By Joel M. Sneed

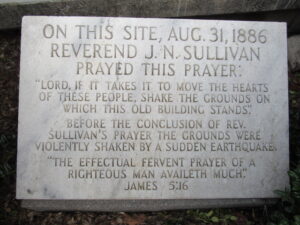

It was a typically hot August night, Tuesday the 31st, in 1886. In the small town of Pine Log, Georgia, worshippers had been listening to the preaching of Rev. J.N. Sullivan at the Pine Log Methodist Church. The air was thick, everyone tired as the evening wore on, and the Rev. Sullivan was apparently disappointed in the lack of response to his sermons during this week of revival. In his frustration he fell to his knees and cried out to the Almighty, “Lord, if it takes it to move the hearts of these people, shake the grounds on which this old building stands.”

It was a typically hot August night, Tuesday the 31st, in 1886. In the small town of Pine Log, Georgia, worshippers had been listening to the preaching of Rev. J.N. Sullivan at the Pine Log Methodist Church. The air was thick, everyone tired as the evening wore on, and the Rev. Sullivan was apparently disappointed in the lack of response to his sermons during this week of revival. In his frustration he fell to his knees and cried out to the Almighty, “Lord, if it takes it to move the hearts of these people, shake the grounds on which this old building stands.”

As he was uttering his prayer, the grounds of the church were suddenly shaken. The building shook perceptively. People were understandably terrified and many rushed to the altar to pray. Some dashed out of the church to spread the word about what had just transpired. Many stayed in the church throughout the night, praying. Religious fervor like never before was evidenced among the populace, with both attendance and contributions increased.

In Cartersville a similar occurrence was reported in The Cartersville Courant (pg. 2, col. 2) of September 2nd: “A meeting was in progress at the colored Baptist church. The meeting of the colored folks had progressed some time and the preacher did not perceive any interest being felt by his hearers. He finally prayed to Almighty God to prevail and do something to show the derelict audience that there was some supreme power. He made a most earnest plea that a sign of some sort be made to convince them of that fact. The prayer had hardly left his lips before the windows of the building began to rattle and the house to roll. The preacher led the hosts out of the building instanter, some falling out of the windows. In the jam many persons were slightly hurt and one boy had an arm broken. One old colored woman jumped out of a window and succeeded in bruising herself up considerately and cutting a deep gash over her forehead.”

In Cartersville a similar occurrence was reported in The Cartersville Courant (pg. 2, col. 2) of September 2nd: “A meeting was in progress at the colored Baptist church. The meeting of the colored folks had progressed some time and the preacher did not perceive any interest being felt by his hearers. He finally prayed to Almighty God to prevail and do something to show the derelict audience that there was some supreme power. He made a most earnest plea that a sign of some sort be made to convince them of that fact. The prayer had hardly left his lips before the windows of the building began to rattle and the house to roll. The preacher led the hosts out of the building instanter, some falling out of the windows. In the jam many persons were slightly hurt and one boy had an arm broken. One old colored woman jumped out of a window and succeeded in bruising herself up considerately and cutting a deep gash over her forehead.”

Center of the Shaking

Simultaneous with these events, a large earthquake, centered near Charleston, South Carolina, was triggered. Striking at 9:51 P.M., the earthquake caused tremendous damage and loss of life in Charleston and the surrounding area. The estimated strength of the quake has been calculated to have been 6.9 to 7.3 on the Richter scale, that measurement scale not known at the time. Some 100 deaths were recorded in Charleston alone from the quake, which was one of the most damaging ever in the East Coast of the U.S. and which had been felt over more than half of the country. About 2000 buildings in Charleston were either damaged or destroyed.

This, then, was the cause of the shaking at the Bartow County churches that happened concurrently with two preachers invoking the power of God. Even after the cause was realized, it is said that the people of the area remained in their “readjusted” faith in the Almighty, and demonstrated that by a more faithful church attendance and giving.

Shock Waves Felt Close to Home

Damage from the earthquake was noted in many cities and towns in the Southeast. In Georgia, reports were made of damage in Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, Covington, and Canton. In addition to the happenings at the two churches noted above, Bartow County had its share of stories related to the quake, with The Cartersville American (pg. 3, col.1) of September 8th reporting that “somebody claims to have felt an earthquake shock nearly every night during the past week.” The same issue of the paper related an incident with one person in Kingston: “Our quiet little burg was considerably shook up on Tuesday night the 31st. Squire Burrough had retired and was dozing. His house is near the colored Methodist church, and when his house began to shake and tremble he jumped up and run and opened the door and Rev. Watson quoted his text in a strong voice. ‘Awake thou that sleepest and arise from the dead.’ Squire said he began to feel alarmed, and for a while he could not take in the situation.”

Alice Butler “Topsi” Howard relates in her book, Sunsets, Dooryards, and Sprinkled Streets, about damage to one large home in the north of the County. “Thistledale”, also known as the Hamilton House, was built around 1850 by Charles H. Hamilton. Hamilton had fought in the Mexican War and at one point had been captured and retained in the home of Gen. Santa Anna. While there, Hamilton admired the home, made a plan of the house, and later reproduced the home for himself just north of Adairsville. The walls were 18” thick and made of brick, and Howard relates how the Charleston earthquake had caused large cracks to form in the walls.

Back in Cartersville and vicinity, “much consternation prevailed among the people, in many instances whole families, slightly clad, congregated in the middle of the streets. The darkies generally were uncontrollable and participated in considerable yelling and praying. For some time after the shock a great hullabaloo was kept up by the darkies and they all thought the world was coming to an end. In many instances their condition was indeed pitiable.

“Our people were never more horror-struck and men that were never known to pray fell to their knees and began invoking the blessing of the Lord. It certainly was an awful time and well calculated to bring a person to the consideration of the serious side of life.” (Cartersville Courant, ibid.)

Other Local Evidence of Quakes

While the Charleston quake of 1886 is by far the better known of quakes in the Southeast due to the damage wrought over such a large area, other tremors have been felt on occasion, both before and after, but little damage was noted and therefore little record is extant. One familiar to this writer, of an unknown date, produced destruction of a natural feature in the north of the County.

A tributary of Oothkalooga Creek, Trimble Branch is a small stream emanating from the base of a hill amidst a jumble of large rocks. Such was not always the case, as this jumble of rocks was once a large archway over a passage that led into the hill. Native Americans were familiar with this lovely sight, chert flakes and Middle Woodland points having been found adjacent to the branch. More recently, local residents were known to have canoed into the passage for a short distance, reporting two large rooms before the waterway “sumped”, the roof coming down to the water’s surface and preventing further traverse.

In an interview of April 10, 1986 by this writer, Mrs. Elizabeth Trimble Hartley related that her father, George Layton Trimble, grew watercress in the pond there in the 1920s and 1930s, selling it to “fine hotels” in the North. The watercress was packed in barrels and stored in his ice house. She stated that in the late 1800s her father, as a boy, would go into the opening in a small canoe, and as a little girl years later she would throw rocks into the entrance and listen to the echo as the water ripples hit the walls inside.

It is not known when the arch fell, but certainly it was after the 1930s when watercress was cultivated there. Mrs. Hartley had no knowledge of when that would have occurred. This writer would be pleased to receive any information that could shed light on this issue.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OR REFERENCES Marble Marker at Pine Log Methodist Church, August 31 1836 Hundreds Return Each Year During August to Pine Log Methodist Campgrounds, (ND) Dixie Co-Op News Interview, Elizabeth Trimble Hartley, April 10, 1986