by Guy Parmenter

Many of our forefathers who endured the hardships of a time we can now only read about can still be found today resting peacefully in the numerous cemeteries which dot the landscape throughout Bartow County. Nowhere else is it possible to look so deeply into our past. A cemetery can be a wonderful world of discovery and a voyage through time, especially Cartersville’ s Oak Hill. At rest there may be found quite a few of the early settlers who have left their legacy on mankind. We have all heard of Sam Jones, the noted Methodist evangelist and Rebecca Felton, our country’s first woman United States Senator. There are Charles H. Smith, alias Bill Arp, Mark A. Cooper, the ”Iron King” of Georgia, Pierce Manning Butler Young, the youngest major general in the Confederate Army and many other notable and interesting people.

Today I write about one of these pioneers, a man with very impressive credentials inscribed upon a monument at his grave. He is a lesser known person to today’s generation. However, in his time, this individual was a man of national prominence. His legacy would be one of honesty, integrity and a defender of human rights. Welcome Amos Tappen Akerman to the list of growing memories of our past. Inscribed upon that monument is his epitaph, which reads as follows:

In Thought Clear And Strong,

In Purpose Pure And Elevated,

In Moral Courage Invincible,

He Lived Loyal To His Convictions

Avouring Them With Candor,

And Supporting Them With Firmness.

A Friend Of Humanity,

In His Zeal To Serve Others,

He Shrank From No Peril To Himself,

He Was Able, Faithful, True!

These are very intriguing words left by a loving family.

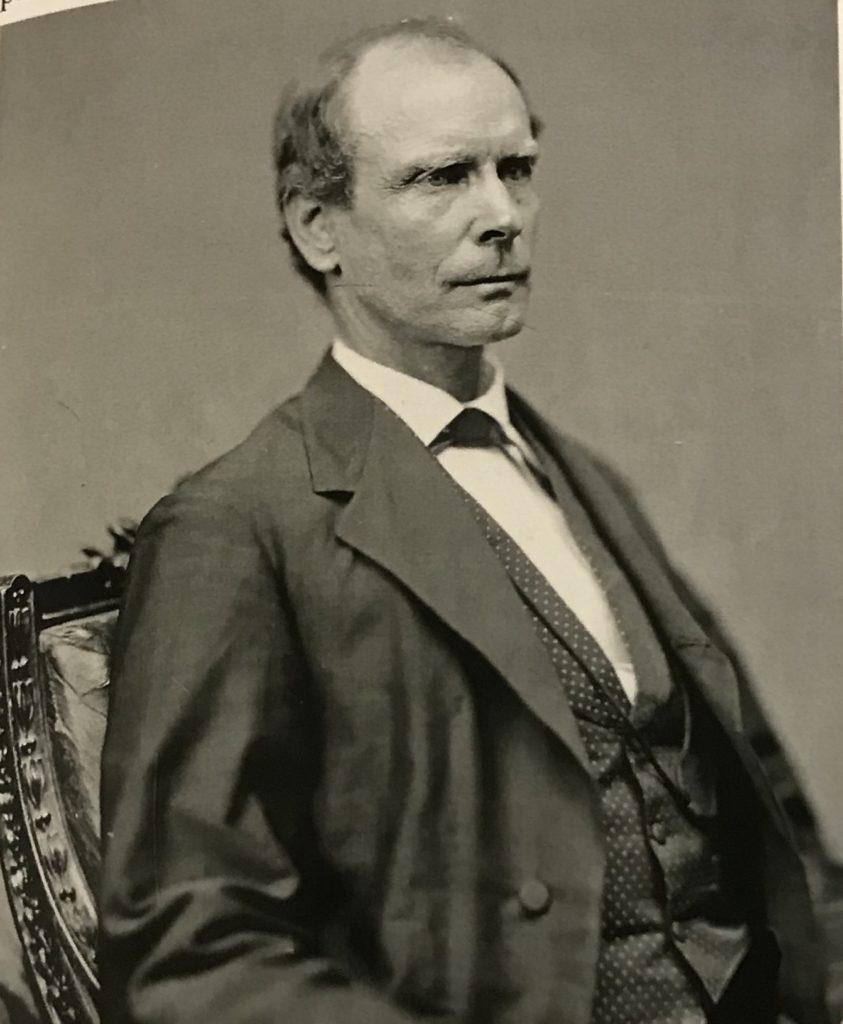

Amos Tappan Akerman, Attorney General of the United States July 8, 1870-January 10, 1872. Photo courtesy of Mark Akerman.

