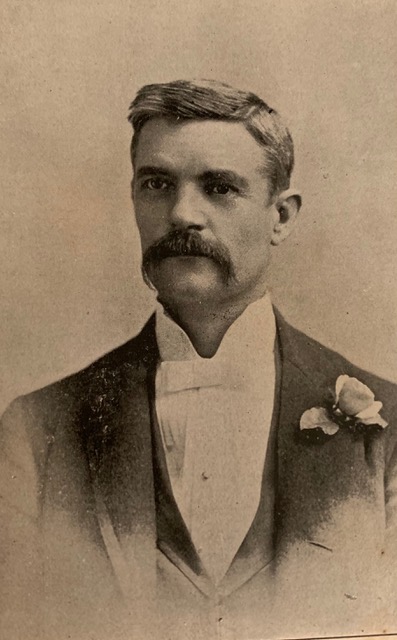

Rev. Sam P. Jones

Wonder of the Congregations

By Rev. Scott W. Shepard, PhD

Reverend Sam P. Jones

Seventy-one years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the birth of a nation, three mothers welcomed three baby boys into the world who would all make front page headlines 100 years after their births. The first was Thomas Alva Edison of Ohio who filled the universe with a pageant of light. Alexander Graham Bell of Scotland was another, who invented the telephone and made next door neighbors out of the inhabitants of the world. And on Saturday October the 16th, 1847, John and Nancy Porter Jones welcomed their second born son and gave him the name Samuel, who would one day flood the land with fluorescent spiritual light and would preach from the pulpit in conversational tones, like serious-minded business men talk over their phone in their private offices.

Samuel Porter Jones was born just across the Georgia-Alabama line in a small town withthe rustic name of Oak Bowery, Alabama, which has since Gone with the Wind. It has been well said, “Great childhoods last a lifetime.” Samuel Porter Jones’ Christian childhood would indeed last him a lifetime and would one day take him to national prominence as a Revivalist in America during the nineteenth century. The Jones’ family came from a long, rich, godly heritage.

Sam Jones’ paternal side of the family provided him a rich Christian Methodist heritage. His great-grandfather and his grandfather were both Methodist ministers. His grandfather, for whom he was given the name Samuel, preached for sixty years. Sam Jones had four uncles who were licensed preachers: Rev. Robert Jones, Rev. William Jones, Rev. Parks Jones and Dr. J. H. Jones and two brothers, one more notable than the other, Sam’s brother, Rev. Joe Jones.

His father, Captain John J. Jones, felt that he also had been called to preach. John and Nancy Porter Jones were a God-fearing Christian couple, both were of the Methodist faith and they raised all their children in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. Sam Jones would later say as a grown man, “I am a Methodist just like I am a Jones, and, if it is a sin to be either, it is a sin that is visited upon the children from their parents.” Sam Jones’ mother especially shadowed a tremendous presence over her son, in fact, over everyone that knew her. She was affectionately known by “Queenie” because everyone said that she carried herself so very regally.

While Sam Jones attended his first school in Chambers County, his teacher, W. F. Slaton made an indelible mark upon his young mind. Slaton, who later became superintendent of the Atlanta Public School System, wrote a speech for the five-year-old and gave Sam his first exposure to public speaking. Slaton had penned the words for him and Sam’s mother had assisted in establishing those words to his memory.

As the school’s regular Friday afternoon speeches wore on, young Sam Jones had fallen asleep in his mother’s lap. When his turn finally came around, he awoke, stood and announced: “You would scarce expect one of my age, To speak in public on the stage. In coming years and thundering tones, The world shall hear of Sam P. Jones.” It was said that Sam Jones could name his price for candy around town as he would be asked over and over again to repeat his famous speech.

Four years later… his mother died. Sam Jones would learn, for the first time but certainly not the last, that a painful part of life is dealing with loss. The death angel had snatched his precious mother away and carried her out into eternity. Much later in life, this is how Sam Jones would describe his devasting childhood loss. “My mother was a kind, painstaking, sweet spirited Christian woman, but her gentle hand led me but a little ways. I was only nine years of age when I stood by her casket in the parlor at home and stooped over and kissed her cold lips in death. I shall never forget that hour. The saddest hour in any one’s life is the hour they kiss mother good-bye. She sleeps in the old cemetery of Oak Bowery, Ala.” “What is a home without a mother? No one can take her place. A boy never recovers from the loss of a kind, loving Christian mother.” Sam Jones would lose his younger sister, Mary Elizabeth, a year and a half after his mother’s death, dying two days after her seventh birthday.

Sam Jones and his siblings were sent to live with their grandmother Edwards for three years following the death of their mother in 1856. His grandmother exerted a wonderful influence upon Sam’s young mind. Sam’s wife Laura would later say that she was one of the holiest women that ever lived. She read the Bible through thirty-seven times on her knees. Her wonderful example of piety, prayerfulness and study of God’s Word made an abiding impression upon young Sam Jones.

