By Susan Gilmore

In 1993, Dicksie Orline Bradley Bandy was honored, posthumously, by the Georgia Women of Achievement (GWA). The GWA goal is to “honor the many inspirational and courageous female trailblazers” in Geogia. Dicksie is, to this day, the only woman listed with the GWA as a businesswoman. Her impact in North Georgia improved living conditions for many and transformed the area from mainly small farm agriculture to manufacturing.

Dicksie Bradley was born near Folsom, Bartow County, in 1890. Her father was Dr. Richard S. Bradley (Dr. Dick). Her mother, Ora Lewis Bradley, authored her and her husband’s biography, A Country Doctor’s Wife. Dicksie was named for her father, Dr. Dick.

Education was often not a priority for girls in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, Dicksie’s parents believed strongly that all their children should receive a good education. Dicksie attended Reinhart College and Georgia State College for Women from which she earned a teaching degree.

She taught in Bartow County, marrying Burl (B.J.) Bandy in 1915. She also worked as a telegraph operator for the railroad during WW 1. This gave her an unlimited lifetime pass to ride on the train.

In 1920, Dickie and her husband opened a country store in Sugar Valley, Georgia. The store was a success. They soon opened a second store in Hill City. But the post- WW1 agricultural recession in the mid 1920’s caused area farmers to be unable pay their debts. The stores owed $22,000 to suppliers. The Bandys refused bankruptcy and Dicksie sought other avenues of income.

Dicksie visited a local tufted bedspread maker named Catherine Evans Whitener. Catherine had adapted the colonial method of “candle-wicking”, by cutting the stitches to create tufts. She had a flourishing cottage industry with her brother selling spreads on the Dixie Highway. Catherine shared her knowledge and several patterns she had created with Dicksie so she could start her own bedspread business.

Dicksie began with the “Spread House” system for her first tufting company, B.J. Bandy Company in Sugar Valley. She operated her business using a network of local farm families to produce spreads.

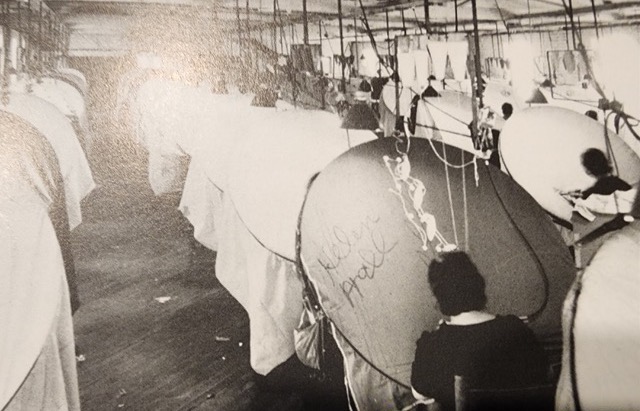

A “Spread House” was a small warehouse, home, or even chicken coop, where workers would stamp patterns on sheets of unbleached muslin. Men called “haulers” would deliver the stamped sheets and yarn to rural homes and women would tuft, using the patterns, the thread through the cloth. The children would cut the tufts. The hauler would collect the spreads and pay the “tufters” (or “turfers,” as they were sometimes called). Most “tufters” earned 10 cents per spread. The haulers returned the products to the “’Spread Houses” for finishing. Finishing involved washing the spreads in hot water to shrink them and to lock in the yarn tufts. The tufted spreads could also be dyed in a variety of colors. The spreads were hung on clotheslines to dry and beaten with brooms to get the tufts to stand up. A finished spread typically sold for $2.50.

Dicksie had several advantages over other women in the tufting business. She was well educated and was experienced with running a business. She knew the suppliers of the raw materials needed to produce a spread. Her husband had a line of credit with both the banks and suppliers. From her country stores’ customers, she knew who could tuft and which men needed work and could be haulers. She was willing to pay above the going rate per spread – 25 cent. Her total cost per spread was about $2.00.

Dicksie did not wish to compete with the others selling spreads on “spread lines” along the new Dixie Highway. She decided to go to the markets, in the north. Her husband, like the many others, did not believe her strategy would work and even told her she was “foolish for trying”.

Dicksie was not deterred. She packed her suitcase, with a completed bedspread, and used her railroad pass. She traveled to Woodward and Lothrop in Washington DC and asked to see the buyer. They bought 400 spreads at $4.00 each a 100% profit for the Bandys. She then traveled to Hotchschild and Kohns in Baltimore and sold 200 more. She had planned to go on to New York but realized she had more orders than she could fill. Dicksie returned to Georgia and hired dozens more tufters in Sugar Valley, Kingston, Calhoun, Adairsville, and Hill City and was able to fill all the orders.

Dickie then traveled to Macy’s in New York. She procured an order for 1,000 spreads. She knew she had to find a faster and more efficient way to produce spreads. She could no longer satisfy the market as a cottage industry. She went to Georgia Tech where she met with the Dean of Engineering. He assigned a graduate student to work with Dicksie. The young engineer modified a single needle (embroidery) commercial Singer machine so that it would tuft the thick yarn into unbleached muslin without tearing the fabric and added a knife to cut the loops.

