An Archival Study of Walnut Grove and the Young Family

A directed study under the supervision of Dr. Terry Powis at Kennesaw State University

By: Jennifer Billingsley

Introduction

The Walnut Grove Plantation is situated near the confluence of the Etowah River and Pettit Creek in Cartersville, an area rich with history. The history of Walnut Grove is far-reaching into the past, beginning in the 1800s with the arrival of the family of Robert Maxwell Young from Spartanburg, South Carolina. As a location for the Kennesaw State University Archaeology Field School taught by Dr. Terry Powis, some basic knowledge about the property and family has previously been compiled with a focus on the Civil War, the possible role of the Walnut Grove property during the war, and Pierce Manning Butler Young, a son of Robert M. Young, who was a Major General in the Confederate Army. Although we have some details pertaining to the Young family and Walnut Grove, there are still many gaps in the information, such as when the property was purchased, why the Young’s chose to move to Cartersville, the location of buildings that previously stood on the property, and how the property was passed down through the generations. This research seeks to find those missing pieces of information through letters, deeds, property maps, and factual documentation about the lives of the entire family and their home of Walnut Grove. This research seeks to use that information to bring to life the history of Robert M. and Caroline Young and their descendants through nearly 200 years, as well as their home of Walnut Grove that has been passed down through generations to their great- great-grandchildren today.

Methods

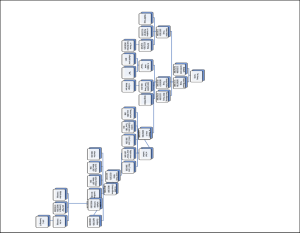

My research consisted of online resources such as Ancestry.com, accessing public records at the Bartow County tax assessor’s office, research shared by the Etowah Valley Historical Society and the Bartow History Museum, historical books, and research at Walnut Grove Plantation. The majority of the family lineage was researched through the use of Ancestry.com, an online heritage resource, with confirmation from the census records. Beginning with what was known, the names of Robert Maxwell Young, Elizabeth Caroline Jones and the Walnut Grove house, as well as the origin point of Spartanburg, South Carolina, it was possible to trace the family history to the descendants currently living in Cartersville (Figure 1).

Reading through the large collection of personal correspondence provided by the Etowah Valley Historical Society and the Bartow History Museum was beneficial in narrowing down specific events and occurrences in the daily lives of the Young family. Many of the letters detailed Robert Young’s search for property through Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, while others focused more on the details of daily life for the Young family, such as his role as a doctor, and schooling for the children. Every piece of new information was vetted for authenticity, by validating where the information came from, and cross-checking the facts through online resources and historically accurate books such as History of Bartow County, Georgia, and The Confederate Soldier in the Civil War. Detailed accountings of Civil War generals and maps showing troop movements were compared to determine the validity of troops occupying land at the Walnut Grove Plantation.

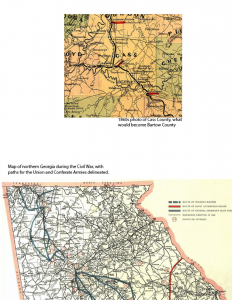

The lineage from Robert Maxwell and Elizabeth Caroline Young to John L. Cummings III was successfully documented with accompanying dates (Figure 1). Maps and first-hand accounts place the path of the Union army within an area of two miles or less of the Walnut Grove property during the Civil War (Figure 2). Recorded deeds, legal documentation, and the will of Robert Young have established the passage of the Walnut Grove property through the hands of family members to present day. Census records, personal correspondence, and legal documentation established Robert Young as one of few practicing doctors in the area, and a household that included approximately 11 enslaved Africans in 1860. Correspondence from the Youngs document their desire to seek a home in a more lucrative area close to a river. Photographs of the home in the 1800s and 1900s provide a comparison for the house as it stands today (Figure 3).