John Jones would remarry Jane Skinner, known to the family as “Jenny” in 1859 and they would begin to put down roots in their new hometown of Cartersville, Georgia. In his adolescent years, while Sam’s father was away serving as a captain in Lee’s Army in Virginia during the Civil War, his absence left his children without very much parental supervision and without the daily guidance of a godly father. During those formable years, Sam had fallen in with a rough crowd of boys, strayed from his Christian upbringing and began to dabble with alcohol.

This is how Sam Jones described his first introduction to alcohol or ” liquid damnation,” as he frequently called it. “I can remember the first dram I ever drank. It made me feel manly. I thought, well, surely I have found the elixir of life, the grand panacea for all sad feelings. But I drank, and drank, until I despised myself, and loathed and loathed, and loathed my very being, because I was a miserable drunkard.“

Sam Jones was 15 when Sherman’s Army marched into Georgia making their march to the sea and he was once again sent to the home of his grandparents who lived on a farm in Kentucky. It was during his time in Kentucky, Sam Jones fell in love with Laura McElwain, the daughter of a prominent farmer. When the dust settled in the South after the Civil War, Sam returned home to a decimated Georgia to continue the good education that had started way back in his birthplace of Oak Bowery, Alabama. In June of 1867, he finished his high school education at Eurharlee High, where he graduated at the top of his class and gave the school’s valedictorian address.

Sam Jones didn’t attend college but chose to study law at home, following in the footsteps of his father John, who was himself a noted lawyer and successful businessman. In 1868, after only one year of studying law, he was admitted into the Georgia bar. Judge Milner, a local judge, told Sam’s father when he was licensed to practice law, “You have reared the brightest boy ever admitted into the Georgia bar.” A week later, he boarded a train for Kentucky and married Laura McElwain.

Sam and Laura’s life together in Georgia started out with great promise. Soon the couple would welcome their first-born child into their family, a beautiful baby girl given the beautiful name Beulah to match. Tragically, the infant child would have to drop her toys and grapple with the iron strength of death. She wouldn’t live to see her second birthday, taken from them at only twenty-one months. For the rest of his life, Sam Jones believed that the death of his first-born daughter had been the judgment of God upon him as a result of his drunkenness and waywardness. And he certainly felt that God could do it again.

To anesthetize the pain of the great loss, he once again began to consume alcohol. And in no time at all, alcohol began to consume him and he quickly became a full-blown alcoholic. Alcoholism would cause him to break the heart of his new Christian bride and would cause him to bring reproach and shame upon his family’s good name. The first four years of Sam’s marriage was marred by his alcoholism, which left him incapable of being able to successfully practice law. Years later, in a sermon Sam Jones reflected back on his youth: “When I was twenty-one years old, I was admitted to the bar to practice law in the courts of my county and State, and no boy in Georgia ever started out under brighter prospects than the man who is talking to you this afternoon. I was full of practice at the very first court that I was admitted to.” He went on to tell the audience, “But, boys, already I had begun to drink, and on and on for three long years I drank and drank. But, boys, in my awful hours of dissipation, I went on and on but with a devotion this world has never excelled my wife stood by me and spoke to me and loved me and prayed for me. But on and on I went.” What at first seemed to be a promising career in law was wrecked within two years by “practicing principally at the bar of the village saloon.” Alcohol robbed him of a successful law practice, shackled him to odd jobs such as working as a stoker in the Bartow ochre mines and running a stationary engine in order to feed his family. His dependence on the bottle dogged him like an imp from hell so that he could not maintain his job at the mines, and in utter desperation was regulated to a job, for fifty cents a day, driving a horse-drawn delivery wagon, on the streets of his hometown.

At the age of 25, Jones experienced a dramatic and remarkable conversion. The profound influence of his father contributed immensely to his decision to repent of his drunkenness and to become a new man in Christ. His mother died before she could make any permanent impression upon him but the appeals of his father, dying of tuberculosis, were more than he could resist. As Sam’s father lay on his deathbed, one by one he called each family member to his side to give them a parting word before he left this world. When he looked into the face of his second born son, being deeply troubled by his dissipation he lamented, “My poor, wicked, wayward, reckless boy, you have broken the heart of your sweet wife and brought me down in sorrow to my grave. Promise me, my boy, to meet me in heaven. “Under the deepest emotion, the son said: “Father, I’ll make the promise; I’ll quit–I’ll quit –I’ll quit!”

The next Sunday, Sam Jones went to Moore’s Chapel. His grandfather, Samuel G. Jones was a Methodist circuit rider and was preaching there that Sunday. He knew that his grandson was under deep conviction and he invited anyone who desired prayers of the congregation to come forward. Sam Jones responded. A few weeks later at Felton’s Chapel during the fourth verse of the invitation hymn, Sam Jones came forward to make a full surrender of himself to God and to join the church. Sam remembered: “And in that little country church, with my dear old grandfather preaching the sermon, I went and gave myself to God. I went forward and took his hand and looked up into his face and said, Grandfather, I’ll take this step today; I give myself, my heart, and my life, what is left of it, all to God and to his cause.” Three days later, he joined Felton’s Chapel during his grandfather’s revival meeting and he felt his call to the gospel ministry. His profession of faith came on Sunday and he preached his first sermon at New Hope Church on Wednesday. Jones later recounted the night that he preached his first sermon. When he and his grandfather arrived at church; Sam was told by his grandpa that the preacher that was scheduled to preach had written to him stating that he couldn’t make it to church and Sam’s grandfather was so hoarse that he couldn’t preach, therefore, it would have to fall to Sam Jones to preach the Wednesday night service. Jones said, “I took this text: “I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ: for it is the power of God unto salvation.” And I didn’t know but two things: first, that God was good; and the other, that I was happy; and that was my exegesis of that text,”God is good; I am happy.” Sam remembered that he talked for about twenty minutes that night and when he called for penitents to come forward, forty or more came to offer their hearts to God. “And when I got into the buggy with my old grandfather and we rode off, he said: “Go it, my boy! God has called you to preach.”

