Corra Harris: Forgotten Contradictions

A Historical Analysis Revealed among Personal Letters and Archaeological Finds

Martha Berry (on the left) and Corra Harris (on the right) at In the Valley, 1922

Jordan Gentry

Honors Capstone Project, Kennesaw State University

Faculty Advisor: Dr. Terry Powis

EVHS Field Supervisor: Mr. Joe F. Head

Abstract

This paper is the first to report on the findings of the historical archaeological research done on the property and an examination of a collection of newly discovered personal letters and legal documents of Corra Harris . The purpose of this research was to compare Corra Harris’ public ideals to her private ones in hopes of understanding why these two personas might differ as suggested by Olgesby and Badura (2008, 2000). Using previous research on Harris’ writings and comparing those findings to the personal letters, legal documents, and artifacts analyzed for this paper, this study found that ideals Corra Harris portrayed in her writings differed wildly from the beliefs she held in her personal life. This paper suggests that this is possibly due to the fact that Harris’ writings helped her maintain financial security; therefore, she continued to let her writings express different ideals from her personal beliefs, so that she could continue to be successful.

Introduction

Corra Harris was a prominent writer in the 1900’s whose works once captured a national audience, but have since fallen into the obscurity of time. Interest in Harris and her property of which she called, “In the Valley, re-emerged after local philanthropist, Jodie Hill donated the estate in 2008, to Kennesaw State University. The property is located in Rydal, Georgia, in Bartow County. The home is said to have once belonged to Chief Pine Log, although no record of him still exists. When Harris purchased the property, it had only a single log cabin; she expanded the log cabin and added several buildings, including the library that she worked in. KSU intended the property to be used for research and field experience for students. Dr. Powis along with many KSU students conducted an archaeological survey of the property during the field season of 2010-2012.

However, in 2014, controversy surrounded Harris and her home after KSU removed an art piece intended to be part of an exhibition at the Zuckerman Museum of Art. The president of the college at the time, Dr. Papp, stated that the piece did not fit in with the overall celebratory theme of the exhibition. The people opposed to the removal called the removal of the art piece a form of censorship and an attempt to ignore some of the uglier sides of Harris’ and the property’s history. After the controversy, most of the field work and research came to a halt. This paper presents the first analysis of artifacts recovered during the excavations at the Corra Harris site. This paper also presents the first analysis conducted on letters and legal documents on loan with the Etowah Valley Historical Society located in Cartersville, Georgia. This study seeks to compare the ideals expressed in Harris’ writing to her private ones in order to understand why these two personas might differ as suggested by Catherine Olgesby and Catherine Badura (2008, 2000). Using previous research on Harris’ writings and comparing those findings to the personal letters, legal documents, and artifacts, this study did find that beliefs Corra Harris portrayed in her writings differed drastically from the beliefs she held in her personal life. This paper suggests this may be due to the fact that writing helped Harris maintain financial security as well as providing a solace for her when life seemed unbearable; therefore, she continued to let her writings preach a doctrine she no longer believed in so that she could continue to succeed.

A Short Biography of Corra Harris

Born in March of 1869, Corra Harris grew up on Farmhill Plantation in Elbert County, Georgia, as the eldest child of Tinsley Rucker White (1844-1930) and Mary Elizabeth White (1846-unknown). She received her education at home from her mother and at Elberton Female Academy, a local school for girls. When she was fifteen, she met her husband, Lundy Howard Harris (1858-1910), after moving in with her uncle in Banks, Georgia. She and Lundy married on February 8th, 1887 and their daughter was born in December later that year; Faith was Harris’ only child to live past early childhood. Her other two children died at infancy. Lundy worked as a Methodist circuit rider before accepting a position at Emory as a Greek professor in 1888. In 1898, Lundy left Emory after suffering a mental breakdown due to his alcoholism and bouts of depression.

The Harris family moved to Rockmart, Georgia, after Lundy received a position teaching at the Rockmart Institute. It was here that Corra Harris wrote the letter to the New York Independent Magazine in defense of the lynching of an African American male in Newnan, Georgia. Despite the contents and the message in the letter, the editor of the magazine found the letter so well written that he published it in the magazine in 1899. This was the article that began her writing career. After the publishing of that letter in 1899, Corra began regularly writing articles, editorials, and book reviews for multiple different news outlets. Shortly after this, Lundy accepted a position as Secretary of Education of his church and the family moved to Nashville, Tennessee.