Perhaps these words were left for me, someone of another generation to keep the memory of Amos T. Akerman alive.

Amos was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire on February 23, 1821, the ninth of twelve children born to Benjamin and Olive Meloan Akerman. Benjamin was a civil engineer by trade and of the fifth generation of Akermans to live in North America. According to descendent, Mark Akerman, ”the Akermans of Portsmouth came from the burgher class in England. Their staunch Protestantism was converted into the sterner theology of the Old North Church where the family has occupied a pew for more than two centuries.

Amos began his education in the local school in Portsmouth before transferring to Phillip’s Exeter Academy in 1836. Amos remained at the Academy for three years until August 25, 183 9. With the financial help of his grandmother and a friend at the Academy, Amos entered Dartmouth College, arriving in Hanover on September 27, 1839. That same evening, he was examined by Professors Chase and San borne and admitted as a sophomore. While there, Amos was a member of the United Fraternity, serving as its President from 1841 until May 1842. This was one of two literary and debating societies at Dartmouth. He was also elected to Phi Beta Kappa. During his senior year, Amos was one of four editors of the Dartmouth, a literary magazine in its third volume. After graduating college in 1842 he went to Murfreesboro, North Carolina, where he opened a school and taught for ten months, beginning October 24, 1842. He lived in the home of Dr. Robert Worthington. After a brief trip to Portsmouth, Amos moved to Richmond County, Georgia, at the urging of a former classmate, setting up a new school on January 22, 1844. This new school was financed by Mr. Everett Sapp for the benefit of his own children, but was open to other students. Akerman would teach there until December, 1844. Amos was then employed by John Whitehead of Bath, South Carolina to teach his children and those of his brother. At this point in Amos’ life, he was financially able to reimburse his former classmate at Phillips Exeter Academy who l1ad helped finance his Dartmouth education. Amos would write in his diary that ‘”the fears that I might never pay this debt was a constant source of anxiety until it was fully paid. Then I breathed more freely. I could not bear the thought that he should be the loser through kindness to me.”

In 1845, Judge John Berrien and his family visited the Whitehead home. John McPherson Berrien was a former U.S. Senator from Georgia, a former Judge and a for1ner U.S. Attorney General in President Andrew Jackson’s cabinet. While there, Berrien requested that Akerman become a tutor for his children, which he declined. The proposal was later renewed and accepted, with Amos arriving in Savannah on November 21, 1846. John Berrien was a highly successful lawyer in Savannah and proved a qualified teacher for Amos Akerman, who began his study of the law under hi1n. Berrien had a good law library and Amos read extensively. After about two years, Amos traveled to Peoria, Illinois where his sister Celia Rugg lived. For six months, he worked and studied in the law office of A.0. and A.L. Merriman. The frigid northern climate did not suit Amos, so he returned to the south, settling in Habersham County, Georgia. While working for John Berrien, Amos had spent summers at Clarksville, in Habersham County. In fact, Amos bought the summer home of John Berrien upon his return to Georgia and began farming while continuing to read and study law.

On October 18, 1850, Amos petitioned Judge James Jackson of the Superior Court of tl1e Western Circuit of Georgia for the purpose of being allowed to practice law. Judge Jackson appointed a committee of four to examine Akerman. They found him both knowledgeable and well versed in the law and as a result, Amos was admitted to practice law. Amos remained in Habersham County, both farming and practicing law, until January, 1856 when he moved to Elberton, Elbert County, Georgia. The following July, Amos entered into law practice with Robert Hester and according to Amos, ”In short time the business of the firm became enough to employ all my time, and I have ever since led the life of a busy country lawyer”. In politics, Mr. Akerman was a southern Whig until the party’s demise around 1856. No doubt Amos was influenced by his good friend and former teacher, John Berrien, a staunch Whig. In the Presidential election of 1860, won by Abraham Lincoln, Amos supported the Constitutional Union candidate, John Bell of Tennessee. Bell’s views of conservatism, a vigorous defense of the Union, plus his opposition to expanding slavery into the new territories was very much like that of Amos Akerman.

