A Public Health Crisis in Antebellum Bartow County

By Matthew Gramling

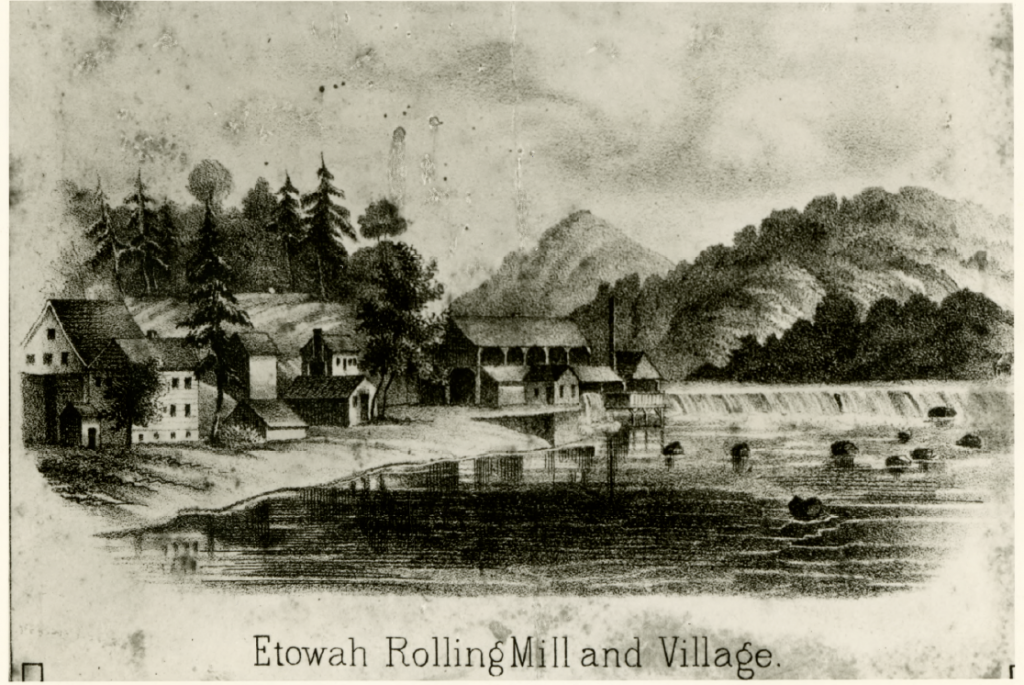

For three months in the spring of 1849, pestilence and panic gripped antebellum Bartow County. Smallpox had broken out at the Etowah Iron Works and threatened to infect the entire county unless swift action was taken to contain its spread.

News of the outbreak spread rapidly throughout the state triggering a wave of public fear which caused trade and travel throughout upper Georgia to come to a grinding halt. To meet this growing threat, municipal officials took decisive action by holding public meetings throughout the county in order to enact effective measures to prevent the disease from spreading to their communities. The sick were quarantined, temporary hospitals were established, weekly infections reports were published, and a vaccination campaign was vigorously promoted among the populace. The 1849 Smallpox Panic represents one of the first public health crises in the history of Bartow County. As such, it provides profound insight into the science and practice of southern medicine in antebellum Bartow and nineteenth-century Georgia generally. Moreover, the Panic provides an invaluable demonstration of the ways in which Bartow County residents have confronted and coped with the outbreak of infectious disease in their communities.