Corra continued her writing in Nashville to help support her family financially. She published her first novel, Circuit Rider’s Wife, in 1909, a partially autobiographical novel. Lundy continued to suffer from depression, and in 1910, he committed suicide by overdosing on morphine at the Anthony’s Farm in Pine Log, Georgia. Following his death, Corra purchased her home that she called In The Valley located in Rydal, Georgia, close to where Lundy died. Here, she produced most of her literary work, writing serials, editorials, book reviews, novels, short stories, et cetera. Harris wrote nearly a thousand articles for various newspapers and magazines. She also published nineteen books, two of which became movies (Circuit Rider’s Wife and My Book and My Heart) and one which she coauthored with her daughter Faith shortly before Faith’s passing in 1919 from an unknown cause. She served as the first female war correspondent in 1914 for the Saturday Evening Post, visiting London and Paris during the first world war.

Harris’ literary career began to come to an end when her health began failing her in the 1930s. She passed away in Atlanta, Georgia, after suffering a heart attack in 1935. Harris is buried at her home in Rydal, Georgia. She had a chapel built over her grave site. Corra Harris’ home, In the Valley, after suffering neglect from her family, Jody Hill, a prominent insurance executive in Bartow County, partially restored the property before he donated it to Kennesaw State University in 2008.

Corra Harris in Writing

Though Harris held a national audience for nearly two decades, there has not been a lot of research done on her. Previous research on Harris’ writings was used as comparison to the research conducted by this study on Harris’ private life. This literature review provides the analysis conducted on Harris’ writing.

Literature Review

Karen Coffing wrote an article analyzing ideals expressed by Corra Harris in her articles in the Saturday Evening Post from 1900-1930 (1995). The Saturday Evening Post was considered the most widely read magazine of Harris’s time. With its national audience, the Post helped Harris gain financial security. Her articles focused on preserving the Cult of Domesticity, a belief that women were morally pure and contributed to society by staying in the home. For Harris, this idea was especially true for Southern white women who were seen as sexually pure, delicate, and virtuous. Coffing state Harris believed the purpose of a woman was to provide a “refuge for men who had to deal with an impure world” (1995, 368). Harris believed that marriage was the only option for women. In her writing, she “heavily romanticized the relations between men and women, and avoided any overt discussion of possible marital or social problems for women” (Coffing 1995, 385).

While Harris supported woman’s suffrage, she believed that it should be attained through the husband, meaning that Harris believed that women should encourage their husband to work for women’s suffrage rather than trying to get it themselves. She hoped that women would use the vote to maintain the home, stating that she “hoped that women could use the vote to bring feminine virtues into the public life without compromising their position within the home” (Coffing 1995, 388). Catherine Badura examines Harris’ views on women’s suffrage and modern feminism by comparing Harris to suffragist Rebecca Latimer Felton and anti-suffragist Mildred Lewis Rutherford in her article “Reluctant Suffragist, Unwitting Feminist: The Ambivalent Political Voice of Corra Harris” (2000). She argues that Corra Harris represents middle-class, white women who did not take a stand on suffrage and feminism.

Even though she called herself a “regrettable suffragist” in her writings, Corra Harris’ ideology aligned more with socially conservative antisuffragists. Harris believed that that the public sphere de-sexed women and that activism in this sphere made them unfit for their primary role in life. Although, when asked to take a stand, she supported suffrage, Harris said that women paid a price for it; the more political rights they gained, the more they lost in their private life. Badura states that Harris believed “competition with men in the public sphere… would prove more injurious to women than anything they had suffered in the private sphere” (Badura 2000, 401). Badura and Olgesby argues that she contradicts these ideas in her personal life by having economic independence and advising her own daughter in a letter not to marry and have children (2000, 2008). In addition, Harris also remained widowed for 25 years. Badura states she “lived at odds with an image she grew wealthy and famous for promoting” (2000, 406).

In addition to writing for the Saturday Evening Post, Harris also wrote for the magazine the Independent. In the article “The Early Literary Criticism of Corra Harris,” C.H Edwards analyzes Corra Harris’ critical articles she wrote about modern fiction for the Independent in 1900 to 1910 (1963). Corra Harris denounced the rising schools of realism and social criticism within novels. She held romanticism to be the true purpose of fiction. Harris discusses two ideas in her articles: realism and literalism. Realists bring imagination into a novel, while literalists report facts. Good novels are combinations of both. Edwards says Harris believed “Life must be seen through the eyes of the romanticist to make it acceptable material for novels” (1963, 450).

