By Joel Sneed

Bringing to Light Early Burials in Bartow County

Evidence of Native American usage has been found in twelve Bartow County caves or in the area immediately adjacent to the cave entrance. Artifacts dating from the Archaic to the late Mississippian demonstrate that Native Americans have consistently made use of the caves in this area throughout their history.

Perhaps the most common use made by the Native Americans here was for shelter, whether semi-permanent or only temporary, as during hunting trips. None of the caves were conducive to long-term habitation, but the entrance areas of a few, most notably Kingston Saltpeter Cave, Raines’ Cave, Yarbrough Cave, and Jolley Cave, would have provided shelter. In all of these caves projectile points or flakes have been found.

The most intriguing use of caves by the Native Americans and potentially the most significant was their use as mortuaries. According to Walthall and DeJarnette (1974), “…a complex of burial caves exists, or existed, in northwestern Georgia in and around Bartow County.” However, destruction of caves, looting, and improperly documented work by researchers has caused much of the scientific value of the caves to be diminished.

Of the thirty-eight known caves in Bartow County six contain or contained Native American burials. Following is a discussion of these burial caves.

Bradford Cave

Ten years ago Mr. Henson was rabbit hunting on a creek that runs through Mr. Tom McHugh’s land. The rabbit disappeared through a small hole, which evidently opened into a cave. The hole was large enough for a small hound to pass through, but barely. Mr. Henson realized that the hound was in a cave by the sound of his barking. The incident was entirely forgotten until three years ago. Then Mr. Monk Henson and Mr. John Quintin were passing that way, remembering the hole, examined the place. They found that an opening to the cave had been sealed up with rocks, very cunningly and carefully laid. It was only by pulling at them that they found that this was the work of men. And they were able to pull all the rock out and leave a round hole about four feet in diameter. The chamber within was about ten by eight feet, but was practically filled with topsoil. And Mr. Henson pulled a bone out of it, which proved to be the thighbone of a man.

This was the beginning of a mad rush to the cave, a search with picks and shovels for gold. Numerous skeletons were found, beads, copper earrings, and copper breast plates, a four legged clay pot, and many other things were found (Harris, 1950).

So read a description, written in 1934, of the discovery and looting of the cave now listed in the files of the Georgia Speleological Society as Bradford Cave, GSS 177. Known variously as Pine Indian Cave (Harris, 1950) and Pine Log Cave (Walthall and DeJarnette, 1974; Walthall, 1980), the cave is officially listed with the State Archaeologist as Corra Harris Cave and designated as archaeological site number 9BR199 (formerly BR154). The Pine Log name is due to its location near the present community of Pine Log, and the former Cherokee settlement known as Pine Log Town, both of which took their names from Pine Log Creek and its tributary, Little Pine Log Creek, which flows through the area.

Bradford Cave is formed in a small isolated knob of Cambrian age dolomite of the Rome Formation, at the easternmost extremity of carbonate rocks in Bartow County. The cave consists of one small room, 24’ by 15’, and a narrow 14-foot long crawlway. After stooping to enter the cave through the 3’ high by 5’ wide entrance, one can almost stand upright, but due only to much clay fill having been removed by the vandals. Secondary deposition is lacking, and the cave is of no significance except for the archaeological record it once contained. Cressler (1997) has written that he found a tooth from there that was identified as tapir, and the tooth was subsequently turned over to this writer, but a careful search of the cave and excavated earth has revealed nothing in the way of any further Pleistocene-age remains. Several animal bones and teeth recovered represent opossum, snake, turtle, various rodents, and rabbit, all probably Holocene.

When Mrs. Corra Harris, a novelist living in the Pine Log community, heard of the cave and of the finds there, she realized that the site was of important cultural significance, and she sought to protect it. Simultaneous with her learning of the discovery, Dr. Warren K. Moorhead, an archaeologist from Massachusetts who was conducting exploratory work at the Etowah Indian Mounds only a few miles away in Cartersville, also heard of it. He could have possibly given much-needed professional advice, except that Harris eyed him with suspicion; in her words Dr. Moorehead was “ravaging the Indian Mounds of Georgia”. Since he was reportedly on his way to investigate the cave site, she persuaded Mr. McHugh, the cave’s owner, to reseal the entrance with cement and rock. This was accomplished the day before Dr. Moorehead arrived, and he was thus denied entry (Harris, 1950). It is not known whether he was allowed to examine any of the human remains discarded in the ravine outside the cave, or if any of the artifacts that had been removed were ever made available to him for study. Likely, he was too engrossed with the work at the Mounds to be very concerned with this site.

It became the ardent desire of Ms. Harris and two or three others in the area both to recover and preserve the artifacts that had been looted from the cave, and to have the site investigated professionally. Initially, Emory University, in the person of one Dr. Con, took a six-month option to do so, but never raised the necessary funds. Harris noted that it was the wish of her and others that all items from the cave be assembled in one collection to be known as the Pine Log Indian Relics, or something similar; that the collection be curated at the State Capitol or somewhere in Bartow County; and that the cave be protected until it could be properly studied. Her death early the following year, however, seemingly brought an end to the efforts to preserve what remained of this important cave burial site. It is not certain exactly when, but at some time after her writing the cave was reopened and excavation was undertaken in the smaller passage. This area, which also contained Native American remains and artifacts, had been left untouched during the initial looting due to bad air, and a large stone had blocked access to that passage (Harris, 1950).

