Alexis Carter-Callahan, M.A.

George Washington Carver State Park

“this is about more than color. it is about how we learn to see ourselves. it is about geography and memory.” –the river between us in Mercy by Lucille Clifton (2004)

Introduction

The creation of the historic George Washington Carver Park is Georgia’s stake in a nuanced and complex understanding of the African American relationship with recreation and the environment. Jim Crow era politics would leave African Americans largely excluded from access to state parks. John Loyd Atkinson Sr.’s vision for the future of black recreation in the South, however, contributed largely to the Civil Rights Movement, particularly the environmental movement. His role as the visionary and environmental architect of the park contributed to a larger conversation surrounding access to the natural environment for marginalized cultural groups. Through his efforts, black families from Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama and other areas in the Mobile Basin were allowed to freely indulge in the spoils of the natural environment without restriction in an era of “separate but equal.”

Park Establishment

The early twentieth century brought flooding to areas throughout the United States, requiring Congress to address issues of safety and protection. In 1928, Congress responded with the Flood Control Acts. These regulations would allow the U.S. Corp of Engineers and the Federal Power Commission to conduct a series of annual feasibility studies on areas prone to flooding. These studies would aid in future construction to alleviate potential flood problems. Areas that received assistance from this program were able to experience relief from flooding through flood prevention mechanisms, as well as in ways such as access to water, jobs, and recreation. President Roosevelt’s New Deal funding would eventually reach Acworth, Georgia with the Allatoona Reservoir on the Etowah River in the Coosa River Basin project, also known as the Allatoona Dam. Three million dollars was allotted by Congress in 1941 to the “initiation and partial accomplishment of the project.” World War II would create a decrease and redirection of funding from construction projects, including the Allatoona project, to war relief and defense. However, post WWII legislation would again see a rise in funding for flood relief. On June 15, 1946, Governor Ellis Arnall, Georgia 7th District Congressman Malcolm C. Tarver, and Lt. General Raymond A. Wheeler, Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, hosted a ground-breaking ceremony resulting in the launching of the four year project of building the Allatoona Dam. The Dam and surrounding acreage would span 1457 acres and see completion in 1950.

Congressional Flood Control Act, 1941

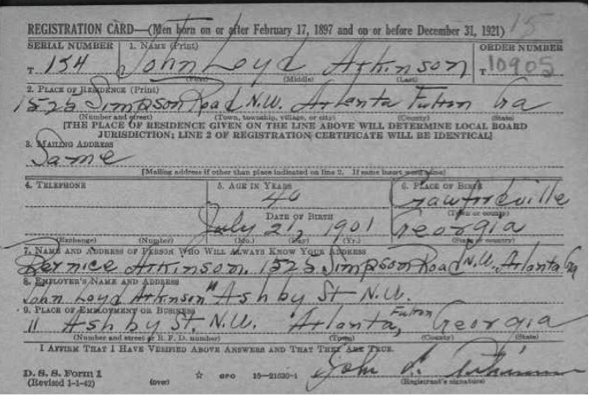

John Loyd Atkinson Sr.

In 1941, John Loyd Atkinson Sr. purchased land to build a home in the J.A. Coursey subdivision in Fulton County. In early September, as he began to bring in lumber to begin construction, a neighbor approached with a question:

“I talked to Atkinson at that time. . . I happened to see some lumber on this lot, a small pile of lumber, and about three people down there at work. . . I . . asked him what he was doing. He said he was fixing to build a house, and I says, `The heck you are,’ and he says, `Yes,’ and I turned around and walked off, and he says, `Well, what is wrong about it?’ And I said there was plenty. . .”

This encounter would be one of many that Atkinson would face as he worked to become a homeowner in the J.A. Coursey subdivision, but also as he later navigated the southern landscape of marginality politics. Atkinson would eventually become an involved party to the Georgia Supreme Court Case, Atkinson v. England (1942). This case would debate the legitimacy of land being sold to a black man in a “Caucasian only” subdivision. During the time of the case, Atkinson was stalled for two years from developing a house on the property in the subdivision. The two years of waiting for a decision, which later would be ruled unanimously in his favor, led to Atkinson joining the United States Air Force, serving as a Tuskegee Airman. Atkinson was not a stranger to the policies and politics of segregation.

