The Material Wealth of Slaves in the South

An Excavation of a Former Slave Cabin Uncovers a Piece of Bartow County’s History

India Daniel

Kennesaw State University

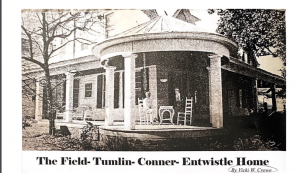

In today’s world, we are curiously reaching back into the past more than ever, in search of not only our country’s history, but also our local history. Through an archaeological field study of a Civil War era home in Cartersville, Georgia, tangible artifacts are now able to help shed a light on past events, particularly as it relates to slavery and the relationship between an enslaved laborer and their enslaver. The Field-Conner home, located in the city limits of Cartersville, still stands today as an important historical site that details the events that occurred during the Civil War, and the personal lives of the enslaved laborers and the family who enslaved them.

Introduction

The enslavement of Africans throughout the world has a rich history. The earliest evidence of them being traded for labor in other countries began nearly four hundred years ago, in the 15th century, during what was known as the transatlantic slave trade. The Portuguese initiated this in 1441, when they captured twelve Africans from modern-day Mauritania and brought them to Portugal (Karbo and Murithi, 2017, 38). Since then, the “need” for Africans to provide labor in other continents, Europe, and eventually the New World, continued to rise.

The transportation of Africans to the Americas began as early as 1503. During this time, enslaved Africans were brought to Europe first, and then to the Americas. By 1518, the captives were taken directly to America from Africa (Adi, 2012). However, before the Americas were actually colonized by Europeans, there was a strong presence of Africans, both enslaved and freed, in the New World. It is speculated that Christopher Columbus brought the first group of Africans to the Americas on his voyage to Hispaniola in the 1490s. Regarding North America, there were a significant amount of enslaved Africans that were brought in 1526, many of whom were a part of the Spanish mission, whose goal was to establish an outpost in present-day South Carolina. This particular group of enslaved people rebelled, preventing them from doing so. However, the Spanish continued to capture Africans, bringing them to St. Augustine in Florida, where there was a great population of enslaved people. Another documented instance of enslaved African being brought to the New World before colonization, or in colonization efforts, include Sir Francis Drake’s voyage in 1586 to Roanoke Island where he and John Hawkins brought as many as 1,400 captured Africans with them, and ultimately failed to establish a colony there (Ponti, 2019).

After many unsuccessful attempts, since the late 15th century, to make a permanent colony in North America by the French, the Spanish, and the English, it finally happened in the 17th century. In 1607, the English founded the first colony in Jamestown, Virginia. As aforementioned, there were Africans, both enslaved and freed, in America before colonization. With that said, it is likely that they were still there, in some form or fashion, even though the “official” year that slavery was incepted in North America was August of 1619. Taken from Angola, the original intent of the Portuguese was to bring the African captives to Veracruz, Mexico. However, the slave ship, San Juan Bautista, was attacked by the Treasurer and the White Lion ships, taking about sixty of their captives. They did this in an effort to encourage the English colonists to transport servants for their labor. From this point, the White Lion arrived at Point Comfort in Virginia, bringing about “twenty and odd Negroes” with them, as John Rolfe, secretary of Virginia, noted, who were then sold to the English colonists in exchange for food. A few days later, the Treasurer ship arrived, selling about three more Africans in Virginia and the rest elsewhere (McCartney, 2011). It is important to note that these African captives were not intended to be “slaves” necessarily. They were sold to the colonists, as were white immigrants from Europe, as indentured servants. Indentured servitude was a contract agreed upon by both the server and the served. The contract was not meant to last forever, meaning that many servants would have the opportunity to become free once they paid their debt, or once their contract was up. Unfortunately, this was the narrative of the European servants, and not of the African servants, who were made to continue working even after their contract was up (History.com Editors, 2019). With the constant influx of enslaved people being brought in primarily from Angola and other African countries, the enslaved African population grew from thirty-two people as of 1620, to well over one hundred people towards the end of the decade (McCartney, 2011); and in 1636, North America’s first direct participation in the transatlantic slave trade began, with the construction of their ship Desire. With the increase in the number of black bodies made to carry out labor against their will in a foreign land, also came the increasingly harsh punishments and treatment towards them, in the name of the law. The first action taken in a lawful manner that showed the racial discrepancy of humans of the same status (indentured servants) took place in 1640, when three men (one black, two white) decided to run away. In the court ruling, the two white men had their years of servitude extended, while the black man, John Punch, was sentenced to be enslaved for the rest of his life. Since then, the literature of laws grew; fugitive slave laws were established, slavery was made legal, enslaved people and indentured servants had to be converted to Christians, hereditary slavery was established, blacks (freed and enslaved) were prohibited from congregating in large numbers and bearing arms, anti-miscegenation laws were established, and slave codes were established, amongst many other laws and rules aimed at restricting and controlling African people as a whole, all before the closing of the 17th century (Lewis, 2019).

Eventually, the original thirteen colonies were formed, with Georgia being the last to do so in 1732. Founded by James Oglethorpe, with the original intent to be a refuge center for prisoners who were in debt in London, Georgia instead came about as a buffer to protect Southern Colonies from Spanish invaders in Florida (History.com, 2018).

