and lethal whippings would occur that often resulted in convict deaths. A charge of manslaughter was filed in 1900 against a Mr. Tomlinson for the whipping death of Mr. George Bankston. According to the investigation Bankston refused to work. A physician declared he was fit to work and following his refusal Mr. Tomlinson struck him with the strap 7 times. The next day he continued to refuse to work, and Tomlinson gave him 30 lashes and then 60 lashes on the third day. Mr. Tomlinson ceased lashing him, however the convict was found dead on the fourth day. The incident escalated into a full investigation resulting in an involuntary manslaughter charge. The commission eventually exonerated Tomlinson.

According to the August 13, 1905 Augusta Chronicle Deputy Warden J. W. Tierce at the Sugar Hill Camp was charged with the whipping death of a convict (Virgil Lidelle). The County Commissioner investigated the matter and heard statements from Joel Hurt owner, J. W. Tierce defendant and attorney Paul Akin, but to no satisfaction. The hearing resulted in the dismissal of Tierce and appointment of Mr. J. A. Carson as the new Warden. A Grand Jury investigation was ordered and eventually Tierce was acquitted.

It was not uncommon at Sugar Hill to witness fights among convicts and guards or guards provoking altercations. In some cases, guards would order convicts to assault or allegedly kill another convict. On one occasion an unusually large negro convict sentenced for five murders refused to come out of a mining cut and declared he would kill anyone who came in after him. A smaller convict volunteered to bring him out. Both were armed with picks. The larger convict swung his pick and missed, but the smaller convict’s pick swing caught his opponent in the cheek penetrating through the jaw and neck proving a fatal blow. The large convict was made to stand up where he was further beaten and chained to a tree where he died shortly after.

Frequent escapes and accidents were typical at this camp. A fourteen year-old boy was killed in a rock crusher accident, another convict was crushed under the wheels of a locomotive, another convict had his legs severed by a train car and a trestle collapsed injuring several men when the ore cars tumbled down the bank. In February of 1900 five negros overpowered two guards and gained freedom with only one being recovered. An August 9, 1900 Grand Jury report printed in the American Courant cited numerous incidents regarding accidents and negligence. It was noted that tram ore cars had crushed feet and severed toes to an alarming rate, diet was absent from meat, guards were found to be abusive, profane and relied on the whip too often. In 1906, the Grand Jury inspected the work areas and cited unsafe conditions regarding loose rocks, unstable dirt banks and rest areas too close to dangerous cuts.

In 1905 a controversy surfaced around Bartow County Commissioner Henderson as he was questioned about the legality of holding both the post of Whipping Boss at Sugar Hill and that of County Commissioner. While no one seemed to question his honesty or good faith many doubted his propriety or good taste of holding both positions posing a conflict of interest. As a result, he resigned as Whipping Boss and all parties were satisfied.

In 1905 a Grand Jury visit was made to the Sugar Hill Camp and it was reported there were 49 negro prisoners, 20 whites, two negro women and one white woman. It was found the convicts were well fed, well clothed and well housed. It was observed that officers treated the convicts humanely along with the sick and feeble. Convict ages ranged from 14 to 52 years old.

Bartow Iron Works Convict Camp

The Bartow Convict Camp was a privately leased unit under the joint authority of Mr. Harris and Mr. Stegall. They contracted with the Tennessee Coal and Mining Company in 1875 to provide labor at the Bartow Iron Works.

Among Dr. Crump’s correspondence cited earlier he mentions that a lease was granted to J. T. and W. D. on April 1, 1874 for Bartow Iron Ore for 180 convicts at $11.00 per capita per annum. Later the force was expanded to 235. Shortly after they subdivided the camp among several counties to make brick, raising iron ore and working on the Elberton Air-Line Railroad.

The Bartow Iron Works was primarily an iron ore mining community about one mile south of Emerson that is now the Lake Point Sports campus. It was a treacherous place as a result of frequent train accidents, assaults and mining mishaps, but also became a hotbed of convict injuries, escapes, mistreatment, health issues and deaths.