As the secessionist movement swept across the south, Akerman opposed Georgia’s involvement. When Georgia did finally secede and war broke out, Amos elected not to join the Confederate Army right away. Having been born and raised in the north, his feelings were divided. Amos said, ”I reluctantly adhered to the Confederate cause. I was a Union 1nan until the North see1ned to have abandoned us. In January, 1860, the United States steamer, Star of the West, on her way to relieve Fort Sumter, was fired on by the secessionists of fort Moultrie, and compelled to return to the North. The Militia of Georgia, under orders from Governor Brown, seized Fort Pulaski and the arsenal, near Augusta, and these acts were not resented by the government at Washington. Not caring to stand up fora government which would not stand up for itself, and viewing the Confederate government as practically established in the South, I gave it 1ny allegiance though with great distrust of its peculiar principles”. He did, however, join Company Hof the Third Georgia Cavalry of the State Guard as a private on August 22, 1863. He later served in the quartermaster department, being ordnance officer in the regiment of Colonel Robert Toombs. Captain Amos Akerman later became assistant quartermaster of the militia division under General Gustavas Smith. This placed Amos in the defense of Atlanta in September 1864 and the gradual retreat in the face of Sherman’s famous “march to the sea”.

The Akerman family lot at Oak Hill Cemetery

On May 28, 1864, Amos married Martha Rebecca Galloway of Athens. Amos apparently met her on one of his many business trips to Athens or while serving with the State Guard near Athens.

Martha was the youngest of five children born to the Rev. Samuel Galloway and Rebecca Erwin Scudder at St. Mary’s, Georgia on May 8, 1841. Martha was of distinguished colonial ancestry. Her maternal great-grandfather, James McClain, was killed in battle while serving in the Revolutionary War, his last act having been one of such heroism that congress voted to his family a medal in commemoration of his heroic death. Sadly, Martha was only three months old when her mother died during a yellow fever epidemic at St. Mary’s. The final tragedy of Martha’s young life occurred when her father abandoned his children to their maternal grandparents, Jacob and Hester Scudder, in Princeton, New Jersey. Rev. Galloway then moved to Texas and remarried, dying there in 1891, never having contributed any further support to his children. Martha moved to Athens, Georgia at the age of fourteen to live with her uncle, Alexander Scudder, who ran a boys’ school there. Later Martha attended Mt. Holyoke Seminary before becoming a school teacher in South Carolina. At the request of her Uncle Alexander, she returned to open a girls’ school in Athens. Amos and Martha would eventually have seven children, the three eldest born in Elberton and the others in Cartersville. The oldest, Benjamin, was born in 1866, followed by Walter in 1868, Alexander in 1869, Joseph in 1873, Charles in 1875, Alfred in 1877 and Clement in 1880.

Following the war, the United States Congress had divided the South into military districts in order to speed up reconstruction. Part of this Congressional Plan was to rewrite each southern state’s constitution. The military commander, General John Pope, called for a statewide election in late 1867 in order to decide whether a constitutional convention should be held as mandated by Congress and at the same time elect delegates to the convention. The Georgia voters approved the convention and Amos Akerman was elected one of 166 delegates to it. The delegates were made up of thirty-seven Negroes, nine white carpetbaggers, approximately twelve conservative white Georgians, and the remainder, like Amos Akerman, white Georgians (commonly called scalawags) who wanted to put the ways of the Amos Akerman would become one of the principal leaders of this convention which began on December 9, 1867 in Atlanta and continued until March 1868. It was reported that one of the finest constitutions of any southern state came out of this convention. Amos would be credited with authoring the judicial system embodied in that document. According to From New Hampshire to Georgia, by Mark Akerman, “there was a strong movement in the convention to insert clauses in the constitution which would permit the repudiation of all previous private indebtedness. Since Amos was unable to defeat the movement and did not wish to become a part of it, he resigned and went home. The U.S. Congress would later remove the repudiating clauses when submitted for approval.”

Amos T. Akerman portrait on display in the U.S. Justice Department. Artist, Freeman Thorpe, was paid $5.00 in I875 for his work. Picture courtesy of Mark Akerman.