The main criteria for determining if a novel is good or not is the morality of the characters. A good novel has moral characters and a bad novel has immoral characters. Immoral characters come from immoral authors. Harris believed that these types of novels corrupted the minds of young girls. She disapproved of the “muck-rakers” and sociological realists. Some of these included Frank Norris, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair. Edwards concludes by saying, “By rigidly requiring literature to be romantic and moral when many authors were attempting to portray a society which was anything but romantic and moral…, Mrs. Harris was definitely at a disadvantage in trying to say anything of permanent value about the fiction of her time…she lacked the education and social enlightenment which could have produced critical perception on a par with that of writers from other sections of the country” (1963, 455).

Results

This study sought to compare Corra Harris’ public ideals to her personal ones, and to understand why these might differ. Specifically, the researcher compared the archaeology and the historical documents to analyses of Harris’ writing looking for possible contradictions. This research was done with the help of Dr. Terry Powis and Joe Head.

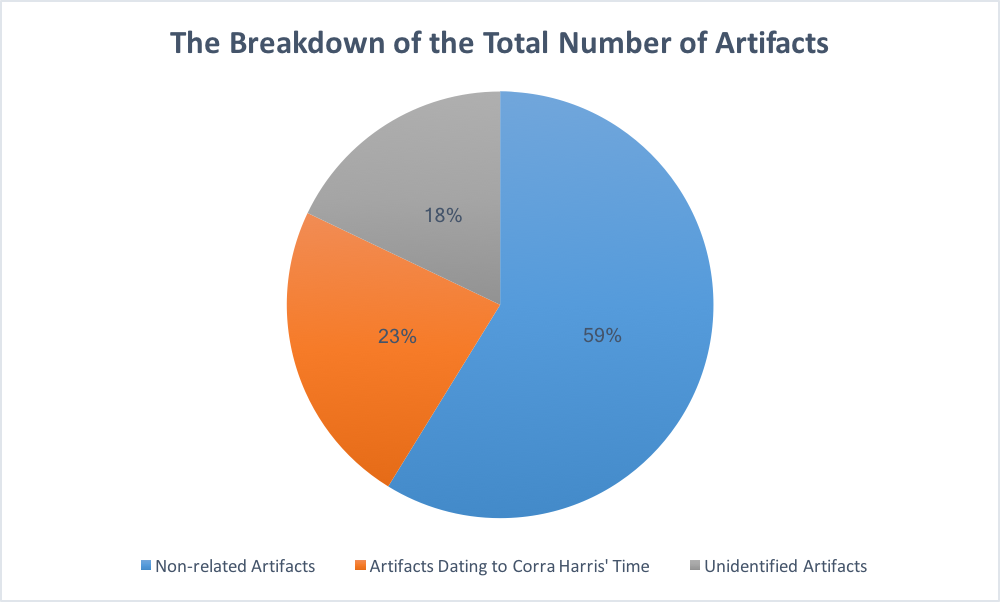

Figure 1: The breakdown of artifacts from ITV

Archaeological Results

Total of 724 artifacts were recovered from the Phase I and Phase II excavation done at ITV. Of those artifacts, 160 of them, 18%, could not be identified (see figure 1). This is due to issues Figure 2: The breakdown of artifact related to Harris’ time

