Understanding Early 20th Century Tenant Farming in Bartow County, Georgia

Practicum in Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Dr. Terry Powis

The Adams family house is a historic building situated in Cartersville, Bartow County, Georgia located only a few miles northwest of the Etowah Indian Mounds. The house was constructed on the Walnut Grove Plantation, owned by the Young family since the early 1830s. Abandoned for nearly six decades, my research focuses on rediscovering what we know about the daily life of the Adams family through archaeological investigation, archival study, and oral history. Uncovering the lifestyle and mode of production of this specific tenant farming family adds to the understanding of tenant farming in general. I was interested in studying this family and historic site in particular to document the information before it was lost forever.

Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which farmers cultivate crops or raise livestock on rented land. In order to work the rented land, tenant farmers generally provided their own tools and plow animals and were allowed to retain half of the harvested crops. Landowners provided shelter, food, and other necessities that were to be repaid from the tenants share of the crop. So, although they were allowed to keep half of the crops they sowed and reaped, the money earned from their personal bounty ultimately went back to the landowner (Boundless 2018). Tenant farming became prominent directly following the American Civil War due to the bad economy former slaves and poor whites faced. Following Reconstruction, tenancy became the way of life in the Cotton Belt (Conrad 2007).

Background

The Walnut Grove Plantation is located in Cartersville, Georgia, neighboring the Etowah River and Pettit Creek. For this, its original landowners Dr. Robert Maxwell Young and his wife Elizabeth Caroline Jones Young regarded the property as “the beautiful rolling land in the horseshoe bend of the Etowah River” (Cummings 2009, 5). Native to Spartanburg, South Carolina, the Young’s began their search for property in 1832, specifically looking to speculate in Native American land (Billingsley 2020). They searched for land throughout Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana before finally applying for a land grant in Georgia for Walnut Grove.

It was only due to the forced relocation of Native American people in 1832 that the Young family was able to obtain this property. Prior to this, Cherokee government heavily resisted the push for white settlers inhabiting their land. However, once Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1828, he immediately declared the removal of eastern tribes to be a national focus (Davis 1973, 312-17). Several factors accelerated the push for Cherokee removal, most notably the demand for arable land during the rampant increase of cotton agriculture. Cherokee land plots were then divided out to white Georgians in what is known as the Georgia land lottery (Garrison 2004).

Bartow County, formerly known as Cass County, was thriving at this point, producing iron, tobacco, corn, wheat, and of course cotton. It wasn’t until the end of the Civil War in 1865 that the American South in its entirety was left in devastation. Over four million slaves were emancipated as a result of the Civil War, much to the dissatisfaction of slaveholders in Bartow County (Hebert 2017). Economic reconstruction had to happen quickly, as the problems the south faced were more severe than just damaged equipment and neglected fields. This social revolution reorganized the labor force, creating a free-labor social system in which neither blacks nor whites were familiar with. As the south still heavily relied on agricultural production, the transformation from a slave society to a society based on free labor began (Woodman 1975, 319-20).

Methodology

| Figure 1. Before and after site clean-up. The top photo shows the overgrown Adam’s family house. The bottom photo is after I removed foliage. |

Data collection for this study included a combination of field and lab work along with oral history and archival research. The first step on site was to clean up overgrown foliage that prevented a clear view of the surviving architecture. Utilizing loppers and a hand saw, I devoted four weeks to the removal of trees, branches, vines, and other dense shrubbery that veiled the site (Figure 1). Once the structure was clearly visible from all cardinal directions, I was accompanied

by Dr. Terry Powis and Kong Cheong in creating a site grid in order to map the house. The five-meter grid was coordinated using a transit level to position stakes exactly five meters apart extending north-south and east-west. Due to the precision of the transit level, we knew that the grid was positioned to true north with exact 90-degree angels in relation to the other directions. A 50-meter open reel tape measure was then spread along the grid lines to begin mapping. Arbitrary

points were selected on the house every one to two meters, where the distance from the

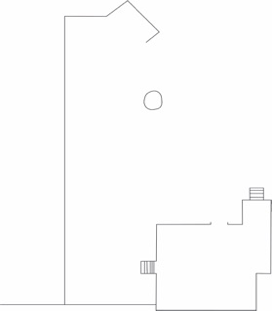

grid line to the structure was measured. Figure 2 shows a digital rendition of the completed map.