Akerman had become a member of the Republican party and unlike most Republicans, he enjoyed the esteem of Georgians from all social classes and political beliefs. This was quite a tribute to Amos. For the most part, the Republican party, who held power in this state for a short period following the war, were objects of general indignation and scorn, and their administration of affairs a record of incompetency and corruption. In 1868, Amos became a Grant elector in the former General’s first race for President. The victorious Grant rewarded Akerman for his devotion to his campaign the following year by appointing him United States District Attorney for Georgia. He began his office in December, 1869 and held the position until June, 1870. Amos’ chief concern as District Attorney was violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. He saw too often the rights of the Negro trampled on by many, including State government. The republicans, needing a strong southern voice in Washington, obtained the appointment of Akerman as Attorney General of the United States in 1870. The Attorney General position had just recently become vacant with the resignation of Ebeneezer Rockwood Hoar. Amos was sworn in on July 8th, by Justice Wylie of the District Supreme Court.

The office of Attorney General presented Amos with numerous challenges and responsibilities. For one thing, his duties were expanded by Congress to include supervision of the newly formed Justice Department. All government legal work previously performed by private attorneys was now under the jurisdiction of the Attorney General. Akerman was a firm believer in the law and now as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer, he was sworn to hold everyone in compliance, especially in the south where violence against former slaves was ever increasing. Amos summed up the hatred manifesting itself in the south in a letter to a friend. “A portion of our southern population hate the Northerner from the old grudge, hate the government of the United States because they understand it emphatically to represent northern sentiment, and hate the negro because he has ceased to be a slave and has been promoted to be a citizen and voter, and hate those of the southern whites who are looked upon as in political friendship with the north, with the United States Government and with the negro. These persons commit the violence that disturbs many parts of the south. Undoubtable the judgement of the great body of our people condemns this behavior, but they take no active measures to suppress it.”

Klan violence progressively increased in the south, especially throughout the Carolinas, resulting in new federal laws designed to enforce the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the U. S. Constitution. These Force Acts authorized the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, suppression of disturbance by force and heavy penalties on terrorist organizations. In South Carolina, Governor Robert K. Scott requested and received federal troops. Arrests were made, but it was soon evident that state courts could not and, in some cases, would not protect the rights of negroes. Akerman realized the need to personally go to South Carolina. Amos judged the situation so severe that he requested and obtained an order from President Grant suspending the writ of habeas corpus in nine counties. Suspected Klan terrorists could now be held accountable in the Federal courts without the possibility of being released before trial. Resulting Federal prosecution of suspected Klan members evoked widespread southern sympathy. Southern newspapers such as the Rockhill (S.C.) Lantern lashed out at Akerman and also Major Lewis Merrill, commanding the Federal troops. “If the walls of the McCaw House could disclose the secrets of headquarters, they could a tale unfold that would consign the names of Merrill and Akerman, his legal accomplice in catching Ku-Klux. How the one sunk the office of Attorney General and for two weeks turned constable at York County to prosecute his countrymen.”

Amos Akerman found himself caught in a political inferno between Northerners who were growing tired of the whole Reconstruction issue and Southerners, many in his own party, who refused to accept total equality. However, Amos Akerman did not waiver and continued the fight. Over half the cases prosecuted by Akerman’s lawyers were won.

Of course, the office of Attorney General had its lighter moments, as mentioned in a letter home. “Last night I had a call from one of the sprightliest and pleasantest talkers that I have ever met. And who do you think it was? General Sherman, that terrible ‘vandal’ of whose atrocious march through Georgia you have heard so much. If all vandals are like him, they are agreeable in the parlor, whatever they may be elsewhere!”

The end of his career as Attorney General came when the Pacific railroads became dissatisfied with a ruling he made in regard to a subsidy in public land, in which the Attorney General said their charter did not authorize. According to My Memoirs of Georgia Politics by Mrs. William H. “Rebecca” Felton in 1911, she describes the aftermath of the Pacific railroad decision. “The Secretary of the Interior sided with the railroads, and sought to override the decision. The conflict began. I think the secretary’s name was Delano, one of the men who got into the State Road lease in Georgia, and he understood the temper of our half-frenzied people in Georgia against Republicans – a frenzy that was fanned into a consuming flame by so-called Democratic politicians who were busy all the time in cramming their pockets during Bullock’s reign. This honest man, this upright lawyer, was actually hounded out of General Grant’s Cabinet by men in Washington City, owned and used by these Pacific railroad authorities, and the run-mad politicians in Georgia actually danced in fiendish glee over the result. Genera! Grant stood by his friend for some months, but at last he yielded and asked for Colonel Akerman’ s resignation, but not until an interested person went to Colonel Akerman ‘s wife and hinted that $50,000 would not stand in the way and all opposition to Colonel Akerman would be withdrawn, if the Pacific railroad land subsidy was allowed to stand.” A confidential letter from the President to Mr. Akerman dated December 13, 1871 read,

