One can only surmise that in the years following the Civil War the saltpeter cave in Bartow County was a place of curiosity. Certainly, local residents who had enjoyed visits to the cave in earlier times and had been prevented from doing so by the extensive mining operation there began to return to the cave following hostilities. The cave had earned a place in history, being referred to in one newspaper article in 1884, in a description of the town of Kingston and environs, as “the celebrated Saltpeter cave” (Anon., Oct. 21,1884).

As Bartow County residents began to live normal lives again and seek out pleasurable leisure activities, trips out to the cave seemed to become commonplace, and descriptions of these trips found their way into newspapers of the day. Reading them affords one the opportunity not only to learn more about the cave, but also about life during that time period. Following are some of these articles. In quoting them the original spelling and wording has been retained.

IN SALTPETER CAVE

THE WONDERFUL CAVERN NEAR KINGSTON

A Merry Picnic Party Spend a Day There

The stillness of the summer afternoon around the mouth of saltpeter cave was broken by gay laughter as a merry crowd of picnickers gathered there to explore it. The massive natural masonry of the grand arched entrance fills the beholder with awe, and fits him to appreciate the subterranean wonders of the place. The descent to the grand reception room is some sixty feet down a winding and rugged way. As this descent is made the air grows perceptibly cooler, and when the bottom is reached one almost regrets that an overcoat was not brought along. The thermometer stood at about 95 that evening, but it was not over 65 in the bottom of the cave. Our little party was there to explore. About half of us had never been in the cave before, and we were particularly anxious to investigate, so, with a bright lantern and a flaming torch, with Mr. T.M. Smith as guide, we entered the darkness, which was so thick it could almost be felt. We entered first the large “Indian ball room” with its irregular walls and smooth floor, which seemed large enough to accommodate a thousand dancers. This must have been at one time a beautiful room before the sparkling walls were smoked black by the torches of explorers. From there we passed up a steep declivity and through a narrow passageway into a smaller, but more beautiful apartment. There were signs of stalagmites and stalactites, but most of them had been broken off and carried away by curiosity hunters. This room was also blackened by the smoke of the torch. It is impossible at this time to remember the names of the different rooms and apartments, but for one hour we wandered through the solemn and mysterious underground realm, at every step finding something to excite our wonder and inspire our awe. Sometimes rough, jagged rocks seemed to overhang and shut out our way, and we would abruptly turn aside into a beautiful chamber. Sometimes we would creep along half bent for some distance and suddenly enter a grand amphitheater whose roof was so far away that it was almost invisible. We wandered on and on, filled with a splendid admiration and awful reverence as the hidden mysteries of this place revealed themselves to us. “The Fat Man’s Misery”, “The Squaw’s Bridal Chamber”, “The Lover’s Leap”, “The Grand Column”, “The Chief’s Council Chamber”, “The Rock Bound Coast”, “The Miser’s Money Chest”, “The Dungeon”, and many other places of interest claimed our attention. It would require far more skill than the writer possesses to present a satisfactory description of the attractions of the cave. One could imagine that he was wandering through some ancient castle of irregular construction and careless design. The darkness lends it an air of weird loneliness. The spirit of laughter and jest that pervaded our crowd at the entrance had gradually died away, and the lights flared on solemn, awestruck faces. We had found our way back to the “Ball Room” and sat down to rest. Fortunately, there were several splendid voices in the party and they were disposed to sing. The song was started by a strong voice and the different parts were caught up by the little crowd. Not being musical we lay down outside of the circle and listened. The whole place became full of the music. It seemed that invisible choristers caught up the words, and from every room, and cavern, and grotto, and hall, and tower came back the echoing sound until the whole inside of the mountain was swelling and breathing with a grand chorus of a thousand voices. With our head resting on a stone we watched the little party of ten singers and wondered if so much music could come from them.