While this method created a two-dimensional map of the houses orientation, it doesn’t provide any information on the height range of the structure. In order to map height differences throughout the structure, I created a profile running a leveled line running north-south directly through the center of the house. Similar to the previous mapping method, A 50-meter open reel tape was positioned on the line and points on the house were measured vertically from the fixed line. After spanning the entirety of the house, I then fixed a line running east-west through the house and measured vertically once again. This approach allowed for the mapping of actual features of the house like the front stairs, porch, floor, chimney, and root cellar. I then composed a third map measuring the distance of the house to other major elements surrounding the site including the cotton field and a well. Creating a map with the surrounding features provides more context to the house in relation to the landscape.

Due to the house’s close proximity to a prehistoric Native American village (dating from AD 1200-1300) known as the Cummings Site, all of the artifacts collected through dirt screening were combined with prehistoric artifacts including pottery sherds and chert flakes. Therefore, the first phase in the lab was to discern historic artifacts from prehistoric. There were around 50 two-gallon zip lock bags containing artifacts that needed to be sorted. First, I poured out the contents of the bag onto a tray and carefully examined every piece to determine its placement whether historic, prehistoric, or rock. Once the entire bag was sorted, I put the historic artifacts in their own bag with the parent bags provenience information as well as the prehistoric artifacts in their own bag with the provenience information. After completely sorting through all parent bags, I was left solely with historic artifacts.