On November 27, 1872, less than three months after his call to preach, Sam Jones was admitted to the North Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, which assigned to him the poorest circuit in the state of Georgia, the Van Wert Circuit. Sam’s wife, Laura shared this account of his excitement in receiving his first charge. As Jones was leaving the conference, elated to have a place to preach, a fellow brother came up to shake his hand and asked, “Brother Jones, do you know what that circuit paid it’s pastor last year?” He replied, “No, I had not thought of that.” “Well,” said he, “it paid the preacher for his entire year’s work sixty-five dollars.” “Mr. Jones laughed and said: “I don’t care what they paid or didn’t pay, I have a place to preach now, and I’m going to it happy.” The Van Wert Circuit consisted of five rural churches and was located twenty-two miles from his hometown of Cartersville, in Polk County.

Years later, reflecting back, Sam Jones spoke of those hard times on his first circuit and how heavily in debt he was due to his alcoholism. “My whole assets were my wife, two little children, a bobtailed pony and eight dollars. These were my assets, and I owed about seven hundred dollars besides. I went on my circuit as poor as I could be. My stewards told me I looked like a clever young man, but I’d starve to death on my circuit.” When they arrived at Van Wert, the church did not even provide the Joneses with housing. Sam Jones would say later, “They wouldn’t even rent a house for me. I had to give my ten–dollar notes, one every month, toget a house to put my wife and little babies in. We had scarcely anything in the world. It was a sixty-five-dollar circuit. I stayed there three years, and no human being ever said I was preaching for money.”

Laura Jones stated, “The congregations increased wherever he preached. New life and zeal entered into the services, and the old circuit took on new life.” Those five rural churches, in three years, added five hundred people into its fellowship.

Due to the increase of people that were added to the churches and Sam Jones’ powerful persuasion to motivate folks to financially give, he wound up making $2100 dollars for his three-year tenure on the Van Wert Circuit. William McLoughlin observed, “It soon became apparent that Jones was no ordinary circuit preacher.” Sam Jones received his second appointment of eight churches in 1875 on the Desoto Circuit in Floyd County. It was during this tenure that he was to meet a preacher that had the greatest personal influence on his life as a mentor and father to him in the ministry, the Rev. Simon Peter Richardson. Sam Jones said of Rev. Richardson in his autobiography, “The great nuggets of truth thrown out by him in the pulpit and parlor, were food to me. He saw some great truths more clearly than any man I ever heard talk; he was a father and brother and teacher to me.” He then spent two years on the Newbern Circuit in Newton County serving five churches, and one year on the Monticello Circuit serving six churches in Jasper County. With no formal seminary training, Sam Jones read and studied the Bible with a degree of concentration comparable to that with which he had studied law. Jones recounted in his own testimony about his early days in the ministry and about the tremendous influence Charles Haddon Spurgeon, the Baptist preacher from England, had on him and how much insight he had received from his writings. He imitated much of Spurgeon’s style and considered him the grandest preacher of the nineteenth century. Jones stated that when he started out on his first circuit that he owned only three books, the Bible, the Fifth Volume of Spurgeon’s Sermons and an old book of skeletons of sermons. Jones’ Bible was his most treasured book but he read and reread the sermons of Spurgeon, “until my soul and nature was stirred with the spirit of the man.” Jones said that when he read his text from the Bible in preparing a sermon, he would ask himself, “If Spurgeon treated his text that way, how shall I treat mine? And much of the directness of my style I owe to Spurgeon, the grandest preacher of this nineteenth century.”

Laura Jones stated that her husband’s revival work started on the last circuit that he would serve as a pastor. “While on the Monticello work, Mr. Jones assisted more pastors in revival work than he had been able to do before.” A fellow pastor and friend of Jones, George R. Stuart said about his time as a pastor, “Eight years in this valuable experience gave him some of the richest lessons of life.” It can be well said of Sam Jones what was said about Jesus, “the common people heard him gladly.” He considered his greatest compliment, and the one that he appreciated the most, was that of a little boy on his first circuit. He was just finishing up the year’s work, and getting ready to go to conference. The little boy said to his father: “I want Brother Jones to come back to our church. I can understand everything that he preaches.” Sam’s wife said: “The gifts and graces of the evangelist were developed in him while a pastor.”There were two things that made him the great evangelist that he was. The first was his evangelical preaching. He took the Bible as his authority. He preached it just as he found it. In the second place, there must be an evangelistic spirit. A man may be evangelical in his preaching, and yet if he hasn’t the evangelistic spirit, it is out of the question to move men.”

