Amidst the Holly and Pine: Memories and the Meaning of Christmas in Bartow County

By Matthew Gramling

When one thinks of the Christmas season a host of memories tend to flood the mind. Usually we are drawn to a nostalgic remembrance of those traditions which have a particularly special place in our hearts. Whether it be memories of sipping eggnog by a warm hearth, decorating the Christmas tree with ornaments, or gathering around the table with friends and family for a sumptuous Christmas dinner—all of these make up the tapestry of how we remember and understand the meaning of Christmas in our respective homes and communities across the ages. Each community often has its own history and traditions when it comes to celebrating Christmas and Cartersville is no exception.

The celebration of Christmas has a long and intriguing history in Bartow County. Among the earliest recorded celebrations of Christmas in the county occurred among the Cherokee at the Moravian Oothcaloga mission station in what is now Gordon County. Since the Moravians were a German Protestant group with roots in Saxony, many of the early Christmas celebrations in Bartow County mirrored the Yuletide traditions of Southern Germany. The making of Christmas wreaths was a particularly popular tradition of Germanic origin. In 1821, the new mission leader of Springplace—Rev. J.R. Schmidt—wrote to the brothers and sisters of the congregation town of Salem in North Carolina requesting 150 Christmas wreaths be sent to the Springplace and Oothcaloga for the Yuletide season.[1]

He writes, “I almost forgot an important request. It is customary here [illegible]…Christmas Eve for the people [illegible]…are distributed. Now dear Anna Rosel, who made the [wreaths] is not here any more. Perhaps our dear Brother Van Vleck would be so good as to make a request for us in the boarding school. Perhaps the pupils will feel moved and make us about 150 wreaths for here and Oochgelogee. The Savior will bless them for this, and it brings great joy to our dear ones here.”[2]

Christmas was also a deeply religious holiday for the Moravians and their Cherokee converts. It was often marked by a number of sacred devotional activities and worship services. One such occasion occurred at Oothcaloga in 1825 at the recently completed mission house of John Gambold.[3] Over 100 people, mostly Cherokee, were in attendance to celebrate a complete Moravian Christmas Lovefeast. The lovefeast was a religious social gathering rooted in the ancient Christian Agape celebration and was first celebrated by the Moravians at the Herrnhut estate of Count Zinzendorf in 1727.[4] Hymns were sung to commemorate the birth of Christ, lighted wax tapers were passed out amidst the dimly lit room to ‘represent Christ as the light of the world,’ and at the height of the service sweet buns were distributed by the dieners (or servers) among the congregation.[5] Therefore, a convivial spirit of brotherly love and spiritual devotion permeated the Moravian-Cherokee Christmas’s of Bartow County.

After the Cherokee removal and arduous journey to the Indian Territory of Oklahoma known as the Trail of Tears, the celebration of Christmas in Cartersville took on a different cast. With the dramatic growth of the cotton economy in the Georgia Upcountry during the 1850s, Bartow County saw a considerable increase in the plantation system. A typical plantation Christmas in the backcountry of North Georgia could be an occasion of intense social excitement and activity.[6] With the southern gentry’s admiration for English custom, a plantation Christmas often reflected the great Christmas social gatherings of the Victorian English elite yet with Longleaf pine and a southern drawl.[7]

Scenes of lavish partying, feasting, playing, and even a morning (fox) hunt could be among the bustle of a plantation Christmas.[8] It was often customary that Christmas would be celebrated at the home of the family patriarch.[9] All members of the family would return to the estate of their fathers and grandfathers and spend up to a week in Christmas revelry. Homes could be filled to as many 20-40 members of the extended family.[10] Those who could not make it were often dearly pined for as is evident from a letter written by “Ma” Thompson to her daughter Caroline Elizabeth Jones of Walnut Grove.