“Circumstances convince me that a change in the office you now hold is desirable, considering the best interests of the government, and I therefore ask your resignation. In doing so, however, I wish to express my appreciation of the zeal, integrity, and industry you have shown in the performance of all of your duties, and the confidence I feel personally by tendering to you the Florida Judgeship, now vacant, or that of Texas. Should any foreign mission at my disposal without a removal for the purpose of making a vacancy, better suit your tastes, I would gladly testify my appreciation in that way. My personal regard for you is such that I could not bring myself to saying what I say here any other way than through the medium of a letter. Nothing but a consideration for public sentiment could induce me to indite this. With great respect, Your obedient servant,

U.S. Grant.”

Akerman did resign his post on January I 0, 1872 and was succeeded by George H. Williams of Oregon. When asked about his tenure as Attorney General, Akerman would state … “! believe it was satisfactory to the President; but it was not satisfactory to certain powerful interests, and a public opinion unfavorable to me was created in the country. I resigned the office and came home.” To one of his sons he wrote, “Love your country. Be a true patriot. Understand public questions. Ask what is right, try to make it popular; but cleave to it, popular or not.” Amos T. Akerman had never succumbed to the graft and corruption that ruled government and business in the years following the war. He left the office of Attorney General as he entered into it, an honest man dedicated to enforcing the letter of the law and a man whose integrity could not be bought. In his book, Region, Race, and Reconstruction, author William S. Mcfeely wrote, “Perhaps no Attorney General since his tenure … and the list includes Ramsey Clark in the 1960’s … has been more vigorous in the prosecution of cases designed to protect the lives and rights of black Americans.”

The Free Press in Cartersville published this story from the New York Times on February 10, 1881. Among the many stories which are told of the eccentricities of A. T. Akerman, none is more characteristic than that of his encounter with a Western Union telegraph boy. The attorney-general, who had only just been called to his high office, and who knew next to nothing of its duties, was one day very busy at his desk, a pile of papers migher than his head were in front of him, and he had given orders that he was on no account to be disturbed. But this prohibition was not believed to extend to telegraph boys, and one of those industrious and not always well treated Little servants of the public, was admitted. He delivered his dispatch. The attorney-general signed for it without looking up. Then the boy, not noticing that the time was an unfavorable one, began to tell of a project which he and his associates had on hand, and asked for a small subscription. Worn out with work which he did not fully understand, the new attorney general returned such an answer that the boy was only too glad to get out of the office as fast as his active legs would carry him. Then Mr. Akerman went on reading, altering and signing the papers before him. So, he went on for three or four hours, until his work was done. Then he rang for one of his clerks and ordered that the telegraph messenger who had brought him the dispatch be sent for. After some difficulty the boy was found, and, still remembering his former experience, was, trembling and afraid, brought before the attorney general. But the latter, instead of soundly scolding him as he expected, patted his head and said: ”My little 1nan, it is the duty of United States officials to be polite to all those who call on them. This is a rule which I forgot this morning. Here is a five-dollar bill, my subscription to the fund of which you spoke to me; and I beg you, don’t mind what occurred between us a few hours ago.” Attorney General Akerman was not a popular man in Washington, but there were not a few of the official gentlemen who decried him who might with great benefit to themselves and the public have adopted some of his methods.

According to family notes written by Minnie Akerman, the wife of Amos’s third son Alexander, ”Amos never swerved from his loyal devotion to Grant. Nothing could dim his admiration for hi1n nor shake his faith in Grant’s goodness and ability.”

In a letter written to his wife on July 2, 1870, Amos states, ”Last evening I dined at the President’s with four senators. I had the honor of attending Mrs. Grant to the table and of sitting next to her. She is intelligent, ladylike and particularly pleased me by speaking of her husband as Mr. Grant.” Why any man would forgive the ingratitude shown Akerman is far beyond the understanding of most. However, Amos, a man of foresight and judgment, knew and understood the pressures descending upon Grant. A few months before Amos’ resignation, he would write to his wife the following, ”I want you to learn something of the dimensions of a new effort which I am satisfied is going to oust me from office because I will not sub serve certain selfish interests. If nobody but myself is to be affected, I should feel no concern; but I have a delicacy on the point of exposing the President to annoyance and perhaps the censure and dislike of powerful interests, on my part. If the combination is serious in its strength, I have a disposition to get out of the way by resigning.”