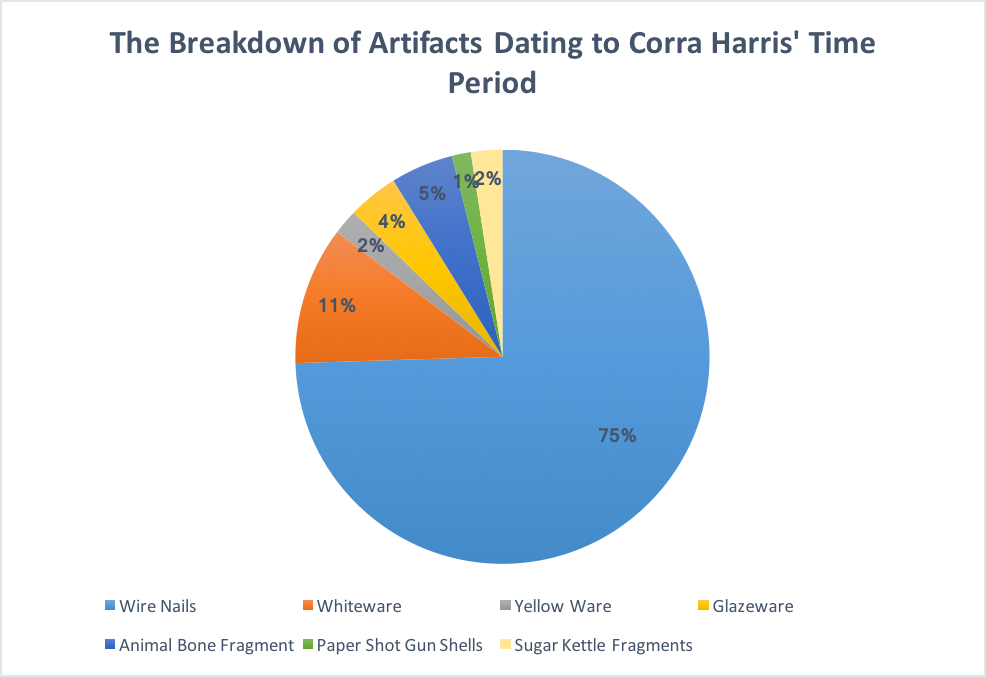

Figure 2: The breakdown of artifact related to Harris’ time

during identification such as artifacts being rusted beyond recognition. A total of 206 artifacts, 23%, could be identified as being related to Corra Harris’ time period (see figure 1).

The artifacts related to Corra Harris include wire nails, white ware, yellow ware, paper shot gun shells, glaze ware, a set of keys, horseshoes, mule shoes, and sugar kettle fragments. A total of 76% of the artifacts related to Harris’ time frame were wire nails (see figure 2). Wire nails date from 1890s to present (see figure 3). It is not surprising that a large number of nails were found; Corra Harris had lots of construction going on while she was expanding her property (EVHS Letters 11/9/1913).

Figure 3: A sample of wire nails found at ITV

The second greatest number of artifacts related to Harris’ time is white ware fragments. White ware fragments make up about 11% of the artifacts (see figure 2). White ware is white earthenware household table ware that has a clear glaze; it dates from the 1820s to the 1900s The majority of the white ware was undecorated white granite china which dates from 1845 to the present (see figure 4, bottom right).There were a few fragments recovered that were decorated. One piece was identified as Blue Transfer ware, a blue underglaze pattern on top of a piece of white ware. It dates to 1820 to the 1900s. Another fragment was identified as sponge ware, a technique that developed in the 1830s (see figure 4, bottom left). In addition to the white ware, fragments of yellow ware were also recovered (see figure 4, top right). This type of ware dates from 1820s to the 1900s and was popular in the Northeast. The yellow color is caused by impurities in the clay.

Figure 4: A sample of the ceramics found at ITV.

Fragments of glaze ware, identified as alkaline glazed stone ware (or crockery), were also found during excavation (see figure 5). This type of glaze developed in the 1800s in South Carolina and spread as far north as North Carolina and throughout the entire southern row of states into Texas (Greer 1981, 202). Alkaline glazes remained popular well into the 20th century in rural parts of the South due to the fact that all of the ingredients were fairly inexpensive to make and widely available in the South.The pots with alkaline glazing normally served a utilitarian purpose since the pots were very durable and hard (Greer 1981, 202). Also common in the South were the sugar kettles found on the property. Sugar kettles were used for sugar production on plantations during the 18th and 19th century. Harris grew up on a plantation; therefore, it is possible that Harris kept the kettles as heirlooms.

Figure 5: A sample of the type of glaze ware found at ITV

Aside from ceramics and stoneware, animal bone fragments and paper shot gun shells were found during excavation. Corra Harris was known to have farm animals on the property as well as horses and mules which explains why animal bone fragments along with horseshoes and mule shoes were found. A total of three paper shot gun shells were found dating to Harris’ time period. It is unknown if Harris owned a rifle; however, it is possible given the time and place Harris lived in. Each one of the paper shot gun shells was identified as a different type. One was a Winchester New Rival dating to 1901; another was a U.M.C Co. 16 New Club Star dating to 1902-1910. The third one was a U.M.C No. 12 dating to 1902-1910 (Headstamps 2016).