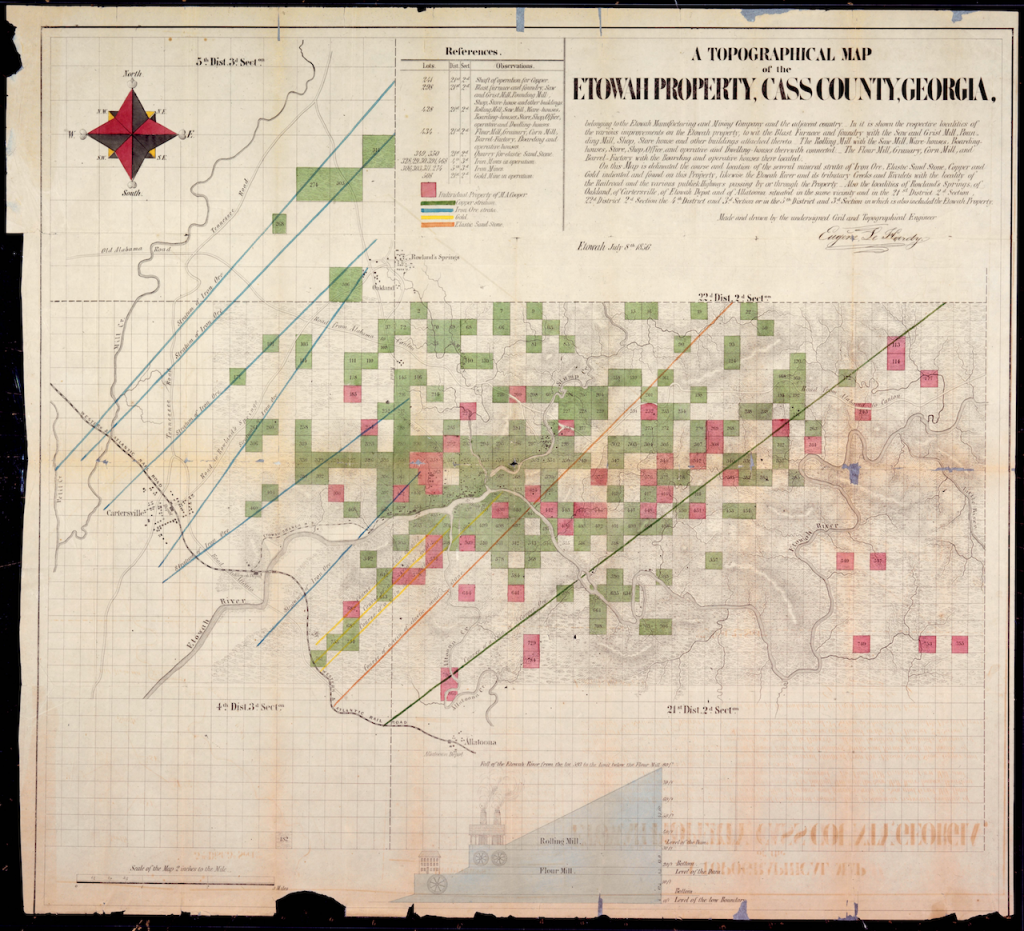

The spring of 1849 marked a dramatic episode in the lives of Cass County denizens[1]. In early March, a mysterious disease had made its appearance at the Etowah Iron Works and was generating intense public excitement among the citizens of the county. Rumors that the disease was smallpox began to circulate widely among the populace. One report from an Augusta newspaper stated that 9 cases had already occurred at there.[2] As such, Mark Anthony Cooper–co-proprietor of the Etowah Manufacturing and Mining Company– was faced with a dilemma.

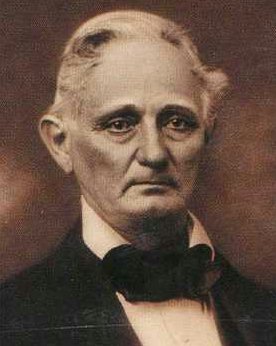

Mark Anthony Cooper

To allow such reports to go unchecked would not only jeopardize the welfare of his workers, but also threaten the health of his business. Cooper responded by writing an open letter to J.W. Burke, editor of the Cassville Standard, disconfirming the rumors that the disease was smallpox.[3] He states that while several of his children had been ill with chickenpox just six weeks prior, he can gladly say that smallpox does not exist at the Iron Works. To corroborate his report, Cooper included the medical opinion of Dr. W.H. Maltbie of Cartersville. Maltbie states that he examined three of the reported cases and of these cases he diagnosed the first as a simple case of Varicella, or chickenpox, and the latter two as being “varioloid in appearance” but lacking the hallmark characteristics of smallpox.[4] He also states he examined several similar cases in Cartersville, which turned out only to be Varicella. Thus, according to Cooper and Maltbie, the Iron Works were smallpox free. Yet, such good news proved too good to be true. For, later in the same news brief Burke included a postscript stating that just before going to press the Standard received a communication from a reputable gentleman stating that smallpox was indeed at the Iron Works and that he had heard Dr. Slaughter of Marietta convince Maltbie of his misdiagnosis. Burke closes his postscript by stating that from the sources made available to him the Standard feels compelled to inform the public that they believe it is “genuine small pox.”[5]