She writes, “[Illegible] Caroline My Dear Child,

Here(?) am I today [illegible] that you and the [illegible] was here to spend Christmas with us as were are all well and in fine spirits as we have had a gayful time [at] the arrival of Thomas and Louisa.[11]

With the Victorian plantation Christmas, we begin to see the establishment of many of the traditions we associate with modern Christmas celebrations in Bartow County. Victorian celebrants sentimentalized the holiday and began to shift its emphasis away from an overtly religious holiday to more of a domestic social festival with religious elements.[12] One begins to see the widespread practice of putting up a Christmas tree, singing carols, going to Christmas balls and dances, and most notably the exchange of gifts.[13]

The growth of the plantation system in Bartow County also meant the increased presence of African slaves as well as slave Christmas traditions. A typical Christmas celebration among African-American slaves often reflected and intermingled with the activities of their masters while retaining a number of distinctive customs. While slave experience of the holidays could vary widely, most often the Christmas season represented a unique time in the daily lives of slaves. On most plantations in the South, the month of December represented a time in which work slowed to a near standstill.[14]This break in the work routine would often become a social season for slaves.[15] Christmas often meant a reprieve from the grinding toil of plantation labor since most masters did not require their slave to work during the holidays. The length of this respite often coincided with the amount of time it took for the Christmas Yule log to burn, which in some cases took up to a week.[16] Slaves would often take this opportunity to visit friends and kin on other plantations.[17]

Slave celebrations of the winter holidays were frequently filled with various entertainments such as “playing ball, wrestling, running foot-races, fiddling, dancing, [feasting] and drinking whiskey.”[18] Slaveholders would often throw elaborate open-air Christmas banquets for the whole plantation.[19] Master and slave would partake of a gastronomical scene “loaded with roasted chickens, ducks, turkeys, pigs, and maybe a wild ox, varieties of vegetables, biscuits, preserves, tarts, and pies.”[20] Drams of whiskey, bowls of eggs, and similar liquorous libations flowed freely throughout the merrymaking.[21]

The richness and relaxed discipline of the holiday often allowed slaves the opportunity to interact in a manner which would be normally prohibitive during the rest of the year.[22] Masters customarily gave their slaves presents in the form of various material goods such as winter clothes, pocket knives, tobacco, coffee, and edible delicacies like Christmas sweets.[23] And for this reason among others, Christmas was often a day when slave weddings took place.[24] These Christmas weddings could frequently be a full formal marriage celebration complete with a ceremony conducted by a minister in the mistress’ parlor and an elaborate wedding banquet.[25]

Christmas could also provide slaves with a certain degree of empowerment and inversion of master-slave roles[26] On Christmas day, the exchange of gifts from master to slave could be accompanied by a peculiar ritual—the catching of Christmas gifts.[27] Children and slaves would often hide in wait for those with the means to provide gifts then spring upon them.[28] Upon ‘capturing’ their intended target they would exclaim ‘Christmas gift’ and refuse to relinquish their captives until they received a present in return.[29] Sometimes these gifts were monetary which over time could transform this ironic annual inversion of power into real power.[30] Some slaves saved enough of their Christmas gifts in money to purchase their freedom.[31]

The holidays did not always mean an interlude of freedom from the toil and control of plantation life. For some slaves, Christmas provided the perfect opportunity for them to escape their bondage permanently.[32] With slow work schedules, the relaxed discipline of the holiday, and slaveholders off visiting kin, slaves would avail themselves of the chance to obtain their liberty.[33] As I stated earlier, it was customary for slaveholders to allow slaves to travel to visit family and friends on other plantations. Slaveholders would frequently provide slaves permission to travel via a written travel pass.[34] This practice provided slaves with an indubitable pretext upon which they could travel without being suspected of attempting escape. If questioned, an escaping slave merely had to present their travel pass and explain they were on their way to visit family.[35] Such an explanation would usually satisfy most inquirers who would then allow the slave to continue on their clandestine journey to freedom.

If physical freedom could not be obtained during the holidays, Christmas often provided slaves with an expectant hope, enduring perseverance, and sense of spiritual freedom through reflecting upon the gospel stories of the nativity and life of Christ.[36] African-American Christianity provided slaves with a reservoir of symbols and meaning from which they could draw to provide them with the strength to survive their captivity. And the Christmas holiday often bolstered this reservoir by providing a rejuvenating wellspring of sacred images and memories. At Christmas, slaves could often find solidarity and solace in the nativity narratives of Jesus lowly birth in a manager, his life as the suffering Messiah, and triumph as the resurrected Savior of the world.[37]

The events of the Civil War had considerable effects upon how the people of Bartow County would celebrate Christmas. The forms of Christmas traditions remained unchanged, but the onset of the war brought about a somber seriousness to usually jubilant merrymaking of the holiday. The privations of wartime and the constant flux of morale sapped the joy out of many a families’ Christmas in Bartow County and throughout the South. With the destruction wrought by Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign and March to the Sea, many Georgians found little to celebrate at Christmas. By the end of the war, many had lost homes, businesses, crops, livestock, and scores of kin. They also suffered hardships from a dearth of food, supplies, and communication.

