The Memory of the Great Locomotive Chase from Atlanta to Chattanooga

Nikolas Kekel

Abstract

The Great Locomotive Chase is a prominent feature of the interpretive landscape in North Georgia. This paper examines the cause of the Chase’s popularity as well as how public historians have used the Chase for educational purposes. In addition, this piece explores museum exhibits as academic works and acknowledging the biases of curators as their authors. Sites, museums, and organizations examined are the Atlanta History Center, Marietta Museum of History, Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, Etowah Valley Historical Society, Adairsville Visitor Center and Museum, Tunnel Hill Museum, the Chattanooga National Cemetery, several historic markers, and other public displays related to the Great Locomotive Chase.

The Great Locomotive Chase of 1862, abbreviated to GLC or simply the Chase, is a prominent fixture of the historic landscape in North Georgia. The path that Andrews’ Raiders took is now dotted with historic markers and museums that tell the story of the Chase. The story of the Chase itself is well documented and those interested in it will find sources such as firsthand accounts from the likes of William Pittenger, as well as narrative histories like Russell Bonds’ book Stealing the General. What is lacking is an examination of the way the Chase has been interpreted at places like museums. If one were to travel along the path that the General took toward Chattanooga one would find 9 roadside markers, 5 museum exhibits, 3 public displays, and a festival, all dedicated to the GLC. This begs the question, why is the Chase such a popular story? The answer of course is complex, but the most fundamental reason for the GLC’s continued popularity is its ability to adapt to the needs of the storyteller.[2]

Historians and museum curators are alike in that they are both storytellers. Every article written or exhibit constructed has a purpose other than relaying basic information such as statistics or dates. There is a message being conveyed beyond the subject at hand and this message is influenced not only by the creator’s conscious choices, but also their inherent biases. Museums and other public historical sites are often rated by the public as trustworthy sources of information and are often seen as being unbiased.[3] This is a common misconception about museums and their exhibits, for in actuality museum exhibits are created with clear goals in mind. Much like a written essay, text in an exhibit is trying to convince the reader of a certain point and is not simply a statements of fact. What does separate a museum exhibit from an essay, is the use of artifacts and interactive elements. Exhibits are also created for a broader audience than most essays are. Exhibits have to appeal to, and be digestible by, children of various ages and the adults who accompany them. As such, most exhibit text uses simple language and keeps the overall length of text short. A popular saying among public historians is that museum text is the Twitter of the academic world, keep it 280 characters or less. If text is too long or complicated visitors simply won’t read it. This environment incentivizes short and direct passages which in turn give the reader the perception of being unbiased. A curator’s intent is less obvious in any one specific passage, but becomes clear when the exhibit is taken as a whole and the way an event is framed is taken into account. Historical markers and other small public displays take this approach to the extreme, boiling down an entire event into a single paragraph of text. Word choice in such a monument is extremely important, and what is left unsaid can help reveal the author’s intent.[4]

It is important to examine museums and public displays because the majority of people would rather visit a museum than read an academic paper. Museums in America have become an arm of the education system by partnering with schools for tours. They are also one of the main ways adults learn about history once they graduate high school.[5] As such, evaluating the exhibits at a museum should be approached in a similar manner to an academic essay. The exhibit’s thesis analyzed, supporting evidence weighed, and its bias recognized.

Before looking into the markers, museums, and displays along the Raider’s path it is important to have a cursory knowledge of the GLC. The Chase took place on April 12, 1962, and involved twenty-two U.S. soldiers and two civilians infiltrating Confederate lines and stealing a train named the General. The leader of this group was named James Andrews, and after the GLC this group would be known as Andrews’ Raiders. The Raid was planned by Andrews and Brigadier General Ormsby Mitchel, commander of the Department of Ohio. The two men planned for the Raid to coincide with Mitchel’s attack on Chattanooga so that the destruction caused by the Raiders would make sending reinforcements north difficult. Two of Andrews’ men were detained and forced to join the Confederate Army, two more overslept and missed the departure of the General from Marietta. The remaining eighteen men boarded the train at Marietta, then when the General was stopped for breakfast in Big Shanty the Raiders detached the passenger cars and stole the train. Their plan was to take the stolen train north toward Chattanooga, Tennessee destroying bridges, parts of the railroad, and telegraph lines along the way. Both the attack on Chattanooga and the Raid would ultimately fail to have a significant impact on the outcome of the War.[6]