Harris acquired some of the artifacts that had been looted from the main chamber, by gift and purchase. One such purchase was a ceramic pot, sold to her by Everett Henson (Paul Nally, personal communication, 2001). In 1950 her heirs presented the collection to the University of Georgia’s Department of Archaeology, and they were put on exhibit that year in the Georgia Museum of Art at the University. The artifacts, referred to as the Corra Harris Collection, were later described as follows: two copper reels; two bi-cymbal copper ear spools; a dozen or more rolled copper beads, short cylindrical and ball types; a half dozen or more large garnets; scattered pieces of sheet mica; a galena cube; fragments of graphite and ocher; several two-holed quartzitic or steatite bar gorgets; and a small pottery vessel, a plain, grit-tempered bowl with tetrapod supports (Kelly, 1950). Other artifacts taken from the cave by locals in the 1930s, and which can no longer be accounted for, include “several buckets of arrowheads” collected by Weldon Roberts, and a large piece of skull removed by Willis and Hugh Bradford (Paul Nally, personal communication, 2001). It has been reported that Pine Log residents at the time of the collecting frenzy in the 1930s took buckets of dirt from the cave and sifted it in their quest for artifacts (Jodie Hill, personal communication, March 21, 2001).

In 1951, perhaps enticed by the assemblage of artifacts from the cave and by the 1934 article written by Harris, which he published the previous year as editor of Early Georgia, Dr. A.R. Kelly, head of the Department of Archaeology at UGA, conducted a summer field school in archaeology in Bartow County. Marilyn Pennington, at the time employed by the State of Georgia, interviewed Dr. Kelly in 1973 concerning his long career in archaeology in Georgia; from the early ‘30s through the mid-‘70s, Kelly had been involved in most archaeological work in the state. In the interview, Kelly spoke a little about that summer in Bartow County:

The summer was spent in exploring caves with their special sealed entrances, and Margaret [Margaret Clayton Russell] was with me on that deal. And these pothunters had…were going into these sealed caves and finding pottery and one hole and two hole bar gorgets and things like that, nothing very lavish, but from the information I got it must be something tied up with, oh, the sort of things that Webb [William Webb] was getting with his Copena culture. So they were going in these caves and trying to find some that hadn’t been opened….

(The caves were) very artfully sealed with special stones, which were arranged in there in a very natural manner, so if you walked along you would never suspect anything. The first one was discovered about the time I came to Georgia, ’47, ’45 along there [actually, in 1931]… so, we went to Pine Log and we were doing this Pine Log work, that’s the reason we went there. We went back into this cave and all the cave was dome shaped and about 20 by 30. We found a few more burials back in the narrow shelving part of the cave where it pinched out. No one could get there. I had one little girl named Mary Kellogg who was a graduate at Michigan, who was my technician. She was about 95 pounds and about 5 feet. She could get back there and just reach in and pull these bones out. She found some more copper beads. Well, this whole setup was evidently some sort of special sealed in burial, cave burial with burials and associations, which are very much like the sort of thing that Webb got up in Kentucky on the TVA and his Copena sand mounds. Only he had little clay sealed burials with similar copper and lead objects, that’s where Copena comes in, galena ore. Here in north Georgia, it seems instead of having sand mounds, you got sealed in burial caves. Then I had this whole season, we had explored every cave that was recorded, and I was trying to get a clue as to every one had been entered ahead of us.”

Even though Dr. Kelly told the owner of this cave that his party had made no additional finds (Tramell Bradford, personal communication, 1984), an unpublished report written by Dr. Kelly at the time proves otherwise, as he describes two burials that they found on a narrow shelf along one side of the room:

These comprised one adult and one child, secondary interments, small bundles laid on the shelf and covered with not more than six inches of red cave earth. The burial associations were meager; perforated bear tooth and a few more copper rolled beads, similar to those found by the gold hunters and by Mrs. Corra Harris.

He further stated that, among the excavated earth from the earlier looting, he recovered a half-dozen pottery sherds; one unstemmed, concave point of “copena” type; and bone fragments to include one long bone. Kelly states that the summer field camp added but little to the previous finds from Bradford Cave.

Despite the heroic attempts of Corra Harris and the others to preserve a collection of artifacts from the site, very little remains. With the assistance of Dr. David J. Hally at UGA in 1985, only a few items from the cave could be located there. These included seven copper beads, two shell beads, three projectile points, and one bear tooth pendant with drilled holes. Two index cards recorded finds from the cave. One, dated 07/07/51 and showing the aforementioned Mary Kellogg as the collector, listed two teeth and a bone of Middle Woodland age. The other, which also is from July 1951, shows Kelly as the collector and lists five bones, two teeth, one bear tooth pendant, eight copper beads, and nine pottery sherds.

A total of 582 artifacts from the cave are noted in Kellogg’s field notes, yet so little remains at UGA. Nowhere to be found were any of the important copper or stone relics or other burial furniture assembled by Harris, or the remains from the two burials that Kelly uncovered in 1951. Likewise, a pottery tetrapod collected in the cave by Joseph R. Caldwell (Kelly, 1952), who was a Smithsonian archaeologist working on the Allatoona Basin survey in 1946, has not been accounted for.