A Brief Synopsis

Robert Maxwell Young and Elizabeth Caroline Jones married in 1826 in Spartanburg, SC. Following an exhaustive search by Robert, his father-in-law, and friends, the Youngs found property in what was Cherokee and then Cass County, Georgia. They moved their four children Robert, George, Louisa, and Pierce, in the 1830s to Cartersville, Georgia. The Young family built their home from lumber and bricks, materials both purchased and found on the property, and they named their home Walnut Grove due to the abundance of black walnut trees. Robert was one of very few doctors in the area, and Elizabeth taught their children, took care of the peacocks, and ran the household. Two of their sons and their daughter married, and all three of the sons fought for the Confederate Army. When times became difficult after the devastation of the war, the Youngs turned to farming to survive. Pierce went on to become the first Democratic congressman of Georgia after the war. Additionally, P.M.B. Young represented Georgia in multiple Democratic Conventions, as a commissioner to the Paris Exposition, and was appointed consul general to Russia, as well as minister to Guatemala and Honduras. The daughter, Louisa, married Thomas Jones, Jr., and they had 5 children. Their daughter, Louise married J. C. Milner, and had 3 children. Their daughter Ella married a man named John Cummings, and they had a son named John “Skip” Cummings Jr. The home is currently held in trust for the son of John “Skip” Cummings Jr., John L Cummings III.

Here is where their story begins

Robert Maxwell Young was born June 5, 1798, one of 13 children born to William Young and Mary Solomons in Greenville, SC. His future bride, Elizabeth Caroline Jones, was born November 28, 1808, one of 11 children born to George Washington Jones, Jr. and Elizabeth Caroline Mills in Laurens County, SC. Robert pursued a medical degree and graduated medical school in 1821. Robert and Caroline, as she often went by her middle name, married in 1826 and lived in Spartanburg, SC. Though newly married, the couple were already planning for their future home, and contacted a builder for a quote to build a brick house (Figure 4). Unfortunately, life as a doctor in Spartanburg, SC was not very lucrative, and the couple decided to look for new land further south. During the 1830s in the south, land was being auctioned or sold in the land lottery. Robert began an exhaustive search, with friends, and also with his father-in-law, focusing their search in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. There are numerous letters written in Robert’s hand to his wife, Caroline, telling of his travels. Several letters, spanning three years, mention various accountings in the Southeast: February 13, 1833 from Marion, Alabama he speaks of the weather and difficulty in searching for property; April 9, 1834, he describes visiting his family in Decatur, GA; and October 24, 1835 visiting his family in Lawrenceville, GA. Correspondence by Robert to Caroline in November 20, 1835 from Columbus, Mississippi, he writes of a business arrangement to purchase land:

“Mr. Henry, Mr. Bobo, and myself, have entered into a large company to purchase land. There are about one hundred men belonging to the concern. Each of us have put in $500, and agree to sell the land which we purchase for cash in a few days. We do not expect to realize a great profit from this operation, but have no doubt but it was the best step that we could have taken” (R. M. Young, personal correspondence, November 20, 1835).

A follow-up letter to his wife nine days later, Robert confirms that he, Mr. Bobo, and Mr. Henry purchased land totaling 10,000 acres in Columbus, Mississippi, and planned to hold onto the property for one to three years, then sell it for profit. With his business concluded for the time being, he states that he will begin the 15-17 day travel home to Spartanburg, SC (R.M. Young, personal correspondence, November 29, 1835). Robert mentions in a letter to Caroline November 10, 1835, that he is looking specifically for large property near a river, and he focused his search with that in mind. Traveling by horse was time consuming and difficult, and he often found that by the time he arrived in an area, the best lands had previously been claimed. He wrote often to his wife E. Caroline during his travels, but as she was not an avid writer, many of his letters told of his despair in not receiving a response:

“Our fare is intolerably bad, and proving worse every day. The number of persons here is so great, and increasing daily, that I have some doubts whether the tavern keepers will be able to hold out in furnishing a plentiful provisions for them. I hope and trust that we shall be able to leave this in a few days. I never was more completely tired of a place in my life. I have been strangely neglected or have been peculiarly unfortunate in receiving letters since I arrived here. Mr. Henry, & Bobo get letters almost every mail. I am almost ashamed to go to the post office. I have enquired so often & been disappointed in receiving letters that I have almost lost the fond belief that I am remembered at Spartanburg. But this is a painful reflection give my love to George, Robert, Louisa & believe me your affectionate husband.” (R.M. Young, personal correspondence, November 20, 1835).