An early incident was a conflict between William Moore the Convict Manager of the Iron Works when he reprimanded a white one-legged convict. The convict cursed Moore for the action and Moore slapped the convict resulting in the convict landing a fatal stab to Moore’s side.

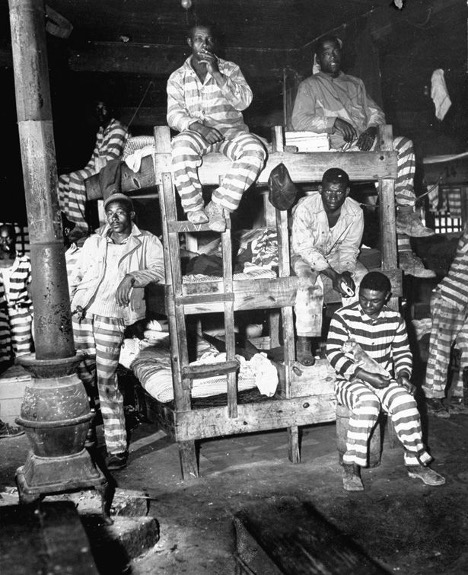

Under the Harris and Stegall 1875 lease the Bartow Iron Works camp consisted of about 50 prisoners who were shackled, chained and housed in a group of wooden shanties. Atrocities there reached extreme levels regarding inhumane treatment, hygiene and sickness. Complaints forced the Governor to investigate the camp.

Governor J. M. Smith sent Dr. V. A. Taliaferro to the camp on two occasions to inspect the conditions. On his first visit he arrived late in the day to observe dinner and saw a disgusting meal service that was void of proper cleanliness. He was shocked to see the quantity and quality of food served. Convicts were seated in a circle around a pit and not permitted to wash.

Trustees carried a wooden bucket filled with fatty fried meat. Each convict held out their shovel to receive a scoop from the bucket followed by a trustee distributing bread and water. He found the meat to be poorly cooked and was informed the diet rarely changed. He learned the diet typically consisted of poor cuts of fatty pork, bacon, beef, molasses, bread, seasonal vegetables and water.

Dr. Taliaferro declared the camp cook, Sarah, to be the filthiest woman he had ever seen in his life. He inspected her and found her body unwashed and clothes to be infested with vermin.

His further inspection of the camp found frequent evidence of inhumane treatment, deaths, tales of harsh punishments, escapes, no fresh clothes and illness. Dr. Taliaferro found poor sleeping quarters filled with old straw and lice. He discovered diseases including scurvy, rheumatism, consumption, syphilis, diarrhea, frost bite, dropsy and old age disorders. His inspection uncovered little to no medical quarters nor supplies on site.

He examined their work schedule and found it to be comparable to regular mining employees and determined prisoners work no more or no less than paid laborers. However, he was not pleased with how restricted they were to water and instructed water to not be rationed nor out of reach.

At the conclusion of his second visit, Dr. Taliaferro recommended to the governor that the camp is bordering on a case of morality and should be closed. At his recommendation Governor Smith annulled the lease contract and asked Dr. Taliaferro to transfer the convicts to a location for treatment and preparation to be bid out to another leasee.

However, additional research discovered that subsequent chain gangs operated at the Bartow Iron Works. Following the disbanding of a camp in Cole City in 1896 by order of the Governor, 400 convicts were moved to new locations. Governor Atkinson granted permission to establish a new camp in Emerson and named J. A. Bennet as whipping boss. An article on the health of state convicts in the Macon Telegraph reported that in 1901 there were 149 convicts working at the Bartow Mines. In 1908 seven convicts escaped and boarded a fast bound express train. Bloodhounds were used in tracking one convict who was apprehended in Rome, Georgia.

Roger’s Station Convict Camp

Rogers Station was a stop on the Western and Atlantic Railroad located in the vicinity of Iron Belt Road and Cassville Road north of Cartersville. This location also was the site of an iron furnace and mining operation.