From what Kelly learned with interviews with local residents having direct knowledge of the looting of the cave, some forty individuals, representing all ages, were buried in the cave, laid in levels or tiers, over a period of time to a depth of three feet. These had been communal burials but not a mass inhumation (Kelly, 1952). Projectile points recovered by Kelly and others range in date from the Middle Archaic to the Mississippian, while ceramics seem to range from the Middle Woodland to Late Mississippian.

When Carole Sneed and this writer visited Bradford Cave in 1984 we salvaged some two dozen bone fragments – one arm bone of a child which exhibited signs of the child having had a disease – and three pieces of skull, the largest measuring 3” x 4-1/2”. Also recovered at that time was an antler section, probably used as a tool; a couple of small, cut mica sheets; a marine shell bead; and a few shell fragments. Later visits by Larry Blair and me and more recently by Alan Cressler produced a few more scattered remains. In the spoil pile immediately outside of the entrance, excavations in 2004 by this writer, Sharon Sneed, and Paul Nally, relative of the property owner, have unearthed teeth, bone and fragments of bone, some of the last remaining testifiers of the former necropolis wiped out by a combination of the 1930s looters and the work of Dr. Kelly in 1951.

All human remains removed by this writer have been re-interred in the cave. A date of 2150 +/- 30 ybp (years before the present) has been obtained by radiocarbon (AMS) dating on bone collagen recovered.

Little Beaver Cave

Little Beaver Cave is the most important of the Bartow County caves from an archaeological standpoint because it is in this cave that an undisturbed Native American burial was discovered. While burials had also been found in several other caves around the county, persons that found them were intent on robbing them of any burial goods, and the archaeological record was thus destroyed. This cave, though, was located by the author, and professional archaeologists were immediately brought in to conduct a proper investigation. The story of how the find was made and how the excavation proceeded was related in an article I wrote for a caving publication in 1986:

This past spring, while returning from north Georgia, I decided to leave the expressway and follow US 41 through Bartow County. Passing through one area of the Knox Dolomite that I had not previously checked for caves, I inquired at a house about the possibility of any caves in the area, and was directed to one a couple of miles to the east. I was told that many years ago people would canoe up into the entrance, and that the cave went all the way to the cave under the funeral home in Adairsville [Barton Cave]. Proceeding in the direction of the cave, I checked out several exposures of the dolomite, turning up nothing, but again inquired at another house and was shown the location of the entrance by the owner of the cave. He told me that in the late 1800s the entrance was larger than it is now, having been collapsed since then, and that no one ever enters the cave anymore. In the late 1960s his son dug open a crack about a hundred feet above the entrance, gaining access to the cave, and apparently made only one trip into the cave, being stopped by the water. This entrance appeared to be somewhat climbable, but, not having any equipment with me at the time, I chose to wait until another day to check it out.

On April 19th Carole [Carole Sneed] and I returned to the cave. We rigged a rope and rappelled in the 19’ drop, which put us in a small room decorated with formations long-since dead. We proceeded down a steep slope through a squeeze into a sloping room, which ended at the water’s edge. Many small logs were along the edge of the water as well as submerged in the two to three foot deep water. We found evidence of beavers and then spotted a baby beaver along the edge. Trying not to disturb him, I crawled into the water, checking for a lead, but found a total sump.