The lights had burned low and were flickering; the faces of the party looked strange and almost ethereal. It required very little stretch of imagination to people the cave with myriads of invisible singers whose angelic voices were aiding the singers around us to make up the mighty anthem that was surging and rolling through the cave. When the song was ended a silence fell on the singers, and the echoes were heard sobbing in the dim dark distance as if it were a requiem for the song. It was getting late and we hurried away to the place of entrance. Some of our company who had not gone in were gaily calling us to go. The light of the outer world burnt upon us, our dim lights went out, the gloomy, tomb-like feelings of the cave left us as readily as we pull off a wet rubber coat, and as we climbed out into the light some of the younger members of the party burst forth with “There’s gold in the mountain, there’s silver in the mine,” etc., and we soon found ourselves as merry as when we entered. Saltpeter cave is truly a wonderful place. There are hundreds of people who live and die in Bartow county who have no conception of its grandeur. We advise our readers to see it. No description can give an idea of its interior. It is not only beautiful, but picturesque and grand (Anon., September 2, 1884).

Of particular interest in the above article is the list of names that had been given to various formations and areas in the cave. These names had evidently been passed down, some of them possibly from Native Americans or at least persons exploring the cave with members of the indigenous population years before. This is typical of an article written by someone in a group of partiers, as opposed to a trip into the cave for the purpose of exploration. A month after this article, another was published in the same newspaper:

BARTOW’S WONDERFUL CAVERN

A Description of the Favorite Resort of

Picnic Lovers in Our County

There are many points of interest in Bartow county, but the most remarkable and interesting one is situated about ten miles from Cartersville. We refer to our justly celebrated Saltpeter cave. The adjoining country around it is poor, rocky and mountainous.

Following this beginning to the article, the writer then proceeds to totally plagiarize the writing of Rev. George White in his 1854 article in Historical Collections of Georgia:

The descent is steep, abrupt, and somewhat difficult, for perhaps one hundred and fifty feet, where the bottom becomes perfectly smooth and even, owing, no doubt, to the collection of dirt which has been washed down the mouth, and settling there for ages. This smooth and even surface extends forty by sixty feet. Here the Indians are said to have been in the habit of meeting for the purpose of dancing,

and to indulge in other customary pastimes and festivities.

The air is damp, and unpleasantly cold. From the mouth to the bottom of the first descent, the aperture becomes larger and larger until the bottom is reached. About midway the rocks overhead are so far above as to render the top almost invisible from the light of the torches. Stones thrown up can barely reach it. At the bottom of the first room, as it is usually called, the rocks close in on all sides, except the entrance, and a few feet through which the visitor must pass half bent, if he desires to proceed farther. After going in this way for twenty or thirty feet, the opening again becomes suddenly large and extensive on all sides, and a steep and rugged ascent has to be encountered for eighty or one hundred feet. Here, if it were not that the cave is

in the side of a mountain, it could not be very far to the surface of the earth above, as it is now ascended a distance equal to that which was descended in entering, and it is also some distance to the rock overhead. But the visitor is now in the heart or centre of the mountain, where no ray of light ever found its entrance, except that of the torch or lantern of exploring man. At the top of this ascent a road branches off to the right and left. Both are circuitous, and lead into various rooms of different

sizes and shapes. The one to the right leads by a difficult and sometimes dangerous route, to the longest room in the cave. From this there is a small and narrow outlet, scarcely of space sufficient to proceed erect, of about one hundred and fifty or two hundred feet in length, and leads to another issue, though small.

There are in this cave some twenty or thirty rooms of different sizes and forms, and generally connected with each other by apertures sufficiently large to admit of easy access; but in some places, though rarely, the visitor must gain his way on hands and knees. Some visitors, of more enterprise and perseverance, have taken in poles, by which to ascend to the rooms overhead. The continual drippings of lime and saltpeter have, in many of the rooms, formed beautiful columns and pillars, by concretion. Many of these, from the different shapes which they have assumed, are interesting curiosities. These pillars are, in a state of nature, almost as white as marble; but the frequent visits to the cave, and the visitors using pine for torches they have become smoked black.