In 1880 a committee was appointed by Judge McCutshen to visit the Roger’s Camp. The committee reported that there were 40 men mostly negros working along the railroad.

The men were housed in log buildings but slept in filthy bunks. Six men who claimed to be ill were chained to their bunks. Food rations were deemed sufficient allowing each man ¾ pound of meat daily, cornbread and vegetables as available. They began work at day light, took an hour and half lunch break and worked till sunset.

In July of 1880 The Macon Telegraph reported a dispute at the Roger’s Camp between two guards resulting in the shooting and killing of one of the guards. No charges were filed as the shooting was viewed as justifiable.

The Savannah Morning News reported on November 9, 1900 two convicts were killed on the Iron Belt Railroad while running from Rogers Station to the Sugar Hill mines. An officer also broke his shoulder in the accident.

Sundries (Reports,Services, Appreciations, Accidents)

In 1897 State Convict Camp Inspector Phill Byrd submitted a shocking report to the Governor regarding the state’s county misdemeanor camps (public and private). Byrd states he visited 51 chain gang camps containing 1,792 convicts. As a practice he made a rule to take each camp completely by surprise in order to discover the reality of conditions and treatment. His findings were graphic, horrific and quantitative regarding gender, personnel, race, ages, death rates, diet, methods of punishment and brutality. He reports briefly of visiting the Bartow camp and found all prisoners housed in floored tents year-round with good stoves and ample bedding.

Overall, his final report revealed harsh treatment, poor housing, poor hygiene, poor sanitation, illness and sickening smells across most camps. He noted that county camps were more often operated slightly better than private. In most instances 90% of the convicts were black and about 1% female. Byrd concludes his report by comparing convict bondage was worse than slavery in many camps. He encourages the governor to systematize and regulate the institution and move it toward reform including finding milder punishments for lesser grades of crime.

Some news accounts reported that local ministers such as Rev. Dunbar would preach monthly to the Bartow County Camps, while other news reported that citizens would hold Sunday picnics with a wide spread of food expressing appreciation for the good work the convicts had done in their neighborhoods. In December of 1920, Rev. Dutton of the First Baptist Church held a Christmas service for the convict camp off of the Dixie Highway near Jones Mill. A sermon, meal and a present were given to each prisoner.

In 1922 the state reported it had 7,667 in the penal population. The report included prisoner illnesses, deaths and comparisons of previous prison populations.

It was not uncommon for newspapers to report varied accidents among the convict road projects. In particular there are several reports of train and dynamite injuries. One explosion was covered in detail that occurred at the Douthit Ferry Mountain near the iron bridge.

Grand Jury Reports

In February of 1912, the Grand Jury submitted an extensive report covering a vast number of topics. One of which was a visit to the convict camp (identity not listed) holding 48 prisoners and Pauper Farm stating only that bedding was in need of replacement. They accounted for mules, equipment, diet and budget. A rather poor report of the jail was included that requested repairs, clean out filth, improve garbage removal, increase daily funding to 0.50 cents per prisoner to provide for better meals and make exterior improvements to the facility.

A November 1912 report was made in the Cartersville News of an unusual site visit to several road projects on the same day to observe work at three locations. The first was in south Bartow on roads leading to Kennesaw to see a new method of using topsoil to build roadbeds that might be used in Bartow. This same day trip was followed by inspecting 9 inmates housed at the county Pauper Farm near White. Discussions centered around how well managed the farm is and the hope to move the farm nearer Cartersville. The jury continued on to Wolf Pen and then White where they found about 35 convicts doing satisfactory work on the dirt roads.

Honor System

In 1912, a forward-thinking Warden, Mr. Land supervising a county camp of 50 convicts introduced the Rule by Honor System. He abolished chains and shackles in return for good behavior and fair treatment. He established a set of rules and if any were broken the accused would have a fair trial among his fellow prisoners and punishment, if determined by his peers. The prisoners were so grateful, not one escape has been attempted.