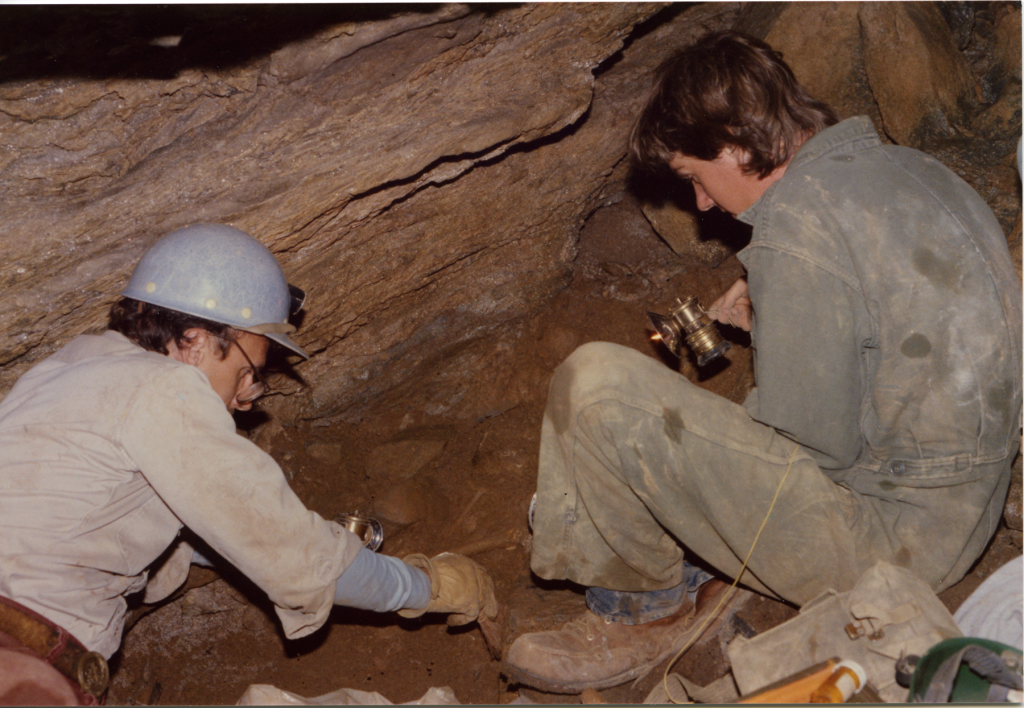

While crawling in the water on hands and knees, I spotted a tooth in the water near the bank. It was apparently human, and upon checking further I came up with another. About this time Carole had been closely examining the room, and had begun to find pieces of pottery, some of which had a stamped design. One find lead to another, and suddenly Carole came upon a larger object. As we proceeded to remove the sticky mud from around it, we began to uncover human remains, first a skull, and then leg bones and vertebrae. Realizing that we had discovered a burial, possibly another Copena site, we chose to take with us the finds that we had uncovered, after mapping their locations, and to leave the burial as-is until we could get a professional archaeologist involved.

We mapped the cave, and, upon exiting, we talked with the owner about our find, requesting that he not let others in the cave or talk about the discovery. He was interested in learning more about the burial, but stated his requirement that any excavation be performed by professionals, be limited in scope, and that following study all items removed would be reinterred in the cave.

A few days later I had the opportunity to talk with a lady that had lived on the property many years before. Her father had grown watercress in the flooded area in front of the cave, in the water that emerges from the cave, and sold it to large hotels in the North. Her father used to canoe into the entrance area of the cave, [around 1895, she postulated] which at that time had a very large arch type entrance. She said that an earthquake early in this century brought the rock arch down, nearly closing off the cave.

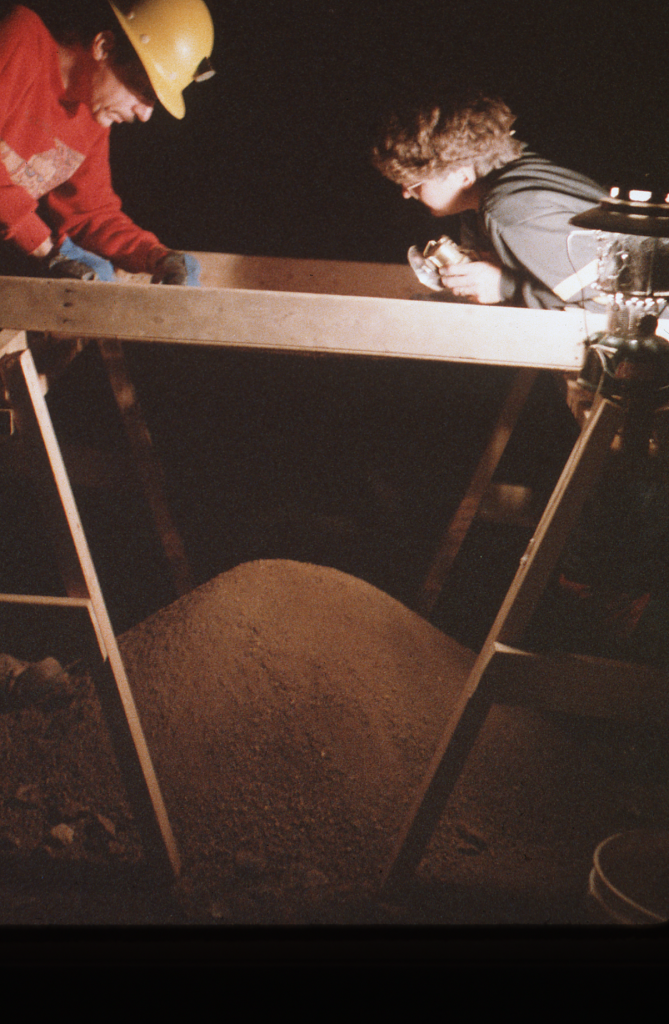

We next contacted Dr. Pat Watson at Washington University about our find, and she suggested we get Dr. P. Willey from the University of Tennessee involved in the excavation. We had known “P” from our work at Signal Light Pit [Tennessee], and he was very interested in the find. On June 28th he and Master’s candidate George Crothers met us in Adairsville, and we proceeded to the cave. We spent the entire day at the dig, removing and mapping the remains, and determined that we had at least three individuals, two adults and one child. No burial goods were found except for one item that appeared to be an atlatl (spear thrower) weight. At this time I also completed my map of the dry portion of the cave. P determined that it would be best to leave the completion of the dig for another weekend, so we covered over the site and departed.

Karl Sneed and I returned to the cave the following Wednesday, July 2nd, to complete the mapping. We surveyed overland from the upper entrance down to the water entrance, and then proceeded into the wet portion of the cave. We ran the survey as far as we could before the cave sumped, finding, upon plotting the map, that the sump is only about fifteen feet long. With the passage being so cluttered with logs, a free dive through there could be hazardous.

Now that we had a confirmed archaeological site, I completed a site registration form and sent it to the Archaeology Department at the University of Georgia. The site has now been officially registered as Archaeological Site Number 9 BR 238.

