By: Sanford Chandler, Ed.D.

I received a note from Mr. Ronnie Yancey asking for my assistance. Mr. Yancey was attempting to visit the burial site of one of his relatives in an abandoned cemetery behind Toyo Tire Manufacturing, Company. He asked if I could assist him in gaining access to the site.

Making a few calls and emails to friends, I finally gained approval to visit the site. It was through one of these calls I discovered that Carl Etheridge had completed the original Cemetery Survey in 2003.1 My next call was to Carl. We arranged to meet and visit the Cemetery together.

Carl and I met in the parking lot of the Hickory Log Personal Care Home. A modern brick facility that in many ways carries on the tradition of assisting those less fortunate in our community.

Carl had not been back to the Cemetery since 2003, when the survey was completed. By the time we arrived on the site most of the original land marks, roads into the area, and surrounding forest had changed. It was evident that Mother Nature was taking back that which was hers.

I found myself pushing through brambles and briars, ducking under low hanging limbs, jumping over drainage ditches, and stepping over fallen tree trunks as we searched for the cemetery on a beautiful crisp fall day. The sky was splattered with Cumulous clouds and the sun forced its rays through the trees and onto the forest floor.

Maneuvering along the lower slopes of Little Pine Log Mountain, I couldn’t help but think how this Mountain, in the not too distant past, was teeming with mining activity. Today these industrious activities have given way to Mother Nature’s reclamation.

The once prominent light-rail track moved load after load of mined materials from the mountain to White. The numerous community buildings, connective roadways, and mining camps all in support of the substantial mining industry were all gone, reclaimed by nature.

After a few minutes of orienting ourselves, Carl called out, “it’s over here!” The pioneer era cemetery came into view. It was located along one of the lower slopes of the mountain in a somewhat flattened slope. It was bordered by and abandoned roadway and a pasture. To the North was a chain link fence separating the cemetery and the mountain from a large manufacturing company. When the cemetery came into focus I could see the depressions and fieldstone markers—they were too numerous to get a quick count.

Unable to make a complete count of the graves, Carl pulls out his 2’ x 3’ map and said, “I found 483 graves here in 2003!” I was shocked. The original survey revealed the location of 166 grave sites identified by depressions and fieldstone markers and another 317 by remote sensing and probing. This was the largest abandoned cemetery I have ever seen. This was what was and still is called “The Paupers Cemetery.” Individuals have referred, incorrectly, as the Poor House Cemetery, Hickory Log Cemetery, Bartow County Farm Cemetery, among other identifiers.

The records from the Bartow County Farm or Pauper House were transcribed by Jane B. Thompson and Laurel Baty. It is from this transcription that I began uncovering the personal stories of some of those living, dying, and laid to rest on the Farm.2

The Cemetery is a two acre set-aside of the original 330 acre Bartow County Farm (Farm)— the Paupers or Poor Farm by most all references and I will use the term Farm to describe the institution herein.

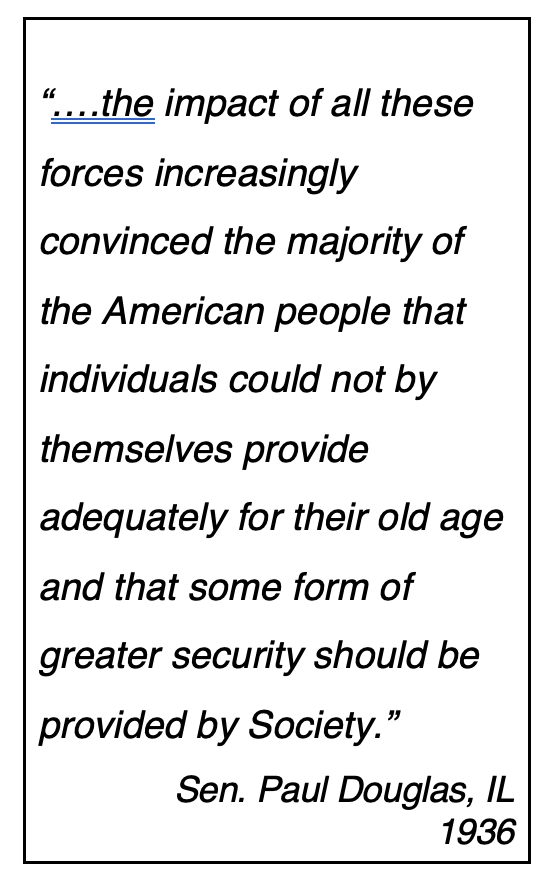

The Farm itself is a pre-welfare institution. These institutions were literally spread across the nation and were the conduit whereby the communities, cities, and counties assisted those unable to care for themselves. Bartow was no exception. The Farm provided support and assistance to widows, orphans, single mothers and children, the aged, those who were mentally ill, and those with highly contagious diseases. It was not until the early 1930s that the nation, as a whole, began to discover the substantial need for a national system to care for these individuals. Senator Paul Douglas, seemingly convinced of the need stated, “The impact of all these forces increasingly convinced the majority of the American people that individuals could not by themselves provide adequately for their old age(d) and that some form of greater security should be provided by Society.”