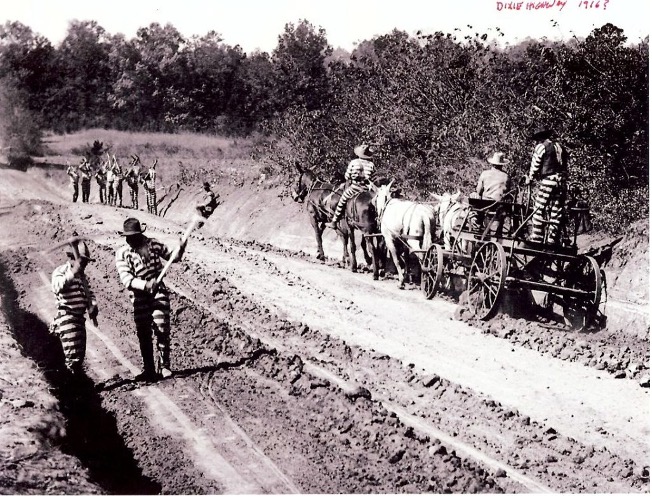

Dixie Highway Work (cover photo)

In 1913, the Bartow Chain Gang worked on the road between Cartersville and Emerson. The Georgia Peruvian Ochre Company provided fill dirt for the roadbed followed by a topping from the Bartow Iron Mine. The community and county were extremely pleased with the outcome.

In 1918 two reports appeared in the Bartow and Cartersville News reporting that Camps 1 & 2 (“Whites” and Adairsville) have been consolidated and moved to Adairsville. An inventory listed: twenty-seven inmates (8 white and 21 colored), twenty-four mules, one horse, eight hogs, two Nash trucks, nine two-horse wagons, three 99 steel plows, one Oliver plow, one concrete mixer, two road scrapes, one six horse scape, three drag scrapes and one gasoline engine. At the old crossroads camp (Wofford Crossroads) the following stock remains in shacks: 10 mules, 13 hogs, 3 pigs, 7 bunks, apparel, 3 convict mobile steel cages, 7 wheel scrapes, blacksmith tools, 1 horse wagon, concrete mixer and a gasoline engine. The committee recommends that much of the surplus be sold and other items to be stored for future use.

