Rap Dixon

The Fight to get Bartow’s Negro Leagues Standout into Cooperstown

By Nicholas Sullivan

Article was reprinted by permission of the Daily Tribune News.

Bartow County has produced plenty of outstanding athletes over the years, but few locals probably are aware that the greatest baseball player to ever call the county home is a hall of fame-worthy talent named Herbert “Rap” Dixon.

Born September 1902 in Kingston, Dixon, like every Black player in his day, was forced to ply his trade in the infant Negro Leagues due to segregation within baseball. Across the 1920s and into the ’30s, he established himself as one of the best outfielders — in any league — of his generation.

“His legacy is enormous,” said Ted Knorr, who should be considered the foremost authority on Dixon’s career. (Founder of the Negro League Research Conference, Harrisburg, PA)

.

A resident of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Knorr has spent a large portion of the past few decades advocating for what he believes is Dixon’s rightful place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Knorr even runs a Facebook page called “Rap Dixon for the Hall of Fame.”

“There’s plenty of room for more Negro League players to be an educational citadel, like it’s supposed to be at the hall of fame,” Knorr said. “People coming through that museum learn about baseball, and right now, they’re not learning about the first half of the 20th Century.”

Dixon, who died in Detroit at age 41, reportedly began playing semi-pro baseball as a teenager, possibly as young as 13. He played for the Keystone Giants in Steelton, Pennsylvania — where his immediate and some extended family moved some time after 1910, in the early stages of the Great Migration.

According to Knorr, included in the group who moved from Kingston to the Harrisburg area was Dixon’s younger brother, Paul, whose granddaughter India Holland-Garnett is Dixon’s closest known living relative.

Also in the traveling party, per Knorr, was James Goodwin, Dixon’s uncle. James Goodwin is the grandfather of former MLB outfielder and current Boston Red Sox first-base coach Tom Goodwin, making the younger Goodwin the first cousin, once removed, of Dixon.

Similar to many fellow Negro Leagues stars, Dixon’s exploits bordered on legends, which fair or not plays a part in the electability of an athlete current voters never got to see play. But even his verifiable statistics and his contributions to the game at large grant Dixon strong consideration for a place in Cooperstown.

“A complete ballplayer, Dixon also ranked among the best defensive outfielders,” reads part of his bio on the website of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. “He had good speed and range, was a good judge of fly balls, and had an outstanding throwing arm. …

“Although sometimes temperamental, Dixon was an intelligent hitter, and hit for average as well as for power, finishing with a lifetime .340 batting average in league play and a .362 average in exhibitions against major leaguers. In 1933, he was honored by being selected to participate in the first East-West All-Star game ever played.”

The Negro Leagues were officially established Feb. 13, 1920, in Kansas City, Missouri. In anticipation for the 100-year anniversary, a Centennial Team was created — consisting of 30 players, a manager and an owner — and Dixon was on it.

“These players were the best to play in professional baseball outside of Major League Baseball [MLB] prior to integration in 1947,” reads part of the description under a postcard set of the team. “Committees for the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown have voted nearly all the members of the Centennial Team into the Hall of Fame.”

But not all of them are enshrined, yet.

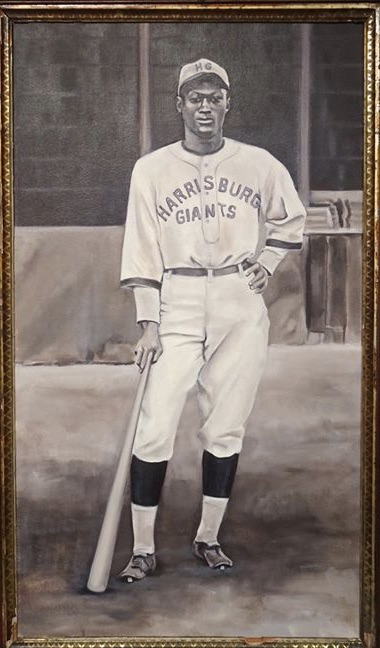

During the mid-’20s, Dixon, who hit and threw right handed, played for the Harrisburg Giants and helped form arguably the best outfield trio baseball had ever seen alongside Oscar Charleston and Fats Jenkins on the grass at Rossmere Base Ball Park.

More than 40 years later, Knorr graduated from Lancaster Catholic High, not knowing until later that the school was built on the site of the old baseball field.

“That connection between my high school, the field and then the Harrisburg Giants is probably what first brought Rap to my attention,” Knorr said. “Living in Harrisburg, you hear these stories about the Giants in the ’20s, and I just fell in love with Rap.”

Per his NLBM bio, Dixon spent one winter with an all-star team that played exhibitions around the Pacific Rim. During the tour, he was credited with hitting the longest home run ever in Japan and was given a cup by the emperor of Japan, honoring him for his performance.

The pinnacle of Dixon’s stateside career — in terms of both team and individual success — came in 1929. That year, he led the Baltimore Black Sox to the American Negro League title, hitting .432 with 16 homers, 25 stolen bases and a .784 slugging percentage.

