A man out of slavery overcoming and achieving the extraordinary.

Sponsored By: Etowah Valley Historical Society

Date: 8/28/2019

Written By:

Alexis Mazique

Chistopher Mazique

Field Supervisors:

Joe F. Head

Sam Graham

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, we are indebted to Mr. Sam Graham who rediscovered Henry Clay Smith. He not only found this forgotten son of Bartow County, he worked tirelessly uncovering facts, public records, countless number of days of searching through leads that led him to even more facts. We can honestly say that without Sam laying the foundation, this paper would not have be possible.

A special word of thanks goes to Mr. Joe Head for allowing and guiding this father-daughter team through the process of writing on Henry Clay Smith. The experience is one that has given us the opportunity to explore the rich history of this area together. We appreciate the opportunity EVHS has provided to discover this fascinating person and Mr. Head’s coaching us on how to compose this project.

We would also like to thank Mrs. Alexis Carter who words of encouragements energized us. Your work in Cartersville does not go unnoticed. Thanks for being a great role model and advisor.

Finally, we dedicate this to Henry Clay Smith for the wonderful life that he lived.

Henry Clay Smith

An Unknown Bartow Child of Slavery Destined to Diplomatic Prominence

Early Life of HCS

Henry Clay Smith (Smith) was born into slavery on January 3, 1856 in Bartow County, Georgia. i He lived with his mother, Mary Johnson a slave. He also lived with his Stepfather and half-siblings. iii His biological father is unknown. During this time, the people would have been dealing with the aftermath of the Civil War. The period for Reconstruction was beginning. It was a hard period for all southerners in this region. It could be said that for the citizens of northwest Georgia, it was a time of poverty and suffering. To be an African American during this time would have been much worse.

It seems that his family was freed when he was around 6 years old most likely due to the Emancipation Proclamation. They moved from Georgia to Chattanooga, Tennessee. At this time, Chattanooga, Tennessee was considered the negro’s Mecca. The family made this move due to opportunities in Chattanooga. He and his family worked on a farm for many years. During this time, Smith had somehow received a basic education.

Education of HCS

Smith had attended Roger Williams University in 1878 at the age of 22. iv It was noted that he participated in college debates and demonstrated his bias for democratic teachings. This was unusual because the democratic parties view towards African-Americans during this time was not favorable. They did not support the expansion of voting rights for African-Americans, and often tried to prevent them from voting.

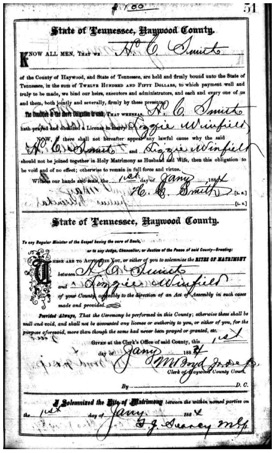

He married Lizzie Winfield on January 1, 1884 in Haywood county, Tennessee (Figure 1). v In March of 1884, Smith was the first African-American to pass the civil service examination. ii On July, 22 1884, He received a civil service position as a Clerk, Class 1 in the office of the 6th Auditor of the Treasury department in Washington D.C. It was noted that Smith received this Clerkship without the help of any politician. Smith continued to further his education at Howard University. There he enrolled in a course of Law.

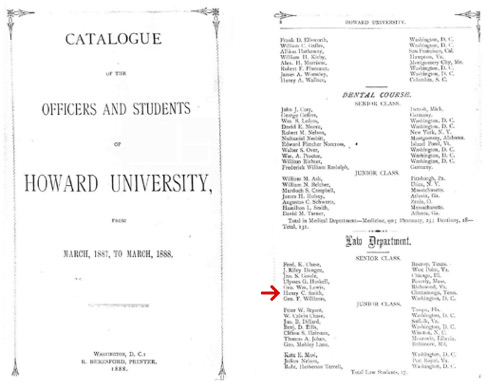

Figure 2: Catalogue of Howard University students from 1887 to 1888.

Smith completed the course of Law at Howard University (Figure 2). ix He was asked by the Auditor to resign his position as clerk but resisted. He felt as if the request was politically motivated and had nothing to do with his work performance.