With the end of the war and the beginnings of Reconstruction, Christmas would gradually reclaim its former glow. And by 1868, Bartow families had returned to celebrating the holiday in its former grandeur. Writing for the Christmas edition of the Cartersville Express, Editor Samuel H. Smith addressed his subscribers with felicitations filled with a Dickensian Christmas charm.

He writes, “Christmas Eve has rolled around with it songs of mirth and its holiday stories and amusements. See at the number of tiny stockings that hang upon the bedposts and doorknob, and around the hearthstone ready to receive the deposit of good things the sage old visitor Santa Claus, is expected to make in his annual round to the young folks at home. Ah! Listen early in the morning as the gleeful shouts that arise from a thousand little tongues, when the contents of these stockings are revealed. But hark! What noise is that heard in an adjoining room? Why that merry laugh, beating and stirring and jingling of glass-ware and spoons? The question is reiterated, why? Let those who can answer! Methinks some one said, “Them’s the old folks drinking egg nogg!” Ah? Yes![38]

By the 1880s and 90s we begin to see Christmas taking on the form of a major commercial holiday in Bartow. Newspapers begin to be filled with advertisements from local businesses announcing their Christmas wares and bidding their patrons Christmas greetings. In the December 20, 1883 issue of the Cartersville Free Press, Harris Best store placed an ad declaring their great deals on Christmas treats and cooking ingredients. Fruits, nuts, cheese, chocolate and other delicacies were available and on sale for the holidays.[39]

Roughly contemporary with the commercialization of Christmas in Bartow, we see a marked growth in Christmas as an occasion for formal religious philanthropy. Churches and religious figures throughout the county would undertake various charitable activities on the holiday. One popular form of charity was to throw a public Christmas dinner for various members of the community. One charitable Christmas dinner of particular note can be found in the December 23, 1897 issue of the Courant-American wherein an announcement that the Rev. Sam Jones would be throwing a splendid Christmas dinner for the young men of Cartersville.[40] As many 125 young men were said to have accepted the invitation.[41]

With the turn of the century Santa Claus begins to appear as a staple in newspaper Christmas ads in the county. The Calhoun Brothers store posted an aid in the 1907 Christmas issue of the Cartersville News with an illustration of Santa carrying a sack of delicious Christmas goods like hams, turkeys, and cakes.[42]

With the onset of the First World War, Bartow County Christmas celebrations underwent another period of solemnity and relative privation. America’s involvement in WWI first as a provider of war supplies to the Allies and then as an Allied combatant ushered in an era of strict rationing across the nation. It also became common to bolster morale and raise donations for the war effort through patriotic holiday pageants. During the Christmas of 1917, the Bartow Red Cross chapter put on a Christmas pageant in support of local doughboys and to raise funds to provide aid to Allied refugee and wounded soldiers.[43]

During the first decade after the war, Bartow County shared in much of the prosperity that typified the roaring 20s. Yet, this would have an abrupt decline with the stock market crash of 1929. County residents were not deterred by the financial slump and were determined to support economic renewal and traditional Christmas cheer by still going out and doing their local Christmas shopping. For the Christmas season of 1929 The Tribune News reports that holiday buying in Cartersville was in full swing.[44]

With the implementation of the New Deal in 1930s, Bartow County residents’ confidence in the economy would continue to grow and they would continue to exercise that confidence in their Christmas shopping. For the holiday season of 1933, the Stewart Brothers store in Atco posted an ad in the Bartow Herald announcing an assortment of ‘holiday food values.’[45] The ad featured a portly Santa Claus carrying a sack full of Christmas foodstuff and surrounded by prices for everything from turkeys to cranberries.[46] Prices were advertised as low as 10 cents per lb. for a whole Christmas ham. Try getting that kind of deal at Publix today.