One of the many tragic consequences of the American Civil War was the countless number of children that were left orphans. In 1869, four years after the conclusion of the Civil War, trying to alleviate the issue of orphaned children in Georgia, the Methodist Church had founded a home for orphaned children in Decatur, an area just outside of Atlanta. Dr. Jesse Boring proposed at the North Georgia Conference of the Methodist Church that it support an orphanage which might help alleviate the pain and suffering of the homeless child victims of the Civil War. The Decatur United Methodist Children’s Home was conceived in the post-Civil War era in response to the demand generated by the war.

Eleven years after its conception, financial support for the orphan’s home had begun to dry up and their arrears were in the “red”. Laura Jones states, “The Home was overwhelmingly in debt. It could hardly have been sold for enough money to have cancelled the indebtedness.”

During the eight years that Sam Jones had been a Methodist circuit riding pastor, he had made a reputation for himself in the Methodist conference for being a prolific fundraiser. For Sam Jones to be able to bring in seven hundred dollars a year, on a sixty-five-dollar a year circuit, demonstrated the tremendous ability that he had to motivate people to give financially to support the work of God through the local church.

In December of 1880 at the Methodist conference in Rome, GA, Bishop McTyeire asked Rev. Sam Jones to assume responsibility as Agent for the Decatur Orphan’s Home to save it from dissolution. “Jones was selected for this particular job, at least in part, because of his reputation as an outstanding fundraiser. He was, in fact, far more than a fundraiser. He was among the best-known Methodist evangelists in the country, certainly in the South.” In the fall of 1881, Jones was appointed agent of the Decatur Orphan’s Home and asked to use his rhetorical skills and his power of persuasion in soliciting funds to save the institution from financial ruin.

In 1883, for the first year since its inception, the Decatur Orphan’s Home was declared to be debt free. Sam Jones paid off all the debts which were twice as much as he had been initially told and raised enough money to erect the handsome main building, now known as the “Sam Jones Building.” The Atlanta Constitution ran an article in 1896, on the history of the Children’s Home commemorating its twenty-fifth anniversary which stated: “In 1880 Rev. Sam Jones was made agent of the home and at that time that he took charge of it, it was in debt to the amount of $10,000. By his hard work and ceaseless efforts, he succeeded in paying off the entire debt and erecting the present buildings. For ten years he supplied all the funds.

There came an unseen benefit of speaking and raising money to save the Decatur Orphan’s Home from financial ruin, it opened many doors in Methodist Churches for Sam Jones to preach in, doors that had previously been shut tight. Sam Jones stated: “The first revival work I did that gave me any notoriety in my own state, was in 1879 and 1880; then the calls to work in revival meetings multiplied upon me, and I soon found that I was giving half of my time to outside work.” As a result of his traveling and preaching, the newspapers began to take notice and write about the Revivalists from Georgia and his fame began to spread. Jones said later, that he accepted the appointment to the Decatur Orphan’s home “mainly because it gave me more tether line, and from then until now I have been almost constantly in revival work.”

In 1881, Sam Jones would have a fortuitous meeting with a Baptist pastor in Macon, Georgia. Dr. Lamar was strongly impressed with the Methodist preacher from Cartersville when Jones came to Macon. When Dr. Lamar accepted a call to a church in Memphis, Tennessee two years later, he would recommend Jones to a pastor’s conference meeting as the preacher that they should contact to conduct a great union revival in their city. As they discussed what preacher to invite and were at getting to their wit’s end, Dr. Lamar arose and said: “Why not get Sam Jones? “And immediately the question came up: “Who is Sam Jones?” Dr. Lamar said: “I referred you to Dr. S. A. Steele, or Dr. R. H. Mahon. Probably they can tell you about him, as he is a Methodist and a member of the North Georgia Conference.” The two Methodist ministers replied that they had never heard of Sam Jones. “Well,” said Dr. Lamar, “he is the most unique man, I ever saw. He is a sensation within himself. He can come nearer turning the city upside down than any man upon this continent. If you will get him and give him the middle of the road, he will stir up things. The only trouble will be to get a place big enough to hold the audience.”

Sam Jones said of this meeting and of his first notable newspaper coverage outside of his home state: “The first revival I ever held which gave me newspaper notoriety was in Memphis, Tenn., in January, 1883. Since then, I have worked in most of the States, and in some with marked success.” Soon after Mr. Jones’ meeting in Memphis Tenn., in 1884, Dr. Talmage was visiting in that city and heard of the remarkable work there. It was in January of 1885, when Mr. Jones held a month’s meeting in Brooklyn, N.Y., with Dr. T. Dewitt Talmage, in the famous Brooklyn Tabernacle. The Pennsylvania’s Canton Independent- Sentinel newspaper covering his rising fame said, “He has held a great many successful meetings, prominent among which were those at Talmage’s Brooklyn Tabernacle, January, a year ago; at Waco, Tex.; Memphis, Tenn.; Nashville, Tenn.; Plattsburg, Mo.; St. Joseph, Mo.; Birmingham, Ala.; Knoxville, Tenn.; St. Louis, Mo.; and Cincinnati.”