During the course of that season, Dixon put together one of the most incredible streaks in the history of the sport, racking up 14 consecutive hits without recording an out — two more than the MLB record. Perhaps most remarkably, according to Knorr, the streak began a day after Dixon was hit in the head by a pitch (in a time before helmets) and had to be carried off the field.

“This is his hallmark, these 16 plate appearances, because he also draws two walks,” Knorr said of the streak. “He goes 14-for-14 with a bunt single and a home run. He showed all his talents. … That’s his greatest achievement.”

As his résumé would suggest, Dixon played in some extremely important games over the years. However, the most impactful set of games might have taken place 90 years ago inside old Yankee Stadium. Even though the historic ballpark had only been opened for seven years, the New York Yankees had already won three World Series titles in that span, making it one of the most well-known venues in baseball.

On July 5, 1930, Dixon’s Black Sox competed in a doubleheader against the New York Lincoln Giants, marking the first contest played between two Black teams in “The House That Ruth Built.”

According to an article in the Pittsburgh Courier, 20,000 fans attended. Per Lawrence D. Hogan, a Union County College professor who consulted on Cooperstown’s African American baseball exhibit, ticket sales that day raised $3,500 to benefit the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful Black labor union in the country.

In an essay published by the New York Times entitled “The Negro Leagues Discovered an Oasis at Yankee Stadium,” Hogan wrote, “The Negro Leagues presence at the Stadium continued through the 1930s and World War II, and beyond the integration of the majors in 1947. When the Yankees were on the road, Negro Leagues teams played there regularly before large crowds; the Black Yankees called the Stadium their home for several seasons.”

That historic day, Dixon belted a first-inning home run in the opener, becoming the first Black player to ever clear the fence in the park. For good measure, he went deep twice more in the second game to help his team salvage a split of the doubleheader.

Dixon’s impact on the sport extended beyond his impressive playing career, which saw him suit up for roughly a dozen clubs, and into his coaching tenure.

According to Knorr, Dixon led the Trujillo All-Stars, featuring hall of famers Cool Papa Bell and Satchel Paige, to a tournament title in Denver. He also coached an integrated team, including a few white players, in 1942 — five years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. As a manager, Dixon is even credited with helping kickstart the professional career of future hall of fame inductee Leon Day.

Dixon, himself, was a finalist for the hall in 2006 — the most recent time Black players from the Negro Leagues and pre-Negro Leagues era were chosen en masse. Knorr, who is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) and on their Negro Leagues committee, did statistical research for the candidates leading into the 2006 vote.

While Dixon didn’t make it, the vote wound up nearly doubling the number of representatives from that era, as 17 honorees joined 18 previously enshrined individuals. Unfortunately for Dixon and the others who came up short 14 years ago, the hall hasn’t voted in any Black players from that time period since then.

The hall’s Early Baseball era (Prior to 1950) committee is scheduled to vote on possible nominees for the Class of 2021 in December at the MLB Winter Meetings. The next meeting for the committee won’t be for another 10 years.

Between 2020 representing the centennial anniversary of the Negro Leagues and the conscious effort by several prominent segments of American society to strive for long-overdue equality, there would seem to be no better time than the present for baseball to make a statement.

It can start by voting Rap Dixon and his deserving contemporaries into Cooperstown.

“They need to take some affirmative action,” Knorr said. “Only two [of the era’s 35 inductees] — Ray Dandridge and Rube Foster — got in under normal circumstances, competing against white veterans to get in. The other 33 went in under heavy affirmative action.

“The hall — right now, to the best of my knowledge — is planning no such thing, and this is 2020. … Never has this country seen more opportunity for healing than in this year, and the hall of fame could be part of it.”

Nicholas Sullivan is a sports reporter for The Daily Tribune News in Cartersville, Georgia. A version of this article originally appeared in the July 5, 2020, edition of the DTN.

Also see article on Bartow’s Preston Rudolph (Rudy) York, MLB Hall of Fame,

BIBLIOGRAPHY

2006 Baseball Hall of Fame inductees, BaseballHall.org

Eras Committees, BaseballHall.org

Final Ballots Announced for Negro leagues and Pre-Negro Leagues Candidates, Negro League Baseball Players Association [nlbpa.com], Nov. 21, 2005

Herbert “Rap” Dixon profile, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum [eMuseum]

Hogan, Lawrence D., The Negro Leagues Discovered an Oasis at Yankee Stadium, New York Times [nytimes.com], Feb. 12, 2011

Negro Leagues Centennial Team Postcard Set, NegroLeaguesHistory.com

Nunn, William G., Diamond Stars Rise to Miracle Heights in Big Game at Yankee Bowl, Pittsburgh Courier [clipping on Newspapers.com], July 12, 1930

Ted Knorr interview by Nicholas Sullivan

Tom Goodwin Statistics and History, Baseball-Reference.com