Georgia was unique among the other colonies in that its Trustees governed the colony remotely in London and they prohibited slavery. While it was practically becoming illegal in all of the colonies that had been established thus far, in 1693, enslaved people who were able to escape were allowed to live freely in Florida, provided that they converted to Catholicism. This order was from King Charles II of Spain, who allowed this for the purpose of strengthening the number of people in Florida, with the ultimate goal of being able to counter English forces. In 1752, St. Augustine, Florida became the only legal town that a black person could live freely in (Greenspan, 2018). Because of this, in addition to Oglethorpe and the Trustees having a different economic vision for Georgia, slavery was not allowed. Having slavery in Georgia, the buffer of protection from the Spanish, would mean that the very reason Georgia was founded would be compromised. Enslaved people would be enticed to escape to Florida, where they would join the Spanish army and fight against the English colonists in exchange for their freedom. So, unlike the other twelve colonies that yielded a great amount of wealth largely due to their exploitation of black labor, settlers in Georgia were to expect less wealth, with the promise of comfortable living and self-directed labor by manufacturing silk and other commodities.

However, not having other people perform the settlers’ own laborious tasks did not sit well with many of them. Legislation officially prohibiting slavery was passed in 1735. During the latter of the 1730s, settlers grew more and more weary of having to abide by the law. Soon, a campaign was underway to get the Trustees to lift the ban on slavery. They sent letters and petitions, and one of the leaders even went to London to lobby members of Parliament. He tried to persuade them on a financial basis, essentially stating that Georgia could be generating a lot more wealth with the aid of enslaved African labor, because they could withstand the harsh conditions of the south, as their South Carolinian counterparts informed them. However, because of the persistent threat that the Spanish caused for the Southern colonists, Parliament was not interested in their claims. It was not until Oglethorpe defeated the Spanish in 1742, that the Trustees no longer had a plausible reason for keeping Georgia an enslavement-free colony.

As of 1751, slavery was made legal in Georgia, under the provision that there was a smaller ratio of blacks to whites. With this new legislation, the colonists in South Carolina, as they had planned before the ban was lifted, quickly and eagerly expanded their plantations, bringing themselves and the enslaved to the Georgia Lowcountry. South Carolinians soon took over Georgia’s government, implementing some of their own governing laws and socioeconomic practices, including a set of slave codes. Subsequently, they ended up taking over a significant amount of the Georgia colony, where their wealth outweighed the wealth of the original colonists. Eventually, the enslaved population grew from about 500 to about 18,000 by 1775. This drastic increase is largely due to the presence of the colonists of South Carolina, and due to the fact that Georgia began to import enslaved people directly from Africa in the 1760s (Wood, 2019).

These events set the stage for a scene that delves into the specific lives of Africans brought to the New World. Because the history of slavery has many different aspects, and because it can be so extensive, a detailed description of life for any one enslaved person (who is not a historical figure) is often overlooked and forgotten. This is especially the case for the enslaved people of the Field-Conner home in Cartersville, Georgia. While there is not much literature on the house and its inhabitants, the archaeological field work on the former plantation indicates that there is a need to tell the story of those who lived there, in particular, the enslaved people at this site, who seemingly had access to items that were not typical for an enslaved person to possess. That raises the question of why they did have access to these things. Perhaps the enslaved people here had a special relationship with their enslavers, possibly indicating that slavery in the south was not “as harsh” in all areas. Another possibility is that the family of the Field home were wealthier than a typical slave owning family, meaning that the enslaved people, presumably, in turn, would have better things as well. Through an extensive analysis of the artifacts that were found at this location, the distinction of the enslaved population living here will be explored.

Slavery in the South vs Slavery in the North

It is a well-known fact that slavery in America greatly differed in the southern part of the country compared to the northern part of the country. Even in its beginning stages, the thirteen colonies had different economies, policies, and social order based on their respective regions. It is important to note that the reason that these thirteen colonies came into fruition in the first place was due to a demand in England. In the midst of European powers wanting to expand their territories, and with England’s increasingly overcrowded population, and their own economy suffering, they sent people (those looking for work, a fresh start, and religious freedom, alike) to North America with the primary means of them creating a new economy to bring in more revenue and build the country’s wealth. The colonies did that in different ways, while all relying on the labor of enslaved Africans.

In what is referred to as the New England Colonies, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut, were the northernmost colonies. Because their geography did not allow for large plantations, they did not have as large of a demand for enslaved labor as their southern counterparts. Southern Colonies needed more enslaved Africans because their economy was agriculturally based, rather than having an economy based on manufacturing goods, as New Colonies did. The average enslaved population belonging to one house/farm was about one to two people. Because of the lack in numbers and a different variety of economic needs, enslaved people here had the opportunity to become more specialized in certain crafts.

Enslaved people living in the New England Colonies were arguably treated better than those in the Middle and Southern Colonies. For one, they did not have to experience tremendous heat conditions, while also having to be outside for an extended amount of time – sunrise to sunset. Most of their duties, outside of farming, involved in-house duties, among other things such as aiding ministers, doctors, and merchants. Enslaved people here were initially treated and regarded as indentured servants, per English custom.

Indentured servitude for African labor ceased in 1641, with the Massachusetts Bay Company imposing slave laws that differentiated the treatment of a servant and an enslaved person. Doing this took away any of their former rights, such as eventually obtaining freedom. Even with the employment of a stricter form of slavery, the New England Colonies still kept a “calmer” climate compared to the other colonies. As early as the 17th century, Rhode Island, with the highest population of enslaved people, tried to implement laws that would give enslaved people and indentured servants some of the same rights. The laws also aimed to free them after ten years of forced service. Even though these laws eventually failed, it still shows that the New England Colonies differed greatly in the northeast compared to the southeast; thus, setting the stage for the “free north” that would come in the years to follow.