Smith eventually resigned his position as Clerk on August 1 1889. x Leaving Washington, he moved back to Chattanooga to practice law and he started the newspaper, “The Agitator” releasing the first print on September 25, 1889. xi The following year he moved to Birmingham, Alabama where he continued to practice law and publishing The Agitator. He also got involved in the local politics supporting the Democratic party. He eventually became the president of the Afro-American Democratic League of Alabama. xiv

Political life of HCS

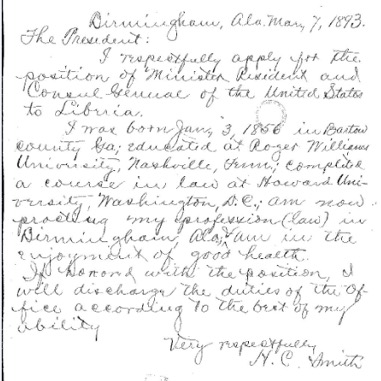

While Smith was in Washington D.C he became active in the Democratic Party. He continued to work for the Democratic party while in Birmingham as the President of the Afro-American Democratic League of Alabama. While in Birmingham, he was instrumental in aiding Congressman Turpin’s campaign. In return for his assistance, Congressman Turpin introduced Smith to President Cleveland. xiv Smith’s sound sense and diplomacy at once attracted the President. On March 7, he wrote a letter to the Assistant Secretary of State requesting to become the Minister of Liberia (Figure 3). xv

Figure 3: Copy of a letter to the Assistant Secretary of State requesting to become The Minister of Liberia. xv