For the future, further excavation in different areas of the property could produce more artifacts as well as different types of artifacts related to Harris’ time period.

The Legal Documents A collection of over a hundred legal documents saved by the Akin family, who were family friends of Corra Harris, dating from 1911 to 1925 was analyzed for this project. Many of the documents were drafted up by Paul Akin, a close friend of Harris’. Paul Akin acted as Harris’ financial advisor after her husband died. He assisted her in buying her home in Rydal, Georgia, helped her prepare her taxes, drafted up the loan agreements, and offered her financial advice. The documents give major insight into Harris’ finances and her personal interests.

Contained within the collection are over a dozen loan agreements between Corra Harris and various people within the county. She gave out small loans ranging from a couple hundred dollars to a few thousand dollars to people in Bartow County. She charged between 7-8% interest per annum, over a span of 3-5 years. It is unclear why these people would choose to take a loan out from Harris rather than from the bank. It is assumed that these people most likely could not get approved by the bank. Therefore, they chose to go to Harris.In addition to loan documents, found among the documents were carbon copies of letters sent to Harris as well as hand written letters sent by Harris. In 1912, she showed an interest in municipal elections after moving to Bartow County. While the initial letter sent by Harris was not found in the collection, there was a letter sent by Mr. Akin responding to Harris’ inquiry. He says:“I am not sure as to whether you wish to know how women citizens of a municipality could become qualified voters in municipal elections, or whether your inquiry is directed to the qualifications of women in the county in State and County elections…I know of constitutional prohibition by the United States against woman suffrage…You readily see that in order that women may become qualified voters, it would be necessary to first amend the Constitution by removing the limitation to males.” (EVHS Letters 5/ 23/1912)

While Harris’ letter has not been found, Mr. Akin’s response shows Harris had an interest in politics and specifically an interest in how women could vote. Harris showed an interest in politics again in 1920 after the passage of the 20th amendment when she was asked by Irving Fisher, an American economist, in a telegram to sign her name in support of the U.S joining the League of Nations. Harris did elect to have her name included on the list, stating that she supported James M. Cox, the democratic nominee, in the 1920 presidential election (EVHS Legal Documents 10/1920).

In 1918, Corra wrote a letter stating she wanted to claim ‘head of the family’ on her taxes and receive the tax break for it. At first, Akin responded to the request by stating that he did not think her contributions to her family were enough to qualify for the tax break. However, he changed his opinion after Harris wrote a letter detailing exactly why she should be able to claim it on her taxes, stating that she had performed all the duties expected of the head of the family (EVHS Legal Documents). Her sister and nephew were dependent upon her, in addition to her daughter. She also covered all of her family’s medical expenses; the receipts of these medical expenses were included in the documents. In the tax records, it shows that Harris did claim ‘head of the family’ every year after 1918.

The collection of documents contains a lot of information that could not be directly related to the topic of this paper; however, they still contain a lot of information that could be further analyzed.

Letter Results

A total of 16 letters between Corra Harris and Joy Akin dating from 1913 to 1925 were analyzed for this project. From these letters, Harris’ innermost feelings were revealed. Harris sent the majority of the letters from places she was visiting in addition to her home ITV. Some of these places include North Carolina, Tennessee, and New York. Harris even sent a letter to Mrs. Akin from the boat she travelled on when she was on her way to Europe to report on the war. Harris enjoyed traveling, and she often travelled by herself. In one letter she wrote to Joy, she talks about the Grove Park Inn in North Carolina, a place she visited multiple times:

“This is the loveliest place I ever saw, and I have been treated with so much tenderness, consideration, and fed in admiration that you may expect to see me a typical authoress, stuck up, inflated by my own impertinence, and thoroughly unbearable.” (EVHS Letters 8/26/1921)

In her letter, Corra Harris confides in Joy about her bouts of depression and anxiety attacks. In one particular poetic letter to Joy, she says

“In these days upon the earth, I sometimes lose the witness of some great spirit, that confirmation of glory to come. It is as if I were about to die without dying. I am homesick for I know not what far beyond the realities of time will serve. I am a beggar there beneath the “gate of our pearl”.” (EVHS Letters 11/9/1913)