When Caroline did write to Robert and to various members of her family in White Oak, Rutherford, NC, she spoke of their children Robert, George, Louisa, and Pierce. Included in her correspondence were details of daily life. In one letter she tells her husband of a mishap of Louisa’s, when a chair fell and hit her in the eye. In another letter, dated February 22, 1838 from her family’s home at White Oak, she speaks of their youngest, Pierce, taking his first steps, “Little Pierce has just commenced to walking and is in better health than I have ever seen him” (Figure 6). She continues on to tell of her concern for Robert’s safety, “… while you are in that country”, and states, “….I have no doubt but the practice of the rail road will be very profitable to you, if you should get the appointment alone.” (E.C. Young, personal communication, February 22, 1838).

Though the exact details of the land purchase are unclear, Robert and Caroline became the owners of 50 acres of land in what was Cherokee County, Georgia. The accounting of how that 50 acres of land became a grand estate amongst boxwoods, hickory nut and stately walnut trees was later written following an interview with three of the Young’s granddaughters, by Francis Elizabeth Adair, whose family lived nearby and founded Adairsville, once an Indian settlement called Oothcalooga village. Adair describes the area as, “….a sloping knoll on the banks of the Petits Creek three miles southwest of C’ville near the Etowah River….” (F.E. Adair, personal notes, date unknown). She goes on to describe Robert’s initial arrival, “….in a caravan of covered wagons arrived here and took up his abode in the story and a ½ log hut of an Indian Chief….on the banks of Pettit’s Creek.” She writes of his being the only physician between Cartersville and Rome, which made his medical practice very lucrative while he also oversaw the work by the enslaved Africans to clear 50 acres of growth near the river, where they then planted cotton. After clearing land and planting, Young turned his attention to the building of his home, the completion of which would allow his wife and four young children, Robert, George, Louisa, and Pierce, to join him in Georgia. He is said to have hired twenty-five Irishmen for the approximately two-year undertaking of building the colonial red brick house with a balcony over the front porch of which he had dreamed. Robert insisted all of the building materials be made from resources located on the property. The lumber for the home was made mostly from the walnut trees, and clay for the bricks was gathered from the banks of the creek. Wooden pegs and square nails made of iron crafted in the blacksmith shop were used in assembling the structure. The bricks were dried in a kiln on the grounds, and lime was burnt and used as mortar between the homemade bricks. Much of the furniture was made from their walnut trees, by a man named Vital, who unfortunately drowned in the Etowah River during his employment. After two years of work, the stately home of “Walnut Grove” was complete and named for the abundance of walnut trees used in the building and surrounding the home.

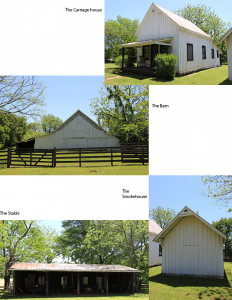

Other structures erected on the property alongside the home were a stable, barn, carriage house, and smoke house, all of which remain standing today (Figure 5). Once built, but no longer present were log cabins to house the approximately 13-28 enslaved Africans that were with the Young’s at Walnut Grove prior to the Civil War. The cabins were built in rows, with one family per cabin, numbering eight or more cabins. There was a woman who “weaved” and made cloth for clothing. One of the African women, “Aunt Satirah” was a nanny, and lived to be 100 years old, before she was laid to rest nearby.

Dated in 1838, a letter from Thomas Hamilton to Robert speaks of tending to a patient of Young’s while he is away, treating the boy “Billy” for cataracts, and of the return of a runaway. Mr. Hamilton speaks of the state of the crops at Walnut Grove, stating, “The crops of wheat and oats had languished much, are reviving and now promise a pretty fair crop except in such wheat as has been injured by late frosts” (Thomas Hamilton, personal correspondence, April 29, 1838). A relative of Caroline’s, Georgianna Jones, writes from Greenville to Caroline that she is happy to hear Caroline is “….pleased with your new home” (Georgianna Jones, personal correspondence, February 8, 1839), and in 1843 in a letter from Caroline to her brother, Caroline mentions living in a log cabin, and in a seemingly homesick letter from Louisa in Greenville, to her brother Robert, she says, “I am very anxious to see you all and would give all to be this night in Georgia in our old log house with you all” (Louisa J. Young, personal correspondence, February 14, 1846). Robert wrote to Caroline’s brother, Thomas, in 1846 that:

“….my family have, part of them, been very ill, Caroline and Pierce both have had severe spells of fever, and both relapsed, they are better now I am happy to inform you, both up and recouping quite fast. I have done a very heavy practice this season, & I hope it is about closed, this is the first day for the last 60 that I have not had frequent calls, this day not one. I have been uncommonly successful, I have not lost one patient that I have treated. I have treated over 100 cases of fever….” (R. Young, personal correspondence, September 27, 1846).