Chain Gang Hill

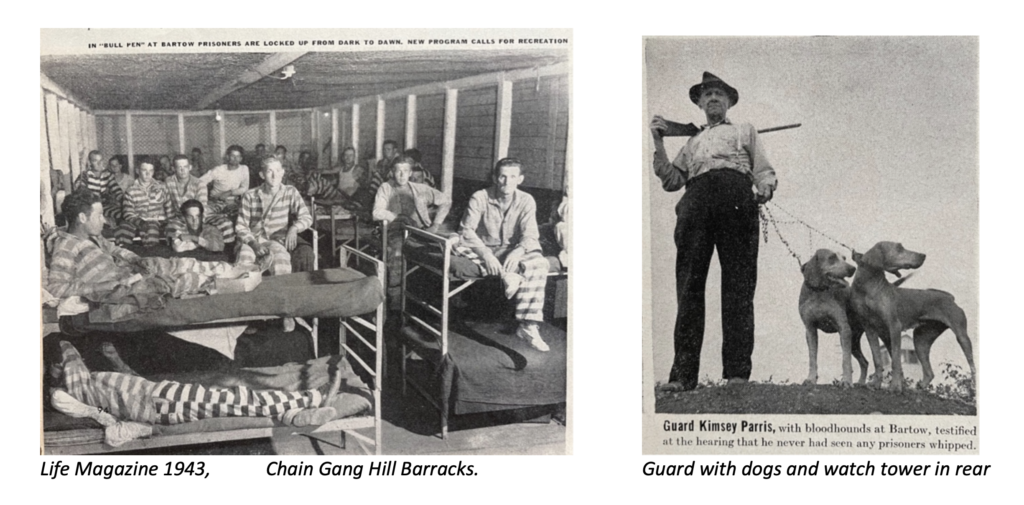

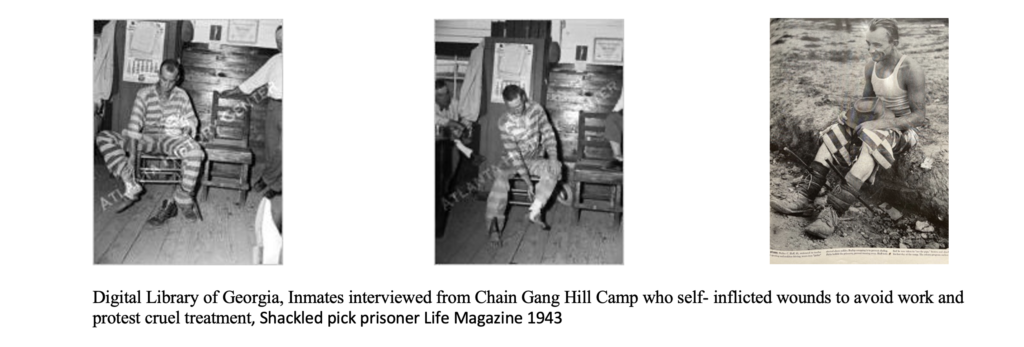

The last residential chain gang to operate in Bartow County was known as Chain Gang Hill or Convict Hill west of Cartersville on highway 113. This camp was transferred from Dallas, Georgia and put under state management to complete the Rockmart Road project (Hwy 113). In the March 12, 1941 Tribune News Warden Ed Goble from Dallas reported that he would move the camp from Paulding consisting of 96 Negros, twelve guards and equipment. The article indicated that the Cartersville camp is one of thirteen camps maintained by the state. It operated between 1942 and 1944. Bartow County assisted in constructing the property consisting of a fenced compound of 5 or 6 wooden buildings composing prisoner quarters, commissary, separate mess halls for guards and prisoners, office, watch tower, supply shed, guard and Captain quarters. Much of the construction labor was provided by the prisoners. It held about 100 prisoners, 20 guards and arrived with a reputation of “Little Alcatraz.” There were frequent escapes, harsh treatment, rubber hose whippings and injuries. During its operation inmate population was reported to range between 47 to 100 men.

Correspondence acquired at the Georgia Archives revealed that Governor Arnall requested the Chairman of the State Board of Prisons to increase the number of convicts at several camps in order to expedite work. Cartersville was included to add ten men in this request. Documentation was found that listed the road project routes this camp was assigned to service consisted of: Highways 3, 20, 61, 113 and 140 totaling 110.3 miles of roadwork. However, its main purpose was completion of the Cartersville to Taylorsville (113 Hwy) road construction. Once the camp was established rumors of mistreatment emerged.

Georgia’s Chain Gang reputation attracted the attention of Life Magazine followed by a visit to the state including Bartow County’s Chain Gang Hill facility. While several camps in Georgia were featured, Bartow’s Camp was the leading story. Photography and interviews were witness to a harsh system that turned public opinion to demand the abolishment of the chain gang system.

On September 23, 1943, Senator Claude Pittman from Bartow county presented to the local Lions Club on “State Prisons offer a living hell to inmates.” He lectured that the senate committee on prisons had interviewed prisoners at the state highway camps and learned of harsh conditions and treatment. He lobbied strongly for its abolishment.

At the Chain Gang Hill camp, it was not uncommon for prisoners to walk off, escape or self-inflict injuries, slice tendons or break legs to avoid hard labor. In 1943, charges were made against Warden A. W. Clay for whippings, verbal and abusive treatment of camp prisoners.

The Senate Penitentiary Committee found that Clay and a seven foot, two-inch tall guard, Big Jim Bryant had falsely testified about concealing whippings and should also be wearing stripes. Following a Life magazine feature exposing harsh treatment at the Bartow camp Governor Ellis Arnall ordered that the camp be disbanded and prisoners to be transferred.