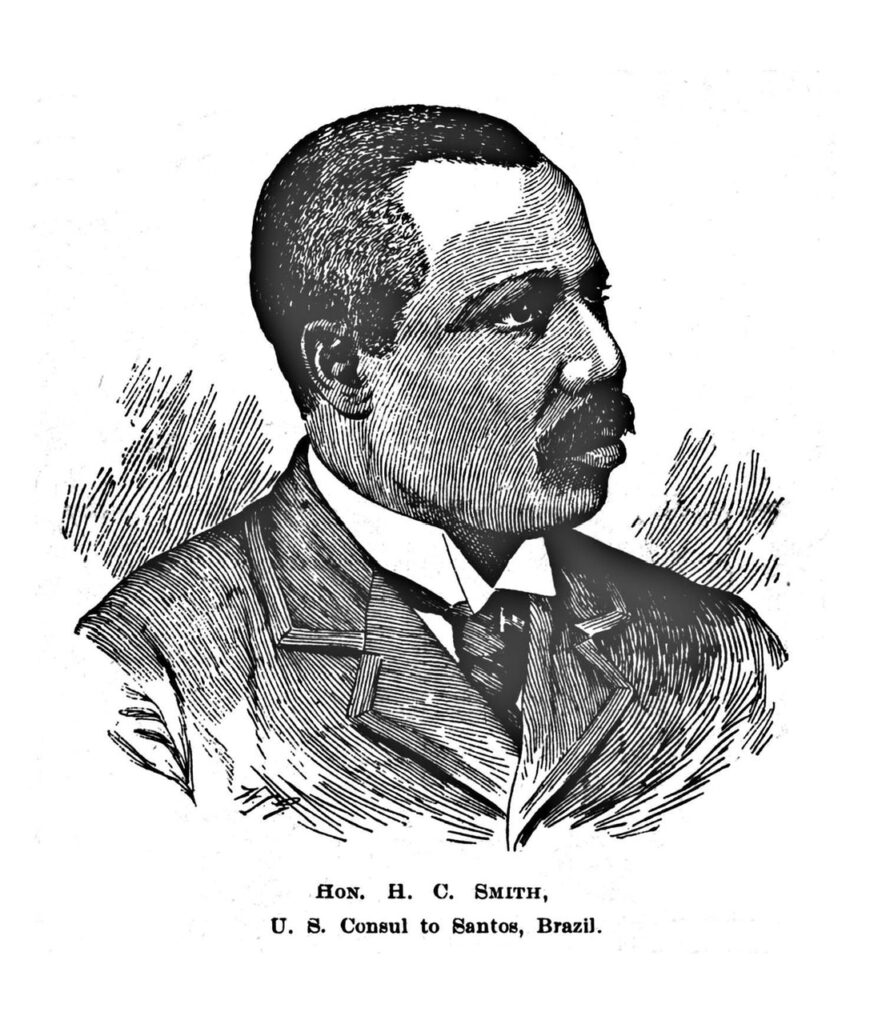

Smith sought the post as Minister of Liberia, but was later re-appointed to United States Consul to Toamasina, Madagascar. xvii He was to replace a Republican Consul, John L. Walter, from the previous administration. Smith has been an unfaltering Democrat for years, and the appointment was a recognition of his services in the democratic ranks. By July 1, 1893, he was then re-assigned to the post of Consul to Santos, Brazil. xviii The reason given for this change is that Smith’s talents would be better used in Brazil. At this time Brazil and the United States were conducting more trade. Smith was to replace Consul Berry who had gone missing for the previous three months amid reports of a yellow fever epidemic in which thousand were reported ill. Between two to three hundred people were dying each day. It was believed that Berry had ether died or fled his post. The U.S. government nor Berry’s family could contact him. Some newspapers reported that nearly all African-American appointments were to places where death awaited the appointee. Despite the risk, Smith took the assignment. He was supported by a large Democratic delegation who were determined to see the appointment go through. He had very strong political ties that supported and respected him.

Smith’s duties were consular as well as judicial. By October 1894 he had completed the “Handbook of Brazil”. He planned to be in the United States the following November to hand it in to a publisher. While serving as Consul to Brazil, Smith was praised for helping Americans conduct business. Brazil was becoming one of the most important commercial countries in South America. There were many people moving into the city of Santos. With lack of housing, opportunity was growing very rapidly in the construction industry. New railroad lines were being constructed. New roads were being built to connect the city to other places that were growing as well. Many American investors were encouraged to invest because of the high return on their money. However, the charge for docking there was extremely high. Nearly all ships were heavily fined for breaking very strict port regulation. It was reported by E.A. Armstrong, Master of the W.R. Hutchings, that all American ships had their fines remitted thanks to Smith. Smith used his skills as a Lawyer and diplomatic tact to have the fines dismissed. The United States government received many such reports praising Smith’s work as the consul to Santos Brazil.

Smith returned back to the United States sometime in November of 1894. While home, he visited many African American churches and venues. In December 1894, he gave a lecture titled “The Negro in Brazil” at the Metropolitan A.M. E. Church in Washington DC. Smith talked of seeing blacks in Brazil who were considered respectable members of society. He heard of one particular man who was born into slavery only to purchase his freedom. The ex-slave then went on to practice law. The Brazilian Bar Association there had placed a painting of him in the halls of the local court house after his death. Smith interacted and met black Captains, Colonels and Generals in the Brazilian Army. He commended the self-reliance of the black people of Brazil. Smith, on a few occasions, spoke along with Fredrick Douglas.

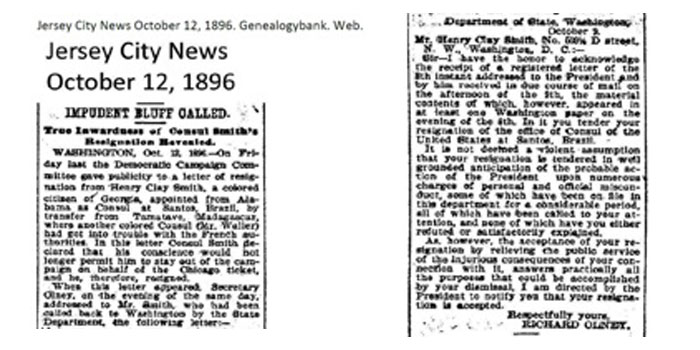

In helping the American investors avoid penalties and fees, Smith paid a high political price. It was not long before he started receiving criticisms. After the criticisms started, he submitted his letter of resignation (Figure 4). xx Smith stated in his resignation that he planned to help another Democrat in a political campaign. His resignation was accepted and Smith returned home.

Personal life of Smith

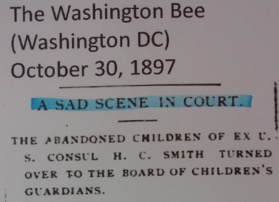

Smith and his wife had 5 children, 2 boys and 3 girls. During his last year in office, Smith was accused of not properly caring for his family (Figure 5). His wife had applied to associated charities for aid. On October 30, 1897 the courts removed the 4 children, the oldest had been removed a few days before, and sent them to live with his wife’s family in Brownsville, Tennessee. After his wife left him, Smith relocated to New York. The judge stated to the Washington Bee that it is a Godsend that we have such an institution to take care of the children. It was a sad scene that was keenly felt by him.

