The Civil War in Bartow County

The Battle of Allatoona Pass

By: Joe Head

(A Civil War Sesquicentennial Article Series by the Etowah Valley Historical Society in cooperation with the Bartow History Museum)

Bartow experienced a scattered patchwork of guerrilla raids, skirmishes, retaliations and rear guard actions between May and November of 1864. According to Thomas Spencer in a August 28, 1958, Tribune article some 36 war actions were recorded in Bartow during this period.

However, two significant clashes occurred in Bartow, one north of Adairsville at the Octagon House in May and the second south of Cartersville in the Allatoona Community during October, 1864. Both would by most measures qualify as fierce engagements above the classification of a skirmish. Without question, each battle was costly in hundreds of lost lives, additional wounded and missing. However, the Battle at Allatoona was without question the bloodiest action in Bartow County suffering over 1500 casualties between both sides.

It is unfortunate that this battle has not received the respect it deserves when compared to similar conflicts regarding number of troops, casualties and outcomes. Without the support of local history buffs and the Etowah Valley Historical Society, Allatoona would have slipped further into obscurity. Just recently the Corp of Engineers Department of Natural Resources and Friends of Allatoona stepped up to provide recognition for the site as a park. It has only been viewed in official military records and personal letters between officers and soldiers who fought there as a matter of dispute and some confusion as to what really happened. In the end it has been regarded as a small affair between the blue and gray for control of the railroad that yielded little for the Confederates, but preserved the supply line for Sherman.

The Battle of Allatoona occurred October 5th, 1864 following the fall of Atlanta. Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, replaced General Joseph Johnston as commander of the Army of Tennessee and put General John B. Hood in charge. Johnston had long been criticized about his flanking and retreating tactics that repeatedly failed to stop Sherman’s movement.

Hood on the other hand was seen as a more capable battlefield commander, but occasionally reckless and hasty with his daring. However, he was also regarded as a brilliant division commander, but he became less effective as he was promoted.

Davis’ speech was made in Macon, Georgia and was very unflattering to General Johnston. In the end, President Davis’ speech was perhaps responsible for disclosing strategic military tactics to counter Union advancements. His zeal to renew southern hope may have inadvertently revealed Confederate plans to disrupt Sherman’s railroad supply lines north of Atlanta. As Sherman was made aware of the speech, it gave him ample opportunity to reinforce Allatoona with troops from Rome. Sherman was familiar with the Allatoona region from a previous visit in his early career and was not about to underestimate the resources needed to defend the region.

Once named commander of the Army of the Tennessee, Hood’s strategy was to try and lure the Federals away from Atlanta and back north into Tennessee. His efforts were not convincing and he, like Johnston, continued the practice of attacking Federal positions along the railroads.

Hood ordered Major General Samuel French depart Big Shanty (Kennesaw) and proceed north to Allatoona Pass. His instructions were to take the pass at Allatoona and fill the deep cut with logs, brush, rails and dirt. A second order was received to also reach the Etowah River Bridge and destroy it as well. Both orders were lengthy and somewhat inconsistent regarding the main objective. The expectation to accomplish the scope of operation with the number of men and time prescribed was out of balance. It was also noted later that there was no mention that the Allatoona Station had been reinforced with Federal troops prepared to defend the cut. The task to burn the Etowah Bridge never took place.

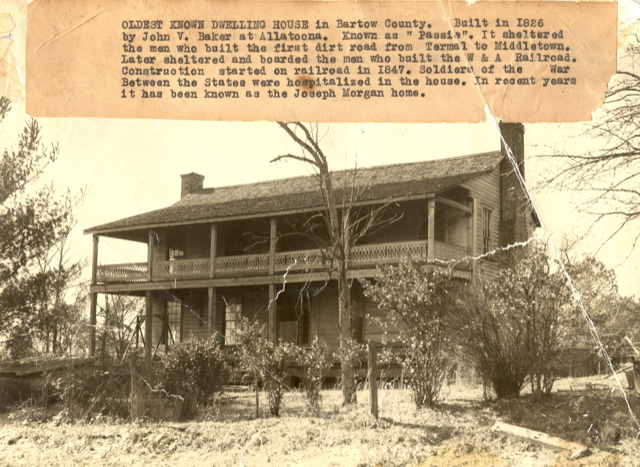

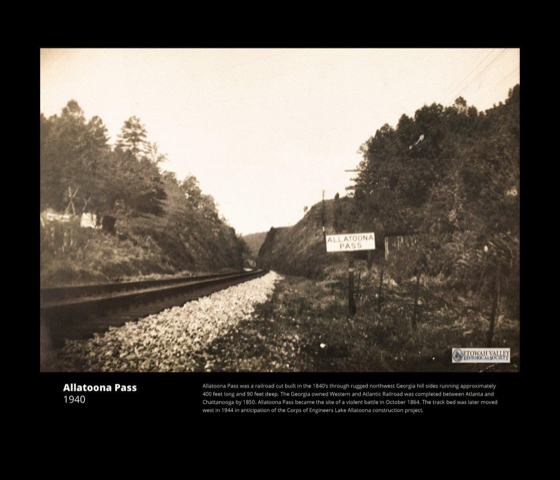

The terrain at Allatoona is a rugged mountain landscape and the deep railroad cut through the pass is 60 feet wide, 175 feet deep and 360 feet in length. It was constructed as part of the Western and Atlantic Railroad project in the 1840’s. Since then the track has been moved to its current location west of Allatoona along side US highway 41 in preparation for the lake construction in 1950.