Several years ago, considerable quantities of saltpeter were manufactured from the dirt dug out of this cave, and the signs are yet visible, but no operation of the kind is now going on. (Anon., October 21, 1884)

And the “picnic lovers” did come to the cave. The newspapers of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century are replete with announcements of family or church excursions to the cave, usually centered around a picnic, and almost always referring to it being such a cool spot on a hot summer day. These articles provide an important historical record due to the names mentioned in them. Typical of these articles are the following, sometimes announcing an upcoming trip:

A party of about twenty couples from here [Cartersville] will picnic at saltpeter cave tomorrow. It will be a jolly crowd, and we anticipate for them a delightful day (Anon., August 5, 1885).

Others gave a report after their trip:

Another pleasant pic nic came off at the Salt Petre cave on the 20th. Misses Howard and her guests. I noticed in the party Mrs. Crockett. Of Nashville, Tenn., and her sister, Miss Dearing, of Adairsville, also, Mr. Alex Capers, of Adairsville and Miss Addie Beltzelle, of Woodtown. It was quite a pleasant party (Anon., August 25, 1886).

A party of young people of Cartersville had a most delightful picnic at saltpeter cave last Saturday, and when the feast was spread and the young folks had assembled to partake of the bountiful repast Mr. John H. Dobbs and Miss Tennie Bell Dunn announced to the party that they had quietly journeyed to the home of Dr. W.H. Felton en route to the cave, and having prepared for the occasion with the necessary papers, were happily joined in the holy bonds of wedlock by that distinguished gentleman (Anon., July 19, 1894).

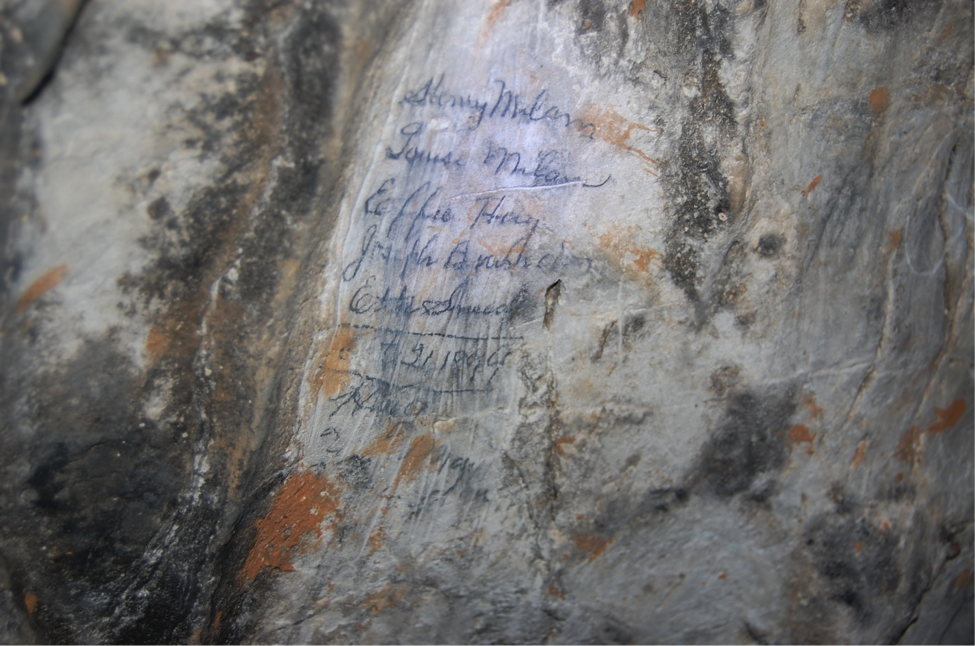

In addition to the numerous newspaper articles about social trips into the cave, several hundred names have been inscribed on the cave walls, often giving date visited and where the person was from. These have provided a great historical record, and local family names such as Milam, Archer, Adair, Goulding, Jolley, and Mullenix give mute evidence of trips into the cave.