The Raiders were unable to cause sufficient destruction to the railroad to make pursuit impossible. William Fuller, the conductor of the stolen General, gave chase after the Raiders, first on foot then by commandeering the trains Yonah, William R. Smith, and Texas respectively. Fuller eventually caught up with the Raiders just north of Ringgold Georgia. After they ran out of fuel they abandoned the General and attempted to escape on foot. All 22, including the four who missed the Raid, of the fleeing raiders were eventually caught and tried in Chattanooga. Eight of the Raiders, including Andrews himself, were hanged in Atlanta, Georgia. Of the other 14 Raiders, eight escaped and the other six were later returned to the U.S. as part of a prisoner exchange. The surviving Raiders would be the first to receive the newly created Medal of Honor for their part in the GLC. All but three of the soldiers involved in the Raid would eventually receive the Medal, with those that had died receiving it posthumously.[7]

For those seeking to follow the path that the Raiders took, the most common starting place is the marker in Atlanta dedicated to those men who were executed as a result of their participation in the Raid. The marker is located at the intersection of Juniper St and Third St in downtown Atlanta, and was erected in 1952 by the Georgia Historical Commission as part of Georgia’s preparation for the centennial anniversary of the Civil War. The goal was to boost tourism by creating a historic driving trail that marked important events and troop movements during the Civil War. The marker is a logical place to start an investigation into the interpretive landscape as it is the southernmost monument dedicated to the GLC. The marker is named “James J. Andrews” and it primarily discusses him, where he was from, and his involvement in the Chase. Towards the end of the text on the marker it also mentions the other 7 men who were executed and how they received the medal of Honor.[8]

This marker is significant because it was erected as Georgia was getting ready for the Civil War Centennial and as such, it gives a small insight into that time period. The placement of the marker is also significant; it is a monument to a Northern spy placed in the heart of the former Confederacy. In his book, William Pittenger quotes Andrews as saying he would “either make it to Chattanooga or die in Dixie,” and this marker is proof that Andrews’ prediction was correct.[9] The time of construction along with its placement is indicative of a reunification mentality which in turn is a common aspect of the New South philosophy. In this context one sees Andrews not as a Union or Yankee hero but instead as an American hero, someone that everyone should be proud of. This shows that through the marker project the GHC was trying to make Georgia more attractive to Northern visitors and to boost the spirt of unification.

Though the heyday of the New South ideology was in the early 20th century with Henry Grady, markers like this one show that the spirit of the New South was still alive by 1952. After World War Two and the rapid industrialization to support the war effort, there was renewed interest in industrializing the South.[10] In the 1950s there would have been an effort to make the South more appealing to investors, just as there was during the rise of the New South in the early 20th century. With this in mind the James Andrews marker in Atlanta is part of the revival of the ideas behind the New South movement, such as a push for unification and patriotism.

The next stop along the interpretive trail is the Atlanta History Center. Located just over five miles north of the Andrews Marker at 130 West Paces Ferry Road. The Atlanta History Center started out as the Atlanta Historical Society in 1926 and became the History Center in 1990. The AHC is a large museum in downtown Atlanta with a wide range of exhibits, but the one that pertains to the GLC is their exhibit on the Texas. The Texas is a steam engine built in 1856 and was one of the trains Fuller used to pursue the Raiders in 1862. The Texas was moved to the AHC in 2017 with an exhibit featuring the locomotive opening on December 17, 2018.[11]