While public opinion quickly accepted the news that the disease at the Iron Works was smallpox, Cooper remained incredulous. In a series of letters to Burke published throughout the first two weeks of April, Cooper attempted to cast doubt on the validity of the new diagnosis even going as far to question the medical experience of the examining physicians.[6] He finally relented, albeit begrudgingly, due to the weight of public sentiment and the fact that cases began to terminate fatally. Even then he only considered it a modified or mild form of smallpox. Persuaded by Cooper’s skepticism, several prominent newspaper editors concurred with his characterization of the disease. Though as the number of cases increased and more patients succumbed to the illness, they ceased to describe it in mild terms. One fatal case deserves particular attention: Mrs. Donahoo, a young pregnant mother who was stricken with smallpox and had to deliver her child with no medical aid. Mrs. Donahoo’s husband was an Iron Works employee and when she went into labor he was suffering heavily under the effects of the disease. No medical assistance could be obtained because of the fear generated by the smallpox panic had made any nurses and physicians reluctant to attend upon patients.[7] Mrs. Donahoo successfully gave birth and appeared to be nursing well and in good health. Yet, within a week she had fallen victim to her illness.

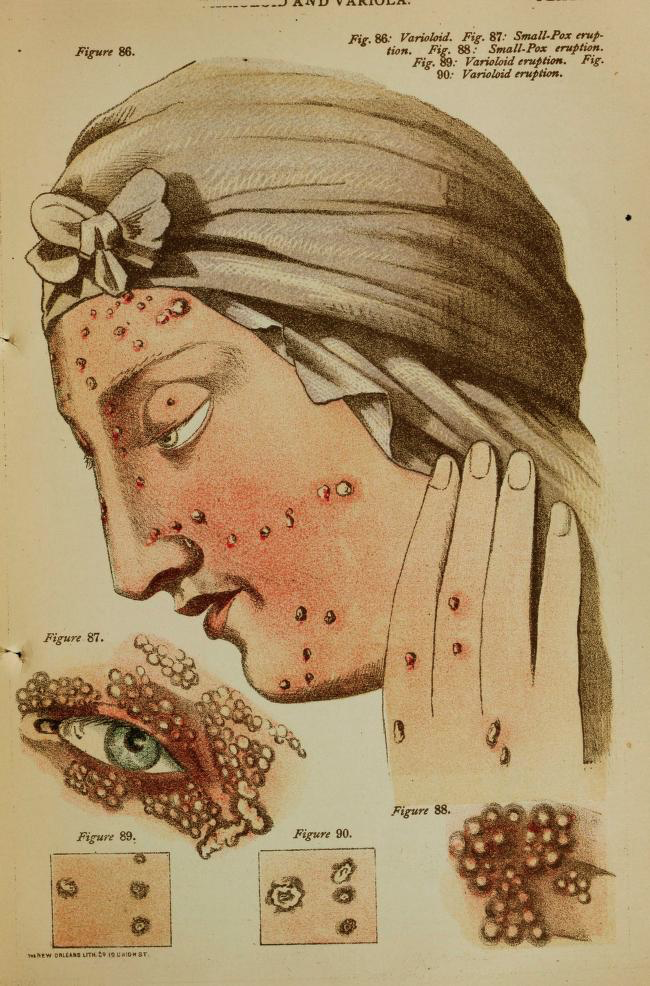

Smallpox was a dreaded and loathsome disease to antebellum Americans. A member of the orthopoxvirus family, smallpox (or Variola) was a highly infectious disease spread through direct physical contact with the sick or through inhaling the airborne saliva droplets of an infected person.[8] An individual infected with smallpox would experience high fever and a “distinctive, progressive skin rash,” which formed pea-sized pitted pustules in the epidermis.[9] These pustules would crust over forming scabs, which would eventually fall off often leaving deep pockmarks in the skin.[10] This could result in permanent disfigurement especially to the face which commonly bore the greatest number of lesions.[11] There was also a significant chance that the infected individual could be left blind from the disease.[12] And in both cases that was if the patient survived. The mortality rate for smallpox was about thirty percent.[13] Thus, it was a source of great public alarm wherever it made an appearance. There are numerous anecdotes of physicians and compassionate gentlemen undertaking the care of smallpox victims being driven forth from communities by terrified and enraged townfolk. One account relates the tragic case of a smallpox-stricken Georgia wagoner, who was obstructed in his way by local residents and forced to take shelter in a barn where he lay neglected and dying without a soul to care for him.[14] He was buried with the same concern as he was shown him in illness: the barn in which he lay dead was torched and burned down upon him by the same local denizens who had driven him thence.[15]