John L. Atkinson, Sr. Georgia WWII Draft Registration Card, 1940-1945, Credit: Family Search

Upon returning home in 1943, Atkinson was inspired to build a private, black resort modeled after Florida’s first black millionaire, Abraham Lincoln Lewis’ American Beach. Also known as the “Negro Ocean Playground” and located just north of Amelia Island, Florida, American Beach was created for black families to compensate for the effects of Jim Crow laws. The 216 acre recreational beach was on the musical chitlin’ circuit for many famous artists of the 1940-1950s, including Duke Ellington. Its motto was simple: “A place for recreation and relaxation without humiliation.”

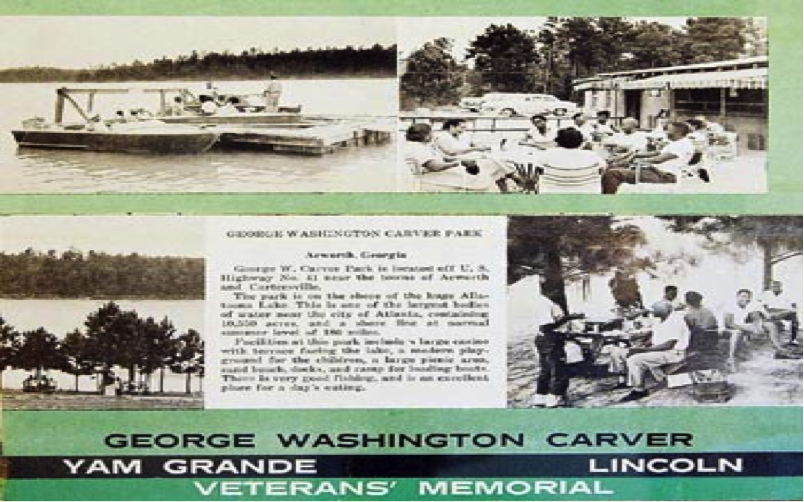

Atkinson attempted to create a similar, private resort in Northwest Georgia for 5 years without substantial progress. As African American demands for access to public parks increased nationally, state politicians were increasingly subject to pressure to create black outdoor recreation facilities. Under the New Deal Administration, the National Parks Service worked to alleviate this pressure by creating Negro Parks through the Recreational Demonstration Area program. Few of these parks were built before the start of WWII, but, post-war efforts at providing “separate but equal” facilities opened a door for Atkinson to advocate for the lease of 345 acres of land through the U.S. Army Corps. Governor Eugene Talmadge assisted with securing the permit from Bartow County to create the beach. John Loyd Atkinson Sr. would be appointed the first black superintendent of the only black Georgia state park to be named after an influential African American, the George Washington Carver State Park.

Park Operation

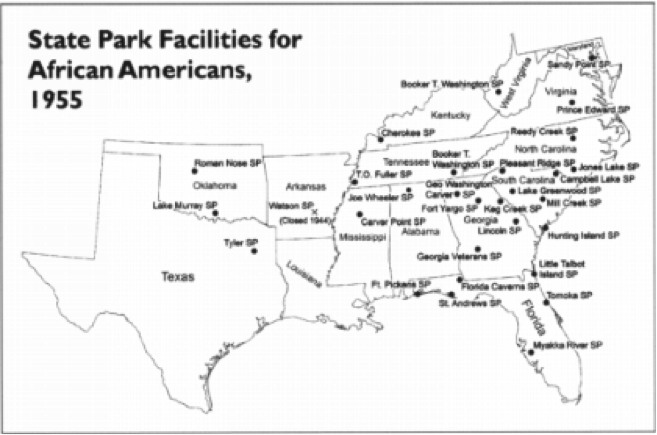

State parks with facilities accessible to African Americans in 1955. Credit: State Parks and Jim Crow in the Decade before Brown v. Board of Education, William O’Brien, 2012

John Loyd Atkinson, Sr. served as the first superintendent of George Washington Carver State Park, serving from 1950-1958. Atkinson relied heavily on his family to assist with the physical creation of the beach. Sand was carried to the area in his family pickup truck. The family spent time pouring into the sand covered shorelines of the beach. In addition, Atkinson oversaw the building of a concession stand, boat ramps, playground, beach house, clubhouse, and the home where the Atkinsons resided during the summer season while the park was open.

Atkinson also encouraged participation in skill attainment and leadership through outdoor activities. Boy and girl scout troups were regularly welcomed to the property. A segregated Girl Scout camp was established that allowed scouts access to hiking, camping, and archery. In 1963, Atlanta’s first African American Girl Scout troup, District V, produced a brochure called Camping for Me that documented George Washington Carver Park as the location of its first official campsite.