Our next trip to the site was on August 14th. P and George again came down, we were joined by Jim Greenway from the University of Georgia, and we continued our dig, uncovering many more bones, and our third skull. No burial goods were found, but we did unearth several more pottery sherds along the sloping room. These sherds include steatite and clay pottery, and have designs that are simple, corded, and complex. Also, one human hand bone was found in an alcove on the opposite side of the room from the dig. We spent ten hours in the cave, but were unable to complete the excavation, so it was decided to return the next day and either complete the dig or complete an excavation of one meter square, whichever came first.

After Carole had gone to Kingston Saltpeter Cave with Mick Harvey, a Tennessee bat expert, she joined P and George at the dig, where they had been continuing the work of the day before. A fourth skull was found, but, due to the jumble of bones encountered, it became obvious late in the evening that an end to the excavation would not be attained that day. The dig has now been closed for a few weeks until P can return.

The “few weeks” turned into months, and it was June 27, 1987 when we finally returned to the site to continue – and complete – our work there. On this trip Sherri Turner joined P, George, Carole and me in the work. P and I conducted a site survey for three hours while the others continued the excavation in the cave. On the surface – on the hill above the cave and along the creek for about a quarter mile – we found many flint flakes, a couple of point midsections, one complete Copena point, and several historical items. In the cave on this trip we completed our one-meter-square test pit and finally, in the early evening, closed down the excavation. We had found more articulated bones, bear teeth, an unidentified animal canine, and several human teeth, some exhibiting wear grooves.

The human material that was excavated was taken to the Human Osteology Laboratory at the University of Tennessee, where it was washed, reconstructed and inventoried. A synopsis of the study of the archeological material from Little Beaver Cave was presented at the annual Convention of the National Speleological Society in 1989. Following a description by this author of the site and an introduction to the study, George Crothers discussed the human context of the cave; Dr. P Willey described the excavated human remains that had been recovered and their significance; and Carole A. Sneed gave a report on the pottery found in the cave.

Since the small, vertical entrance was dug open in the 1960s, it is evident that the Native Americans had entered the cave through the stream entrance. At that time the entrance was rather large and they would have waded in a shallow stream into the room where the burials were placed. Represented in the remains of at least seven humans recovered from the one-meter square are both male and female, with ages ranging from infant, two children (3-4 years and 6-8 years), and adult; no adolescents were found. Some of the remains had been cremated, most certainly before interment in the cave, yet articulation of many of the bones indicates a primary burial, not dismembered or decomposed aboveground before burial in the cave. One of the two adult skulls unearthed showed a pronounced cradleboard flattening, a childrearing practice. With the burial having been made in the sloping floor of the room, erosion began to expose some of the bones and wash smaller items out of the deposit, eventually into the stream where the first of the teeth was found, and exposing bones to weathering and to rodent chewing.

Among the non-bone elements recovered from the cave were the atlatl weight previously mentioned, a few flaked chert pieces, and several pottery sherds, including pieces from rims, shoulder, and neck of ceramic containers. In her report presented at the 1989 Convention, Carole Sneed described and showed detail attesting to the ceramics being from the Early Mississippian Period, approximately A.D. 900 – 1200, specifically Woodstock complicated stamp and plain ware. Only one piece of pottery was cord marked, the predominate pattern of decoration being rectilinear in the form of vertical diamonds filled with horizontal lines. Among preceramics, the soapstone vessel fragments do not show any pronounced decoration nor indicate any specific time period.

Ammons’ Cave

Ammons’ Cave is typical of the small caves of Bartow County that hold a great value from a scientific standpoint, in this case one of the suites of burial caves. During the mapping of Ammons Cave, also incorrectly listed as Almond Cave, several small bones and bone fragments were recovered from the cave. Bones of a bird, rabbit, opossum, and a possible peccary toe were among the finds, but some of the material appeared to be human. On a later trip while searching for more human remains a few additional items were located, as well as the place where apparently one or more bodies had been interred. These remains were taken to the Department of Anthropology at the University of Tennessee, where they were studied by Elayne Pope. In her report, wherein she describes the material and measurements of the various elements, she has noted that represented are both adults and sub-adults. Upon return of the bones to me, I reinterred them back in the cave.

The bones we found were evidently a very small part of a sizeable burial that at one time had been in the cave, for in 1916 remains of some eighteen individuals had been unearthed by the cave’s owner, Mr. Ammons, as the following Bartow County newspaper account describes:

The cave has been known for years and for a long time has been visited by people; in fact, it was the hiding place for valuables of the country people who had valuables to secret during the civil war (sic).

There is one large room with solid rock ceiling. In the rear was a small opening just large enough for a man to crawl through.

Mr. Frank Ammons decided for the accommodation of the public he would enlarge this opening so one could walk through it instead of crawl. He was engaged in this task when he found the skull. He gave the alarm and soon enough bones were gotten together to make 18 skeletons, all apparently adults.

These bones…are now at Mr. Ammons barn. There did not seem to be any special system observed in their burial, but seemed to have been thrown in promiscuously. Two round objects were found that are about the size of large buttons with one hole in the center, also an arrow head made of flint rock, a lower jaw bone of some animal supposed to be that of a bear with one tooth that was also recovered. The bone has the appearance of having been cut with some kind of instrument.