The exhibit at the AHC which includes the Texas does not actually focus on the GLC very much at all. Of the thirteen panels that are part of the exhibit, only three discuss the GLC with the rest focusing on the railroad industry in Georgia. The room in which the Texas is housed is dominated by the engine from the moment one steps foot into it. The first panels that a visitor encounters discuss how Atlanta was originally named Terminus and how the railways were what made Atlanta into a large city. The panels that follow continue to develop the narrative of Atlanta as a rail town and discuss the advancement of rail technology into the modern day. After this, one encounters panels discussing race and the issue of segregation in rail travel. Other panels discus how the railroad was built by different minorities such as Irish and African Americans, both free and enslaved men worked on the rail road. The exhibit continues detailing facts about the rail industry and it is not until the last set of panels before you board the Texas that the GLC and the Texas are even mentioned. One panel discusses what happened to the Texas from 1907-2015, the Chase itself is given one panel, and a third panel details the Chase’s impact on culture through movies. There is a final set of panels in front of the Texas which discuss the various parts of the train along with the modifications and restorations it has endured through its existence.[12]

The choice to focus not on the GLC but instead on Atlanta as an early railroad hub is not a bad one, but is important to note that it was a decision made on the part of the curator at AHC. The Texas is most famous for its part in the Chase but had a long service career unrelated to the Chase. The exhibit examines the locomotive in its entirety and uses it more as an example of a train from the mid-19th century, than as the famous train that Fuller used to chase down Andrews. This exhibit is very recent and shows the trend towards telling more inclusive stories and not focusing on what is often called “Great Man History”. By including more relatable stories like those of the average railroad worker or traveler, the content is more accessible and has a greater impact on visitors. The GLC is an amazing story which is certainly part of the reason it has become such an iconic event, but at the AHC one sees how even these grand events can be used to tell the story of the average person and relate to visitors on a more personal level.

In Spring of 2020 Dr. Gordon Jones, a curator at the AHC, gave a talk to a group of KSU students regarding the exhibits featuring the Battle of Atlanta cyclorama and the Texas, which are closely linked due to both pieces being housed together since 1927. Dr. Jones spoke about how their audience at the AHC has changed and they can no longer simply tell a story like the GLC or the Battle of Atlanta. When they were designing these exhibits they wanted to address the entire life of the artifact not just a piece of it. The Texas had a long service life and the Cyclorama had an interesting history that had very little to do with the Battle of Atlanta. Visitors to the museum have come to expect interpretation that includes stories about minorities and the working class, not just rich white men. Dr. Jones discussed how in this day and age one must be cognizant of the Lost Cause and how it has influenced the public’s perception of certain events. He impressed upon the students the importance of recognizing what their audience’s needs are and responding to those needs.[13]

This exhibit also shows how a museum’s audience shapes its design. Atlanta is a progressive and liberal city by Southern standards and an exhibit steeped in Lost Cause rhetoric which glorified the Confederacy would not be well received there. This points to the fact that unlike an article which could receive national or even international circulation, the primary audience for a museum exhibit is the community surrounding it. A curator must be attuned to the needs of their community in order to create a successful exhibit. The exhibit housing the Texas is a great example of this as it recognizes the GLC but frames it within the larger story of the railroad in Atlanta and how its development impacted the life of everyday Atlantans. This creates an exhibit which resonates much stronger within its community than one which focused on the GLC.

The next museum north of Atlanta which features an exhibit on the GLC, is the Marietta Museum of History. The MMH is housed in the historic Kennesaw House located at 1 Depot St on Marietta Square. The building was constructed in 1845 as a cotton warehouse before being turned into a Hotel by Dix Fletcher in 1855. The building also served as a hospital and morgue for the Confederate Army during the Civil War. The MMH’s connection to the GLC is that 20 of the Raiders stayed in the Fletcher Hotel the night before they boarded the General in Marietta.[14]

The exhibit at the MMH is called the Andrews’ Room and is designed to appear as a hotel room contemporary to the GLC. The focus of the exhibit is three fold, it details the Chase giving a description of the story, it honors those who died in the raid and discusses how the Raiders were the first men to receive the Medal of Honor, and it informs the reader about the history of the building itself. Unlike the AHC the connection to the Raid is not minimized but instead it is a prominent portion of the exhibit. The MMH also chooses to use this exhibit to highlight the history of the building, with panels discussing its construction, its time as a hotel, and its use as a hospital during the war. The majority of artifacts in the room also pertain to the building’s use as a hotel, with a rope bed and hotel log books being a few examples.[15]