The honorable Justice Robert Benham spent his adolescent years, ages 11-15, adding to the historical memory of the park. Benham’s father, Clarence Benham, served as the second superintendent from the years 1959-1962. Justice Benham and brothers grew up swimming at the beach, and also serving as lifeguards. Herbert Kitchens would follow as superintendent, with Samuel Nathan serving as the last superintendent of the park.

The beach was a stop on the Southern chitlin’ circuit, hosting musical greats such as Ray Charles and Little Richard. Local rumors suggest that a young Otis Redding, who played in Little Richard’s background band called the Upsetters, also visited the beach on the circuit. Many of the black elite families of Georgia, particularly from Atlanta, often frequented the beach. Civil Rights Leaders, Andrew Young, and the late Mrs. Coretta Scott King acknowledged that their families spent time enjoying the access to the beach. Serving as one of the South’s “black meccas,” George Washington Carver Park was not just a getaway for the black elite, but it also served as a recreational safe haven for the entire black community. Timothy Houston, Sr. described his personal experience with the beach in the History of the Cobb County Branch of the NAACP and Civil Rights Activities in Cobb County, Georgia interview (2009):

“We had our own beach called George Washington Carver, it was at Red Top and it was nice. It was a real nice facility and I remember we used to sit around the porch at my moms’. We lived right up from Cherokee Street and that was the only way through, I-75 wasn’t here then and that was the only way people come from Atlanta and Marietta, to get to Red Top Mountain. We would sit there on Sundays and you could count the vehicles, it would be ten or fifteen chartered buses. That is when we seen actual black people in real nice cars. They would come in their nice cars like a convoy going to the beach, going to George Washington Carver. That was every Sunday; people coming from all over. That was the only black beach in the area. You go out there and they had a huge hall, they had a kitchen and a big dance floor and then you had the beach where you would swim. It was really nice.”

The NAACP worked to push post-Brown legislation for equal access to state parks, with successes in cases in Virginia (Prince Edwards Recreation Park, 1947) and Maryland (Lonesome v. Maxwell, 1954). The 1960’s introduction of integration contributed greatly to less attendance at segregated facilities, as black patrons were no longer required to travel considerable distances for access to the natural environment. In 1975, due to budget cuts with the state of Georgia, George Washington Carver Park was released from state management to management by the Bartow County Government. The park’s name was changed to Bartow Carver Park. The Cartersville-Bartow County Convention & Visitors Bureau would begin overseeing management of the park in 2017, restoring the park to its original name. Currently, the park is open for daily use and reserved for private events. Memories Day, an annual community celebration, is held to commemorate the park’s place in the larger context of the fight for equality, as well as to honor the memories of those that enjoyed the vision set by Atkinson over seven decades prior.

References

Amold, Joseph L. The Evolution of the 1936 Flood Control Act. Office of History United States Army Corps of Engineers, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, 1988. Accessed: https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerPamphlets/EP_870-1-29.pdf

Bartow Carver Park takes center stage at BHM, Daily Tribune News, February 2017.

Burkett, Edmund B. Allatoona Dam and Lake: A Perspective on Story and Water Supply Usage, 1993.

District V Exhibit: First African American Girl Scouts in Atlanta. Acccessed:

Ffrench, Jennifer. Crossroads News: George Washington Carver Park, March 2018

George Washington Carver Park, Accessed: http://visitcartersvillega.org/gwcp/

History Of Allatoona Lake Accessed: http://www.lakeallatoonaassoc.com/history_of_lake_allatoona

History of the Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites Division. Accessed: https://gastateparks.org/sites/default/files/parks/pdf/HistoryOfGSPHSD.pdf

History of American Beach. Accessed: https://www.americanbeachmuseum.org/about-us/

Manganiello, Christopher J. Southern Water, Southern Power: How the Politics of Cheap Energy and Water, 2015.

Many Rivers to Cross: Charles Atkinson. Accessed: Many Rivers to Cross, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/your-stories/charles-atkinson/

O’Brien, William E. State Parks and Jim Crow in the Decade Before Brown v. Board of Education, Geographical Review, Vol. 102, No. 2 (April 2012), pp. 166-179.

Supreme Court of Georgia, England v. Atkinson, 26 S.E.2d 431 (Ga. 1943). Accessed:

United States Army Corps of Engineers, Report of the Chief of Engineers U.S. Army, Part 1, Volume 1, p. 909.

Zibanajadrad, Claudia and Walker, William. KSU Oral History Project: History of the Cobb County Branch of the NAACP and Civil Rights Activities in Cobb County, GA. Interview with Timothy Houston, Sr., October 2009, p.11.