It was in 1885 that Sam Jones’ path in life would cross with a prominent business man in Nashville, Tennessee that would forever solidify his place in history. The city of Nashville was rapidly growing in population and although financially prospering, it was however, a city with many vices and a city that was on the verge of spiritual bankruptcy. Nashvillians became alarmed at such manifestations of social unrest as rising crime, public drunkenness, and pervasive poverty. Lower Broadway with its saloons, gambling, and prostitution was an affront to those moralists who were being swept along by the strong current of revivalism engulfing the nation. It was into this environment in 1885, that Sam Jones was invited to Nashville to hold a series of revival meetings. The Georgia Revivalist requested a building or tent that would seat at least three thousand, preferably five thousand. When the ministers balked at that suggestion and still not entirely convinced of the necessity of such a building, Jones compromised with them by making a date to spend one Sunday in Nashville in March. This would give the ministers the opportunity to hear the revivalist from Georgia and then determine if he could draw a crowd too large for the churches to hold. He preached in three churches and the immense crowds filled the churches to overflowing, and hundreds went away without getting sight of the preacher. After leaving Nashville, the newspapers had been discussing the sermons of Mr. Jones. One paper stated: “Nashville is still buzzing over the visit of this unique evangelist. In the daily newspapers he has been assailed and bitterly and defended warmly, and almost everywhere Sam Jones has been the principal topic of conversation, and still the stir continues.”

Sam Jones returned to Nashville in May, following the stir of sensationalism and publicity that he and the newspapers had created back in March. One of Nashville’s wealthiest and most prominent citizen in 1885 was Thomas Green Ryman. Tom Ryman was born in south Nashville on October 12, 1841. At an early age, when his family moved to Chattanooga, young Tom learned about the ways of river life by fishing with his father in the Tennessee River. The family moved back to Nashville in 1860 and Tom Ryman’s father died shortly thereafter, making him the sole provider for his mother, three sisters and brother.

During the Civil War, Tom had a successful fishing business selling to both Union and Confederate soldiers which enabled him to buy his first steamboat. By 1880 he had two packet companies operating on the Cumberland and lower Ohio Rivers, and in 1885 he consolidated these into the Ryman Line with a total fleet of some thirty-five steamers that traveled up and down the Cumberland River carrying old wine and new whiskey along with dancing girls that entertained in ornate gambling casinos. Ryman also owned a saloon on Broad Street, down by the wharf, where he sold cheap whiskey. As one account has it, Thomas G. Ryman was “a swinging soul who ran floating dens of iniquity” until the night “he and some boys roared into the tent meeting of an evangelist named Sam Jones.”

It would be a memorable day on May 10, 1885, that Ryman came to the tent meeting with some men with him to protect their business interests and to rough up Sam Jones and run him out of town. When Sam Jones was informed that some riverboat men had expressed an interest in assault, Jones announced that he welcomed exercise after the service. As the legend goes, Sam Jones had been tipped off prior, that the key to Tom Ryman was that he dearly loved his Christian mother, she was nearest and dearest thing to the man’s heart. Jones chose to preach a sermon that night about the sanctity of motherhood and the tremendous influence that a godly mother shadows over a little boy’s life.

After an hour and a half, Jones ended the sermon by extending the right hand of fellowship to any who might care to grasp it. Tom Ryman stumped forward, leaning heavily on his cane stating, “I came here for the purpose that Mr. Jones said, of whipping him, and he has whipped me with the Gospel of Christ.” Tom Ryman was radically saved from the errors of his ways, becoming a new convert to Christ and in doing so, becoming the biggest fan that Sam Jones ever had. He immediately did away with all of his liquor on the steamboats and the sins that accompanied them, and pledged to build Jones a building in Nashville that could accommodate the size of the crowds of people that he drew, vowing that Sam Jones would never have to preach in a tent in Nashville again. He would construct for Jones the beautiful, Union Gospel Tabernacle, that was named for a time, the Jones-Ryman Auditorium. However, upon the death of Tom Ryman in 1904, Sam Jones suggested as he eulogized his dear friend, that the name should be simply changed to the Ryman Auditorium.

After the death of Sam Jones at a memorial tribute for him in Nashville, Tennessee, Professor J. W. Brister, of Peabody College for Teachers, gave a brief address, stating, “Nashville owes him an incalculable debt. This splendid auditorium ought to be rechristened the Jones-Ryman Tabernacle; and on either side of the great organ, some day to be installed, ought to be placed a life size statue-one for Sam Jones, who inspired the building; the other of Tom Ryman, his follower.” “Jones considered Ryman the brightest jewel in his heavenly crown and would often say there has been no more wonderful convert to God in the nineteenth century than Tom Ryman, of Nashville.” McLoughlin states in his book about Sam Jones, “The campaign which first put Jones at the top of the profession was his Nashville revival in 1885. In this city of 50,000, it became obvious that Jones was taking revivalism on a new task. He was turning it into a combination of popular entertainment and civic reform.” Sam Jones in speaking of the Nashville meeting, always referred to it as “that memorable meeting.” To him, it was the greatest meeting that he ever conducted. A newspaper from McMinnville, Tennessee, a suburb of Nashville reported: “Excursion parties are going to Nashville from various parts of our State and from other States, to hear the great Georgia evangelist, Rev. Sam Jones. Three hundred persons were converted in one night this week under his preaching.” Sam Jones loved the city of Nashville and conducted eighteen revivals there alone. The same year that Jones converted Ryman to Christ in Nashville, he bought his wife and family a cottage on 224 West Cherokee Ave in his hometown. Tom Ryman, along with some other prominent citizens of Nashville made Jones a very generous offer to move his family and his ministry from Cartersville to Nashville.