The American Revolution played a role in enslaved people obtaining their freedom. Though an enslaved person would be said to have freedom for joining the war, whether they were from the north or the south, there was a stronger presence of enslaved people obtaining freedom in the north. Connecticut and Rhode Island, for example, made moves to cut the active slave trade prior to the war. Even later during the American Revolution, New England Colonies began to fully outlaw slavery as early as 1777, and by 1800 there was no slavery in those colonies (National Geographic Society, 2020).

In the Middle Colonies, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Delaware, there was this sort of duality, where enslaved people in these colonies could experience as much hardship in terms of treatment and labor as those in the Southern Colonies, and where they could experience more privileges and freedom as those living in the New England Colonies.

The Middle Colonies also had “the best of both worlds” regarding their economy, which included agricultural and industrial labor. One important difference to note between the Southern and New England Colonies compared to the Middle Colonies, is that their economy was not solely reliant on one particular industry. It is also important to note that the colonists in the Middle Colonies were not only English people. There was also a strong German and Dutch presence, meaning that the colonists living here had different reasons for coming to the New World, and that they had different means of making a living, rather than strictly relying on indentured servitude, and ultimately slavery, as the other colonies did.

Immigrants moving to the Middle Colonies often paid their own way and were not indentured servants looking to pay off debt. In most cases, they were relatively wealthy and skilled in farming and other trades, allowing them to generate their own wealth. However, because there was a halt in the flow of immigrants coming to these colonies, there was a need to bring in more enslaved Africans. Even with its inception, the difference in these colonies compared to the others, is that the white settlers worked alongside the enslaved for particular labor tasks.

Because of their geography, land with plenty of fertile soil and space, colonists’ desire to own land grew, lessening the number of white workers, and increasing the number of African captives. The Middle colonists imported most of their enslaved people from the West Indies, rather than directly from Africa, because they were more “broken in” and accustomed to life in the New World. The enslaved people living in the Middle Colonies worked on plantations just as those in the south, but their cash crops included wheat, barley and corn, among other things – making them the “breadbasket colonies.” This type of agriculture called for short growing seasons and harvesting seasons. Because of this, in addition to there being a relatively small population of enslaved people per household/farm, as in the New England Colonies, enslaved people had more idle time. However, they were not limited to working on plantations. They would also engage in artisan work, such as carpeting, blacksmithing, and shoe making, to name a few.

In terms of life for enslaved people, the Middle Colonies soon adopted a set of slave codes in the early 1700s, giving their enslavers the right to essentially do whatever they wanted with them. Because there was a small slaveholding, enslaved people in the Middle Colonies had less of an opportunity, and more of a hard time, trying to organize a revolt or rebel against their enslavers. There were some successful attempts, but generally it was difficult for Middle Colony Africans to effectively communicate and organize with each other.

Eventually, the enslaved population continued to grow in the Middle Colonies. With ports in cities in states such as Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, the Middle Colonies played an active role in the transatlantic slave trade. Though slavery was thriving in these colonies, there were still colonists who opposed it and worked against it, such as Quakers, who would be known to help runaway slaves. There were also others, such as New Jersey’s governor, William Livingston, who opposed slavery, stating in 1786, that it was “utterly inconsistent both with the principles of Christianity and Humanity; and in Americans who have almost idolized liberty, peculiarly odious and disgraceful.” (Gigantino, 2020). The first move made to amend the institution of slavery was in Pennsylvania in 1780, where freedom would be granted to a child born into slavery once they reached the age of twenty-eight. By 1840, slavery was completely abolished in Pennsylvania. They were mainly successful in doing this because their economy was not mainly reliant on slavery. For colonies like Delaware, however, totally abolishing slavery was not the answer. Slavery in the Middle Colonies officially ended with the 13th amendment in 1865, when New Jersey finally had to fully abolish it. However, the presence of slavery greatly declined in these colonies before 1865 (Gigantino, 2020).

Slavery in the Southern Colonies differed greatly in different aspects when compared to the New England Colonies and the Middle Colonies. It is often regarded as the harshest, due to many factors such as the climate, with its intense heat, laws permitting inhumane treatment towards enslaved people, the laborious work they had to carry out, and the longevity of it since its beginnings.

The Southern Colonies, including Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, faced different hardships compared to the other regions. For example, many northern immigrants from Europe came to North America for religious freedoms, meaning that they often came with their families. This was not the case for Southern colonists, who would generally be without their families, working as indentured servants and/or seeking economic opportunity. In addition to this, they also had to adapt to the new climate in the south, which caused many of them to contract diseases such as malaria and yellow fever, shortening their life expectancy. Because of all of this, life for Southern colonists had a rough start, and was not as promising as life was in the other colonies (Ushistory.org, 2020). However, things would quickly change in the colonists’ favor once slavery began to increase.

In Virginia, the first colony founded, their economy was agriculturally tobacco based. Enslaved people would work on tobacco plantations, expanding the economy. Due to its high success, the time, labor, and amount of land that was needed increased, in order to continue producing this cash crop, which was sold in England. Their soil eventually lost its nutrients because of their extensive use of the land, causing the colonists to have to barter most of their goods. This established a new way of obtaining goods, where people would trade tobacco for service and other commodities such as food.

Regarding their political structure, Virginia had what was known as the General Assembly. Established on July 30, 1619, it was the first elected legislative body in the New World. The General Assembly also created laws for the relationship between an enslaved black person and their enslaver, stating “All servants imported and brought into the Country…who were not Christians in their native Country…shall be accounted and be slaves. All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion…shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resist his master…correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction…the master shall be free of all punishment…as if such accident never happened. (Pbs.org).” The life of an enslaved person in Virginia, outside of planting tobacco, consisted of working as blacksmiths, carpenters, among other similar jobs. Those who did not work on the plantations tending to the crops, worked inside as maids, cooks, and nannies. During their own personal time, they would tend to their personal duties and garden. In the beginning, they were also sometimes allowed to raise their own food and tobacco, with the option of selling some of their goods to make a profit. They would also engage in dancing and singing, continuing some of their African traditions (Historyisfun.org).