Disease was prominent in these institutions during the19th and early 20th Centuries. The Farm records reveal numerous payments to physicians and others for the care of individuals housed there.

Small Pox had a dramatic effect on the individuals, the economy, and families of the area.7 An article written by Matthew Gramling gives a precursor of what Bartow County would face in just a few short years dealing with Small Pox.

Those contracting the deadly Small Pox among other diseases were sent to the Farm or to the Pest House2,3 at Stilesboro. Records reveal that in order to treat, house, and care for these individuals it became a substantial expense. It is thought that many of the unidentified souls interred in the Paupers Cemetery were victims of Small Pox or other contagious infections.

The Farm itself was established in the1860s and originally consisted of “a number of stark wooden frame row houses that were built side by side.” “A nearby open cut ore mine was also named the Pauper Mine. Mineral rights…were reserved by several ore companies.” 4 The Farm also included a building serving as a church.

The connection between the Farm and the Pest House or Pest Hospital in Stilesboro— some 17 miles distant—is omnipresence in the Farm records. Small Pox was prevalent between 1866 and 1871 and, in fact, the Farm recorded on “October 3, 1870, a receipt to the RRd for $18.00 for tent for use of Small Pox Hospital.” It may be assumed that the tent was some temporary measure to assist with the overflow of patients.

The Farm records help to measure the severity Bartow County faced with this horrible disease. The Farm provided medical services, courier, supplies, guards, and nursing to the Pest House and the records indicate that the Farm took the financial lead. Although the Farm was not immune to having cases within its own confines, most seem to have been transferred to the Pest House from the Farm. Several cases were found in Farm records and medical services that were required to treat the disease.

Those individuals unfortunate enough require the assistance of the Farm ranged in age from 7 months to 91 years. These individuals were called inmates on the Farm and throughout the records are referred to as such. The Farm itself is recorded as being called the Pauper or Poor Farm. The inmates’ average age was 46.6 years and in 1872 it cost approximately $92.00 per year to care for each inmate. Whites, blacks, women, men, and children, at some point, occupied space on the Farm. Those who could work did so on the farm. Being destitute played no favorites and individuals from all ages and backgrounds came to the Farm for assistance.

Death came in many forms on the Farm. Pneumonia is recorded on at least one death certificates and Robert Campbell died from a snake bite. His obituary reads:

“We are informed by Mr. W.J. Collins, keeper of the pauper farm, that Robert Campbell, an aged inmate of the Bartow poor house, was bitten by a rattlesnake Monday afternoon about four o’clock. After lingering in the greatest agony he died at 12 o’clock on the same night.” The snake was about four feet long and had eleven rattles.”5 Robert was interred in the Paupers Cemetery.6

At least one baby was delivered on the Farm and quite possibly more but the records simply don’t record but one such incident. The baby was delivered during the month of February 1872. The receipt reads. “To Mrs. M. Ford for 1 case of midwifery—5.00.” There is no evidence that the child was conceived on the Farm but it is possible as some families were housed there as well as individuals. Or, she may have come to the Farm for assistance in delivery which in all probability was the case.

At least three (3) mothers were left with the difficult decision as to what they were to do with their babies and small children. Some of the more fortunate were able to turn to their relatives while others found the Farm as a respite. At least three are documented as giving away their children.2

One mother gave up her daughter to J.D. Enlow. The farm records state, “Mother, who is inmate at Pauper Farm consents that her daughter, Martha Brown, should be bound to J.D. Enlow until she is 21.” There is no record of the age of Martha Brown.

Another mother, Jane Barnes, “authorizes me to say that she is willing for her child to be bound to Martha Jones.”

The Cofer family which consisted of a husband, wife, and two children gives notice to “Eveline Cofer, next of kin” but fell short of revealing what might have befell the family. However, by July 1, 1878, the records show that “Lindsey Johnson has applied to have Matthew Cofer a minor in the Pauper farm of said county and about eight years of age bound to him in terms of the statue.”