Religious life of Smith

Smith became a Baptist Minister and was very active with the concerns of the African-American community. He worked with other religious and civil leaders to promote freedom and equality. Many of his lectures were in Churches involving the development of the Black man as well as equality and the race problem. From the beginning Smith realized that the land in which they lived was controlled by the white race. He also believed that the black man would be respected and eventually treated as equal by demonstrating his hard work and intellect. The church was a place where the black community could come together in a welcoming environment to improve the lives of many African-Americans.

He soon helped to establish “The National Mutual and Industrial Order”. xxi The purpose of this educational organization was to provide job skills to African-Americans who wanted employment opportunities. During this time many African-Americans were beginning to migrate to the north in search of employment and better treatment by society. Training was provided in the area of Domestic help, Butlers, Chauffer and other careers. Offices were established through-out the northeastern and southeastern states.

Smith also helped found “The New York State Association of Colored Voters” (NYSACV). xxii This organization held meetings that were closed to the public. The politicians became uneasy by this idea and began to express concerns. The NYSACV wanted to collect the black vote and support the political party that addressed most of the black community’s concerns. This was the start of a shift in Smith’s thinking and acting. In the past he had only supported the Democratic party. In doing so, he was given support in return. Now he was promoting that both parties should work to get the black vote. The NYSACV insisted on conducting the meeting behind closed doors to allow the participants the opportunity to freely express their views and concerns. Smith toured the state and organized more than forty-five cities and towns. This took him through twenty-five counties. He was targeting areas where there were large numbers of black voters. He had to now work with people who were strictly Republicans supporters. He had to convince the voters to be willing to support the Democratic party if they were willing to agree to the NYSACV’s proposal. They were able to deliver over 20,000 votes for that local election. At this time, there existed other political organizations that worked with ether the Democratic or the Republican parties. The New York State Association of Colored Voters said that they would no longer consistently support only one party.

The other important issue that NYSACV addressed was the education of black voters. The idea was to educate the community on the value of wealth. NYSACV believed that by placing importance on maximizing the wealth in the community will lead to a new found self-respect and result in being respected by other races. The condition of the whole community is more important than the poor people who were looking to sell their vote for financial profit. The condition of the whole community was more important than any wealthy black person who despised the poor. There was also lots of emphasis placed on respecting the black woman in particular. It was clear that NYSACV were not against any political party. The philosophy was intended to improve the lives of all in the black community by pooling together the voting power. It was hoped that the actions of NYSACV would result in equality in the northern states as well as southern states.

Smith became president of the Staten Island Domestic Training School. xxiii The school offered a six-month training program to prepare black men and women with the skills needed to work after migrating to the north. It was meant to address the problems that many African-Americans faced after migrating to the north only to find it difficult to find gainful employment. The school had multiple campuses in the north and the south. Some of the topics covered in the program included: How to select good meats, fruits and vegetables, basic arithmetic, cooking, how to prepare drinks, house repair, cleaning, hygiene, reading, spelling, writing and black history in America. Smith used his alliance with both African-Americans and whites to solicit financial assistance in the form of investments in the school. He skillfully explained how investing in the school would benefit all members of society. He readily worked with both black and white churches to ask that collections be taken up to support this cause. The funds were used to establish buildings, dormitories and schoolrooms.

Late in 1902, Smith traveled to Long Branch, New Jersey where he acted as a delegate to the “Afro-American Baptist Association” xxviii. Three days later, he was having supper with friends at a boarding house when he experienced chest pains and excused himself. He was later found dead in the back yard of the boarding house. The cause of death was due to an affection of the heart. His funeral was held at the Second Baptist Church in Eatonton New Jersey. He was remembered as a scholar of remarkable intellectual ability, being at one time consul to Brazil under former President Grover Cleveland. He was the master of several languages. He was laid to rest in White Ridge cemetery.

The contributions of Smith

With the passing of to the Emancipation Proclamation, many African-Americans began to discuss the best path forward. Two views rose to the top of the discussion. The views of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois were very popular. Booker T. Washington believed that if the black people would demonstrate their excellence through work and character, then the white man would accept them. On the other hand. W.E.B. Dubois believed that African-Americans should protest for equal rights. This was a huge debate between peace and protest.