Robert continues in his letter that their sons Robert and George are off at a good school, 15 miles away, and they will be sending Louisa to school soon, possibly to Mont Peleiar, one of the earliest in the state to admit girls. Robert writes,

“I am doing every thing in my power to get Robert in at West Point, he is very desirous to go. He will make a good scholar if he has the opportunity. George is somewhat disposed to study medicine, he might make a good doctor, but he has a hard dislike to hard study. He is, however studying pretty well, but he loves farming far better. I don’t know how we are to get Pierce educated, his Mother can’t spare him nor can he spare his Mother, I expect that I shall have to board them both out for it seems that we never can have a school in the neighborhood.”

Within various correspondence was also discovered an unsigned note addressed to Dr. Young, dating to August 24, 1846, confirming that school fees for George and Robert will be paid by bacon, ham, lard, flour, and cornmeal. By 1850, George was 22 years of age, and had completed his medical degree becoming a physician despite his love of farming. Walnut Grove grew to encompass 800 acres of land, with 500 acres considered “improved land”, and the crops were wheat, rye, corn, and oats. Between the ages of 13 and 14, the youngest child, Pierce, left home to attend Georgia Military Institute in Marietta, GA. He graduated in 1856, briefly studying law, before being appointed to the United States Military Academy and attending West Point in New York in 1857. During that time, his older brother, Robert Butler, married Josephine Florida Hill in Walton, Georgia, January, 12, 1853.

While at West Point, Pierce writes home to his family about his growing difficulties being a southern student in a northern school when tensions are rising, and his concerns about a coming war between the north and south. In one letter, he writes that he will stay as long as possible at the school, though he fears he will be forced to leave soon before difficulties become more severe. While national tensions were rising, Louisa married Thomas Foster Jones, Jr. September 11, 1860 (Figure 7), and her brother George married Virginia Lamar and moved to nearby Resaca in 1860. In January 1861, Georgia’s secession from the Union brought Pierce home just two months before graduating, believing it to be the safest course, and desiring to join the Confederate Army (Figure 8). In a letter from George to his father in March of 1861, George advised Robert that it would possibly be in the family’s best interest to find somewhere safe away from Walnut Grove due to concerns of war and movements of the armies, and to leave the overseer, Jim Honnon in charge. Robert Butler, George, and Pierce joined different regiments in the Confederate Army in 1861. George became a surgeon in the 14th regiment, and Pierce was appointed Second Lieutenant in the artillery, then promoted to First Lieutenant. In July, Pierce was appointed as adjunct to “Cobb’s Legion” and in September was promoted to Major, then to Lieutenant Colonel in November in command of the cavalry of the legion. George made his way to West Virginia with his regiment, but was killed in battle September 20, 1861, leaving behind his wife, Virginia, and four children: Sarah “Carrie” Caroline, George William, Jr., “Bud”, and Lafayette Lamar. Robert Butler was a part of Nelson’s 10th Texas Infantry Regiment. The regiment was captured at Arkansas Post in 1863, their first major battle, then exchanged three months later before they were joined with two additional regiments to Patrick Cleburne. The regiment fought at Chickamauga and Ringgold Gap before once again becoming independent and fighting in the Atlanta Campaign, then at Franklin in 1864. On November 30, 1864, Colonel Robert Butler died of wounds received in battle at the battle of Franklin, Tennessee. Robert left behind his wife Josephine, and two daughters Maddie and Ida.