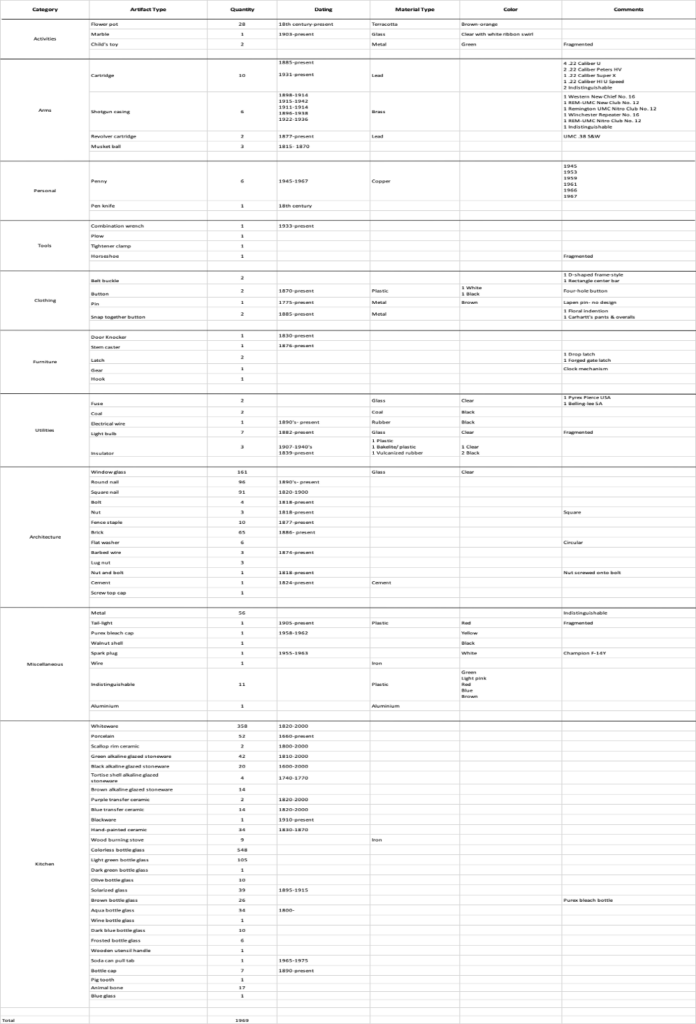

In order to accurately view and date the artifacts, they first needed to be washed. Using a tub of water and a toothbrush, I scrubbed every individual artifact clean and left them out to dry, always making sure to keep them with their corresponding bag. Once all the artifacts were cleaned, I began sorting them into like groups using Stanley South’s 1978 Artifacts Classification System. Stanley South is regarded as the “Father of American Historical Archaeology” as he pioneered the process of pattern recognition to group artifacts from historical sites (South 1978, 223). The classification system is based on the original intended function of the artifact. South deliberately fashioned this model to historic sites in order to allow intersite comparisons using group regularities. The concept of combining artifacts into functional groups for investigation remains a fundamental in historical archaeology (Sewell 2004, 23). While the lab work is based off of South’s classification scheme, I modified the groups in order to properly fit my assemblage of artifacts. I organized all the artifacts into the following groups: Kitchen, Architecture, Furniture, Clothing, Tools, Arms, Personal, Activities, Utilities, and Miscellaneous. Ensuring that each artifact retained connection with its appropriate provenience data, I put the separated artifacts in their own bags and placed them into their designated group. Once all the artifacts from every bag had been organized and placed into their categories, I began to date them utilizing online resources and reference books. I then compiled an excel spreadsheet detailing the category, artifact, quantity, date range, material type, and color (Appendix 1).

Although analyzing the archaeology of the house was the primary focus, oral history and archival research were pivotal in supplementing what the archaeological data communicated. Due to the fact that only three people still alive today have any association to this house and its inhabitants, the information was limited yet revealing. I conducted three informal in-person interviews with an informant that resides about 50 meters east of the Adams family house on the Walnut Grove Plantation. Some questions of interest were:

- What year was the house constructed?

- What were they farming? Did they farm the same crop year-round?

- What was their mode of transportation?

- Did they have electricity?

- What year was the home abandoned and for what reason?

The other two informants were contacted via email to fill in any potential gaps or add additional information. Archival information was also narrow, however Georgia’s Natural, Archaeological, and Historic Resources GIS web-based registry (GNAHRGIS) was utilized to find any cataloged information on this historic site.

Results

| Figure 3. Elements of the Adam’s Family House. Photo (a) shows the firebox portion of the brick chimney. Photo (b) is the root cellar. Photo (c) is a supporting brick wall in the root cellar. Photo (d) shows the central stairs leading to the front porch. |

Results from the field work illustrate that this is a 1,020 square foot home with a cinderblock foundation, cement porch with central stairs, brick chimney, and a root cellar (Figure 3). The house also features a back porch with cinderblock stairs on the north west side. There is evidence of a gravel drive extending from the southwest side of the house northward. The house is situated about 17 meters north of a cotton field. There is also a well located around 30 meters

west of the structure. Similarly, there is a parking area about 75 meters from the structure to the west.

A total of 1,969 artifacts were collected and dated, generating a time frame spanning from the 18th century to the present. The artifacts were categorized into ten groups: Kitchen, Architecture, Furniture, Clothing, Tools, Arms, Personal, Activities, Utilities, and Miscellaneous. In the Kitchen Group, a total of 1,360 artifacts were collected, in which 780 were bottle glass, 411 were ceramics, and seven were bottle caps. In the Architecture Group, a total of 445 artifacts were collected, in which 91 were square nails, 161 were window glass, and three were barbed wire. In the Furniture Group, a total of six artifacts were collected, in which one was a door knocker and two were latches. In the Clothing Group, a total of seven artifacts were collected, in which two were belt buckles and two were buttons. In the Tools Group, a total of four artifacts were collected, in which one was a combination wrench and one was a horseshoe. In the Arms Group, a total of 21 artifacts were collected, in which six were shotgun casings and 10 were cartridges. In the Personal Group, a total of seven artifacts were collected, in which six were pennies and one was a pen knife. In the Activities Group, a total of 31 artifacts were collected, in which 28 were flowerpot pieces and two composed a child’s toy. In the Utilities Group, a total of 15 artifacts were collected, in which two were coal, three were insulators, and seven were light bulbs. In the Miscellaneous Group, a total of 73 artifacts were collected, in which one was a spark plug and one was a Purex bleach bottle cap.