Amos never aspired to be a political giant and was just thankful for the opportunity to do his small part in restoring the union.

Akerman left Washington to join his family at their residence in Cartersville, where he had moved from Elberton some twelve months earlier in January 1871, after a storm of controversy while still serving as U. S. Attorney General. In an election held December 20, 1870, Emory P. Edwards, a renowned lawyer of Elbert County, was the Democratic candidate for representative. He was opposed by Nathaniel Blackwell, a former slave. When the votes were counted, Mr. Edwards had won by a vote of almost four to one.

Amos Akerman was very interested in the candidacy of Blackwell back in his home county. According to the History of Elbert County, Georgia, 1790-1935, Amos made a special trip fro1n Washington, D. C. to cast his vote for him. Akerman apparently had an interest in seeing that the rights of Blackwell were protected, as well as those of Negroes who had not so long before been granted the Right to vote. While home in Elberton, he assembled a crowd of Negroes, encouraging them to exercise their right to vote and attempted to lead the1n to the poles. His actions proved very unpopular to a community inhabited by white people slow-to change fro1n their old southern ways and beliefs. The History of Elbert County, Georgia 1790-1935 went on to say that as a whole, Negroes remained with their old masters after Emancipation and disregarded the efforts of those like Mr. Akerman who attempted to arouse their right of freedom. No doubt, intimidation, fear, a lack of skills, wealth and education had a lot. to do with the failed efforts of Amos Akerman. His actions during the election would leave the Akerman family as outcasts in a community they considered home. The Elberton Gazette on January 3, 1871 carried this notice: ”Departed: Attorney General Akerman left this place (perhaps forever), on Wednesday last, apparently disappointed and disgusted with the result of the elections. We care not how long he 1nay live, nor how far he may go. He carried his family with him.”

Akerman pursued his work as an attorney in Cartersville. He was said to have had a large and lucrative practice in the United States Courts, where he was regarded as the equal of any in_ legal ability. Amos chose Cartersville for several reasons, one being its location on the railroad. Another reason was his family’s strong ties to the Presbyterian faith and Cartersville had a flourishing parish. The political and racial climate in Cartersville was much more subdued and provided a safe environment for the Akermans. We also know that Amos was a good friend of Warren Akin, a local Bartow County attorney noted for serving as the Speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives in 1861, for serving in the Second Confederate Congress at Richmond and for pleading the first four cases of the Georgia Supreme Court. Warren had strong family ties to Amos’s former home of Elbert County, being born there in 181 1. Akin apparently had great respect for Amos’ legal ability, calling upon him in May, 1865 to intercede with U.S. occupational forces in order that he could return home without fear of being arrested for his role in the Confederate Government. The large two story Akerman home was located at what is today 336 South Tennessee Street. It was built in 1848 by a Mr. Woodbridge. The house previously had two other owners. The first was Malcomb Johnson and the latter a Col. Pritchett who sold it to Akerman. Unfortunately, the home was destroyed by fire in 1900 while the residence of Amos’ third son, Walter.

Site in Cartersville of Amos Akerman ‘s home. The actual house on South Tennessee Street was totally destroyed by fire on September 26, 1900.

Amos loved Cartersville and remarked more than once that he would spend the remainder of his life here. He was very active in the affairs of the Presbyterian Church and continued his hand in national politics supporting the Republican Party. In fact, in the months prior to his death, he took several extended trips in support of the Republican party, coming home greatly fatigued. During the elections of 1880, he spoke in several of the northern states to great crowds, often making addresses two hours and upwards in length. In southern Ohio, Amos and Eugene Hale, of Maine, were announced to speak. Mr. Akerman was on time and talked for two hours. A dispatch was sent him to hold the crowd until Hale could get there. Fresh trainloads of eager Republicans had just come in, and rather than disappoint them, he rallied his remaining strength and continued to speak until he broke down from sheer exhaustion.

Amos T. Akerman died on Tuesday night, December21, 1880, after being stricken with rheumatic fever the Thursday before. He had been attended by his longtime friend, Dr. H. W. M. Miller of Atlanta. The announcement the following morning of his death brought great sorrow to our community, the state and the nation. Georgia had lost one of her best citizens, and the Republican Party the man to whom more that any other they have looked to for counsel and guidance.