This letter was written shortly after Harris had purchased her home in Rydal, Georgia, about three years after her husband had passed away. Much of that letter expressed feelings of doubt: doubts about her faith, doubts about how her life is supposed to go et cetera. In another letter written years after her daughter Faith and her sister Hope had passed, Harris says

“After several weeks of pain and depression, I came down the last three days of the old year with one of my attacks, by yesterday however, (?) able to be in the study to begin the new year properly at work, which for me has been the one excitement against pain, grief, anxiety, and loneliness.” (EVHS Letters 1/2/1924)

She also talks in that letter about how lonely she was in the later years of her life.

“I spent a Christmas so quiet it was fuller than usual of memories and silence. No one here except Wallace who came out one day to take some pictures for “My Book and Heart”.” (EVHS Letters 1/2/1924)

A recurring theme in all Harris’ letters in the solace she finds in both her writing and her home in Bartow County. She suffered a lot in her life, watching as all the people she loved died before herself. Harris wrote a letter to Joy discussing the immense sadness she felt as Faith lay on her death bed:

“This is just a little note to say that Faith arrived safely Sunday and that she seems to be doing nicely. She is patience and cheerful and has a good appetite and what more could you ask of an invalid …I went to write I long letter, but I can’t without crying or saying things I ought not to say.” (EVHS Letters 7/28/1916)

Working provided a distraction from her grief. She often talked about working to keep from falling into despair:

“I worked hard all that day to keep from thinking. Late in the afternoon, I went back to the house and dressed myself in memory of Faith, who would have wished me to look well on such an occasion.” (EVHS Letters 3/20/1920)

This letter was written about her birthday, a little less than a year after Faith died. She talks in this particular letter about working to keep from feeling lonely and sad. Harris spent this birthday alone, a stark contrast to her birthday the year before, she says, where Faith came to visit, and they had a lively evening. That was the last time Faith ever visited Harris’ home, In the Valley. She remembers the night fondly, but it brought her sadness to remember.

Toward the end of her life, Harris continued to find peace in her writing, in travelling, and in her home, In the Valley, until she became too sick to write and travel. These letters give a glimpse into the emotional turmoil Harris suffered throughout her life and how she was able to continue living despite the large presence of hardship and grief in her life.

Discussion

Badura states Corra Harris “lived at odds with the image she grew wealthy and famous for promoting” (2000, 406). In her writings, Harris promoted the preservation of the Cult of Domesticity. The Cult of Domesticity is a social system that prevailed in the nineteenth century that stated that a woman’s purpose was limited to caring for the home and family. However, in her personal life, from this research and the research of Olgesby and Badura, Harris’s actions and lifestyle do not give any indication that Harris still supported this social system in the later part of her life (2008, 2000).

The Cult of Domesticity was an idea that Harris most likely grew up believing in. She grew up on a plantation in the South where this belief was most prevalent. She had a limited education at Elberton Female Academy, a local school, in addition to the lessons her mother gave her at the home. This education was mostly remedial and focused more on teaching her how to maintain a home than actually educating her. However, her life experiences mostly changed her belief. She married her husband, Lundy Howard Harris, when she was only 15 years old. While Harris spent the first part of her marriage playing her role as a homemaker, very soon Lundy proved himself incapable of fully providing for his family due to his battle with depression, alcoholism, and addiction. Lundy gained and lost jobs frequently in his life, and therefore, he was unable to keep his family financially secure. One of the main reasons Harris began to write for newspapers and magazines was for financial security. This probably was the beginning of her view on women’s role in society changing.

In her writing, she “heavily romanticized the relations between men and women, and avoided any overt discussion of possible marital or social problems for women” especially in her book A Circuit Rider’s Wife. (Coffing 1995, 385). A Circuit Rider’s Wife is a semi-autobiographical work which follows the life of a woman and her husband during his missionary work. In A Circuit Rider’s Wife, she does not discuss any martial issues between the couple; however, Harris’ own marriage was not a fairytale. Issues filled her marriage mostly resulting from Lundy’s mental illnesses. She often expressed in her writings a belief that marriage was not an option for women; it was a requirement. A woman could not fulfill her purpose in society without marriage.