Early in Smith’s life, he seemed to practice the philosophy of Booker T. Washington. This was demonstrated in his decision to join the Democratic party. He formed political alliances with powerful whites. This may have enabled him to solicit the backing and support needed to allow him to be appointed to public office. He also founded “The Christian National Mutual and Industrial Order.” The purpose of this organization was to provide training to all black people who wanted various jobs in domestic or professional positions.

Later in Smith’s life he seemed to practice the philosophy of W.E.B. Dubois. This was demonstrated by his insistence that political parties work to get the black vote. He also helped form a secret political society that discussed and proposed topics that should be addressed before the black vote would go to them. The formation of this secret society made many whites very nervous. He also was the Director of the New York State Association of Colored Voters.

The New York Times stated, “he had succeeded, after making a tour of the state, in organizing in more than forty-five cities and towns covering twenty-five counties, where there are colored voters.” xxii His association is like the Italian, German, and Irish associations. “Our meetings are all secret, because we discuss and talk over matters that could not very easily be discussed in public. We have not yet determined what party we will support. That will be for the convention to determine.”

Many politicians were suspicious of the association due to the secret meetings and the constant change of party support. When Smith started the organization, he pointed out that the organization had no grievances against any political party. ”If this is a Democratic platform, “said Mr. Smith, “make the most of it. If it is Republican, make the most of it.” xxiv He believed that if it was not for the laws of oppression that there would not be growth where there once was idleness and poverty. “The salvation of the black man is in his own hands.” xxiiv Smith states.

Bibliography

i NARA Record Group 59, Box 80, letter dated March 7, 1893, HCS to President Grover Cleveland.

ii The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee) July 29, 1884, Newspapers.com. Web.

iii Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA

iv The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee) July 29, 1884, Newspapers.com. Web.

v Marriage record, State of Tennessee, Haywood County, January 1, 1884, Ancestry.com. Web.

vi Pittsburg Dispatch (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania) July 24, 1889, Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. Web.

vii Ibid.

viii Chattanooga Daily Commercial August 7, 1885, Chattanooga Newspapers, chattanooga.advantage-preservation.com. Web.

ix Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Howard University from March, 1887 to March, 1888, Howard University Catalogs. Web.

x Pittsburg Dispatch (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania) July 24, 1889, ChroniclingAmerica.loc.gov. Web.

xi Jacksonville Republican (Jacksonville, Alabama) October 12, 1889, Newspapers.com. Web.

xii Montgomery Advertiser January 13, 1893. Newspapers.com. Web.

xiii Huntsville Weekly Democrat (Huntsville, Alabama) August 20, 1890. Newspapers.com. Web.

xiv The Montgomery Advertiser January 13, 1893. Newspaper.com. Web.

xv NARA Record Group 59, box 80, letter dated March 7, 1893, HCS to President Grover Cleveland.

xvi The Brewton Leader (Brewton, Alabama) April 4, 1893. Newspapers.com. Web.

xvii NARA Record Group 59, Box 28, Card Record of Appointments.

xviii NARA Record Group 59, Box 28, Card Record of Appointments.

xix Alabama Beacon (Greensboro Alabama) June 28, 1893. Newspapers.com. Web.

xx Jersey City News October 12, 1896. Genealogybank. Web.

xxi Richmond Planet (Richmond, Virginia) August 28 1897. Virginiachronicle.com. Web.

xxii New York Times, July 25, 1900. Newspapers.com. Web.

xxiii The American Kitchen Magazine April-September, 1902. Google Books. Web.

xxiv Denver Rocky Mountain News, March 5 1902. ChroniclingAmerica.loc.gov. Web.

xxv Long Branch Record (Long Branch, New Jersey) October 31, 1902. Newspapers.com. Web

xxvi Long Branch Record (Long Branch, New Jersey) November 7, 1902. Newspapers.com. Web.

xxvii The Washington Bee (Washington DC) October 30 1897. Newspapers.com. Web.

xxviii Long Branch Record (Long Branch, New Jersey) November 7, 1902. Newspapers.com. Web

xxiv The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) August 8, 1900. Newspapers.com. Web

xxiiv The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York) August 8, 1900. Newspapers.com. Web