While this exhibit differs greatly at first glance from the one at the AHC, the MMH has also chosen to use the GLC as a shuttle for another message. The message in question being how the everyday life of historical figures differed from our own. This message may seem a bit odd, but the reason for it becomes clear when one familiarizes themselves with the Georgia Standards of Excellence. One of the first social studies standards in Georgia is describing how the everyday lives of historical figures are similar to and different from everyday life in the present.[16] With this in mind, the MMH does a wonderful job of incorporating things like a chamber pot, washing bowl, and a rope bed that help young students grasp the idea that life in the past was very different to how we live our lives today. This speaks to the partnership between museums and schools, where teachers will often rely on museums to provide educational experiences that satisfy certain educational standards. The third aspect of the exhibit, informing visitors of the buildings history, also ties nicely into the themes seen thus far. As this was the place where the Raiders stayed, the building becomes an integral part of the story and just like the Texas at the AHC, the building has another story all on its own. By tying this into the GLC, visitors learn about a Marietta landmark as well as what the average person would have experienced when staying in a hotel in the 1860s.

Big shanty, now known as Kennesaw, is where the Raiders stole the General and it also features a museum dedicated to the GLC. The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History is located at 2829 Cherokee St in Kennesaw. The museum started out as the Big Shanty Museum in 1972 and as it grew and collected more materials and artifacts the name was changed several times before settling on the Southern Museum. The history of the museum is tied into the GLC as it was initially constructed to house the General after Georgia received custody of it from Chattanooga.[17] The exhibit that exists at the museum today stands in contrast with the previous examples in that it is almost wholly dedicated to the GLC from beginning to end. While the rest of the museum explores the history of the railroad in Georgia, once the exhibit on the General begins almost all panels are dedicated to some aspect of the Chase. There are even large models of the Lacey Hotel and Tunnel Hill that visitors walk through. The entire exhibit takes up several rooms with one dedicated to the men who participated in the event, one about the details of the chase with maps and photos of various parts along the path, and another dedicated to the General. It is in the final room that a second narrative is introduced. There is an interactive panel which details how after the General was decommissioned from regular service, it was restored to tour around the country as a show piece in exhibitions. There is also a short film about the General which plays every thirty minutes in a theater just before one enters the exhibit.[18]

The SMCWLH’s approach is similar to the AHC but on a museum scale rather than an exhibit scale. The General is the most famous piece of the museum’s collection but to see it visitors have to go through several exhibits on the history of the railroad and the Glover Machine Works. However, on an exhibit level it is heavily focused on the GLC to the point where one has to look for more information on the General after the Chase. From this it is clear that the SMCWLH is engaging with a different audience than the AHC. The exhibit at the Southern Museum portrays Fuller as the hero of the story. This is particularly noticeable in the short film about the Chase which ends with a toast to Fullers as a Confederate hero.

Across from the museum is the Kennesaw Depot park which showcases murals by Wilbur Kurtz, depicting highlights from the GLC. Accompanying the murals are text panels which describe the events of the Chase. The park along with the museum are examples of how the chase is part of the character of Kennesaw. Many cities base choose an identity with which to market themselves, one can see that one of the ways Kennesaw has chosen to market itself is as the start of the Great Locomotive Chase. This event has become engrained in the local narrative and is now used to generate tourism for the area. This helps to explain why the museum focuses so much on the chase, as it is a spot of pride for Kennesaw. The General is a prominent piece of local history and the Chase put Kennesaw on the map, making the name Big Shanty famous.

All along the journey to retrace the Raider’s path, one will find numerous historical markers that detail the Chase. There is of course the Andrews marker in Atlanta but there are also markers in Marietta, Kennesaw, Kingston, Tunnel Hill and Ringgold. Several of these live in what are called marker farms where several historical markers are placed in close proximity. The museum at Tunnel Hill has just such a farm outside of it, but the most noteworthy marker outside of Atlanta is the one in downtown Kennesaw. This marker gives a very brief description of the Raiders and primarily focuses on Fuller and the other Confederates that pursued the Raiders. This is noteworthy given the marker’s proximity to the Southern Museum as well as their mutual focus on Fuller.[19]