Simultaneous with the Iron Works outbreak, smallpox also made its appearance in Atlanta. A.M. Herring, a Florida merchant on a return trip from New York, had been exhibiting symptoms similar to smallpox when he had checked into the Atlanta Hotel.[16] He was then examined by several physicians who concluded that he had indeed contracted smallpox. News of an occurrence of smallpox in Atlanta compounded the existing alarm in northwest Georgia over the Cass County outbreak and initiated a statewide wave of rumor and panic. Erroneous reports began to circulate that smallpox was simultaneously prevailing in Macon, Augusta, Griffin, Kingston, Auraria, Marietta, Athens, and Rome, keeping local newspaper editors busy disconfirming such false reports. Some editors had to falsify rumors circulating in newspapers as far away as Montgomery and Boston.[17] In Athens, alleged smallpox reports had generated considerable anxiety and apprehension among Franklin College students and their parents.[18] As a result of this panic, travel and trade throughout the upper portion of the state came to a grinding halt especially along the route of the Western & Atlantic Railroad in northwest Georgia.[19] Smallpox rumors also had profoundly detrimental effects upon a city’s merchants whose businesses suffered greatly because travelers and patrons were apprehensive about visiting the city.[20]

In order to meet the threat of contagion and assuage public excitement, city officials had to act quickly. Preventative measures had to be established and preparations made for the care of the afflicted. With no method of treatment, most medical approaches to combating smallpox focused on preventing its introduction, inhibiting its spread, and providing for the care and comfort of the sick. Typical methods of antebellum smallpox prevention consisted of quarantining patients a safe distance outside of a community, prohibiting contact with infected locales, destruction of infected clothing, and the immediate and careful internment of the dead.[21] State law empowered city councils and county inferior court justices with the authority to establish temporary hospitals for the treatment of the sick, supply patients with the necessary subsistence and medical care (ie., nurses, etc.), and post a guard to prevent contact with the infected and their attendants.[22] At the Iron Works, Cooper and his staff attempted to implement such a policy to the best of their abilities. In order to contain the disease and expedite its departure, infected cases and those who had come in contact with them were quarantined.[23] Communion with the sick was also restricted, yet due to the lack of medical staff Cooper had to provide for their care.[24] In the case of Herring in Atlanta, he was quarantined a mile without the city at a temporary hospital.[25] The city council also passed a series of resolutions to prevent the further spread of the disease as well as took proactive measures in case it should make an appearance.They also commissioned physicians to undertake a vaccination campaign of the populace. Other municipalities throughout the state took similar preventative steps. In Cassville, local officials held a public meeting in order to enact effective policies for keeping the disease out of the town, preventing contact with infected districts, establishing temporary hospital accommodations, and ardently promoting the vaccination of its citizens.[26]