The Sunny South Newspaper in Atlanta reported in an article on June 6, 1885, “Rev. Sam Jones captured Nashville, but the Nashville people could not capture him. They offered to give him a house and a lot worth $10,000 if he would agree to make their city his home. He replied that Mrs. Jones was very fond of her home in Cartersville, and he declined the kind offer with thanks.” They insisted that he keep the money, which Jones would use to pay off his creditors and furnish “Rose Lawn” in Victorian splendor. The Jones’ home was dedicated debt free on Christmas Day 1885, with Jones praying it would be “a place where God can come and feel at home,” a place with nothing “to grieve away his holy spirit.”

Sam Jones had an open-air Tabernacle built a few blocks from Rose Lawn, his Victorian home, where he held annual revival meetings. The revivals drew huge crowds that came by train to hear Cartersville’s favorite son, as well as other visiting preachers. The inscription on the Historical Marker at the site where the Sam Jones Tabernacle in Cartersville used to stand reads: “For twenty years thousands came annually to this site, attracted by the magnetic personality and forceful eloquence of Sam Jones.” It is obvious that the writer of the Walker County Messenger is taken with the fact of just how much everyone loves their famous hometown revivalist. The writer states, “It is said that a prophet is not without honor save in his own country. This cannot be applied to Sam Jones, for everybody in and around Cartersville loves him, and he is unquestionably, a wonderful man. Newspaper accounts of him and his sermons do not do him justice.” Although Jones traveled extensively as a revivalist, his wife recounts that he always loved Cartersville and cared about the local people’s interests. One of the greatest meetings ever held in Cartersville by Jones was in 1884, which resulted in eighteen saloons closing up shop due to the influence of their most famous citizen’s stance for prohibition.

In 1893, the Joneses bought a house in Marietta, Georgia to be closer to Atlanta. They had refused to move eight years earlier when Tom Ryman and a few other businessmen in Nashville made a generous offer to them to relocate to their city. Though they loved their hometown of Cartersville and had never considered moving away, they reasoned that if they lived closer to Atlanta, it would give Sam Jones easier access to a greater number of trains going to Atlanta, which would give him several more hours to spend at home. They had only told a few close friends about their plans to leave, however, before long word got out that the Joneses were moving to Marietta. Laura recalled, “When the news was spread abroad, one of the most beautiful events of our lives happened. Its influence was so great that we could but feel it’s power, and although we had purchased this beautiful residence, we disposed of it.” The day of their decision, a little after dark, Laura Jones answered the ring of the front doorbell. The front lawn and veranda were full of white people. About the same time, there was a noise at the back door and the back lawn and veranda were full of black people. Col. Warren Aiken, a gifted attorney and dear friend of the Joneses was chosen to be the spokesman for the white citizens. He spoke for about twenty minutes, telling the Joneses just how much they were loved and respected in their hometown and asking them to dismiss the notion of moving away. Then the spokesman for the black people stepped forward and with a voice full of emotion said: “We feel that you were the instrument in God’s hands in putting whiskey out of our town, and we believe that if you go away from here it will come back again, that we will not be strong enough to keep it out, and we beg of you, Mr. Jones, not to go away.”

Sam Jones’ influence was not only felt with the local citizens of his cherished home town but all across the nation, all the way to the highest office in the land. President Theodore Roosevelt stopped at the Fair Grounds in Atlanta in 1905 and asked the committee to bring Sam to the platform. President Roosevelt, grasping his hand, exclaimed, “Sam, you have been doing in a big way as a private citizen, what I have tried to do as a public servant.” Fifty thousand people echoed his comments with their applause.

A year later in October of 1906, Sam Jones was invited to Oklahoma to preach for several weeks. In later years. Laura rarely traveled with her husband, however, Sam really pressed her to make this trip with him. People in Oklahoma that had not seen Sam Jones in many years commented at just how much that he had aged since they had last seen him back East. On October 13, 1906, Sam Jones preached his final sermon entitled “Sudden Death”.

During that powerful message, he spoke of how he would like to die like his father did – with all of his children around his bedside. Sam Jones said, “I don’t know where or when or how I will die. I may fall in the pulpit; I can’t tell. I may die away from home; I can’t tell. When I go, I will go home to God as happy as any schoolboy ever went home from school.” The next day he boarded a train in Oklahoma City carrying him back home to Cartersville for a birthday celebration at Rose Lawn on October 16, 1906, which would have commemorated his 59th birthday.