The hardships of the inmates prior to, during, or following their tenure on the Farm was taken with them to their graves. Life stories, diaries, or other written documents have escaped recording. We will forever wonder about their fates, suffering, and the feelings they must have held as inmates. In many cases these individuals were branded as morally unfit by the communities, outcasts if you will. This is not to say that many didn’t overcome their situations but we simply do not have a record of this.

The Cemetery Records6 of the Pauper’s Cemetery and actual Death Certificates reveal short stories of how some of the inmates lived and died. All were interred in the Paupers Cemetery.

- May Brinkley, a single white female, age 18. She was attended by H.B. Bradford, M.D. from June 22, 1921 through July 22, 1921. The official death certificate stated that she died at 1:00 PM July 22, 1921 from “Syphilis and Pellagra.” Pellagra was a Niacin deficiency which leads to horrible, debating skin symptoms. The cause of the disease was most evident when the diet consisted of Corn Meal, Molasses, and lesser desirable cuts of meat. Ms. Brinkley has no record of a birth date or other family members, nor why she was on the Farm.

- Albert Absolan Nation, a single white male, age 63 was attended by H.B. Bradford, M.D. He was born in 1856 to Jesse and Lucretia Johnson Nation who were living in Murray County, Georgia. He was under the care of Dr. Bradford from January 5, 1920-January 18, 1920. He died on January 21, 1920 of “Broncho-Pneumonia, Pleurisy Right Side.”

- Pamelia W Crosson (Crossen), a single white female, age 72. She was attended by H.B. Bradford, M.D. on March 25, 1921. She passed away at 1:00 AM on March 26, 1921. The cause of death as reported by Dr. Bradford was, “Burn of anterior and posterior of arms, legs & body of 2nd degree.” Ms. Crosson’s brother, William, was interred in the Paupers Cemetery in September 14, 1920. He was 77 years old. Several of Ms. Crosson’s family members were interred in cemeteries in Coffee County. Little more is known as to why she and her brother were on the Farm.

The Paupers Cemetery is home to some 483 graves. We simply do not know the actual number of individuals that passed through the Farm or gained some type of short term assistance. Some went on to be successful in their own right while others are interred on the slope of Little Pine Log Mountain.

Their stark graves marked by fieldstone or a simple depression in the ground is all the record we have of them. Hopefully, someday someone will uncover more information regarding these individuals so they can be named and recognized as our ancestors with the humanity and dignity they deserve.

Appendix A – Deaths and Burials

Find-a-Grave list five (5) memorials in the Paupers Cemetery, and two (2) in the Pest House Cemetery.6 The individuals listed on this site are:

Paupers Cemetery (AKA Bartow Poor Farm Cemetery)

| Name | Birth Date | Death Date | Burial |

| Brinkley, May | Unknown | 22 July 1921 | Paupers |

| Campbell, Robert | Unknown | 17 August 1878 | Paupers |

| Crossen, Pamelia W | 1848 | 26 March 1921 | Paupers |

| Crossen, William Thoma | 16 February 1843 | 14 September 1920 | Paupers |

| Nation, Albert Absolam | 1856 | 21 January 1920 | Paupers |

Pest House Cemetery

| Name | Birth Date | Death Date | Burial |

| Ash, Maring An Stroup | 15 August 1829 | 7 July 1863 | Pest House |

| Knight, Joshua | 1794 | 10 May 1849 | Pest House |

Paupers Cemetery (AKA Bartow Poor Farm Cemetery)

Note: These individuals were obtained from the Bartow County Farm Records by the Author. Corroborating evidence is not presented. The two sources of the following information was taken from the Farm records or from obituaries found in newspapers.

| 18 January 1872 Name11 December 1872 Name | Birth Date | Death Date | Burial |

| Emerson, | Unknown | 5 November 1867 | Paupers |

| Hammond, | Unknown | December 1868 | Paupers |

| Mitchell, Ben | Unknown | 8 June 1870 | Paupers |

| Howell, | Unknown | 22 July 1871 | Paupers |

| Freedman, | Unknown | 29 October 1872 | Paupers |

| Gibson, L. | Unknown | 21(29) October 1872 | Paupers |

| Goodson, Mathew | Unknown | 11 December 1872 | Paupers |

| Hazel, Wm | Unknown | 18 January 1872 | Paupers |

| Wilson, Baby | Unknown | 30 September 1872 | Paupers |

| Hill, M.T. | Unknown | 2 September 1873 | Paupers |

| Campbell, Robert | Unknown | 22 August 1878 | Paupers |

| Felton, Lucy | Unknown | 16 (14) September 1880 | Paupers |

| Donald, Johnnie | Unknown | 6 September 1888 | Paupers |

| Doyle, | Unknown | 7 November 1889 | Paupers |

Appendix B – Transcribed Farm Records

Graves were dug, coffins made, bodies shrouded, and burials were recorded in the Farm Records. The records do not always coincide with the death of individual on the Farm but all these records were paid through Bartow County Farm resources and all are assumed to be for individuals residing at the Farm. The full extent of the deaths and burials may never be known.