This is what the beginnings of slavery looked like in the south. However, well after 1619, there were major changes that took place in this new economic system. The South allowed for year-round growing and harvesting seasons of cash crops like rice, indigo, tobacco, sugarcane and cotton. This, in addition to large plantations, required the labor of a lot more enslaved people than the other colonies did. This is why the enslaved population was so great in this region. Setting them further apart from their fellow colonies, Southern Colonies were largely self-sufficient. This meant that any family, especially the wealthier families, could rely on the efforts of their own labor and their slaves’ labor, producing whatever they needed. This type of self-sufficiency did not require them to have a lot of cities as seen in the Northern Colonies.

As slavery grew, so did enslaved people’s resistance. Consistent with enslaved people living in other regions, they would move slowly, delaying their work, and pretend to not understand tasks that they were given. With a larger population and about twenty to thirty enslaved people working on one plantation, it was easier for them to communicate and organize, something that was less plausible in the other colonies. With these organized attacks and rebellions, came the enforcement of stricter laws and harsher punishments, not only for runaway or rebellious enslaved people, but for all of them. The enslaved people living in the south faced stricter laws than those in the northern colonies, prohibiting them from marrying, from gathering without the presence of a white person, and there were seldom any chances for them to earn their freedom. In South Carolina, for example, they could not even plant corn, peas, or rice, have hogs or cattle, and they could not wear clothing that was “finer than negroe cloth” (Lumen). Southern enslaved people lacked such privileges compared to northern enslaved people because of their population size. It would be easier for one to two enslaved people to build a personal relationship with his/her enslaver and establish a patriotic bond, thus increasing his/her chance of receiving certain benefits, compared to twenty or more enslaved people living in the south trying to receive “mercy” from their masters.

Even with the decline in tobacco in Virginia and Maryland, the Southern Colonies remained relevant and functioning, as they continued to cultivate their other cash crops. A staple cash crop, cotton, took over the south’s economy, making enslaved Africans more of a commodity. With this increasing reliance on enslaved labor to continue to be the foundation of the south’s economy, the Southern Colonies were more reluctant than ever to abolish slavery or appeal some of their inhumane policies towards the enslaved people, as the northern colonies pushed them to do. It wouldn’t be until 1865, with the ratification of the 13th Amendment, that slavery came to an end in all southern states, lasting much longer than the other original colonies.

Slavery in South Georgia and North Georgia

By 1810, Georgia had a population of 105,218 enslaved people, increasing to 280,944 by 1840. At the beginning of the Civil War Era, there were more enslaved Africans in Georgia than any of the southern states, excluding Virginia. Georgia, becoming the face for slavery in the south, also had the highest number of large plantations in the south (Young, 2017).

Lowcountry Georgia, an area along the southeastern coast, included Savannah – where the cotton gin was created – and territories in South Carolina. In the Lowcountry, there were about 30,000 Georgian enslaved people. Most of their work included cultivating rice, which was a dangerous and strenuous task. For example, between the years 1833 and 1861, there was a ten percent mortality rate each year on one rice plantation. There would also be cholera outbreaks, causing death for about half of the enslaved population. Infant mortality rates were also significantly higher in the Lowcountry, compared to infants, both black and white, elsewhere. In general, enslaved people here were faced with a lot more health challenges and complications than those living in other areas (Young, 2017).

One benefit of enslaved people living in Lowcountry Georgia, is that they had a greater degree of autonomy in terms of their social life. This was because whites did not want to be in the disease ridden, humid environment that the Lowcountry was known for, particularly on the rice plantations. In turn, enslaved people were allowed to leave the fields once their work was completed. With a lack of supervision and white culture influence, a different type of lifestyle transpired for them. For one, they were able to retain more of their African heritage, practicing the language, dances, religion, and other cultural traditions, hence the Geechee culture still present along the coast today. The enslaved people here were also able to create opportunities for themselves, becoming businessmen, creating markets for both white and black consumers. Outside of working on the rice plantations and selling their goods/services, slaves would sometimes be hired out to do work that they were skilled in.

Enslaved people living elsewhere in Georgia had somewhat of a different reality. The Black Belt, referring to the rich, fertile soil in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Georgia, is where most of the state’s population lived. Three-fourths of Georgia’s enslaved people lived in the middle counties on cotton plantations, and two-thirds of the entire population also lived here. The enslaved, in turn, were watched and supervised more intensely than those living in Lowcountry Georgia, while also having less control over their own lives and free time.

Outside of the enslaved people in Lowcountry Georgia, compared to the rest of the enslaved population, there was relatively little difference between those living in the northern and southern regions of Georgia. There were not a lot of slave-owning people in Georgia, even though the impact of slavery does not suggest that. As of 1860, less than one-third of white males enslaved blacks, making enslavers the minority in Georgia. Only about fifteen percent of enslavers had twenty or more enslaved people and about forty-eight percent of enslavers had less than six slaves. Georgia’s plantation economy was divided in a way that put the fifteen percent of enslavers of twenty or more enslaved people at the top – they were the elites, who also made up the majority of the government, and had control and access to the best land options (Young, 2017). While there was a smaller presence of enslaved people in North Georgia, the treatment and/or benefit, or lack thereof, of any enslaved person was largely based on the personality or morals of their enslavers. This means that enslaved people living in the same area could be treated completely opposite of each other, even though they are in the same geographic area, and vice versa.