The Etowah Valley Historical Society is based out of Cartersville and recently erected a plaque along the railroad tracks in downtown Cartersville commemorating the GLC. Joe Head, a member of the EVHS, spoke about his experiences with the GLC. Head first became interested in the Chase when, as a child, he missed the General when it was visiting Georgia as part of an exhibition. This missed opportunity piqued his interest in the Chase and when he was in college he researched the then-ongoing legal battle between Georgia and Chattanooga. The Southern Museum briefly discusses this issue but Head’s research into the subject is more extensive than what is portrayed there. Head pursued his research on the General into graduate school and beyond, publishing several pieces on it. Head has given over 200 talks discussing the legal battle for the General, and has turned his childhood interest into serious academic work.[20]

Joe Head is an example of another reason for the continued importance of the GLC. The personal connection to the story inspires individuals who become champions of the story. A notorious example of this type of character is Wilbur Kurtz who, throughout the early and mid-20th century, ensured the GLC’s place in history. He created many works of art related to the Chase, he consulted on the GLC Disney film, and he advised many others on their own works. Head is a modern day example of Kurtz, as Head spread his own story about how Chattanooga attempted to steal the General for a second time and how it was returned to Georgia by the Supreme Court. This story is a product of his own research and more modern events, but it is linked to the GLC and the General and so long as he continues to proliferate it, he will keep the GLC in the public eye.[21]

After Mr. Head and Cartersville, is the Adairsville Depot Museum and Visitors Center. Located at 101 Public Square, the Depot houses a small collection of artifacts relating to Adairsville. The interpretation at the Depot was a partnership between the KSU and the City of Adairsville. Students from one of Dr. Jennifer Dickey’s Public History courses conducted research on the Depot and wrote the series of interpretive panels that now reside there. The exhibit at the Depot focuses on Adairsville history showing it from its beginnings as a Native American town, to a small railroad town which grew into a major producer of cotton and peaches. The GLC takes a prominent role in the center of the Depots exhibit with a set of model trains rigged to repeat the Chase as one reads about the event below them.[22]

The exhibit at the Depot frames the GLC as one of many significant events that happened in Adairsville while also including information about the Western & Atlantic Railroad and everyday life in Adairsville. The approach taken at the Depot appears to be a mixture of that taken at the Southern Museum and the AHC. The event is featured prominently but it is also used as a shuttle for other information about life in Adairsville and connects the viewer with more relatable experiences. Unlike previous exhibits on the matter, the depot discusses the fates of both the Texas and the General after the GLC and touches on the legal battle that surrounded the General’s return to Georgia.[23]

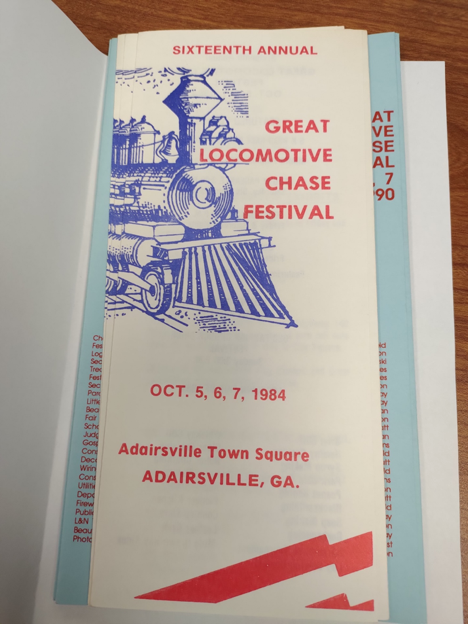

Adairsville is also the home of the GLC Festival, a three-day long event which commemorates the events of the Chase. The Festival started in 1969 and combines a carnival and a fall festival along with a celebration of Adairsville’s part in the GLC. As mentioned in the promotional material for the Festival, Adairsville was the location where Fuller met with train engineer Peter Bracken and renewed his pursuit of the Raiders aboard the Texas driving in reverse.[24] Much like in Kennesaw, the GLC has become part of the Adairsville story and is now intertwined with residents’ yearly traditions. The festival is as much a recognition of the GLC as a celebration of town’s history as a whole and way for the community to bond over a shared past, carnival rides, and fried food.[25]