Pierce continued on with the Confederate Army, recognized for “remarkable gallantry” and promoted to Colonel, before participating in the Gettysburg campaign as cavalry operations. In August of 1863, Pierce was wounded when he took a ball to the chest, but the ball did not penetrate the chest. He spent his recovery in Richmond, then was promoted to Brigadier General in October. In December of the same year, he was promoted to Major General while he was actively engaged in the 1865 campaign in the Carolinas. In a letter Louisa wrote from Walnut Grove to her husband Tom, she told him, “….there is a prospect of our soon being rid of all the refugees” referring to several families that were boarding with them, she also mentions her brother Robert is “….suffering intensely from the heart” and fears he will die soon (Louisa Y. Jones, personal correspondence, May 28, 1863). Following Pierce’s wounding, there was another letter from “Lula” (Louisa) to her husband Tom in which she tells him the nature of Pierce’s injury and his convalescence in Richmond.

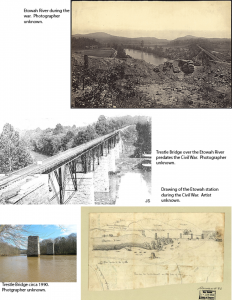

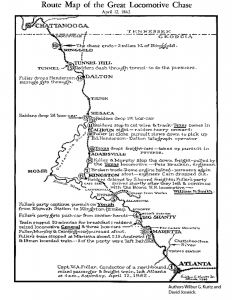

During the years of the Civil War, both Union and Confederate troops relied heavily on the utilization of the railroads to move troops, munitions, and supplies. Therefore, the few rail lines in existence at that time were of great importance to both sides. Troop movements could often be tracked by proximity to active lines, one of the most prominent being the Western and Atlantic Railroad, founded in December of 1836, running from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Marietta, Georgia for a total of 119 miles, with line and name changes at both the north and south ends. During the war, an extension was added from the Cooper’s Furnace Ironworks, across the Etowah River to the Etowah station (Figure 9). This railroad was made famous during the Great Locomotive Chase in April of 1862, during which it crossed the Etowah River several miles to the east of the Young property (Figure 10). The extension of the railroad was destroyed during the war and was not rebuilt. Due to the proximity of the rail line and nearby waters of the Etowah River and Pettit Creek, it has been suggested that troop movements likely crossed the Young property or possibly remained there for a time. In a hand drawn map of pencil, blue ink, and red ink, of the Etowah River spanning from Rome to Cartersville, showing possible river crossings and difficult terrain, Pettit Creek is clearly marked near to Rowland’s Ferry (Figure 11). Also marked is what appears to be troop movements, showing passage close to, or through, the Young property. Maps of the movements of the Union Army, the Army of the Ohio, reflect paths crossing the Etowah River to the east of the Young property, but within approximately two miles. An accounting of Lieutenant-General Joseph Wheeler of Georgia from the pages of “The Confederate Soldier in the Civil War”, from May 24, 1864, 7AM, “Not knowing the force guarding the train (at Cass Station)….I attacked with Kelly’s division, using one regiment to guard its right flank on the Kingston Road.” He continues, recounting the details of burning the enemy’s wagons, and the enemy becoming frightened enough to, “….burn a considerable train below Cass Station, and also similarly, destroyed a quantity of commissary stores recently brought to that point for transportation.” (La Bree, et al., p. 264). Wheeler details how he ordered the Eighth Texas and Second Tennessee to meet a rapidly advancing opposing force, and they drove them back, capturing more than 100 prisoners in the process. “I had previously detached a regiment to cut the railroad, and having, from the prisoners, citizens and personal observation, learned all regarding the enemy, I withdrew quietly toward the river, crossing with my prisoners, wagons, mules, horses, etc.” (La Bree, et al., p. 265).

After the war, Pierce returned home to Walnut Grove, intending to become a farmer. In 1868, he was elected to the US House of Representatives, where he served four terms as a Democrat, 1868-1875. After a defeat for a fifth term, he was appointed in 1878 as a United States commissioner to the Paris Exposition. After Paris, Pierce was appointed consul-general to St. Petersburg, Russia from 1885-1887, and then as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Guatemala and Honduras from 1893-1896.

On January 9, 1872, Robert M. Young had his last will and testament drawn up, stating that he was, “….being of sound mind, but advanced in age and infirm in body….” Naming his only remaining son, Pierce as the executor of his will, and specifying him to hold in trust for Caroline, “…..my plantation lying in the forks of Pettits Creek and Etowah River containing 560 acres more or less….” (Last Will and Testament of Robert Maxwell Young, January 9, 1872). Robert Maxwell Young passed away on January 13, 1880, at the age of 82 in Bartow County, the official cause listed as “paralysis”. He was survived by his wife Caroline, son Pierce, daughter Louisa, and 12 grandchildren. Robert’s wife, Caroline, followed him in death, four short years later, at the age of 78.