Names recorded by a group visiting the cave on October 21, 1894.

One interesting inscription is “Mary Munford”, with the date August 23, 1879. This would be the Mary Munford who was born on May 25, 1879, and who was either taken to the cave as a baby, or, more likely, one of her parents visited the cave and commemorated her recent birth therein. Mary was the Library Chairman in Cartersville, and when the library was built in 1903 it was named the Mary Munford Library. She died unexpectedly on June 8, 1903 and was buried in Cartersville in the Oak Hill Cemetery. The present Cartersville Library has a room designated the Mary Munford Room.

In addition to the trips out to the cave for social gatherings, trips began to be made for more exploratory or scientific purposes. The following article from 1887 gives a very good description of the cave as the writer describes features that are readily identifiable today. I have annotated names in brackets by which these features are known to us and are shown on the map of the map.

Rome, Ga., June 14. – Mr. W.G. Cooper furnishes to the Detroit Free Press an interesting article on a cave in Bartow County, in which he says: “Within a mile or two of Sherman’s route to Atlanta, there is in Bartow County, Ga. a cavern of considerable historic interest. We first hear of it in 1835, when a handful of Cherokee Indians, who had incurred the displeasure of a band of highwaymen known as “The Pony Club”, found refuge in the cave until they were rescued by some regulators. In those days the walls and roofs of the passages were white, and their stalactites rivaled in beauty the icicles which formed about the mountain cascades; but since the workmen, in getting out saltpeter for the gunpowder of the confederate army, built great fires of pitch pine, and filled the cave with smoke, those dark passages and gloomy chambers, with their rocky walls, give one the impression that he is approaching Vulcan’s forge, and the black stalactites in all their fantastic shapes seems to be the handiwork of that grim artisan. Though these objects do not resemble thunderbolts, some of them have been knocked off and made into bolts no less destructive. Of late Vulcan seems to have abandoned the place to Pluto, who made his presence known last year by tearing up the floor and breaking a pillar in the lowest chamber. There was no other creature in the cave but a winged beast which loved darkness rather than light, and must have been one of Pluto’s little angels.

“The approach to the entrance is by a lonely road between wild hills, whose aspect is so cheerless, and the sighing of the wind in their thickets so mournful, that a man almost believes he is going to an awful doom. After going up the hill for a hundred yards, one is suddenly confronted by an opening ten feet square, and had a skull and crossbones been placed above it, he could not look into that dark and broadening abyss with darker and more infernal passages, without feeling a cold horror at the thought of exploring Hades.