On August 31, 1943 additional documentation in the State Archives from Governor Arnall found that the Governor requested a report on the Bartow County Highway Camp investigation alleging mistreatment by Mr. A. W. Clay. This review resulted in the reinstatement of Mr. Clay without prejudice, free of fault and guilt. However, on orders of Wiley Moore, director of prison operations the camp was closed before the end of the year and prisoners were transferred to the Tattnall County prison.

Conclusion

Bartow County chain gangs were not unlike others that operated in the State of Georgia. In fact, there were news articles and state reports (good, bad and ugly) of even more ruthless and violent camps in South Georgia that used more torturous methods. It was not uncommon to find reports of sweat boxes, knotted whip straps, dogs set upon prisoners, convicts staked out in the sun, neglected infections, ankle spikes, shackles, prisoners suspended from trees or bound in contorted positions and food or water were withheld.

As a result of these abuses, Bartow County was singled out by a 1943 Life Magazine story. Additionally, a book and movie entitled, “I am a fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang” by Robert Burns was published. These exposures drew attention to the mistreatment of convicts, embarrassed state officials and helped to demand change.

In light of a harsh penal system that existed for nearly a century, Bartow can boast of the many local and influential voices that championed the cause to abolish the entire state chain gang system. We pay tribute to those local heroes who advocated for the eradication of chain gangs and are saddened for those who suffered unnecessarily in a cruel, archaic system.

To read a companion article on the history of Chain Gang Hill click here:

Acknowledgement

This article would not have reached the detail and depth of history had it not been for EVHS member, Mr. Sam Graham. His generous contributions from personal files and his additional research efforts in searching digital newspaper sources made this a much richer work. Thank you, Sam!

Bibliography

Note: Some article titles were not available or have been altered for formatting andspace

Books

Slavery by Another Name, Douglas Blackmon, January 2009

Newspapers

The Atlanta Constitution, Joyously Convicts Leave Custody of Lessees, April 2, 1909

Greensboro Herald, The Cartersville & Van Wert Railroad, February 2, 1870

Cartersville & Express, Story of ride on the Cherokee RR to Taylorsville, August 15, 1891

Standard & Express, Communicated (Editorial), March 28, 1872

Savannah Morning News, Penitentiary Convicts, April 11, 1874

Georgia Weekly and Telegraph, Cartersville Telegram to Rome, Bartow Iron Works, July 6, 1875

Weekly Sumter Republican Americus, A Terrible Record, May 21, 1875

The Georgia Press, Georgia Governor abrogates lease, May 18, 1875

Cartersville Express, Notice of Convicts at Cherokee Railroad & Rogers Iron Works, April 8, 1880

The Free Press, Report of the Convict Committee, July 22, 1880

Macon Telegraph, Removal of 400 Convicts, August 5, 1896

Macon Telegraph, Health of Convicts Good, August 24, 1901

Atlanta Georgian and News, Seven Convicts Escape from Gang, April 15, 1908

Augusta Chronicle, Whipped to Death, August 13, 1905

Cartersville News, Kingston, May 17, 1906

Atlanta Georgian and News, The Holder Bill Gives us Five More Years of This, July 22, 1908