Upon arrival of the Confederate troops, Lieutenant George Warren, CSA, 3rd Missouri Infantry (Diary, p109) wrote, “As I looked across the intervening space to the bristling forts and viewed the rugged mountain side that lay between, and then cast my eyes along our slender line, I thought to myself there will be hot work if those regiments (Union) are made up of resolute men.”

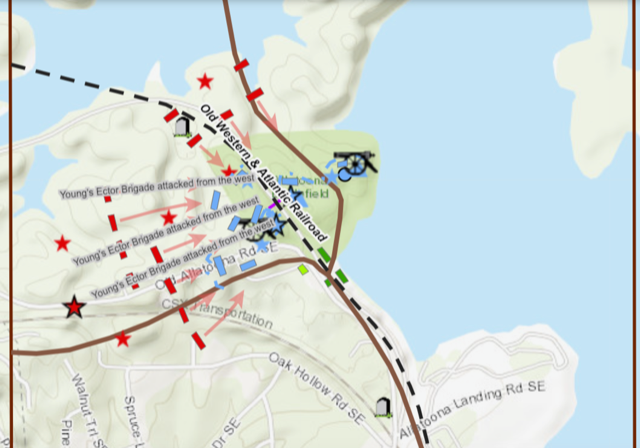

The Confederate forces were under the command of Major General Samuel French, Brigadier Generals Claudius Sears, Francis M. Crockrell and William H. Young. The Union forces were commanded by Brigadier General John M. Corse and Colonel John E. Tourtellotte.

General French sent what has become a famously written demand for surrender to General Corse. His communiqué demanded for Union forces to surrender to avoid a “needless effusion of blood. ” Union commander Corse later replied that they were prepared for the “needless effusion of blood whenever it is agreeable with you.”

The battle commenced at dawn following a two-hour Confederate cannon shelling. Confederate forces out numbered Union forces 3 to 2, however, they were at a disadvantage as the 7th Illinois Infantry Regiment was equipped with the new 16 shot Henry repeating rifles. These were state-of-the-art weapons that were the predecessors of the famous Winchester rifles. The small rail village of Allatoona soon became a war zone involving 5200 men. The depot housed over a million bread rations unknown to the Confederates and the Clayton-Mooney house (still standing today) was used as a hospital.

Union forces had constructed two earthwork defensive positions on high ground, one on each side of the cut. The western position was known as the “Star Fort” (Five pointed star shaped fortification) and the eastern position was called “Rowetts’s Redoubt” (Circled wall fortification with cannon ports). A rope footbridge with wooden slats had been strung across the cut to allow for quick passage.

The Union signal corps had established a signal platform called the “Crow’s Nest” atop of a tall Georgia pine using flags and telescopes. This signal station played a major role in communications that eventually misled the Confederates in believing that reinforcements were in route from Kennesaw. As the battle raged it was reported that Sherman sent a message back to “Hold the Fort” he was coming. This wording is somewhat in question, but the message inspired a gospel hymn written by evangelist Phillip Bliss.

The battle became fierce resulting in hand-to-hand combat. Bayonets, swords, knives, rocks and muskets were used to club opponents. The Confederates were forced to withdraw when news of possible Union reinforcements was learned.

According to an excerpt in General French’s book, Two Wars, both Cockrell and Sears protested and said their men were mad, and wanted to remain and capture the place. Colonel Gates of the Missouri Brigade, declared, that he could capture the fort (Corse’s) in 20 minutes once they were resupplied with ammunition. French stood by his command to withdraw and not risk being trapped by Sherman’s arrival. By 3:00pm it was done and the retreat was well underway.

The wounded were abandoned and the Confederates retreated toward New Hope Church in Paulding County. The dead and injured on both sides were everywhere among trenches, ravines, trees and gulches. It was reported that the dead were being found for weeks afterwards and buried in the locations found.

In comparison, this battle ranks among the bloodiest when compared to the length of the battle’s approximate 6-8 hours and casualties incurred.

The Etowah Valley Historical Society and the Core of Engineers have come to pay tribute to this field of honor by establishing the site as a park and annual event.

_____________________________

References:

The author wishes to express a sincere appreciation to Mr. David Archer for advice and use of his personal research materials to make this article project a reality. Also, a special thank you to J. B. Tate for his reviews and notes. Among other references the author wishes to acknowledge a number of works used in researching the article series including: Lucy Cuynus’ History of Bartow County Georgia, Official War Records, William R. Scaffe’s Allatoona Pass: A Needless Effusion of Blood, Frances Thomas Howard’s, In and Out of the Lines , Papers/letters from the Bartow History Museum, Joseph B. Mahan, Jr., A History of Old Cassville 1833-1864, Dr. Keith Hebert’s dissertation, “CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION ERA CASS/BARTOW COUNTY, GEORGIA” and Joe F. Head’s, The General – The Great Locomotive Dispute.

Joe F. Head

VP Etowah Valley Historical Society