Dicksie bought several commercial Singer sewing machines from a bankrupt tailoring business and hired a mechanic to modify them. She located a closed cotton mill in Dalton and invited the young engineer from Tech to come up and help lay out the new tufting mill. The mill opened in 1931, as the first tufting factory. The sewing machines allowed for more intricate designs and stitches that were closer together. The tufted lines looked somewhat like a caterpillar, so the name of the product was changed to chenille. The word Chenille is taken from the French word for “caterpillar”.

The Bandy’s tufting mill brought greater productivity and control over the work process, and a steady income to the women and men who had formerly been paid for “piece work”.

Others saw the success of the Bandys and opened mills of their own. There were over 200 different tufting mills and spread houses in north Georgia during the 1930’s and 1940’s. The Bandys were successful because they invested in new machinery, new methods, and new technology. Tufting Machines quickly developed into four, then eight, then twenty-four needles. They were the earliest to use electric needle-punch guns. The needle-punch gun was later adapted for use in custom-designed area rugs. The carpet industry was founded on the manufacturing principles developed by Dicksie and her associates.

This new technology allowed the Bandy mills to produce more elaborate patterns and greater color variations than others in the industry. The Bandy Mills were famous for their high quality work. One of their bedspreads graced Scarlett O’Hara’s bed in the movie “Gone With The Wind”.

By the 1930’s, the Bandys had become the first millionaires in Dalton. Dicksie could afford to hire managers to run the mills and salesmen. The industry changed from women running the tufting business to men.

In addition to the Dalton mill, the Bandys opened J & C Bedspreads Co. in Ellijay and Southern Craft in Rome. They opened Bartow Textiles in Cartersville in 1940. It was the largest tufting mill in the country. It produced several chenille products: robes, small rugs, spreads, dolls, swimming capes, bathroom toilet covers, and draperies. Unique at the time, they had their own laundry facilities for finishing.

Dicksie and her husband would travel from Dalton every few weeks to check on the mill. While in Cartersville they stayed in the Hotel Braban which they co-owned with Dicksie’s brother. The name Braban comes from Bradley and Bandy.

The spread businesses continued to prosper after World War II. People were eager for color and beauty in their new homes.

In 1948, B.J., Dicksie’s husband, died. Their smaller companies were sold. The larger mills were divided between their children. Dicksie’s daughter, also named Dicksie, and her husband David Tillman inherited Bartow Textiles. David worked with DuPont to develop a method to apply a backing to rugs to prevent skedding and sliding. He also experimented with producing broadloom large area rugs /carpeting. The Tillman’s managed the mill until 1954. Tufted bedspreads were becoming less popular, and the new tread was for large area rugs. The Tillman chose to move on to other businesses.

Dicksie believed that carpet would be the next step in the tufting industry. The housing industry was taking off and many people were looking to cover their floors. In 1954, Dicksie convinced her youngest son, Jack Bandy, along with Bud Serelan and Guy Tenley, to invest in a Carpet mill. Coronet Carpet was created. The carpet mill opened using 12- and 15-foot-wide machines that used wool yarn instead of cotton. In 1960, the mill transitioned to use synthetic fibers – nylon and even larger machines. Coronet Carpets was the first carpet manufacturer to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

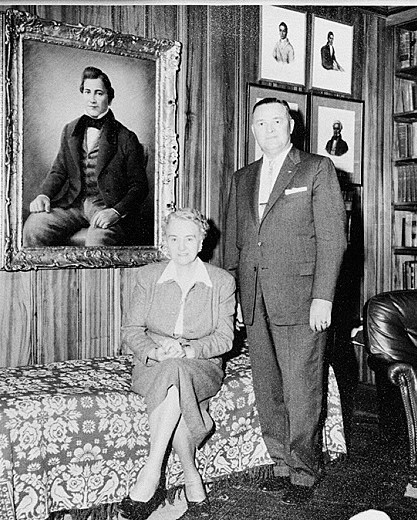

As she grew older and her involvement in business decreased, Dicksie began working on a project to recognize the 150-year history of the state of Georgia’s mistreatment of the Cherokee in North Georgia. She initiated and led the campaign to restore a prominent monument of the Cherokee Nation, the home of Chief Joseph Vann. Her project was the first restoration project coordinated with the newly formed Georgia Historical Commission. Through her work, she was named by the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, as their official Ambassador. In 1958, the restored Vann House was dedicated and presented to the State as a monument to Cherokee culture.

“My heart is filled with sadness when I think of the atrocities perpetrated on the Cherokees … I apologize to you, the Cherokee Nation, for what our gold-hungry, land-famished ancestors did.”

– Dicksie Bradley Bandy

Dicksie passed away in 1971 at the age of 81 years old.

“For her energy and skill in initiating the industrial recovery of Northwest Georgia and for her social conscience in trying to atone for the sins of the fathers, we honor Dicksie Bradley Bandy as a Georgia Woman of Achievement.” – Georgia Women of Achievement Dedication Ceremony

BIBLIOGRAPHY OR REFERENCES

https://www.georgiawomen.org/dicksie-bradley-bandy https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/41856292/dicksie-o-bandy

A Country Doctor’s Wife, 1940, Bradley, Ora Lewis