Atlanta Georgian and News, A Battle With Picks, July 30, 1908

Atlanta Georgian, Seven Convicts Escape, April 15, 1908

Marietta Journal, John Neill Killed at Sugar Hill, April 16, 1903

Northeast Georgian, The Penitentiary Convicts, April 11, 1874

Macon Telegraph, Conflict Between Guards, July 30, 1880

Macon Telegraph, Bartow Abolishes Chain Gain, December 27, 1895

Macon Telegraph, Removal of 400 Convicts, August 5, 1896

Courant American, Bartow Chain Gang Abolishment Recommended, February 4. 1897

Courant American, State Convict Camp County Chain Gang, August 4, 1898

Courant American, Mr. Tomlinson, May 4, 1899

Courant American, They Over Power Guards, February 15, 1900

Courant American, From the Grand Jury, August 9, 1900

Cedartown Standard, Tomlinson All Right, August 19, 1900

Courant American, Captain Tomlinson Friends, August 23, 1900

Savannah Morning News, Convicts Killed, November 9, 1900

Courant American, Sugar Hill and Chumler Hill Inspected, January 31, 1901

Cartersville News, White Convict Killed, Loses Legs, April 4, 1901

The News Courant, Convict Camps, July 24, 1902

Marietta Journal, John Neill Killed, April 16, 1903

Cartersville News, County Chain Gang, January, 26, 1905

Augusta Chronicle, Whipped to Death, August 13, 1905

Cartersville News, Henderson Resigns, May 18, 1905

Cartersville News, Chain Gang, November 15, 1906

Cartersville News, Convict Camps, February 6, 1908

Atlanta Georgian News, Convict Charges Leg was Crushed, July 27, 1908

Athens Weekly, The Statement, Wild Cat Camps, August 7, 1908

Atlanta Georgian, A Battle with Picks, July 30, 1908

Atlanta Georgian, The Holder Bill Gives us Five Years More, July 22, 1908

Atlanta Georgian, General C. A. Evans Admits Lease System is Bad, August 7, 1908

Cartersville News, Vote to Consolidate County Convict Camps, April 13, 1911

Cartersville News, Convicts Hurt by Dynamite Blast, February 2, 1911

Clayton Tribune, Picnic Celebration Dinner, October 6, 1911

Cartersville News, Bartow Grand Jury Recommends Bonds, February 6, 1912

The True Citizen, Convicts Ruled by Honor, August 31, 1912

Cartersville News, Splendid Work on Roads by Chain Gang, March 6, 1913

Cartersville News, County Chain Gang, May 5, 1918

Bartow Tribune, Two Convict Camps Consolidated, July 25, 1918

Bartow Tribune, Grand Jury Presentments, January 30, 1919

Bartow Tribune, Convict Camp, November 4, 1920

Bartow Tribune, Christmas Service, December 23, 1920

Bartow Tribune, County Road Gangs Does Good Work, April 14, 1921

Tribune News, Convict Camp Being Occupied, March 12, 1941

Tribune News, Convict Camp Location Insures Completion, January 8, 1942

Tribune News, Prisons Offer Living Hell to Inmates, September 23, 1943

Oakland Tribune News, Georgia Reforms Prison Camps, March 26, 1944

Miami News, Georgia Reforms Hell Camps, December 12, 1944

Articles, Correspondence, Reports and Exhibits

Georgia Senate Journal Minutes, State Penitentiary and Chain Gangs, November, 1866

Letter, Dr. William Crump, Who Changed the Landscape Around White, GA, February 8, 2006

Reinhardt University, Spirits of Log Mountain Exhibit, 2021 Dr. Donna Little

Etowah Valley Historical Society, The Legend of Chain Gang Hill , Joe F. Head, December 2000

Digital Library of Georgia selected photos

Life Magazine, Georgia Prisons – State Abolishes Old Abuses, November 1, 1943, pp 93 – 99

North Georgia Journal, A Look Back at The Chain Gangs, Gordon D. Sargent, Winter 1996

Report of Special Inspector of Misdemeanor Convict Camps of Georgia, 1897, Phill G. Byrd

Letter, Ellis Arnall Governor, Clem E. Rainey, Chair of State Board of Prisons, August 12, 1943

Letter, Ellis Arnall Governor, Clem E. Rainey, Chair of State Board of Prisons, August 20, 1943

Letter, Ellis Arnall Governor, Clem E. Rainey, Chair of State Board of Prisons, September 6, 1943

Executive Order, Ellis Arnall Governor, September 10, 1943

Digital Library of Georgia, UGA

Census Records

1880, US Census, Georgia, Bartow County, 822 District, June 26, Pages 43, 70, 71, 72, 73

1900, US Census, Georgia, Bartow County, (no location) Sheets 12, 13-A, 13-B, 14, 22

1910, US Census, Georgia, Bartow County, Pine Log District, April 23-25, Sheets number 2, 5

1910, US Department of Commerce Census, page 216

1920, US Census, Georgia, Bartow County, (no location) January 3, 1920, Sheet number illegible