In a telephone interview I conducted in 2001 with Mr. Dan Bowdoin, the grandson of the writer of the 1916 article, I learned that the bones had at some point been taken to Dr. Dick Bradley, in the town of Folsom. Dr. Bradley averred that the bones were, indeed, human, but he was unable to identify their race or from what period of time they lived. Dan Bowdoin, who coincidently had been delivered by Dr. Bradley, stated that his grandfather told him that the bones had been re-buried, not in the cave but in the nearby Hayes Cemetery. After talking with cemetery trustees and doing a bit of detective work, I feel that I have located the grave where the bones found their final resting place, marked with a nondescript stone.

Gin Raines Cave

Little Pine Log Creek flows northward through pastoral lands only a short distance west of the former Cherokee village of Pine Log Town. Several caves are found in the small hills along the route of the creek, but only one has yielded any evidence of the native residents of the area. Gin Raines Cave, not much more than a rock shelter, trends N52W for 80 feet. At the northern terminus, a small cave some fifteen feet in length is accessible. Continuing along the ridge beyond this feature is another small cave, Raines No. 2, six feet wide at the mouth, 25 feet in length, and trending N6E into the hillside. These caves are about six feet above the normal creek bed and flood intermittently. A few gastropods and scattered bones of a cow-sized animal were recovered from the caves.

Gin Raines Cave was one of the sites where Dr. A.R. Kelly spent time with his students in the summer of 1951, and the site has been designated Archaeological Site 9 BR 201 (formerly BR 156). While collections at the University of Georgia contain only one human specimen, a right mandible with three molars, notes there document a plethora of finds in the area around the cave that attest to a Native American presence. Listed are 88 pottery sherds, 94 flint artifacts and 3 ground stone pieces, including a stone bowl. A bead and seven projectile points were unearthed in the cave – some in an area referred to by Kelly as the “left alcove” – and one point in Raines No. 2. Dates on projectile points and ceramics show a range in usage from the Archaic through a part of the Mississippian. None of the material was to be found at UGA by this writer in the 1980s, but a more recent check records 324 artifacts located there and attributed to this site (Adams, 2007).

This cave is included with this discussion of burial caves due to the one human mandible that is extant at the University of Georgia, as well as notations about other human teeth and bone fragments that had been found. None of this material is to be found today at the university.

Ladds’ Cave

Dominating the landscape to the southwest of Cartersville is Quarry Mountain. Situated about two miles from the city center at the community of Ladds, the mountain rises some 340 feet above the surrounding countryside. Presenting itself as a scar visible for miles, this was the scene of quarrying activity for almost a century following the Civil War.

At one time there was within the mountain a magnificently decorated cavern. Twelve entrances in the quarry face and one in the floor of the quarry presently access eight remnant passages with a total of nearly 2,000 feet of passage. Although the Georgia Speleological Survey (GSS) has designated each of the separate caves with a different number, under the name Ladd’s Lime Cave, they at one time apparently comprised a single cave with one natural entrance. The existing passages along with those that were quarried away would have made Ladds’ Cave the longest in Bartow County; the range in elevation of the passages from an estimated 700 feet to 850 feet above sea level also made this the cave with the greatest vertical extent in the county. In 1972, at the request of the late Dr. Lewis Lipps of Shorter College, members of the GSS mapped the remnant cave passages along the quarry face. The eighth entrance, in the quarry floor, was discovered and mapped in 1988 by Joel, Carole, and Brian Sneed.

A Native American presence in this area over a long period of time is well documented. The Etowah Indian Mounds, built during the Mississippian period (A.D. 900-1450), are only two and a half miles from Ladds, and that is the primary site where evidence of Native Americans in the area can be seen today. But documentation has been made of a Native American presence at Ladds at an even earlier date.

Encircling the summit of the mountain at one time was an “Indian fort”, built of loose unhewn stones. Located on a terrace some 50 vertical feet below the summit, the walls were about 10 feet wide, at least three feet high, and nearly 2000 lineal feet, forming an oval and being elongated in a northeast-southwest direction. There were six entrances to the interior, measuring 10 to 60 feet in width (Whittlesay, 1883). Whittlesey, who provided a drawing of the structure, felt that it was never intended to be defensive, but rather it was the scene of public meetings, processions, or displays, the wall being merely the result of clearing the mountaintop of loose stones. The structure was located on the middle peak, at 1,057 ft. elevation the highest of the three peaks on the mountain, at about the 1,000 ft. contour. By 1936 walls existed only on the east, north, and part of the west side, approximately 1,180 feet in length, and including only two entrance openings. The stones comprising the wall had been sold to the city of Cartersville to be used in road building and by the fall of that year they were all gone.

While there is no indication of the time period in which the “fort” was constructed, there is ample evidence confirming that Native Americans were at the mountain nearly three thousand years ago. At the base of the mountain on the east side, near the confluence of Nancy and Pettit Creeks, a village site, designated archaeological site number Br-27, was occupied from the Lower Early Woodland (1,000-500 B.C.) through the Mississippian (Wauchope, 1966). Additionally, an apparent burial mound, named the Shaw Mound and designated Br-24, once existed on the southern spur of the mountain. Artifacts associated with the burials include fragments of sheet copper; several large sheets of mica that covered the face and chest of the body; a copper breastplate; two double-beveled greenstone celts; and a copper celt (Waring, 1945). A stone effigy, made from the local limestone and measuring 14 inches in height, had been plowed up in 1881 near the base of the mound (Whittlesay, 1883). The mound, which Whittlesey had described as being conical-shaped, 18 feet in height, and 160 feet in circumference, was demolished in 1940 when the property owner, Frank Shaw, became “overcome by curiosity as to the contents of the mound”, and sold the stones to the city of Cartersville for road material (Waring, 1945). Waring states that in the process of crushing rock, the copper celt was found, damaged somewhat by the crusher.