Slavery in Cartersville, Georgia

The history of slavery in Bartow County, as in many small towns, is a history that has many untold parts. In what was formerly known as Cass county, slavery was practiced in this north Georgia county before it was established in 1832. Enslaved African labor in North Georgia was not as concerned with cotton as the Black Beltline region was. With a smaller and more stable population of enslaved people, they typically labored in mining and industrial work. As their population grew with the introduction of the Western and Atlantic Railroad, running from Chattanooga to Atlanta, the county was positively impacted economically, politically, and socially. Farmers living here were now able to increase their access and participation in the cotton industry in the 1850s. Soon, the population became increasingly educated, wealthy, and more viable in exploiting black labor (Claremont, 2005, 8-9).

As a testament to the influx of enslaved people in Cartersville and to the wealth that could be generated, there were several well to do slave owners. Two of the most notable slave owners there included Colonel Francis S. Bartow and Colonel Farish Carter. Bartow, whom Bartow County is named after, was a prominent member of the Georgia bar. He had a total of eighty-nine slaves by 1860 (Groce, 2008). Farish Carter, whom Cartersville is named after, was one of the wealthiest men in Georgia during this time period. As of 1845, Carter owned 426 slaves (University Libraries). However, he did not solely rely on his wealth from what his enslaved laborers could do for him; instead, he would loan them to others, including family and friends, having them carry out work for different construction projects (Daniels, 1999).

The Field-Conner house, located at 118 North Erwin Street, is regarded as the first house built in Cartersville, where they also employed the use of black labor (Figures 1 and 2). Understanding the history of this house and its inhabitants is important, because this research is based off of the artifacts that were found at this site in one of the slave cabins and the surrounding areas. Per documents from Bartow’s county local historian, Alexis Carter-Callahan, the house was speculated to have been built around 1855. Elijah Murphy Field of Canton, Georgia, and Cornelia Maxey Harrison of Pickens, South Carolina, married in 1849 in Cass County, and proceeded to move into the home in 1858. In 1864, as the Union Troops approached Cartersville, Field uprooted his family and moved to Bethany, now Wadley, Georgia. Field died later that same year, and Mrs. Field moved back to the house with her children in 1865. During the house’s time of in-occupancy, Union soldiers moved in the house, including Mrs. Field’s own cousin, former United States President General Benjamin Harrison, whom she resented because of his “Yankee loyalty.” Ultimately, during the end of the Civil War Era, the house served as quarters for Mrs. Field and her children, Union soldiers, and a post office.

City Map of Conner Home/Vinnie Cabin

Figure 1. Map of the location of the house (Google Maps).

Figure 2. The Field-Conner home (Stompin’ Grounds Magazine, pg. 18).

The Fields also had other properties around Cartersville, including a place between Pumpkinvine Creek and Etowah River, where the majority of their “one hundred or so” enslaved people were. However, there is no record of the number of enslaved people that were actually living on the property in Cartersville. The Field family did have in-house, as well as out-house, enslavement. There are enslaved people’s names recorded here, including “John, who was in charge of the stables, and Anne, who was the cook and the maid.” Henry is also mentioned as the “head of slaves”, but the plantation that he belonged to was not specified, though it is likely that he was at the other site near Pumpkinvine Creek. A source from the Stompin’ Grounds Magazine states that Mr. Field “never actually purchased slaves, rather he inherited them, and they multiplied in number once doing so.” He opposed slavery and did not think that it was right to own humans. However, he never got rid of his, claiming that he did not want to “separate the families.” Once the war was over and they were freed, however, some of the enslaved people would still come by to see the family and check on them. The Stompin’ Grounds Magazine also states that the Fields and the people that they enslaved treated one another like family, and that they took care of each other. This was evidenced in the fact that Henry gathered the rest of the enslaved people and went to Bethany once they heard that Mr. Field passed away, in an effort to console and protect Mrs. Field.

Of particular interest, is the slave cabin, sitting about sixty feet from the main house, that still remains today on the Field’s former property in Cartersville. After the war, as mentioned earlier, some of the newly freed enslaved people still stayed around the area, stopping by the house every now and then. It is likely that some of the enslaved people continued to work there, or at the other property. Mrs. Vinnie Johnson, the head cook and last known occupant of the slave cabin that is still standing, worked for the Field family (Figure 3). She lived in the cabin with her son between 1900 and 1910, eventually earning enough money to move off of the property and rent her own home. Descendants of the Field family continued to occupy the house until it was sold to John Lewis, in 2017.

Figure 3. Mrs. Vinnie’s cabin. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Artifact Analysis

An archaeological survey of the property was conducted through metal detecting, yielding several artifacts. So far, there are over one hundred artifacts that have been catalogued from the Field-Conner home. The majority of those artifacts include fragments of kitchenware (glass, whiteware, etc.), buttons, and square-head nails, among other items. It is speculated that there were at least ten slave cabins on the Field’s property at their town house in Cartersville. This speculation is evidenced through the remaining structures that have also been discovered through metal detecting. Those structures would include brick fragments, square head nails, and window glass. The property would have to undergo further analysis in order to make a solid claim that there are in fact, at least nine other slave cabins in addition to the one that is still intact.