After eating dinner one night, Sam Jones called the Pullman conductor over and said, “I saw a sick man and a tired wife in the day coach. Please have your porter bring them into the Pullman and give them a place to sleep. I will pay the fare. When they were checked up, Sam Jones handed him the money remarking, “They’ll have a good night’s rest and I’ll have something left over for them when we reach Memphis.” Walt Holcomb, the son in law of Sam Jones said he left Sam about 11:00 p.m., where Sam Jones was stroking the hand of the sick man saying, “I am so sorry you are so weak but I am glad we could give you this comfortable bed.” He turned to the man’s wife and said, “You look so tired. Lie down and rest and I will look after your husband.” She looked up into his face and smiled and said, “You have done more for us than anyone else. I could not let you do that.” Sam Jones said, “Well I am wondering if you have enough money to get home. Sometimes, when we are travelling, we run short of funds.” The woman broke into tears. She said, “My husband was dying of consumption and we stayed out west until we had spent all we had. He begged so hard to go home to die. We just had enough money to buy tickets to Memphis. I don’t know what we shall do when we get there.” Sam Jones said, “Well I’ll buy the tickets to get you home and give you money for your meals. Don’t let that worry you. Good night.” Walt Holcomb said, “These were the last words I heard Sam Jones speak.” The next morning Sam Jones got up and dressed about 6:30 a.m. Suffering from nausea, he called for a cup of hot water. While waiting for the water, suddenly he collapsed. His son in law Walt Holcomb said, “After his death I found some money in Sam’s pocket, and recalling his last words, he went to the couple and said, “I heard Sam speak of taking care of your transportation.” He gave her the money explaining that it was Sam’s money, not his, telling her he was finishing Sam’s last act of kindness. Walt Holcomb said, “At the train station in Memphis, I saw the couple entering a train homeward bound as the railroad workers transferred Sam Jones’ casket to the baggage car.” You may ask what he had left over. Here is what he had left over:

Matthew 25:35 KJV For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in: 36 Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me. 37 Then shall the righteous answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, and fed thee? or thirsty, and gave thee drink? 38 When saw we thee a stranger, and took thee in? or naked, and clothed thee? 39 Or when saw we thee sick, or in prison, and came unto thee? 40 And the King shall answer and say unto them, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me (Matthew 25:35-40). God had called him to his reward following a kindly deed done for a stranger.

Upon his death, Sam Jones’ body was brought back to his hometown by train and then on to Atlanta where he was given the rare and distinct honor of lying-in state in the Georgia Capitol for twenty-four hours. His wife said, “Standing by the side of his casket in the Capital of Georgia at Atlanta, I watched the thousands of people pass by” and she estimated that thirty thousand people came by to pay their final respects. She continues by adding, “And as they passed by, hurrying along, I looked at the great, the poor, the rich, the white, the colored, the little boy, the old man, the little girl, the old woman, the strong, the feeble, and as I saw them pass, they wiped the tears from their faces.”

Rev. A.W. Lamar stated, “The death of Rev. Sam P. Jones was a national loss.” The blow was felt nowhere more strongly than it was in his hometown of Cartersville, Georgia. Both the black and white citizens that had come thirteen years earlier to beg their most famous citizen not to move from his beautiful home and leave their city, came back to Rose Lawn once again, this time to pay their final respects. Sam’s widow described the touching scene: “In through the front door with the thousands of white friends, well from the rear came the hundreds of colored people who almost worshipped “Mars’ Sam,” and the two files met and passed at the casket at their beloved friend – stood uncovered and equal in the presence of the mighty dead.”At a memorial service conducted by J. Wilber Chapman he observed, “God not only gave him wide observation and a great experience, but he trained him through trial and suffering to be the man that he was.” During his lifetime, Jones saw himself as a soldier of the cross of the Lord Jesus Christ fighting a spiritual war against the evils of his time. He easily related to sinners because he was one, whom God had redeemed. His battle was with the devil, the enemy of God, and alcohol, the chief tool that the enemy had used in his attempt to destroy Jones. Jones fought this war with the greatest weapon God had given him, his astounding ability to communicate truth.

His lifelong battle cry was that most of the crimes in the United States were intertwined with alcohol and that crime would be immediately eradicated with the eradication of liquor. In speaking to audiences, Jones frequently recounted his own painful and shameful journey into dissipation lamenting, “How did I become a drunkard? By drinking wine like some of you do. If any man had tasted what I have and been where I have been, he’d be recreant if he did not preach as I do. I’m not only not going to drink but I’ll fight it to perdition, and when perdition freezes, then I’ll fight it on the ice.” His wife said, “From the very first time he ever opened his mouth as a minister of the gospel until the last sermon fell from his lips before going to heaven, there were very few sermons in which he did not preach directly against the traffic or by suggestion pearl his truth at this national evil.”