With the start of American involvement in WWII in 1941, residents of Bartow once again experienced the restraints of rationing. Despites this, Christmas in the county had been firmly established as a fully commercialized holiday and Christmas shopping continued with fervor. Even though the US entered the war on December 8, Bartow County shoppers would not allow that to put a dent into their holiday buying. For its Christmas Eve issue the Bartow Herald reports that the Yuletide season was in full swing.[47] The issue is full of Christmas ads from local businesses. There is even an ad for old Knights Mercantile wishing their patrons Christmas greetings and encouraging local shoppers to come by and do their Christmas shopping.[48]

Amidst all this holiday shopping and commerce, Christmas did not totally lose its religious significance in the county. Churches would host Christmas pageants, worship services, and parties throughout the holiday. Sam Jones Methodist Church and First Presbyterian would rehearse dutifully during the weeks leading up to Christmas.[49] Most pageants were held on the Sunday before Christmas or Christmas Eve night.[50] Christmas dances and caroling were often part of local church celebrations of the holiday.[51]

And from the 1940s to about the early 1980s it was customary for the local paper to include a Christmas reflection or lesson by a prominent local pastor in their holiday issues. Among the most regular contributors were pastors of Gilmer Street Baptist Church such as Rev. Smith and Rev. Jesse Wright.[52]

Also, during this time we begin to see the town decorated in ornate Christmas lights. Most notably, every December Main Street becomes illumined with lighted Christmas symbols and the Bethlehem Star is lit on smokestack of Chemical Products Corporation.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Christmas holiday would continue to grow as a commercial and social holiday in Cartersville. The society pages of the local paper would often be filled with reports and gossip about former residents returning home to Cartersville for Christmas.[53] The Christmas dinners and dances of prominent Cartersville families would also be announced to the potential curiosity or envy of the local reader.

The celebrations of civic clubs and organizations were also of local interest during this time. One particularly amusing revel was the 1966 Kiwanis Club Ladies’ Night Christmas party in which the husbands of members donned hula skirts and other Hawaiian attire in a scene reminiscent of Gilligan’s Island in drag.[54]

Santa Claus was also a staple of the Christmas holiday in Cartersville throughout the twentieth century. Letters to Santa from children all over the county filled columns of the holiday newspapers. They are replete with children’s addresses to Santa describing their good behavior over the last year and petitions for various Christmas gifts for themselves and their families.[55]Editors would also write addresses to local children about Santa Claus. One particularly quaint piece from the December 23, 1933 issue of the Bartow Herald is entitled “Yes, Virginia There is a Santa Claus” wherein the author addresses a child assuring her of the existence of Santa and the foolishness of her classmates nay-saying.[56]

Santa Claus would also visit disadvantaged and sick children in various places throughout the county. On Christmas of 1975, Santa Claus visited and passed out presents to a number of sick children and the local hospital.[57]