Yet, Harris remained widowed for 25 years and encouraged her own daughter Faith not to marry in a personal letter sent in 1911 (Olgesby 2008). On this topic, Catherine Olgesby states in her biography of Corra Harris, “She wanted Faith to follow in her footsteps as a writer, but to do so without the attendant distractions of husband and family. Corra knew from personal experience how difficult it was to have both a family and a career” (Olgesby 2008, 41). Harris did not want Faith to live the life she heavily preached in her writings. She attempted to push Faith to become independent and self-reliant just like Harris did after Lundy’s suicide.

When it came to women suffrage, Harris called herself a “regrettable suffragist”; however, in her writing, Badura argues, Corra Harris’ ideology aligned more with socially conservative antisuffragists; she believed that activism in the world of politics would make them unfit in their role as a housekeeper (2000). In 1908, Harris wrote “prefer to remain the victim of man’s love and injustice rather than compete with him politically, face his temptations and risk the chance of being elected to some indelicate office like that of sheriff” (Badura 2000, 400).

Yet, in 1912, eight years before women got the right to vote, Harris showed a personal interest in municipal elections after moving to Bartow County, Georgia. In a letter from Paul Akins responding to Corra Harris, he tells her that there is a “constitutional prohibition by the United States against woman suffrage” and “that in order that women may become qualified voters, it would be necessary to first amend the Constitution by removing the limitation to males.” (EVHS Letters 5/23/1912). It should be noted that unfortunately, the letter sent to Mr. Akins by Harris was not found among the collection of documents analyzed for this study.

However, this letter shows Harris taking an interest into the world of politics, the same politics she said women should stay out of. It was not until 1914 that Harris publicly expressed any amount of support in suffrage movement, and when she did, she stated that she had serious reservations about how active women were becoming in the political sphere. Harris told a reporter in 1914, “I believe in votes for women, but I do not believe . . . in the anti-civilized, caveman-like suffragette who is making entirely too much fuss in this city [New York]” (Badura 2000, 401; Harris 1914). Harris also wrote that even though she believed the suffragists to be doing some good, she believed that good they are doing is bad for them, “profaning to some essential decency and delicacy of womanhood” (Badura 2000, 402).

Despite saying that women suffered when they become politically active, Harris takes an active role in politics when Irving Fisher, a prominent American economist in the 1900s, sends her a telegram asking her to sign a petition for the New York Times in support of the League of Nations. Harris agreed to have her name included stating that she supported James M. Cox, the democratic nominee, in the 1920 election. This was the first election that women had the right to vote in, and Harris was already participating in political activism and planning on being a voter. By participating in the election, again, Harris goes against the belief in her writing that activism in the political sphere would make her unfit to do her “primary” role in life.

Corra Harris was an independent woman despite anything she might have advocated for in her writing. She was financially independent; in 1920, she filled out the tax form for people whose income is more that 5,000 dollars (EVHS Legal Documents). In today’s economy, that would equal about an income of 100,000 dollars. The archaeology done on the property indicates she lived a typical middle class life despite making enough money to be considered wealthy. The documents and the archaeology seem to point to Harris using her money to care for people rather than trying to live a lavish lifestyle. She financially supported her daughter Faith and her husband Harry Leech, who also proved to not be able to always provide for his family. Harris supported her father while he was sick, paying for his nurse and hospital expenses. Her sister Hope and her son also required Harris’ support after Hope’s husband died. In addition to helping her family, Harris also helped the people in the county by giving out loans. It is assumed that these people went to Corra for help when they couldn’t secure loans through the bank. The collection of documents contained nearly a dozen or more loan contracts between her and various people in town.

Harris saw herself as head of the family, a title that use to be reserved for males only. In 1918, she wrote a letter to Paul Akin detailing why she should be able to claim head of the family on her taxes, stating that she had performed all the duties expected of one with the title: “I do not understand it to be the government purpose to penalize me with a heavier tax, because my husband is dead…” (EVHS Letters 2/11/1918). Harris clearly felt that she had earned the title and that she should not be forced to pay a higher tax because her husband was dead. She did end up claiming head of the family on her taxes that year and every year that followed.