In the years following his parents’ death, while Pierce was away for his appointed positions, he contracted to lease out portions of the property and buildings at Walnut Grove. In October of 1885, one such contract between P.M.B. Young and James C. Waldrip outlined details for Young to rent a portion of the farm west of the watering place on the creek, south to the river, containing 200 acres, more or less. The land was leased specifying it was for cultivating for one to three years. Also included in the contract was a tenant house and outbuildings, west of the dwelling house with two acres and the portion of land from the old stables to the old cabins including the cabins amounting to three acres. Pierce also included three rooms in the dwelling house for sleeping apartments and the large cellar under the east end of the dwelling. The agreed upon payment would be $900.00 (Figure 12).

In their lifetime, Louisa and Thomas raised six children before they passed at 70 and 67 years old, respectively: Caroline “Carrie”, Emily “Emmie”, Thomas Jr., Mary “Mamie”, Louisa “Loulie”, and Virginia “Ginnie”. Loulie grew up and married James Christian Milner in 1902 at 29 years of age. Loulie and James had five children: an infant son, Louise, James Jr., Ella, and Lula. Sadly, only three of their children lived to adulthood, the infant son not surviving childbirth, and Lula who passed away before she was a year old. Louisa passed at the age of 44, the same year as Lula, and James lived to 1940, passing at age 60. Their daughter Ella married John L. Cummings, and from that marriage came John L. “Skip” Cummings, Jr., and Martha Jean. Skip married, and the couple had two children, who will one day inherit the stately home of Walnut Grove.

The elegance and history at Walnut Grove are apparent, at a single glimpse of the stately plantation home amongst the black walnut trees. One can almost see the colorful plumage of the peacocks and hear their raucous greeting calls, alerting family that visitors have arrived, much as they did in the 1800s. The Young family was one that knew adversity, happiness, challenges, and uncertainty. Yet, through it all the family persevered, survived, and thrived, just as their descendants continue to do today, inside the same walls built under the direction of Robert Maxwell Young over 183 years ago, and amongst the same black walnut trees that gave the stately manor house its moniker. Although reliable information regarding Walnut Grove during and immediately following the Civil War is scarce, the simple fact is that the sturdiness of the Young family and the home they built have withstood the test of time, and the walls still have many stories to tell, for those who are willing to listen.

Figure 1

Young Family Genealogy

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Parents of P M B Young

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Land lease contract

Acknowledgements

This research would have not been possible without the advisement, resources and educational expertise of Dr. Terry Powis. Additionally, I would like to thank the Cummings family for providing knowledge pertaining to the family and property, and for letting KSU students dig on their private property for the past few years. I would also like to thank Joe Head of the Etowah Valley Historical Society and Trey Gaines of the Bartow History Museum for allowing me to use their collected research and for providing their expertise pertaining to the history of the area.

***All historical documentation, artifacts, and historical belongings reside at Kennesaw State University. Walnut Grove remains a privately-owned home.

References

Adairsville City Page

https://www.adairsvillega.net/our-city

Ancestry.com

Year: 1880; Census Place: Little Rock, Pulaski, Arkansas; Roll: 54; Page: 287A; Enumeration District: 142

U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

Original data: Find A Grave. Find A Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi.

Year: 1930; Census Place: Cartersville, Bartow, Georgia; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 0023; FHL microfilm: 2340072

Year: 1940; Census Place: Cartersville, Bartow, Georgia; Roll: m-t0627-00638; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 8-8B

Census Records, Cass/Bartow County.

http://www.gabartow.org/Census/

Cunyus, Lucy Josephine. 2001. History of Bartow County, Georgia Formerly Cass. Greenville: Southern Historical Press.

Kurtz, Wilbur G. and Dave Joswick

http://andrewsraid.com/routelrg.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18004436

La Bree, Ben, et al. 1895. Confederate Soldier in the Civil War 1861-1865. Louisville: Courier-Journal Printing Company.

Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3924r.cws00081/?r=0.617,0.326,0.513,0.338,0

United States Federal Census Bureau in accordance with the National Archives