At his funeral, Bishop Ivan Lee Holt said, “A man who found two worlds so close together and God so near seemed to hundreds of baffled and confused humans as a good guide to follow.” Countless souls followed Jones, as he followed Christ, here in this life and followed him into the next life for all eternity. They buried his body at Oak Hill Cemetery in his beloved hometown of Cartersville, Georgia and the Scripture verse on his monument reads:

“And they that be wise shall shine as the brightness of the firmament; and they that turn many to righteousness as the stars forever and ever” (Daniel 12:3).

Sam Jones preached to a million people a year for twenty-five years during the last part of the 1800’s and the first six years of the 1900’s. “Someone has said that D.L. Moody reduced the population of hell by a million souls. Sam Jones on the fiftieth anniversary of his birth estimated that he had seen seven hundred thousand souls turned from the errors of their ways to a better life. He had nine more years to go before the sudden end. Figuring on the same basis, he saw more than a million souls turned to righteousness.” Sam Jones said, “the happiest moments of my life have been the moments when I have seen men’s souls given to Christ. The one earnest prayer of my life has been, God help me to help souls to Christ.”

Kathleen Minnix wrote, “Sam Jones did not deflect history as much as he reflected history. He is an important study for anyone seeking to understand the history of revivalism, the South, the prohibition movement, Methodist history, and American history as a whole.” And she ponders the most obvious and perfectly legitimate question, “Given the extent of his fame in 1906, it is surprising that Sam Jones went so quickly from death to obscurity.”

Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf told his Moravian Missionaries, “Preach the gospel, die and be forgotten.” Perhaps, Sam Jones wanted to serve the purpose of God in his generation, die and then be forgotten. Throughout his brief fifty-eight-year life, Sam Jones let his light shine for Jesus Christ and cast a long shadow for good over the countless lives of many in this great nation. His light for Christ continues to shine.

Following his death, a Methodist church in his hometown would be renamed in his honor. Rose Lawn, his beautiful Victorian Home, now stands as a museum, owned and operated by Bartow County and is referred to as, “The Crown Jewel of Cartersville”. Furthermore, every year thousands of tourists travel to Nashville, Tennessee to tour the Ryman Auditorium. Jones could have never imagined that when he died in 1906, the Tabernacle that his most famous convert and friend, Tom Ryman, built for him, in 1892, would one day become the home of the world-famous, Grand Ole Opry.

In coming years and in thundering tones, the world, once again, needs to hear of Sam P. Jones!

References:

Holcomb, Walt. Sam Jones: An Ambassador of the Almighty. Nashville, Tennessee: Parthenon Press, 1947.

Holcomb, Walt. Best Loved Sermons of Sam Jones. Nashville, Tennessee: Parthenon Press, 1950.

Holcomb, Walt. Popular Lectures of Sam P. Jones. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1909.

Jones, Laura. The Life and Sayings of Sam P. Jones. Atlanta, GA: Franklin-Turner CO. Publishers, 1907.

Eiland, William U. Nashville’s Mother Church: The History of the Ryman Auditorium. Old Hickory, Tennessee: Thomas-Parris Printing, 1992.

Stuart, George R. Famous Stories by Sam Jones: Reproduced in the Language in Which Sam Jones Uttered Them. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1908.

Stuart, George R. Methodist Evangelism. Nashville, Tennessee: Publishing House of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, 1923.

Stuart, George R. Sam P. Jones, the Preacher. Siloam Springs, Arkansas: International Federation Publishing Company, n.d.

The Sunny South Newspaper, Atlanta: June 6, 1885.

Sam Jones, Sam Jones’ Own Book (Cincinnati, Ohio: Cranston & Stowe, 1886).

Sermons (St. Louis: Barnett and Company, 1886).

“Jones Cartersville Meeting,” p. Page 6.

Sam Jones’ Late Sermons (Chicago: Rhodes and McClure Publishing Company, 1907

Cunyus, Lucy. History of Bartow County, Georgia. Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press, 1933.

Winkler, Gerald. Home Life. Milledgeville, Georgia: Boyd Publishing Company, 2001.

Minnix, Kathleen. “The Atlanta Revivals of Sam Jones: Evangelist of the New South.” Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South XXXIII, number1 (Spring 1989).

Minnix, Kathleen. Laughter in the Amen Corner. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1993.Laura Jones stated that her husband’s revival work started on the last circuit that he would serve as a pastor. “While on the Monticello work, Mr. Jones assisted more pastors in revival work than he had been able to do before.” A fellow pastor and friend of Jones, George R. Stuart said about his time as a pastor, “Eight years in this valuable experience gave him some of the richest lessons of life.” It can be well said of Sam Jones what was said about Jesus, “the common people heard him gladly.” He considered his greatest compliment, and the one that he appreciated the most, was that of a little boy on his first circuit. He was just finishing up the year’s work, and getting ready to go to conference. The little boy said to his father: “I want Brother Jones to come back to our church. I can understand everything that he preaches.” Sam’s wife said: “The gifts and graces of the evangelist were developed in him while a pastor.”There were two things that made him the great evangelist that he was. The first was his evangelical preaching. He took the Bible as his authority. He preached it just as he found it. In the second place, there must be an evangelistic spirit. A man may be evangelical in his preaching, and yet if he hasn’t the evangelistic spirit, it is out of the question to move men.