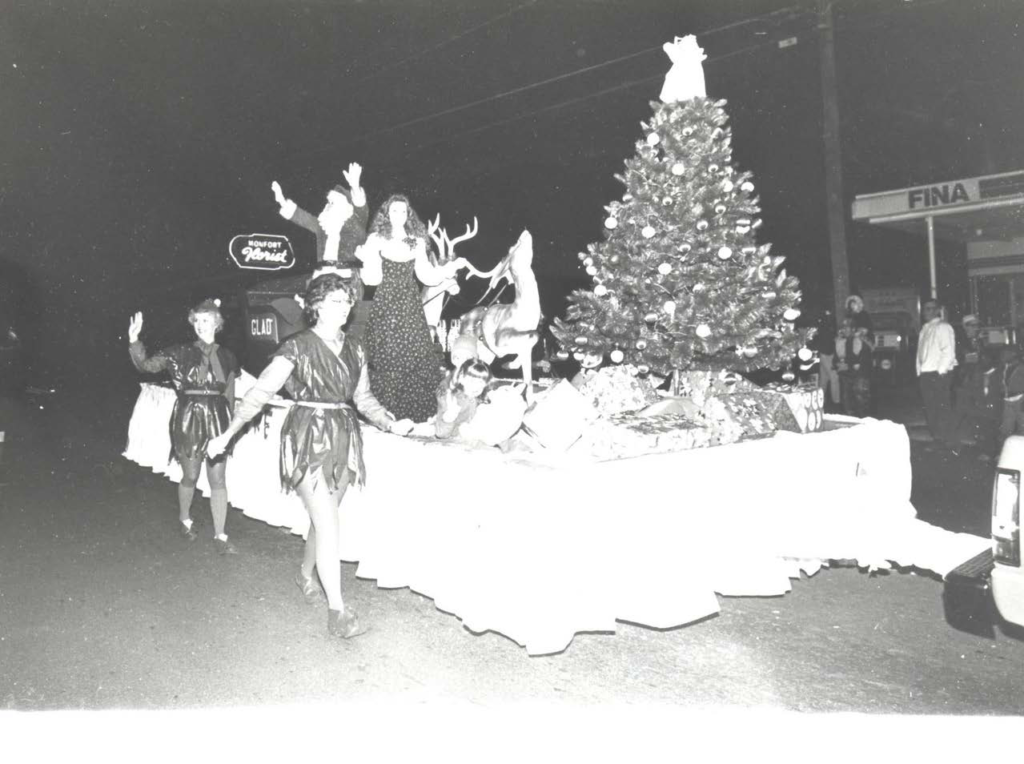

More recent holiday traditions which have become staples of a modern Bartow Christmas include: the Budweiser Clydesdales at the annual Cartersville Christmas parade, holiday decoration of storefronts around downtown Cartersville such as the Santa display at Young Brothers Pharmacy, and Christmas concerts at the Grand Theatre such the Atlanta Pops holiday concert.

The history of Christmas in Bartow County shimmers like tinsel with the radiant light of Yuletide traditions past and present, representing the folk and folkways of those who have called the county home and celebrated Christmas in it for the last two centuries. These traditions represent the richness and vitality of the holiday season in Bartow County and embody invaluable threads in the tapestry of its unique Christmas heritage. Accordingly, the author would like to wish the readers from across the county a….

Ulihelisdi Unadetiyisgv’i! (Cherokee)

Frohe Weihnachten! (German)

Merry Christmas! (English)

[1] Nancy Smith Thomas, Moravian Christmas in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 26.

[2] Thomas, Moravian Christmas in the South, 23.

[3] Edmund Schwarze, History of the Moravian Missions Among Southern Indian Tribes of the United States (Bethlehem: Times Publishing Company, 1923), 162 .

[4] Thomas, Moravian Christmas in the South, 126 .

[5] Thomas, Moravian Christmas in the South, 126-127 .

[6] Allen Cabaniss, “Christmas,” in The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. Charles Reagan Wilson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 4:210.

[7] Penne L. Restad, Christmas in America: A History(New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 76.

[8] Cabaniss, “Christmas,” 210

[9] Anne Sinkler Whaley LeClerq,An Antebellum Plantation Household:Including the South Carolina Low Country Receipts and Remedies of Emily Wharton Sinkler (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 35.

[10] LeClerq, An Antebellum Plantation Household, 34.

[11] Ma & Mary Thompson, “2005.36.133: Ma & Mary Thompson to Caroline Elizabeth Jones, (Unknown Year) December 23 ,” Omeka at Auburn, accessed November 14, 2019, https://omeka.lib.auburn.edu/items/show/2081

[12] Cabaniss, “Christmas,” 210.

[13] Cabaniss, “Christmas,” 210.

[14] Cabannis, “Christmas,” 210-11.

[15] Cabannis, “Christmas,” 211.

[16] Cabannis, “Christmas,” 211.

[17] Cabaniss, “Christmas,” 210.

[18] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays,” Documenting the South , accessed November 14, 2019, https://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/holidays.html.

[19] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[20] Restad, Christmas in America, 82.

[21] Restad, Christmas in America, 82.

[22] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[23] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.” Restad, Christmas in America, 82.

[24] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[25] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[26] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[27] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[28] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[29] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.” Restad, Christmas in America, 80.

[30] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[31] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[32] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[33] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[34] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[35] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[36] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[37] “The Slave Experience of the Holidays.”

[38] Cartersville Express, December 25, 1868.

[39] Cartersville Free Press, December 20, 1883.

[40] Cartersville The Courant-American, December 23, 1897.

[41] Cartersville The Courant-American, December 23, 1897.

[42] Cartersville New, December 26, 1907.

[43] Bartow Tribune, December 20, 1917.

[44] The Tribune News, December 19, 1929.

[45] The Bartow Herald, December 21, 1933.

[46] The Bartow Herald, December 21, 1933.

[47] The Bartow Herald-December 24, 1941.

[48] The Bartow Herald, December 24, 1941

[49] The Bartow Herald, December 14, 1933.

[50] The Bartow Herald, December 20, 1945.

[51] The Bartow Herald, December 20, 1945.

[52] The Bartow Herald, December 22, 1955.

[53] The Bartow Herald, December 20, 1945.

[54] Weekly Tribune News, December 22, 1966.

[55] The Tribune News, December 19, 1929.

[56] The Bartow Herald, December 21, 1933.

[57] Herald Tribune, December 25, 1975.