Smallpox vaccination had existed since 1796 when the English physician Edward Jenner had discovered that administering the much milder cowpox virus greatly reduced the potency and lethality of smallpox cases if not granting complete immunity to the recipient of the vaccine.[27] Vaccine matter was procured through the collection and processing of scabs, or ‘vaccine crusts,’ from the cowpox pustules of naturally or deliberately infected cows and calves.[28] Such bovine hosts provided the purest and best source for vaccine material.[29] The vaccination procedure consisted of a relatively simple operation whereby particles of vaccine matter were inserted under the skin of the arm through a prick or scratch from a small needle.[30] While usually effective, quality control of vaccine matter could sometimes be problematic.[31] In an age before modern medical storage techniques, vaccine material had a short shelf life. This caused considerable difficulties in the transportation of vaccines especially over long distances. On some occasions vaccine matter would prove entirely ineffective and thus necessitate obtaining fresh material and a readministration of vaccines. Two such occurrences took place in Cass during the panic. During the first few weeks of outbreak at the Iron Works, Mark Anthony Cooper procured a supply of vaccines for the vaccination of Etowah and its environs.[32] Unfortunately, the vaccine matter was apparently of poor quality or had degraded during shipment and thus proved ineffectual.[33] Cooper responded by making a public request to any physician with a fresh supply to send the vaccines to the Iron Works.[34] Similarly, Chief Engineer for the Western & Atlantic Railroad William L. Mitchell vaccinated his employees at the first news of smallpox in Cass County.[35] As the vaccine matter proved useless, a new supply was obtained and readminstered with positive results.[36]

Such occasions sometimes compounded any suspicion or uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of vaccination for smallpox that remained in the public mind.[37] The use of folk remedies and medicines persisted among significant portions of the population of the American South, especially Southern Appalachia.[38] Two particularly popular folk medicines used during the smallpox panic were asafetida and pine tar.[39] Asafetida was a gum or resin made from the roots of several Near Eastern plants and sold in small bags to be worn around the neck or fill the pockets of one’s garments.[40] These Asafetida bags were used as noxious, aromatic charms which were believed to ward off disease especially during the winter months.[41] The logic being that the fetid smell would keep away illness.[42] Pine tar was believed to work similarly but was smeared directly on the nose.[43] It also possessed mild antiseptic qualities.[44] Both of these folk remedies had their basis in a widely held medical belief of the time known as the miasma theory, which attributed the spread of disease due to the presence of poisonous vapors, or miasmas, caused by decomposing matter and which infected the air around a community.[45] Contemporaneous with miasma theory was the rival contagion theory, which posited that instead of illness-inducing “noxious, contaminated air” disease was caused by an infectious agent usually transmitted by direct personal contact.[46] While miasma theory was predominant throughout much of the antebellum era, by the mid-nineteenth century it was gradually being eclipsed by contagion theory. This competition and transition between two theories of disease is evident in the smallpox panic, especially at the Iron Works. In his open letters on the state of the outbreak at the Etowah Furnace, Cooper had to address speculation regarding the introduction of smallpox into the community. Rumors circulated throughout the first two weeks of the outbreak that the disease had been brought to the Iron Works by a northern or western man.[47] Cooper dismissed these reports stating, “The disease here must be of atmospheric origin, and could not have come by contagion.”[48] His dismissal of contagion and positing of “atmospheric origin” of the disease demonstrates that Cooper interpreted the opening events of the outbreak through the lens of miasma theory.Yet within a week as evidence mounted that smallpox was indeed at the Works, Cooper abandoned his miasma hypothesis and began a diligent search for the source of the contagion.[49] While the search proved fruitless it demonstrates that the events of the outbreak convinced Cooper of the credibility of contagion theory.[50]

While some elements of the population were reticent regarding the effectiveness of vaccination in smallpox prevention, many found the evidence to be conclusively in its favor. Physicians, politicians, and editors weighed heavily on the side of vaccination and encouraged the public to be vaccinated.[51] Vaccination of infected districts was even a part of official state policy in Georgia. State law mandated that the Governor was to store vaccine matter at various convenient locations throughout Georgia as well as furnish it “to the people gratis.”[52] Thus, towns and cities across the state undertook initiatives to vaccinate their residents (both black and white) free of charge.[53] During the smallpox panic, demand for vaccine matter was so high that it actually exceeded the state’s ability to effectively supply it.[54] Dr. Tomlinson Fort, one of the leading medical lights of antebellum Georgia, issued a notice in the newspapers stating that the high volume of applications for vaccine material had outstripped the state’s supply and recommended that anyone one who desired to obtain vaccine supplies should procure them from Jennerian Vaccine Institution of Maryland, “from which genuine vaccine crusts may be obtained by mail at $1 each.”[55]