Tunnel Hill as previously mentioned features several markers as well as a museum and, as the name implies, a tunnel that goes through a hill. Both the Raiders and Fuller went through the railroad tunnel which still exists as a foot path at Tunnel Hill. The museum at Tunnel Hill dedicates one display case to the GLC with the rest of the museum being about related subjects such as the Western & Atlantic Railroad and the Civil War. The interpretation at Tunnel Hill stands out for being so light. The tunnel itself lacks any kind of text panels explaining the Chase with those that are present focusing on how the tunnel was built and operated. Tunnel Hill continues the trend of using the GLC as a means to educate on a related topic, in this case the railroads and the Civil War.[26]

The final stop along the Raiders trail is a monument in the Chattanooga National Cemetery to those Raiders that were executed in Atlanta after the Chase. The monument consists of the Raiders’ graves and a large bronze casting of the General atop a stone base. The civilians James Andrews and William Campbell are buried alongside their fellow Raiders despite them not being soldiers. Upon visiting the monument, one would immediately notice the coins which decorate the tops of the Raiders’ grave stones. This is part of a military custom when visiting the grave of a fallen soldier to place a coin on top of the grave to let the family of the soldier know that you visited.[27] The large piles of coins atop the raiders graves shows how actively visited this monument still is. The monument at the National Cemetery is important because it shows that despite being over 158 years old, the events of the Chase are still impactful enough to compel numerous people to visit the graves of the Raiders and leave offerings. Clearly the stories being told and the histories written about the GLC still have a wide audience in Tennessee and North Georgia.

There have also been two movies and several books made about the GLC, the most famous of which is the 1956 Disney film by the same name. While these films and popular books, like Stealing the General, have had a large impact on the perception of the GLC, they are more national interpretations and are therefore less relevant to the interpretive landscape of North Georgia.[28]

The common denominator among all of the exhibits, markers, and monuments examined is the flexibility inherent in the GLC. It makes a compelling story which can be told in numerous ways based on the needs of the story teller. It can take the form of a pro-U.S. narrative which pushes the Raiders as the heroes of the story, as a means to boost unification sentiment and patriotism in a time when there was a push for industrialization and investment in the South. The GLC can also be used as a pro-Confederate narrative which portrays Fuller as a proud Southern hero who caught the invading Northern aggressors. Or, as is most often the case, the GLC can be used as an educational tool by public historians to educate visitors on important topics such as the history of the railroads or a commentary on race relations in a segregated South.

In closing, the interpretive landscape of North Georgia is littered with exhibits, monuments, and markers dedicated to the GLC and while all have similarities, they all approach the topic in a unique way. This is a result of them being produced by people with their own biases, who wanted to tell a certain kind of story and they used the GLC to do it. They were able to because the Chase is such a versatile narrative with numerous potential heroes and villains and it is surrounded by an important and rapidly advancing technology, the railroad. The GLC also has dedicated orators like Joe Head who have a personal connection to the Chase and continue to expose more and more people to it through the telling of their own stories. As long as historians continue to need interesting and flexible narratives to help them educate their audience, the Great Locomotive Chase will continue to stay relevant.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Exhibit text and audio tour. The Great Locomotive Chase. Tunnel Hill Museum, Tunnel Hill, Georgia.

Exhibit text panels. General History Gallery. Adairsville Rail Depot Age of Steam Museum, Adairsville, Georgia.

Exhibit text panels. Andrews’ Room. Marietta Museum of History, Marietta, Georgia.

Exhibit text panels. Locomotion. Railroads and the Making of Atlanta. Atlanta History Center, Atlanta.

Exhibit text panels. The Great Locomotive Chase. The Southern Museum of Civil War & Locomotive History, Kennesaw, Georgia.

The General in Acworth, Georgia, April 1963, Save Acworth History Foundation collection, SC/A/003, Kennesaw State University Archives.

Georgia Historical Commission. Andrews Raid, 1954. Marker. Big Shanty and the Stealing of the General, Kennesaw, Georgia. November 4, 2020.

Georgia Historical Commission. James J. Andrews, 1954. Marker. Site of James Andrews’ Execution, Atlanta. October 19, 2020.

Georgia Historical Commission. Kennesaw House, 1952. Marker. The hotel the Raiders stayed in the night before the Raid, Marietta, Georgia. September 1, 2020.