The funeral took place the following Thursday afternoon with the Rev. Theodore E. Smith of the Presbyterian Church officiating.

The Cartersville Bar, City government and a large number of citizens packed the church to hear a most earnest and tender tribute to Amos Akerman. The local press reported that none had any but the kindest utterances of regard and esteem for Mr. Akerman. Those who had most widely differed with him in politics were readiest and foremost in making acknowledgments of his high character, his great attainments and his unselfish pure life.

Prior to Amos’ death, a movement was underway to obtain for Amos an appointment to the U.S. Federal Circuit Court of Appeals. ”Resolved by the members of the bar and citizens of Bartow County, Georgia that we recognize the eminent ability, the unswerving integrity, and commanding influence of the Hon. Amos T. Akerman, avail ourselves of this opportunity to endorse his candidacy for the appointment of judge of the United States Court of the fifth judicial circuit and to express our earnest desire that the same may be conferred upon him. Although every member of this meeting is a democrat and differing entirely fro1n Mr. Akerman politically, yet such is our confidence in hi1n as a citizen and a lawyer, that we feel his appointment would prove eminently satisfactory to the people of the state wherein he will be called to preside, and will do much to conciliate them and strengthen their faith in the administration appointing him.” Weeks after his death, the ”Washington Star” reported: ”It is stated that the President had fully made up his mind to appoint the late Attorney General Akerman to the vacant circuit Judgeship occasioned by the promotion of Judge Woods to the United States Supreme Bench.”

The death of Mr. Akerman at the age of 59 had left his widow alone with seven children ranging from a few months to fourteen years. Life is not always fair, but with God’s help all seven children grew up to live productive lives. Benjamin, the eldest, was a mining engineer in Mexico. His life ended in Washington State on December 17, 1927. He is buried in the family plot at Cartersville’s Oak Hill Cemetery. Walter was Postmaster in Cartersville for 22 · years, a teacher, a WWI veteran and a U.S. Marshall. His last job was as a Public Relations Special Agent for the Seaboard Airline Railway. Walter passed away April 29, 1951 and is also buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, along with his wife Susan Young Akerman. Alexander became a lawyer serving as U. S. District Attorney for the Southern District of Georgia. He would later practice law in Orlando, Florida before being appointed as Federal Judge tor the Southern District of Florida. Alexander died August 21, 1948. Joseph would become an obstetrician and educator, serving in the latter capacity at the University of Georgia as a professor of obstetrics until his death on December 9, 1943. Charles also would become a lawyer, setting up practice in Macon, Georgia. He died November, 1937 in Macon. Alfred was State Forester for Massachusetts, professor of Forestry at the University of Georgia and last, chairman of the Forestry Department at the University of Virginia. Clement was a Lieutenant on Pershing’s staff during WWI and assisted the War Department in compiling a history of that war. He would afterwards serve as a professor of economics at Reed College in Portland, Oregon.

Mrs. Akerman remained in Cartersville until 1892 when she moved to Athens. She became greatly interested in missionary work for the Presbyterian Church and traveled extensively too many foreign lands. Martha Akerman died at her home in Athens on Friday, January 19, 1912 from heart failure. Her remains were returned to Cartersville for burial beside her husband.

The late Rebecca Felton wrote this story in My Memoirs of Georgia Politics, which attests to the honesty and integrity of Amos Akerman. ”The Honorable Mr. Stephens (presumed to be Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy, a U.S. Congressman, a Georgia Governor and a close friend of the Feltons) said to me: When Honorable Thomas W. Thomas of Georgia, lay on his deathbed he told his wife that he wished to advise her as to the future .. Said the dying man: If you need a lawyer, and you will need one, I tell you to employ Colonel Akerman. I know him-he is absolutely honest. He will serve you well and he will treat you right.”

So, remember this man of national prominence who was the only ex-Confederate to serve in a Presidential Cabinet during Reconstruction. Amos Tappan Aker1nan, like so many others, migrated to Bartow County only to call it home.

This article was compiled by Guy Parmenter with the assistance of J. Mark Akerman (Lake City, Florida), Francis Akerman (Opa Locka, Florida), Robert W. Wilson (Orlando, Florida) and the Bartow History Center.