“With a good reflecting lamp we descended a rough incline at an angle of forty-five degrees, until we were seventy-five feet below the opening. The roof was not so much inclined, and the mouth widened to sixty feet at the bottom, so as to form a large chamber. Beyond this the floor was smooth and the roof only twelve feet high. At this place pioneers have often danced, and it is known as the “ball room”. From there we passed through several large rooms, one of which was nearly 100 feet wide, with a roof fifty feet high in one place. The floor was strewn with rock fragments, and in passing out we had to climb round rough bowlders. After ascending a steep, slippery place for about fifteen feet, we were confronted by an immense stalagmite in the shape of a cone, eight feet in diameter at the base and twelve feet high [BBQ Pit]. Above it a cluster of stalactites resembled a chandelier. On the right and left were openings into a small chamber, behind the cone. Returning thence we went up the main passage at an angle of forty-five degrees and came to a circular group of stone icicles six to eight feet long. They reminded me of the illustration of the “Saracen’s tent” of Luray cave [Luray Caverns, Virginia], and one of them by itself formed a horse’s leg with knee and thigh almost perfect [The Elephant]. Passing several pillars and a smaller cone we descended by steps cut in the rock to a chamber with vaulted roof and level floor [Test Pit Room]. Directly over the entrance was a hole twenty inches in diameter and about six inches deep. From this place a very low arch twenty feet wide let us into a passage [1858 Passage] connecting with the main entrance. Returning to the big cone we passed through a large room full of rock fragments into a chamber from which we ascended by a fifteen-foot ladder to a small hole large enough to crawl through [Rimstone Rockway]. From it we emerged into a long passage at the end of which daylight appeared. Fifty yards farther in that direction was the “Jug”, formed by a stalagmite three feet thick and six feet high, with a neck formed by a pendant from the roof. The handle had been formed in the same way and was afterwards broken off by some explorer. At the foot of the jug was a small spring of clear, cool water, which was very refreshing after two hours of hard climbing. A few yards further we ascended sixty feet by an incline and came out of the small entrance. The air above ground seemed very oppressive, and we were glad to sit down and eat our lunch. Afterwards another hour was spent in exploring a passage on the right of the main entrance. After following it for fifty yards we came to a deep pit with a passage around one side and a shelving ledge on the left. By climbing cautiously around on the ledge we got into a chamber walled in by masses of stalactites [Margaret Mitchell Loft], and overhead a chandelier was formed by a cluster of those wonderful stone icicles. The two entrances were separated by a huge pillar ten feet thick, evidently formed by drippings. Afterwards we descended on the right of the pit into the “earthquake room” [Devil’s Dungeon], where there were unmistakable signs of a slip. On the right the inclined roof had descended and forced some of the stalactites into the floor, breaking and pushing up the clay for several yards. About a rod from this there was firmly attached to the floor and the roof, a pillar seven feet high and twelve inches thick. It was certainly formed by dripping as the union of the portions which grew from above and below was distinct. It had been forced at least fifteen degrees out of its original perpendicular position, and there was a fracture near the roof. The top of the pillar was moved twelve inches though still attached to the rock at the original place. From this it was evident that the relative position of the roof and the floor had been changed ten or twelve inches. This cave was visited last year by a party from the Smithsonian Institute, but as they remained only a short time it is probable that some of the most interesting features escaped their observation. There were other passages which the earthquake seemed to have closed” (Cooper, 1887)

One caving trip in particular in the early part of the twentieth-century bears mentioning, as much for who wrote the trip report as for what was contained in the article. In the Atlanta Journal on January 21, 1923 there appeared an article written by a reporter whose byline read Peggy Mitchell, a writer who would later write a famous novel, Gone with the Wind, under her given name of Margaret Mitchell. Ms. Mitchell’s account of her journey through the cave is both amusing and enlightening, and the vivid description she gives makes it possible to follow the route that her party took step by step:

THROUGH THE CAVE OF THE LOST INDIANS

Atlanta Party with only a twine string to guide them back to safety, explore immense Saltpeter cave near Cartersville, Ga. into which Redskins vanished years ago

By Peggy Mitchell

“Well, you see it was this way. The whole tribe of Indians went into this cave and none of them were ever seen again. Must have got lost in there and died or they might have come out at the other end of the cave miles away – if there is any other end – and never been able to find their way back out again”.

And then pleasantly, began an adventure , most pleasantly in fact, for one who had never entrusted one’s life to the mysteries of an unexplored cave and who was on the point of doing that very thing when the fate of previous visitors to the cave was learned.

Happy thought! The Indians went into the cave. We are now going into the cave. The Indians never found their way out again; we – cold chills.

The cave is in Bartow County, a short distance from Cartersville, and it is an enormous thing. It is said to extend for miles underneath the mountain. Saltpeter cave is the name that has been given it and the popular belief is that it was the scene of tribal ceremonies of the Indians and was a refuge for them in time of war.

Indians Lost in the Cave

So much we learned from Jack Darnell of Cartersville who has made a geologic study of part of the cave, and was kind enough to act as our guide. He had told us how the cave was believed by some to have been used formerly as a mine for saltpeter and how its formation indicated the outcropping of limestone rock such as is seldom found in north Georgia.

And then, just as we arrived at the entrance of the cave, he told us the legend of the Lost Tribe.