So, in summary, Badura (2000) and Olgesby (2008) were correct in their assessment of Corra Harris’ contradictory life. Harris lived a life completely at odds with the ideals she expressed in her writing. After analyzing the artifacts, letters, and documents, one theory for why Harris would choose to continue to advocate for an idea/ belief system she no longer believed is because preaching those ideas in her writings proved itself to be successful. When she did venture into different topics in her writing, she was unsuccessful. In 1914, when Harris was sent over to write about the women’s effort in the war, she learned upon her return that those articles hadn’t been popular. In fact, when she asked to return, the Saturday Evening Post decided to send another reporter in Harris place. Not only did she waste her time, but she also didn’t make very much money from that.

Harris’ first priority was financial stability for her family. Her husband struggled to keep the family economically secure, and after his suicide, it was up to Harris to keep the family from destitution. It is possible that she continued to write what she knew would sell even after her personal views changed to maintain that financial stability. Harris’ writing was also a solace for her. It was what she had when she felt she had nothing else left in her life to keep her motivated. The letters to Joy reveal that Corra suffered from loneliness, depression, and anxiety attacks. She would use work as a distraction from the negativity in her life. Corra lived to see her husband die, all of her children die, her father die, and her sister die. She looked forward to writing which she says in one letter was “the one excitement against pain, grief, anxiety, and loneliness.” (EVHS Letters 1/2/1924). Harris most likely continued to write what she felt would be successful so she could still have a reason to get out of bed in the morning and work.

Conclusion

Corra Harris is remembered by the people of Bartow County as a stern woman; however, she carried kindness in her heart for her family and the people of her town. She was a product of her upbringing and her life experiences (which significantly differed from how she grew up). While Harris may have preached about the Cult of Domesticity in her writing, the letters and legal documents prove that certainly was not the way she chose to live her life. As her ideals changed, the letters and the biographical information suggest Harris stuck to what she knew would continue to bring her success, so she could continue to provide for her family and the people around her.

Corra Harris did not start any literary movement with her writings. Her works are a reflection of a time that has long since passed and as such have fallen into the obscurity of time. However, her life represents a time of changing ideologies, a time when women began to realize that they could create their own independence, that their role in society could extend past being a wife or housekeeper, and that they could become whatever they were inspired to be.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Terry Powis, KSU faculty, for supervising and assisting me throughout every step of this project.

A special thank you to Mr. Morgan Akin, local attorney and descendant of attorney Paul Akin for sharing these unknown and personal Corra Harris letters and legal documents.

A special thanks to Mr. Joe Head and the Etowah Valley Historical Society for giving me access, guidance and a platform to examine these rare letters and legal documents under controlled conditions including a network of information and people that benefited my research.

I would also like to thank Mr. Head for assisting in reading, transcription and assisting with my analysis of the letters and legal documents. I appreciate the dedication of his time and his knowledge of Bartow County and Corra Harris. None of this research could have been done without the help of these people and KSU students of the 2010-2012 field schools.

Additionally, I wish to specifically thank Mrs. Mary Helen Raines Collier for her interview, interpretive remarks and personal family records regarding her father’s connection to Corra Harris that added valuable insight to the research of this project.

References

Badura, Catherine

2000 Reluctant Suffragist, Unwitting Feminist: The Ambivalent Political Voice of Corra Harris, September 2000 28(3): 397-426.

Coffing, Karen

1995 Corra Harris and the Saturday Evening Post: Southern Domesticity Conveyed to a National Audience, 1900-1930. The Georgia Historical Quarterly 79(2): 367-393.

Edwards, C. H.

1963 The Early Literary Criticism of Corra Harris. The Georgia Review 17(4): 449-455.

Greer, Georgianna H.

- American Stoneware: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters. Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Company.

Harris, Corra

1899 A Southern Woman’s View. Independent 54(1).

Harris, Corra

1914 Mrs. Harris Off to Farm. Evening Post.

Headstamps. N.D. “U.M.C. Co. Headstamp” Last Modified 8-16-16

http://www.headstamps.x10.mx/umcco.html

Oglesby, Catherine

- Corra Harris and the Divided Mind of the New South. Florida: The University Press of Florida.

Talmadge, John E.

1964 Corra Harris Goes to War. The Georgia Review 18(2): 150-156

Tate, Williams

1951 A Neighbor’s Recollections of Corra Harris. The Georgia Review 5(1): 22-23.

Etowah Valley Historical Society (EVHS)

1911-1925 Corra Harris Personal Letters and Legal Documents. Office of the Etowah Valley Historical Society.