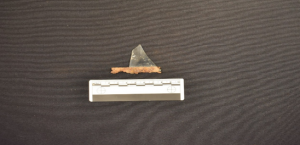

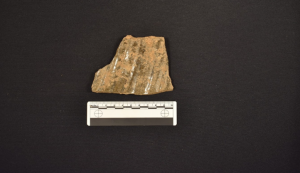

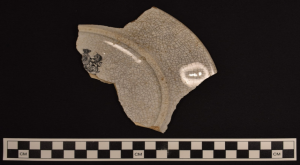

The artifacts that were found have been separated into ten different categories that include architecture, furniture, clothing, kitchenware, activities, personal, arms, modern, tobacco and miscellaneous. Under the architecture category, there were artifacts such as a trunk lock, drawer pulls, bed frame pieces, door hinges, animal bone fragments, bricks, alkaline glazed stone pieces, a window hinge with glass, and possible flowerpot fragments. Of this list, the window hinge, the door hinges, and the flowerpot fragments are the most typical findings at an enslavement site. Depending on the time frame, other findings such as the animal bone fragments and bricks would also be common. The animal bones could be indicative of tools or remains from their meat food source, which would most likely be a pig or a cow (Figure 4). In the beginning stages of slavery, slave cabins would not have wooden floors. Instead, the floor would simply be the earthen ground. Moving out of the 1700s, the structure of slave cabins began to change. Where there was once only an opening as a window with no covering, glass-paned windows began to emerge, as well as brick or stone fireplaces. Evidence of burned brick and coal (Figure 5), and the windowpane with glass (Figure 6), represent these antebellum changes (Samford, 1996, 95-97)

Animal Bone Fragments

Figure 4. Animal bone fragments. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Brick fragments

Figure 5. Brick fragments. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Window Pane

Figure 6. Window pane with glass fragment. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

The alkaline glazed stone pieces would not necessarily be uncommon, as some enslaved people did actually engage in pottery making. In Edgefield, South Carolina, for example, they played a key role in the stoneware industry. The enslaved people there, the most renowned being Dave the Potter, even implemented their own stylization of pottery that suggested influence from their Kongo ancestors, which made up seventy percent of the population of enslaved people during the 18th century (Joseph 2011, 138). While it is uncertain whether the enslaved people living at the Field-Conner home engaged in pottery making, it would not be unlikely. Because all of the stoneware is fragmented, it is difficult to determine whether or not the pottery had African-style features (Figure 7). Regardless, enslaved people did have access to pottery, whether it was passed down from their enslavers, or whether they created it themselves (Sciway.net).

Glazed Stone

Figure 7. Alkaline glazed stone piece. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

The bed frame pieces, the drawer pulls, and the trunk lock help to paint a vision of what the inside of the cabin may have looked like. The trunk lock raises less significance, as it could simply be a storage place for the enslaved people’s tools, which was not uncommon for them to have (Figure 8). It could have also been used by their enslavers. Because nothing else was found in possible association with the trunk lock, it is difficult to draw upon any conclusions as to what could have possibly been inside of the trunk. The bed frame pieces (Figure 9) and the drawer pulls (Figure 10), however, are of great significance, and have more specific implications. There are several accounts where enslaved people would recall their sleeping arrangements and conditions: “Boards fixed upon stakes driven into the ground, without mat or covering, were our only beds.”; “Old and young, male and female, married and single, were glad to drop down like so many brute beasts upon the common clay floor, each covered with his or her own blanket, their only protection from cold and exposure.”; “…old and young, male and female, married and single, drop down side by side, on one common bed – the cold, damp floor – each covering himself or herself with their miserable blankets…”; “We had neither bedsteads, nor furniture of any description. Our beds were collections of straw and old rags, thrown down in the corners and boxed in with boards; a single blanket the only covering. Our favourite way of sleeping, however, was on a plank, our heads raised on an old jacket…” (Simkin, 2020).

Trunk Lock

Figure 8. Trunk lock. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Slotted bed frame latches

Figure 9. Bed frame pieces. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Drawer Pull

Figure 10. Drawer pull. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

All of these personal accounts by former slaves indicate that throughout time, slave cabins were devoid of any furniture, including beds. What is conflicting in the case of this slave cabin, is that it was occupied both during slavery and after slavery. Thus, it is uncertain if the enslaved people’s benign relationship with the Field family granted them the luxury of having beds, or if Mrs. Vinnie, the last known occupant of the cabin post-Civil War, had a bed. However, with further analysis of the site, if more bed-related fixtures are found, particularly in/around the other speculated slave cabins, then it would be safe to conclude that the enslaved people did, in fact, have beds. Also attesting to the presence of furniture in the slave cabin, is a wooden chair leg, catalogued under the furniture group (Figure 11).

Chair Leg

Figure 11. Wooden chair leg. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

In the activities category, items include a horse saddle buckle (Figure 12), a horse branding iron (Figure 13), and a flat iron (Figure 14), and a tobacco canister (Figure 15) listed under the tobacco category; all of which are common. In the clothing category, the artifacts include a buckle (Figure 16), several buttons, pendants, and beads (Figure 17), a child’s shoe made of horsehair (Figure 18), and scissors (Figure 19). All of these items are also common. However, the type of buttons that were found are remarkable. They range in material, from copper, iron, bone, shell, vulcanized rubber, plastic, and porcelain. The copper and iron buttons are mostly Civil War Era pendants from the suits of the soldiers. This, of course, is largely consistent with the presence of the Union Soldiers occupying the house. Under the arms category, items include a trigger guard (Figure 20), and lead shots. These likely belonged to the Union Soldiers as well. However, other enslavement sites yielded similar findings such as lead shots, gunflints, and other gun parts. Despite popular belief, enslaved people did have access to firearms, which they mainly used as a means for hunting (Samford, 1996, 96). Another weapon that was found was a pocketknife, under the personal group (Figure 21). Again, all of these items were more than likely from the Union soldiers, but enslaved people in general could have had possession of them as well.