The information gathered from oral history further clarifies that this house was in fact inhabited by a tenant farming family. The local resident I spoke to grew up on the property and has resided there for decades. “Informant O,” as he wishes to remain nameless, explained that this house was occupied by a tenant farmer by the name of Charles Adams and his mother, Eleanor Adams. He recalls that Eleanor was a nurse by trade and would oftentimes visit people when they were sick. When asked about children being present in the home, Informant O claimed that there were never any children, although artifactual evidence conflicts with this statement. According to Informant O, Charles Adams was responsible for farming several sections of cotton fields, in which each field was composed of 20 acres. He stated that they farmed cotton exclusively and removed burrs in the off season. He recalls them operating John Deere tractors but didn’t know where they were stored when not in use. He was unsure what year the house was built and also unaware of the year or reason of its abandonment.

Informant O describes the dwelling as originally having wood paneling and plank floors, but sometime after its construction updating to sheetrock walls. He explains that there was a garden adjacent to the home on the east side as well as a space for the chickens they kept for eggs. When questioned about a vehicle, Informant O recalls that they had either a 1950 or 1951 Ford truck. While he was aware of the existence of a barn, he did not know what was kept inside or what it was used for. Finally, when asked about their bathroom situation he didn’t recall there being an outhouse, but really wasn’t aware on how they handled their waste as it “wasn’t any of his business.”

Landowner Ann Cummings, as well as Andy Dabbs who grew up on a piece of land bordering the Cummings Site, were contacted via email for any additional information they could add. Dabbs explained that to his best memory the house was empty around 1964-65. He remembered a farmer by the name of Buddy Tatum who farmed the Cummings and Dabbs farms. According to Dabbs, Tatum and a crew put a new tin roof on the house in the mid 1960’s while the house was vacant. He went on to say that no one ended up inhabiting the house and a tree limb fell on the roof letting water in and accelerating its deterioration. In terms of Ann’s memories of the house and its occupants, she recalls when she first married her husband Skip in 1957, she would come to the Walnut Grove Plantation house to visit and Skip’s mother would be visiting with Eleanor in their kitchen.

According to Georgia’s Natural, Archaeological, and Historic Resources GIS web-based registry, the Adams family house was constructed in 1910. It was a single-story, L-shaped gabled wing cottage with two rooms. The archival document provides a black and white photo of the house from some meters away, but it is virtually impossible to make any details out due to lack of clarity. This type of home structure is consistent with the house Informant O still resides in today that was built in 1920.

Discussion

The field and lab work combined suggest that the Adams’ were a typical tenant farming family that lived to work and worked to live. However, they may have been a little wealthier than average, due to Eleanor Adams working as a nurse and supplementing their income. Similarly, physical evidence and oral history solidifying that they had a vehicle could further indicate excess money. Tenant farmers generally didn’t produce extra capital as the harvest they retained was minimal following deductions from landowners for living expenses. This begs the question, was it actually out of the ordinary for tenant farmers to have a vehicle? Could a vehicle possibly have been considered a living expense that was purchased by landowners and then repaid by tenants? Through oral history I discovered that the Adams’ had either a 1950 or 1951 Ford truck. That is to say that the soonest they possibly could have had a vehicle was 1950. It is known from archival resources that this house was constructed in 1910. Therefore, Charles Adams and his mother Eleanor lived here for 40 years without a vehicle. So, it would be plausible to say that any left-over income they had after paying living expenses could accumulate over 40 years to be able to afford a vehicle themselves. It could also be discussed, however, that a vehicle was simply provided to them by the Cummings family.

Artifactual evidence and oral history suggest the Adams family house had electricity, although there are still questions surrounding its introduction to the house. The house was designed and built with a root cellar, known to be utilized for cold storage. Although if the house had electricity at the date of construction, a root cellar for cold storage wouldn’t have been necessary. The typical Georgia farm family had no electricity, no running water, and no indoor bathrooms (Zainaldin 2007). However, legislature introduced by Roosevelts New Deal brought electricity to rural residents by 1936. Rural electrification was crucial in Georgia where in 1930 almost 70 percent of the population lived in rural areas (Dobbs 2016). While electricity wasn’t readily available to rural areas at the date of construction, the Adams family house could have had electricity as early as 1936.