Georgia Historical Commission. The Andrews Raid at Kingston, 1953. Marker. Raiders delayed in Kinston, Kingston, Georgia. November 4, 2020.

Georgia Historical Commission. Western & Atlantic Railroad Tunnel, 1992. Marker. Construction of the first southern railroad tunnels by W&A, Tunnel Hill, Georgia. November 4, 2020.

Great Locomotive Chase Festival Collection. 1979-2017. SC-G-008. Kennesaw State University Archives, Kennesaw, Georgia.

Hamilton, William J. Jr. Script for a play titled “An Epic of the Confederacy: The Great Locomotive Chase.” 1938. PS 3515 .A4165 E64x, Box 5. Pamphlet Collection, Kennesaw State University Archives, Kennesaw, Georgia.

Monument to the first Congressional Medal of Honor recipients, 1890. Monument and inscription. Andrews’ Raiders Monument, Chattanooga, Tennessee. November 4, 2020.

Bibliography

Secondary Sources

Alexander, Mary. Museums in Motion – an Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Bonds, Russell S. Stealing the General. Yardley, Penn: Westholme, 2009.

Hackney, Sheldon. “Origins of the New South in Retrospect.” The Journal of Southern History 38, no. 2 (1972): 191-216. Accessed December 9, 2020. doi:10.2307/2206441.

Head, Joe F. “The Heart of the Chase the Great Locomotive Chase in Bartow County.” Bartow Authors Corner Civil War and Military Activity (December 16, 2015). https://evhsonline.org/archives/42894

Head, Joe F. The General: the Great Locomotive Dispute. Cartersville, GA: Bartow History Center, 1997.

Horwitz, Tony. A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World. London: J. Murray, 2008.

Horwitz, Tony. Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998.

“Grade 1 – Social Studies Georgia Standards of Excellence.” Georgia Standards. Georgia Department of Education, June 9, 2016. https://www.georgiastandards.org/Georgia-Standards/Pages/Social-Studies-Grade-1.aspx.

Kekel, Nikolas D, and Gordon Jones. Dr. Gordon Jones on the Texas and Cyclorama. Personal, March 2020.

Kekel, Nikolas D, and Joe Head. Joe Head on the Great Locomotive Chase. Personal, October 30, 2020.

Lewis, Robert. “World War II Manufacturing and the Postwar Southern Economy.” The Journal of Southern History 73, no. 4 (2007): 837-66. Accessed December 10, 2020. doi:10.2307/27649570.

“Locomotion: Railroads and the Making of Atlanta: Exhibitions.” Locomotion. Railroads and the Making of Atlanta. Atlanta History Center, November 21, 2020. https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/exhibitions/locomotion-railroads-and-the-making-of-atlanta/.

“Museum History.” Southern Museum. The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, 2020. https://www.southernmuseum.org/about-copy.

O’Connell, David. The Art and Life of Atlanta Artist Wilbur G. Kurtz Inspired by Southern History. Charleston: The History Press, 2013.

Parker, Randy. “Head Helps Preserve Bartow’s Past for Future Generations.” The Daily Tribune News. April 21, 2018, E- edition, sec. Bartow Bio. https://daily-tribune.com/stories/head-helps-preserve-bartows-past-for-future-generations,18598

Reid, Peter. “The Meaning behind the Tradition of Leaving Coins on Veterans’ Gravestones.” American Military News, March 14, 2017. https://americanmilitarynews.com/2017/03/meaning-behind-tradition-leaving-coins-veterans-gravestones/.

Pittenger, William. Daring and Suffering: A History of the Great Railroad Adventure. Philadelphia: J.W. Daughaday, 1863.

Pittenger, William. The Great Locomotive Chase: A History of the Andrews Railroad Raid into Georgia in 1862. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Publishing Company, 1921.

Wood, Catherine. “Visitor Trust When Museums Are Not Neutral,” 2018.

[1] The General in Acworth, Georgia, April 1963, Save Acworth History Foundation collection, SC/A/003, Kennesaw State University Archives.