In addition to promoting vaccination, boards of health were appointed by county inferior courts throughout the state to confront the smallpox threat. These, in turn, published weekly reports providing statistics regarding rates of infection, recovery, and death. In Cass County, the inferior court established a board of health chaired by Cooper himself. Weekly reports demonstrated a considerable infection rate throughout the month of April with 10-20 new cases occurring at the Iron Works every week. By the time the spread of the disease had been arrested in early May there had been 110 total cases with the five deaths at the Iron Works and three cases in Cartersville. On May 18th, the Board published its final report with the physicians of the Board giving the county a clean bill of health.[56] The concerted quarantine and vaccination efforts of the citizens of Cass and their leaders had yielded full fruition, smallpox had disappeared from the county. Shortly after, news surfaced that Atlanta was smallpox free and by the beginning of June it could be stated that the disease was present nowhere in the state. The scourge had finally run its course and for the time being the people of Cass County and upper Georgia needed not fear the ‘speckled monster.’ By the end of the summer, life had returned to a state of normalcy and merchants looked hopefully upon the prospects of good business in fall.[57] Yet, the effects of the panic were still deeply felt by some in Cass. In his annual address before a biennial session of the Georgia General Assembly in November, Governor George W. Towns brought to the attention of the legislature the great expenditure, public anxiety, and destruction to business which a portion of the citizens of Cass County had suffered during the attack of smallpox on their communities.[58] He also reminds them of the precedence set by previous legislatures in providing for the relief of such afflicted counties from the state treasury. [59] From the record it appears that due to political considerations no relief was provided.

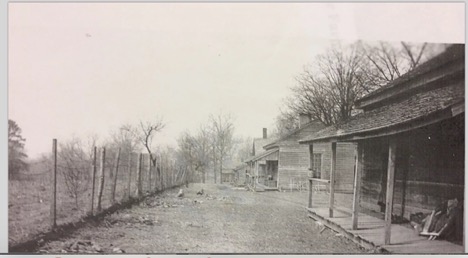

The Cass County Smallpox Panic of 1849 represents one of the most dramatic and affecting episodes in the history of public health in Bartow County. It provides a superb window into the history of medicine in antebellum Georgia and a profound demonstration of the way Cass county citizens responded to the threat of deadly contagion in their midst. During Reconstruction, county officials would establish a central quarantine and treatment facility at the Bartow County Poor Farm at what is today known as Hickory Log Personal Care Home. Smallpox cases would often be transferred to the Poor Farm where a smallpox hospital would be established for the duration of the patients’ illnesses.[60] This hospital would often be set up in one of the poor farm buildings or a special triage and quarantine tent. Nurses and physicians would be hired to care for the smallpox patients and be paid from the county treasury.[61] During the current COVID19 health crisis, pondering the history of past health crises can provide Bartow residents with a moment of pause and inspiration in reflecting upon the ways in which our forebearers suffered, coped, and persevered in the face of lethal contagion.

[1] Before 1861, Bartow went by the name of Cass County for former Secretary of War Lewis Cass. To learn more about this name change checkout the article Patriotism and Place at the Bartow Authors Corner page on the EVHS website: https://evhsonline.org/bartow-authors-corner

[2] Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel, March 26,1849.

[3] Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel, March 31, 1849. J.W. Burke was the proprietor and founding editor of Cassville Standard, which commenced publication on March 15, 1849.

[4] Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel, March 31, 1849.

[5] Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel, March 31, 1849.

[6] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 6, 1849.

[7] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 6, 1849.

[8] “Transmission,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 5, 2016), https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/transmission.html.

[9] “What Is Smallpox?,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 7, 2016), https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/about/index.html.

[10] Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Assessment of Future Scientific Needs for Live Variola Virus, “Clinical Features of Smallpox,” Assessment of Future Scientific Needs for Live Variola Virus. (U.S. National Library of Medicine, January 1, 1999), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK230904/.

[11] Institute of Medicine (US), “Clinical Features of Smallpox.”

[12] Institute of Medicine (US), “Clinical Features of Smallpox.”

[13] Bindu Tharian, “Smallpox,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, accessed October 2, 2020, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/science-medicine/smallpox.

[14] Tomlinson Fort, A Dissertation on the Practice of Medicine: Containing an Account of the Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of Diseases, and Adapted to the Use of Physicians and Families (Milledgeville, GA: Printed at the Federal Union Office, 1849), 164.