While the artifacts collected from this site supply a time frame spanning from the 18th century to the present, the majority of artifacts date between 1830 to 1940. So why would there be so many artifacts that drastically pre-date the 1910 construction? One reasoning could be that since these tenants were extremely poor and only given what the landowner at the time provided, their house was furnished with dated leftovers the landowner had readily available. Another theory is that this is the location of a log cabin the Young family lived in from 1835-1837 while their house was being built. It is a fact that the Young family lived in a log cabin while their house was being built, however its exact location is still a mystery. The close proximity of the Adams house to Walnut Grove Plantation could have proven beneficial to Dr. Robert Maxwell Young as it is said he required all the building materials were to be made from resources found on the property (Billingsley 2020). Young could have easily supervised his hired help by residing only a mere 200 meters from the construction site.

Additional evidence to support the notion that the Young family’s log cabin was positioned in the same spot as the Adams family house is the presence of square nails collected from the site. Square nails were produced by hand and utilized from 1820 until 1890. It wasn’t until the introduction of machine-made round nails in 1890 that square nails became antiquated. At that point, houses started to be built using round nails rather than square nails. However, 91 square nails and 96 round nails were recovered on site. By 1910, the year of this house’s construction, it can be anticipated that round nails would have been used exclusively. Although that isn’t the case, whereas there is almost as many square nails as there are round. This could be due to left over materials the Young family had on hand after the construction of their house was built, or it could imply the location of their log cabin.

Several other artifacts equally support the idea of a preexisting structure in the same location. Heavy duty nuts and bolts were recovered that could have been required materials to hold together and support logs. Likewise, most of the dinnerware ceramic dates to around 1820-1830, which lines up with when the Young family would have been residing in a log cabin. It is a fact that tenant’s houses were furnished by landowners, so it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that when the Young family provided the farmers this house in 1910, they simply supplied it with their outdated dinnerware. It’s probable that after years of the same dishes they would have been ready for an updated set anyways.

The presence of a well 30 meters from the house further insinuates they did not have indoor plumbing and rather got their water from the well. Likewise, the parking area not too far

from the well provides more evidence to the addition of a vehicle (Figure 4).

| Parking area and well in relation to Adams family house. Illustration courtesy of George Micheletti | |

The barn is another associated feature of this site that not a lot of information could be collected on. When asked about the barn, Informant O told me that he did not know what was kept in the barn. However, he did inform me that somebody by the name of Charlie Dabbs hanged himself in the barn. This is interesting because Andy Dabbs, the other local that was interviewed, revealed that Buddy Tatum, as previously mentioned, committed suicide years after putting the new roof on the house. I searched several Cartersville and Bartow County obituaries for a “Charlie Dabbs” or “Buddy Tatum” to no avail. It’s possible they could be referring to the same person or there is misremembering on someone’s part.

Animal bone, pig teeth, and horseshoe artifacts imply that the tenants had access to animals. Informant O mentioned they kept chicken for eggs but did not recall the presence of any other animals. The pig teeth can be explained by the creation of Pettit Creek Farms in 1945, a family-owned farm with pigs, cows, llamas, and other farm animals. As Pettit Creek Farms is only five miles from Walnut Grove Plantation, it’s likely a pig could get loose and wander to the site. A horseshoe however implies they may or may not have had plow animals in addition to the John Deere tractors. These animals and equipment would have needed to be stored somewhere. It has been established that the people living here were definitely farmers, but there are not many artifacts found that relate to farming in terms of equipment or paraphernalia. Would it have been normal for tenants to have separate lodgings for their equipment? The two-story barn was big enough to have housed animals as well as all the farming gear.

Another interesting aspect of this tenant farming family was their relationship with the landowners. As Ann Cummings remembers, Eleanor Adams would visit with Skip’s mother in her kitchen. This sort of interaction implies a relationship beyond solely employer and employee. Perhaps they were friendly with each other due to close proximity in age, or that there was simply no one else around to converse with and entertain. It’s unclear whether this would have been a normal landlord-tenant relationship, as by 1925 popular sentiment of the relationship mirrored that of master and slave. Although it is said that this mindset changed throughout the years due to many viewing tenant farmers as having a fundamental place in the economic order (Buechel 1925, 336).

While oral history explained that the house was vacant in the mid 1960’s, it did not elaborate on why that would have been. None of the three informants knew exactly why the house was abandoned in the first place. In the 1960’s, mechanized farming became cheaper and more reliable (Church 2009), which could have been a possible reason for the displacement of the Adams family. The timeline of machinery taking over for human farmers lines up with when the house was abandoned.