The determined age of the archaeological sites at Ladds correlates with the time frame that several caves in the area were utilized by the native population, mainly for burials. It is likely, then, that they would have made use of this cave in a similar manner. The question has arisen, though, as to whether there was, in fact, a natural, accessible entrance to the cave at that time, or whether the cave became known only through the later quarrying activity.

At one time the cave was designated as an archaeological site, Br-98, according to a card in the Archaeology Department at the University of Georgia which reads: “cave at Ladds lime works near Cartersville with entrance walled up”. Nothing was recorded about the cave; the reason for its designation as an archaeological site; or even the types of materials comprising the wall, which could give an indication of its age and purpose. The card was also undated. It could be surmised that the cave had been walled up by the Native Americans, as other burial caves had been, but a possible contradiction to this is a letter written in 1900 stating that “some years ago in developing the quarry, a cave was opened…” (Couper, 1900). However, as Couper’s letter was written in reference to some vertebrate fossils from the cave that were discovered in 1885, his wording does not rule out the possibility that it was a manmade wall that was breached at that time rather than the cave being discovered by the quarrying activity. Also, a note dated July 8, 1885 and attached to an accession card at the U.S.N.M. accompanying the fossil faunal material collected from the cave states that human bones had been removed from the same deposit. Nothing else is known about that find, but it certainly provides further affirmation of the assertion that the Native Americans were aware of, and utilized to some extent, the cave at Ladds.

One other reference that must be mentioned is an 1894 article about a suite of cave burials in the Kentucky-Tennessee-Georgia area (Thomas, 1894). The statement is made that “In Bartow county [sic], Georgia, a human skeleton was found in a cave in a limestone bluff walled in….” While not stating what cave this was nor in what part of the county it was located, Ladds among the known caves in the county is the only one that would be considered as being in a bluff. Of interest here is the statement about the entrance having been “walled in”, similar to the aforementioned card at the University of Georgia, and that, apparently from the wording, only one skeleton was found.

Kingston Saltpeter Cave

Although pottery and stone artifacts are found in abundance in this part of Bartow County, very little has been found within Kingston Saltpeter Cave. That so little has been found is not surprising in light of the intensive mining of the cave sediments for nitrates during the 1800s. This cave would have been a likely mortuary site, but tons of dirt has been removed from every area of the cave.

Stone artifacts comprise the bulk of what cultural material has been found within the cave, ceramics being totally nonexistent. In an article in the Georgia Spelunker, the newsletter of the Atlanta Georgia Grotto, reference is made to a point having been found in the cave in 1964 and another point was reportedly discovered in the cave in the summer of 1970, when local resident and artifact hunter Ronald Casey found a broken projectile point near the juncture of the small entrance passage with the Big Room. He states that he can no longer locate the point in his collection, but that he remembers it being a Woodland point (Ronald Casey, personal communication, 1988).

During the study of the cave two points and two preforms were found on the entrance slope, perhaps indicating a workshop in the cave at one time, or just that a careless early explorer dropped some of his supplies. Two limestone grinding stones have also been found, suggesting that there was a more prolonged usage of the cave than just for exploration or as a workshop. Additionally, a rounded quartz “river stone” was found, of a type of rock not found within some one hundred miles of the cave.

An archaeological survey of northern Georgia during 1938-40, conducted by the Works Progress Administration, included test pits in the cave, but produced no artifacts or other evidence of Native American usage of the cave (Wauchope, 1966), although an archaeological site designation, BR-35, was given to the site. The Kingston Saltpeter Cave Study Project in the 1980s excavated two test pits. One, in the center of the Ballroom, yielded several historical artifacts, and the other, in the passage just beyond the Ballroom a bit deeper into the cave, produced small unidentified animal bones and larger pieces of deer bone.

In addition to the cultural artifacts found in the cave, some human remains have been found. These are both meager and are either totally unidentifiable or they provide no conclusive evidence of ages of use of the cave. In the paleontological test unit described in another section, a tooth was found that appeared at first blush to be human, yet has sparked quite some controversy and debate. The tooth has been examined by many scientists across the country, with no consensus as to whether it is actually human or some unidentified animal. Physical anthropologists are almost unanimous in their belief that the tooth is not human, while biologists and paleontologists who have studied the tooth state that it matches no animal, living or extinct. It is possible that the tooth is merely a worn molar of the extinct peccary, Mylohyus nasutus, bones and teeth of which have been recovered from the same deposit. If it is, in fact, human, having been discovered in association with Pleistocene material dated to 12,700 ybp, it could be the oldest human found in this part of the country.

Another tooth found in the cave, in a drip pool in the Test Pit Room, was in an isolated area not in association with any other human or faunal material or artifacts. An interesting feature of this tooth is a groove that had been worn deeply into it.