Saddle buckle

Figure 12. Horse saddle buckle. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Branding iron

Figure 13. Horse branding iron. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Flat iron base

Figure 14. Flat iron. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Figure 15. Tobacco canister. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Clothing buckle

Figure 16. A clothing buckle. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Buttons and Beads

Figure 17. A pendant, beads, and several buttons. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Child’s shoe sole

Figure 18. Children’s horsehair shoe. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Figure 19. A pair of scissors. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Gun trigger guard

Figure 20. A trigger guard. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Pocket knife blade

Figure 21. A pocket knife. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

The kitchen category had the most artifacts, mainly because of the many small fragments that were found. The artifacts were mainly whiteware pieces and glass pieces. Because of the nature of the slave cabin, it is difficult to determine what exactly these artifacts indicated for the enslaved people that lived here. In general terms, enslaved people did not have dishware, outside of the pottery that they could make themselves, as mentioned earlier. The dishware that was found here was relatively prestigious, being English tableware and of fine material (e.g. porcelain). Fragments of some of the dishware included makers marks, which were all of English origin, dating as early as the 1840s through the ending of the Civil War (Figures 22, 23, 24, and 25). A typical enslaved person certainly would not have had access to such fine ware. However, because Mrs. Vinnie was the head cook, it makes sense that there would be such kitchen-related items found. Additionally, there was an outside kitchen that was torn down, which could have been the area in which most of the kitchen artifacts were found.

Figure 22. Englishware. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Figure 23. Englishware. Photo courtesy of India Daniel.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the enslaved people living here, did in fact have benefits that were unusual for a typical enslaved people living in the south. Slavery in the South, particularly Georgia, is characterized by its brutal heat, extensive and intensive labor regime, and relentless enslavers. While this can still attest to the general nature of slavery, it is important to note that this was not the reality on every single plantation. To be clear, the act of slavery in America is not excusable or tolerable on any level. However, because of the nature of thinking during its time, people, such as the Field family, who sought to create a different, “more favorable” environment for the people the enslaved, were regarded as good people, who meant no harm. The family treated them like family, meaning that they were granted with certain privileges that were unknown to other enslaved people elsewhere. Such conclusions can be made thanks to documents that explicitly state the relationship that the Field family had with those who were enslaved.

In terms of making conclusions based on the artifacts, things are a bit more difficult. The Field-Conner home has a unique history, involving unique situations. As stated previously, the home has been occupied for over the span of a century, during and after slavery. Because of this, it is difficult to determine what would have belonged to who.

The house was abandoned for the period of time that the Field family moved to Bethany, Georgia. Upon Mrs. Field’s return to the home, it was occupied by Union soldiers. It is not out of line to think that others could have occupied the home for a brief time before the soldiers. Even if that is not the case, it is still important to consider the nature of the enslaved people and what they were doing while their enslavers were not present. It is said that Mrs. Field ordered the “head slave”, Henry, to continue to plant the crops as if she was there to oversee their work, but Henry gathered as many enslaved people as he could, and actually went to Bethany where the family was. Because of their autonomy and free will to be able to do this, it raises many questions. Did some enslaved people use this as an opportunity to run away? Did they use this as an opportunity to take certain items from the house that they would otherwise not have been able to? And, did this journey to Bethany include the enslaved people at the Field-Conner home, since it is likely that Henry was an enslaved person at their other plantation? The only basis that there is to answer these questions relies on what is known about the relationship between the enslaved people and their enslavers. If it was as family-oriented as documents suggest, then perhaps they remained loyal to their enslavers, and did not use their absence as an opportunity for freedom or personal gain. Perhaps in return for their loyalty and concern for their enslavers, the Field family rewarded them with certain belongings, or perhaps these belongings were already granted to them, consistent with the story of Mr. Field caring for them and treating them like family.

Furthering the point of the house having different inhabitants, it is unclear what items would have belonged to Mrs. Vinnie, or what items were in use before her. In the case of the bed frame pieces, for example, many possibilities exist. Perhaps the enslaved people here did have beds, and it was still there by the time she inhabited the cabin with her son. Perhaps Mrs. Vinnie and her son were given furniture or allowed to have it since slavery was no longer legal. Also, they did not move to the property until 1900. This raises the question of whether or not the cabin was empty from 1865 until then. Because the freed enslaved people still stopped by to check on the family, it is possible that some of them still lived on the property or stayed there during that time frame. It is also possible that the slave cabin could have been inhabited by other workers once Mrs. Vinnie and her son left. All of these possibilities add to the uncertainty of the artifacts found.

Additionally, the relationship of the Union soldiers and the enslaved people is unclear. Surely, they served the soldiers, and a superior relationship was established, with the soldiers being the superior, but to what extent? If the enslaved people were, in fact, used to being treated like family, how did that relationship carry over to this added military relationship? Did the soldiers also find a special or familial relationship with the enslaved people, granting them certain belongings? It is interesting that military paraphernalia was found near the slave cabins. Documents state that the troops occupied the lower level of the house, but they could have very well spent time in and around the slave cabins.