The legend is that a Cherokee tribe hard pushed by the fierce Creeks sent their wives and children into the cave for safety. Finally, unable to withstand the onslaught of their foes, the braves retreated into the black depths too. The pursuers, thirsting for slaughter, followed close behind and the earth swallowed them all up.

Where they went, no one knows. The cave runs for miles under the whole mountain, and the turnings and twistings are so numerous and bewildering as the Labyrinth. Pits yawn open suddenly underfoot; underground creeks cross the narrow paths. The Indian women probably wandered for miles waiting for their braves who never came to rescue them. The two tribes met in battle perhaps in the torturous windings of the cave’s depths and fought to the death – victors and vanquished alike, lost in the Stygian darkness miles underground. Perhaps the survivors starved in the pits. At any rate they never emerged into the light of day.

Like the Indians

Personally I never had much use for Indians, but when I stood at the mouth of Saltpeter cave, I had a fellow feeling for them. Like an enormous well, it opens up its slimy moss-covered sides down two hundred feet to where the floor of the cave gleams up faintly while in the shadowy gloom. One side rocky and treacherous underfoot was almost perpendicular, but capable of being descended if care was exercised in foot-holds and hand grips. As we climbed down, dislodged rocks rattled from their places and gathering momentum, crashed down the steep sides to the bottom with eerie echoes. A disquieting idea of what a slip would mean did not make us more comfortable on the downward trip.

Once at the foot of the steep incline, a large room opened up abruptly. The stone floor underfoot was smooth and cold. The passageways were chilly and damp. Two hundred feet above, the blessed daylight shown feebly through the opening in a small patch, like the lurid paintings in Dante’s “Inferno”. The limestone walls rose sheer – and while disappearing out of sight into the rock roof, somewhere in the darkness above. This room is known as the “Dance Hall” because of its smooth floors, but dancing was the furtherest thing from anyone’s mind at the time.

From this room branches off a dozen low openings in all directions, black mouths yawning uninvitingly.

If the String Breaks…

“We’ll try this one first”, said our guide briskly. “Yes certainly”, I agreed gulping as I saw the low small opening in the flair of the torch.

The tall men had to stoop to enter this passage, and it was so narrow that the damp walls brushed my shoulders leaving them muddy. The low ceiling dripping water down one’s neck is not conducive to optimism.

Once in the passage the guide paused and fastened a thin thread to a rock unrolling the thread from a ball as he walked ahead. The flaming pine knot lighted up the blackness.

“Be careful about stepping on the string”, he advised. “If it breaks we are out of luck, for there won’t be any way out”. Happy thought! Suppose some of the men stumbling in the dark behind me should break that fragile thread that was our one connecting link with the outside world! If it should break and we were lost I wonder how long it would be before searching parties were sent to dig us out. Exactly where I pondered, should they begin to dig! Suppose they dug at the wrong place.

Someone stepped on the string and the guide growled a warning which was echoed by a burst of shouts from the nervous members of the party. That thread was so thin!

After an eternity of stooping and rubbing the walls, the cave opened down into a pit-shaped room. With a sigh of relief the party came to a halt, bringing to bear torches and flashlights on the walls.

Twenty feet from the ground was a hole on the wall barely big enough for a man to crawl through. A plank, slime covered and rotten looking stretched from the floor to the aperature where intrepid souls had conducted explorations before.

Search for the Stalactites

“Never have been up there”, said the guide, handing his torch and ball of twine to Mr. Sperry. “I’ll go see what its like”. “Brave soul”, thought I, shivering in the dampness. Straddling the plank, he hitched himself gradually up it, and as we watched him in awe he disappeared into the dark hole with a wriggling kick.