Other than these teeth the only other human remains to be found in the cave was a left humerus from an adult female in her early twenties. This bone, exhibiting gnawing by animals and complete except for the distal end, was removed by a cave explorer in 1981. At the location in the cave where the bone was discovered – the Water Hole Room – nothing further was to be found. A radiocarbon (AMS) date of 2850 +/- 30 ybp was determined from bone collagen.

Also worthy of mention in the discussion of physical evidence of the use of this cave by Native Americans are petroglyphs drawn on the cave walls. The drawings are located near the Ballroom, which was known to have been used by the Native Americans for ceremonies, but in an area that would not be visible to the casual visitor to the cave. Due to the obscure location of the drawings they have probably eluded observation until Carole Sneed discovered them on October 26, 1982 while she was recording signatures from the cave walls. With the amount of vandalism that has occurred throughout the cave, it is fortunate that the glyphs are so well hidden, leaving a record of early visitation, though the exact time frame of the drawings is uncertain.

Discussion

For the most part, cave burials in Bartow County seem to be an extension of the Copena tradition seen across Alabama. However, with the meager data we have in regards to dates it appears that caves here, which are found in a near-perfect East-West line across the county, may have been used as mortuaries during times other than just the Middle Woodland. Indeed, of the three dates we have from burials in the county, one is Copena (Middle Woodland), while another is from the Late Archaic/Early Woodland time-frame and the other is Early Mississippian.

The record is incomplete for a variety of reasons, including removal by persons uneducated in the importance of archaeological sites, and dishonest and unethical behavior of researchers at some universities. At Ammons Cave, removal of bones long ago by local residents has rendered the site nearly useless other than documenting that burials did exist; no artifacts are known to be from there. Bradford’s Cave saw a similar excavation of remains by local residents, but we do have documentation of a wealth of artifacts removed. However, those burial goods, many of which made their way to the archaeology department at the University of Georgia, have become lost over time, by theft or otherwise.

One human mandible from Gin Raines Cave, while providing no date, is evidence of a possible burial at that site. Extensive excavation by Dr. A.R. Kelly uncovered many artifacts showing usage of the site over a period of thousands of years.

At Ladds’, it was fortuitous that a search of some of the cave passages was made prior to nearly total destruction by quarrying. Notes made of bones removed and sent to the USMN verify the existence of at least one inhumation there, but nothing more is known.

With nearly every inch of cave in Kingston Saltpeter Cave having been excavated for nitrates, whatever was once there is lost. In the dimly-lit, smoke-filled rooms and passages, any burials would have just been swept up with the earth and processed. Burial objects, had they been discovered during the mining, would likely not have been reported. The one human bone that has been found, along with a couple of teeth, may be the only remaining evidence of a former necropolis in the cave.

It is at Little Beaver Cave that the most egregious situation has occurred, where an untouched burial was found weathering out of a slope. A proper test pit was excavated by professionals and the remains found were taken to the University of Tennessee (UT) for cleaning, identification, and study. However, rather than returning the remains to the cave as the owner demanded and with which the UT staff member gave his word, the bones are being given by UT to the Cherokee Nation for interment elsewhere; the Cherokee representative handling the matter has told this writer that the bones would be placed in a hole dug in a secret location on Federal property. She and the University have refused requests to re-inter them in the cave, where the vast majority of the burials yet lie in repose. This they are doing, according to UT, as required by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). That law pertains only to finds made on tribal and Federal land, not ones made on private property as is the case here.

Funding for radiocarbon dating has been provided by the Dogwood City Grotto, Richmond Area Speleological Society, and the National Speleological Foundation.

References

Adams, Andrea E. 2007. Revisiting Arthur Kelly’s 1951 Field School and the Corra Harris Cave from Bartow County, Georgia. Early Georgia, 35(1): 71-98.

Couper, R.H. 1900. Letter to Dr. F.A. Lucas, USNM. October 16.

Harris, Corra. 1950. A Sketch of the Pine Indian Cave. Early Georgia, 1(1): 41-42.

Kelly, Arthur R. 1950. Corra Harris Collection. Early Georgia, 1(1): 44.

Sneed, Joel M. 2007. Bartow County Caves: History Underground in North Georgia.

Thomas, Cyrus. 1894. Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.: 583-584.

Waring, A.J. Jr. 1945. Hopewellian Elements in Northern Georgia. American Antiquity, 11(2): 119-120.

Wauchope, R. 1966. Archaeological Survey of Northern Georgia: With a Test for Some Cultural Hypothesis. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 21: 239-240.

Whittlesey, Charles. 1883. Miscellaneous Papers Relating to Archaeology. Smithsonian Annual Report, 1881: 624-630.

Looting of archaeological sites is a problem of major proportions, as vandals excavate and remove artifacts. When this is done and a site is disturbed in this manner, the archeological significance of the site is destroyed, lost forever. Realizing the scope of the problem, laws have been passed that provide for punishment of individuals desecrating our heritage in this manner.

In Georgia, the Cave Protection Act of 1977 makes it a crime to disturb, destroy, or remove any archaeological material found in a cave without written permission of the property owner. Federal laws, including the Archeological Resource Protection Act of 1979 and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, make it a federal crime to disturb human burials on tribal and Federal lands.