Another speculation adding to the material wealth of the enslaved people here, is that the Field family were wealthier than the typical enslaving family. As discussed earlier, Mr. Field inherited enslaved people. While the exact number of enslaved people that he inherited is not documented, it is known that the family had one hundred of them or more. In Georgia, only about 6,000 of the 41,000 enslavers had twenty or more enslaved people. These enslavers, Mr. Field included, were considered the elites of Georgia’s society and economy. Mr. Field came from a wealthy family and generated his own wealth through his company and success as a planter. Mrs. Field also came from a family associated with wealth, as her uncle was the ninth United States President, and her cousin, also the general who occupied the house, was the twenty third United States President. All of these are contributing factors to the family’s wealth, and perhaps to the testament that these enslaved people saw certain benefits from that wealth.

All in all, there can be a number of reasons why the enslaved people living here had belongings that were not typical for them to have. There is not one solid answer to the question of such wealth, but instead a seemingly infinite number of possibilities that could have contributed to it. Regardless, the narrative of the enslaved people living at the Field-Conner home is unique in itself. The rich history of the house and its inhabitants is like no other known in North Georgia. Through studying the deep and intricate history of slavery in America, and elsewhere, it is important to look beyond the generalizations that are made about it, based on geographic location, an area’s economy, and so on. The life of an enslaved person on each plantation could greatly differ across the board, and had features that made it unique, even if compared to a neighboring plantation. The treatment of an enslaved person, the things that they had access to, their punishments, and their rewards were largely dependent on the nature of their enslaver.

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this time to thank John Lewis, the current property owner of the Field-Conner home, for allowing an excavation of the property to take place, and for also allowing me to analyze the artifacts. I would also like to thank Alexis Carter-Callahan, the local historian, for her profound knowledge of the Field-Conner home, and the resources that she extended to me for use in this research. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my professor, Dr. Terry Powis, for his guidance and expertise throughout this research, and for also allowing me to work under his tutelage. Without these individuals, none of this would have been possible.

References

Adi, Hakim. 2012. “Africa and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.” BBC. Last modified October 5,

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/africa_article_01.shtml#top.

Claremont, Alexa I. 2005. “Creators of Community: Cassville, Georgia 1850 – 1880.” Masters

diss., The University of Georgia.

Daniels, Amy. 1999. “Cartersville: The Stories Behind the Name.” Etowah Valley Historical Society 31.

Gigantino, James J. 2020. “Slavery in The Middle States (NJ, NY, PA).” Encyclopedia.com.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/slavery

Middle-states-nj-ny-pa.

Greenspan, Jesse. 2015. “8 Things you May Not Know about St. Augustine, Florida.” History.

Last modified September 1, 2018.

https://www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-st-augustine-florida.

Groce, W. Todd. 2008. “Francis S. Bartow (1816-1861).” Georgia Encyclopedia. Last modified September 9, 2014.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/francis-s-bartow-1816-1861.

History.com Editors. 2019. “First enslaved Africans arrive in Jamestown, setting the stage for

slavery in North America.” History.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-african-slave-ship-arrives-jamestown-colony.

History.com Editors. 2009. “Georgia.” History. Last modified August 21, 2018.

https://www.history.com/topics/us-states/georgia.

Historyisfun.org. n.d. “What was life like for enslaved people on farms in colonial Virginia?”

Jamestown Settlement & American Revolution Museum at Yorktown. Accessed March 15,

2020.

https://www.historyisfun.org/learn/learning-center/what-was-life-like-for-enslaved-people-o

n-farms-in-colonial-virginia/.

Joseph, J. W. 2011. “”… All of Cross”—African Potters, Marks, and Meanings in the Folk Pottery

of the Edgefield District, South Carolina.” Historical Archaeology 45, no. 2 (2011):

134-55. www.jstor.org/stable/23070092.

Karbo, Tony, and Tim Murithi. 2017. The African Union: Autocracy, Diplomacy and

Peacebuilding in Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Lewis, Femi. 2019. “Enslavement Timeline 1619 to 1696.” ThoughtCo.

https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-enslavement-timeline-45398.

Lumen. n.d. “Slavery in the U.S.” Boundless US History. Accessed March 15, 2020.

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/slavery-in-the-u-s/.

McCartney, Martha. 2011. “Virginia’s First Africans.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Last modified

October 8, 2019.

https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/virginia_s_first_africans#start_entry.

National Geographic Society. 2020. “New England Colonies’ Use of Slavery.” National

Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/new-england-colonies-use-slaves/.

Pbs.org. n.d. “Virginia’s Slave Codes.” PBS. Accessed March 15, 2020.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p268.html.

Ponit, Crystal. 2019. “America’s History of Slavery Began Long Before Jamestown.” History.

Last modified August 26, 2019.

https://www.history.com/news/american-slavery-before-jamestown-1619.

Samford, Patricia. 1996. “The Archaeology of African-American Slavery and Material Culture.”

The William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 1 (January): 87-114. doi:10.2307/2946825.

Sciway.net. n.d. “The Lives of African-American Slaves in Carolina During the 18th Century.”

Sciway. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.sciway.net/hist/chicora/slavery18-3.html.

Simkin, John. 1997. “Slave Housing.” Spartacus Educational. Last modified January, 2020.

https://spartacus-educational.com/USAShousing.htm.

University Libraries. “Farish Carter Papers, 1794-1868.” Accessed July 28, 2020.

https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/02230/.

Ushistory.org. 2020. “The Southern Colonies.” US History. https://www.ushistory.org/us/5.asp.

Wood, Betty. 2002. “Slavery in Colonial Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. Last modified

June 3, 2019.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/slavery-colonial-georgia.

Young, Jeffrey R. 2003. “Slavery in Antebellum Georgia.” Georgia Encyclopedia. Last modified

July 26, 2017.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/slavery-antebellum-geor

gia.