Suppose, thought I, there is a pit on the other side of the wall and Mr. Darnell has fallen into it! We waited in silence. We could hear the rush of underground waters and wondered if it were possible to slide through the hole into it. I was glad that it was the guide and not me who was daring the unknown. Suddenly, his head reappeared. “I think that there are stalactites up here”, he said. “Come on up”, and he crooked a finger at me. “Really, I don’t care for stalactites”, I managed to say. “Oh, but you shouldn’t miss them. Not afraid are you?” Afraid? Oh, no. Only terror smitten. “I’ll come up”, said I, shoving my flashlight into my pocket, and straddling the plank even as he had done. But the plank was an inch deep in the accumulated slime of years and every hand hold slipped loose. I would crawl up a few inches and slide back. Finally, with the aid of enthusiastic “Boosters” I wormed my way up to the top of the plank where the guide grabbed my wrist in a muddy hand. He jerked, his hand slipped as if greased with lard and with a crack my chin hit the plank and I tobogganed down on my face. Cheered on by the assembled crowd, I was boosted up again and again the guide grasped me. This time he took no chances, but wrapping one leg around a stalactite – or a stalagmite (I didn’t ask which) to steady himself, he caught me by the collar of my shirt and he dragged me, gasping and squirming on my face, through the small hole and in over the oozy slime of the cave’s floor.

Like an Immense Church

This room was darker, if possible, than the one before; and having given up all hope of ever seeing the daylight again, I sat in a puddle of mud and flashed my light at the walls. The walls opened up like an immense church, with the vaulted roof curving above. Huge white columns of stalactite rose on all sides like the pipes of an enormous organ. The flashlight cast ghostly shadows. Bats, hanging by their toes in clusters like chandeliers from the roof squeaked and flapped as I probed them with my flashlight. “We are going on”, called up Mr. Speery. “You all follow the string”. Going on! Leave me in that slimy, oozy, batty hole? Never. “Wait!” I yelled frantically, and rushed for the hole.

The gibbering bats flew in my face as I slipped in the muck, and the roar of the hidden creek seemed perilously near. Once at the hole, the problem of getting down the intervening twenty feet confronted me, but my anxiety to get down overwhelmed everything else, seating myself on the board. I was preparing to edge down when my grip slipped and away I went whizzing, landing at the feet of the waiting crowd and knocking the ball of twine out of Mr. Speery’s hand.

My descent livened up the party, as they all volunteered to scrape the slime off me. But my main object was to get out – out in the daylight where people are supposed to stay.

The windings on the way back were everlasting it seemed, and I began to think that we, as well as the long suffering Indians, were in the cave for “keeps” when the dim patch of daylight opened up above like an answer to prayer.

Let the ghosts of the Creeks and Cherokees keep these “caves measureless to man”. They are welcome to them (Mitchell, 1923).

Photographs of the cave’s entrance and of the exploring party entering the cave illustrated the newspaper article.

We have named the upper chamber into which Ms. Mitchell climbed the “Margaret Mitchell Loft” when we mapped the cave, in honor of her exploits (that room had previously been referred to as the “Organ Loft”). Their party was never very far from the entrance – when she was in that room, she was only about twenty feet from daylight, through another crawlway; at the base of the climb up, where she used the plank for access, they were only some one hundred feet from daylight, via the route they traveled. While the stalactites in the Loft apparently survived the saltpeter mining untouched, as they were in an area of no sediments to mine, they are now blackened and broken.

References Cited

Anonymous. 1884b. Bartow County Towns. Cartersville American, October 21, Vol. III, No. 25: 3.

Anonymous. 1884a. In Saltpeter Cave, the Wonderful Cavern Near Kingston. Cartersville American, September 2.

Anonymous. 1884c. Bartow’s Wonderful Cavern. Cartersville American, October 21, Vol. III, No. 25.

Anonymous. 1885b. Cartersville American, August 5.

Anonymous. 1886b. Cartersville American, August 25.

Anonymous. 1894. The Courant American Newspaper, Cartersville, Georgia, July 19:1.

Cooper, W.A. 1887. Atlanta Constitution, June 15: 3.

Mitchell, Peggy. 1923. Through the Cave of the Lost Indians. The Atlanta Journal Magazine, January 21: p.11.