November 5, 1867 – Funeral Expenses, $10.00. Last name unclear. This Emerson.

March 2, 1869 – Receipt to I.O. McDaniel & T.C. Moore Furnishing Hammond & Family paupers House, wood, provisions and attendance—$6.00; ?? & other burial expenses Hammond—$3.00; Coffin-3.00; December 1868.

June 8, 1870 – Pay to J.C. Roper for expenses of burying Ben Mitchell, Pauper.

July 1870 – To J.C. Roper. Digging grave for Ben Mitchell Pauper, $2.50; Shrouding for the same, $5.00; making coffin for the same, $5.00; burying, $2.50.

December 3, 1870 – Receipt To J.L. Dysart” for making one coffin.

January 4, 1871 – Pay to Samuel Pitts for expenses burying Pauper Child of Lucy Rodgers.

July 22, 1871 – Receipt to W.C. Grasham to nursing Howell a Pauper from Saturday until Wednesday, 5 days a 2$ pr day—$10.00; to furnishing coffin for same $6.00; to digging grave and burrying-2.50; killed near Stilesboro on 29th April 1871.

January 18, 1872 – Order to pay Cartersville Car Factory a& B.A. $10.00 for “one coffin & box for Wm Hazel, Pauper.

September 30, 1872 – Pay to Anthony Smith for materials and making coffin for body of child of Mary Wilson.

November 8, 1872 – Receipt to J.B Britton for making a coffin (Pine Log).

Oct 29, 1872 – Pay to Wm. Goldsmith for one coffin for Freedman Pauper on Sept 10, 1872.

October 29, 1872 – Pay to Wm. Gouldsmith for one orrin for L. Gibson, Pauper on Oct 21, 1872.

December 11, 1872 – Pay to Joseph Davis to defray funeral expense for Mathew Goodson, Pauper.

May 6, 1873 – Pay to McDonald & Branton for burial of Pauper.

May 6, 1873 – Pay to Gilbert & Baxter, agts. for graves for Pauper farm.

May 6, 1873 – Pay to Wm. Goldsmith for coffins for Paupers.

September 2, 1873 – Pay to A. Robin for coffin and to Wyley Harbin for burial expenses for M.T. Hill, Pauper.

October 7, 1873 – Pay to Wn. Goldsmith for coffins for Paupers.

September 16, 1880, p2, Cartersville Express Newspaper, transcribed by Laurel Baty. Mr. W.J. Collins, superintendent of the pauper farm informs us that one of the paupers, Lucy Felton (col) died Tuesday morning. He also says the general health of the paupers is good and reports the farm in good condition. There are now sixteen paupers at the farm.”

NOTE: The Farm records reveal that 116 individuals had some type of documentation during the tenure of the Bartow County Farm. We simple do not know the full extent of those who lived, were housed there, or died there.

For more information about the former Bartow County Poor Farm and Hickory Log School click here.

Sources:

- Carlton G. Etheridge, Investigative Survey Report, County Farm Cemetery, 9Br1048, Circa 1868-1945, October 2003.

- Transcribed and Compiled by Jane B. Thompson & Laurel Baty, Bartow County USGenWeb Project, Pauper Farm Records, 2007. https//gabartow.org/Pauper/pauper/Records.shtml

- Donna Coffee, Etowah Valley Pilgrimage, Blogging in a time of Pestilence, April 2, 2020.

- Joe F. Head, EVHS VP & Dr. Michelle Haney (Berry College), Etowah Valley Historical Society, Hickory Log School (Former County Poor Farm Property Legacy. Research Courtesy of the Etowah Valley Historical Society.

- Transcribed by Laurel Baty, The Free Press, Cartersville, Georgia, August 22, 1878, p 3.

- www.findagrave.com, Paupers Cemetery, Bartow County, Georgia.

- Matthew Gramling, A Public Health Crisis in Antebellum Bartow County, Etowah Valley Historical Society, 2020.