[15]Fort, A Dissertation on the Practice of Medicine, 164.

[16] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, April 05, 1849.

[17] .Richards’ Weekly Gazette, May 5, 1849. Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel, May 11, 1849

[18] Southern Banner, May 17, 1849.

[19] Chief Engineer’s Report, Western and Atlantic Railroad, 1849. Officers’ Annual Reports, Western and Atlantic Railroad, RG 18-2-72, Georgia Archives.

[20] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, May 7, 1849. Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, May 20, 1849.

[21] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 25, 1849.

[22] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 25, 1849.

[23]Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 15, 1849.

[24]Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 15, 1849.

[25]Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, May 5, 1849. Herring would later expire from his illness, but not before infecting his attendants: two whites and 3 blacks.

[26] Southern Literary Gazette, April 21, 1849.

[27] John E. Murray, The Charleston Orphan House: Children’s Lives in the First Public Orphanage in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 116. Mary Hilpertshauer, Personal communication to the author, 0ctober 2,2020. The discovery of the smallpox vaccine by Edward Jenner represents the development of the world’s first vaccine. As such, Jenner is appropriately considered the ‘father of immunology.’ I would like to thank Mary Hilpertshauer- Historical Collections Manager at the David J. Sencer CDC Museum- for her vital expertise and assistance throughout the research process of this article.

[28] Terry Reimer, “Smallpox and Vaccination in the Civil War,” September 19, 2017, https://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/small_pox/. Mary Hilpertshauer, Personal communication to the author, 0ctober 2,2020.

[29] Reimer, “Smallpox and Vaccination in the Civil War.”

[30]Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, April 03, 1849. Mary Hilpertshauer, Personal communication to the author, 0ctober 2,2020.

[31] Mary Hilpertshauer, Personal communication to the author, September 8, 2020.

[32] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 15, 1849

[33] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 15, 1849

[34] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 15, 1849

[35] Chief Engineer’s Report, Western and Atlantic Railroad, 1849, 2.

[36] Chief Engineer’s Report, Western and Atlantic Railroad, 1849, 2.

[37] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, April 03, 1849.

[38] Anthony P. Cavender, Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 71.

[39] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, May 7, 1849.

[40] “Asafetida Bags,” Asafetida Bags | North Carolina Ghosts, accessed October 18, 2020, https://northcarolinaghosts.com/folk-magic/asafetida-bags/. “Asafetida,” Ozark Healing Traditions, accessed October 19, 2020, https://www.ozarkhealing.com/asafetida.html. Cavender, Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia, 71.

[41] “Asafetida Bags.”

[42] “Asafetida.”

[43] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, April 03, 1849.

[44] Wayne Bethard, Lotions, Potions, and Deadly Elixirs: Frontier Medicine in the American West (Lanham, MD: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 2013), 9.

[45] Lois N. Magner, A History of Medicine (New York: M. Dekker, 1992), 259.

[46] Magner, A History of Medicine, 305. Contagion theory would provide the basis from which modern germ theory would eventually develop.

[47] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 6, 1849.

[48] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 6, 1849.

[49] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 6, 1849.

[50] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 6, 1849.

[51] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, April 03, 1849.

[52] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 25, 1849.

[53] The Southern Whig, May 03, 1849.

[54] Georgia Journal and Messenger, May 02, 1849. Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, April 3, 1849.Southern Recorder, April 10, 1849. The Savannah Georgian, April 07, 1849.

[55] Georgia Journal and Messenger, May 02, 1849.

[56] Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, May 18, 1849.

[57] Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, May 23, 1849

[58]Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia at a Biennial Session of the General Assembly, 1849/1850 (Milledgeville: Richard M. Orme, State Printer, 1849), 32.

[59] Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia, 32.

[60] Head, Joe, and Michelle Haney. “Hickory Log School (Former County Poor Farm Property Legacy).” Etowah Valley Historical Society. Accessed October 7, 2020. https://evhsonline.org/hickory-log-school-former-county-poor-farm-property. “Pauper Farm Records.” Accessed October 7, 2020. https://gabartow.org/Pauper/pauper.Records.shtml.

[61] “Pauper Farm Records.” Accessed October 7, 2020. https://gabartow.org/Pauper/pauper.Records.shtml.