Future directions for this study could be continued archival research. As archival research was not my main focus on this project, there might be more information available, such as a deed to the house. Similarly, if there is any way to get ahold of the negative roll number 29 from the Georgia Historic Resources offices for a clearly picture of the Adams house. There could be archival information on Eleanor Adams if she was in fact a registered nurse. Any additional information on her could certainly enhance what we already know about her story. How did the family end up at Walnut Grove Plantation, was there ever a Mr. Adams, are they still alive, and if not, where are they buried? It would also be interesting to further investigate if there are any actual studies that have been done on landowner and tenant relationship. Would it be safe to say that visitation was a one-way street, meaning Eleanor only visited the landowner’s home but the landowner did not visit the tenant house? Additional investigations to address questions relating to electricity and transportation would also be valuable.

Conclusion

The Adams family house was a residence for tenant farmers Charles Adams and his mother Eleanor Adams. It was occupied from its construction in 1910 until the mid 1960’s. The Adams were extremely poor, only retaining a small portion of their harvested crops after living expenses were deducted from their share. They were a hardworking family that had to adapt and navigate through post-Civil War reconstruction, the great depression, and several other political and economic revolutions throughout the decades. Considering what we now know about how the Adams’ lived could reshape what is known about tenancy in general. Was a vehicle common for tenant farmers to have? Was the relationship between landowner and tenant friendlier than previously assumed? Only three individuals alive today knew anything about this house and the people who inhabited it, so without their contributions in oral history, all that information would have been lost indefinitely. I’m lucky to have been able to speak to locals, work in the field and lab, and browse archives to preserve the history of this tenant farming family forever.

Acknowledgements

Thank you so much to Dr. Terry Powis for all of his knowledge, assistance, and resources in conducting this research! It truly wouldn’t have been possible without his efforts and expertise. Thank you to the Cummings Family for allowing me to do research on their property. Thank you to Kong Cheong and all the other student researchers that assisted me in the field. Thank you to George Micheletti for digitally rendering the map.

Bibliography

Billingsley, Jennifer. “Walnut Grove and the Young Family.” Etowah Valley Historical Society, May 21, 2020. https://evhsonline.org/archives/48922.

Boundless. “Tenant Farmer.” Definition of tenant farmer in U.S. History., 2018. https://oer2go.org/mods/en-boundless/www.boundless.com/u-s-history/definition/tenant-farmer/index.html.

Buechel, F. A. “Relationships of Landlords to Farm Tenants.” The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics 1, no. 3 1925: 336-42. doi:10.2307/3138901.

Church, Jason. “NCPTT | Documentation Of Tenant Farming Houses.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, October 29, 2019. https://www.ncptt.nps.gov/blog/documentation-of-tenant-farming-houses/.

Conrad, David E. “Tenant Farming and Sharecropping: The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture 2007 https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=TE009.

Cummings, Skip. “Etowah Valley Historical Society.” History of Walnut Grove Plantation 70 January 2009: 5–5.

Davis, Kenneth Penn. “The Cherokee Removal, 1835-1838.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 32, no. 4 1973: 311-31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42623406.

Dobbs, Chris. “Rural Electrification Act.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, January 29, 2016. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/rural-electrification-act.

Garrison, Tim Allan. “Cherokee Removal.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, November 19, 2004. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/cherokee-removal.

GNAHRGIS. https://www.gnahrgis.org/gnahrgis/main.do.

Hebert, Dr. Keith. “Reconstruction Bartow County Following the Civil War, Article 6 – Dr. Keith Hebert.” Etowah Valley Historical Society, April 26, 2017. https://evhsonline.org/archives/44713.

Sewell, Andrew R. “Chapter 5 Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery at the Historic Brickworks Component of 36AL480 in Leetsdale, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania,” September 30, 2004, 23.

South, Stanley. “Pattern Recognition in Historical Archaeology.” American Antiquity 43, no. 2 1978: 223–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/279246.

Woodman, Harold D. “Post-Civil War Southern Agriculture and the Law.” Agricultural History 53, no. 1 1979: 319-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3742879.

Zainaldin, Jamil S. “Great Depression.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, November 5, 2007. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/great-depression.