[2] Many Histories have been written about the GLC however few have addressed how the Chase has been remembered. Other pieces have covered different events such as Sarah Vowell’s Assassination Vacation which focuses on sites which interpret famous assassinations. And some like Tony Horwitz Confederates in the Attic have even covered the Civil War as a whole. But none of these investigative histories have covered the GLC and its impact on historic sites in North Georgia.

[3] Wood, Catherine. “Visitor Trust When Museums Are Not Neutral,” 2018.

[4] Mary Alexander, Museums in Motion – an Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

[5] Catherine Wood, “Visitor Trust When Museums Are Not Neutral,” 2018.

[6] Russell S. Bonds, Stealing the General (Yardley, Penn: Westholme, 2009).

[7] Ibid

[8] Georgia Historical Commission, James J. Andrews, 1954, Marker, Cite of James Andrews’ Execution, Atlanta. October 19, 2020.

[9] William Pittenger, The Great Locomotive Chase: A History of the Andrews Railroad Raid into Georgia in 1862, 8th ed. (Philadelphia: Penn Pub. Co., 1921) 101.

[10] Robert Lewis, “World War II Manufacturing and the Postwar Southern Economy.” The Journal of Southern History 73, no. 4 (2007): 837-66. Accessed December 10, 2020. doi:10.2307/27649570.

[11] “Locomotion: Railroads and the Making of Atlanta: Exhibitions,” Locomotion. Railroads and the Making of Atlanta. (Atlanta History Center, November 21, 2020), https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/exhibitions/locomotion-railroads-and-the-making-of-atlanta/.

[12] Exhibit text panels, Locomotion. Railroads and the Making of Atlanta, Atlanta History Center, Atlanta.

[13] Nikolas D. Kekel, and Gordon Jones, Dr. Gordon Jones on the Texas and Cyclorama, Personal, March 2020.

[14] Exhibit text panels, Andrews’ Room, Marietta Museum of History, Marietta, Georgia.

[15] Ibid

[16] “Grade 1 – Social Studies Georgia Standards of Excellence,” Georgia Standards (Georgia Department of Education, June 9, 2016), https://www.georgiastandards.org/Georgia-Standards/Pages/Social-Studies-Grade-1.aspx.

[17] “Museum History,” Southern Museum (The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, 2020), https://www.southernmuseum.org/about-copy.

[18] Exhibit text panels, the Great Locomotive Chase, the Southern Museum of Civil War & Locomotive History, Kennesaw, Georgia.

[19] Georgia Historical Commission, Andrews Raid, 1954, Marker, Big Shanty and the Stealing of the General, Kennesaw, Georgia. November 4, 2020.

[20] Nikolas D Kekel, and Joe Head., Joe Head on the Great Locomotive Chase, Personal, October 30, 2020.

[21] David O’Connell, The Art and Life of Atlanta Artist Wilbur G. Kurtz Inspired by Southern History (Charleston: The History Press, 2013).

[22] Exhibit text panels, General History Gallery, Adairsville Rail Depot Age of Steam Museum, Adairsville, Georgia.

[23] Ibid

[24] Great Locomotive Chase Festival Collection, 1979-2017. SC-G-008, Kennesaw State University Archives, Kennesaw, Georgia.

[25] Ibid

[26] Exhibit text and audio tour, The Great Locomotive Chase, Tunnel Hill Museum, Tunnel Hill, Georgia.

[27] Peter Reid, “The Meaning behind the Tradition of Leaving Coins on Veterans’ Gravestones,” American Military News, March 14, 2017, https://americanmilitarynews.com/2017/03/meaning-behind-tradition-leaving-coins-veterans-gravestones/

[28] While these films have also been influential in the way the GLC has been remembered, there are key differences between them and the sites examined in this piece. The films are designed first and foremost for entertainment and were not created to be accurate representations of the event. The other key difference is that these films are aimed at a national audience and are not reflective of the attitudes in North Georgia. Written accounts of the Chase such as Stealing the General, while more so then the films, are also not as relevant to the memory of the GLC. While these books are aimed at an audience in north Georgia, they lack a wide readership and would not be used to teach children about the Chase. Works accessible to children are important because it is these types of pieces which have the type of lasting impact that is required to sustain the high levels of interest in the GLC.