Joel M. Sneed

Joel Sneed at Tate Cave entrance

Etowah Valley Historical Society member Sam Graham, with an interest in anything pertaining to the history of the county, became aware of another possible name for Jolley Cave, the name used by cave explorers and as listed in the files of the Georgia Speleological Survey. In Civil War-era records a cave in Bartow County was referred to as Ravenel Cave, yet there is some uncertainty as to whether Jolley Cave and Ravenel Cave is actually the same cave. To help unravel this mystery Sam contacted Joel M. Sneed, author of Bartow County Caves: History Underground in North Georgia.

Sneed, a caver and also a member of the EVHS, had himself sought to learn more about the cave in 1981 in a visit to the holdings in the Georgia Archives. Here were located the John Riley Hopkins Family Papers, 1840-1915. Hopkins (1835-1909), a citizen of Gwinnett County at the time, was a miner who worked at several saltpeter caves. Among these was a Ravenel Cave, Bartow County, Georgia where he worked during June, July, and early August of 1862 and kept a journal of the mining activity there.

us, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

John Riley Hopkins

Caver and historian, the late Marion O. Smith, in an article in The Journal of Spelean History (Smith, 1988), relates possible saltpeter mining activity at Jolley Cave but makes the statement, “why the Nitre Bureau used the name Ravenel for today’s Jolley (sometimes Murchison’s) Cave has never been determined.” He continues by stating that “no one of that name before the Civil War had a direct tie to Cass or Bartow County.” Graham has located proof that such was not the case.

Graham, in searching property records for the county, learned that a Trust established for one Harriett Horry Ravenel of Charleston, South Carolina, had purchased the land lot wherein Jolley Cave is located, along with several other properties, from G. W. Glenn on December 17, 1852. The Trust owned this property until it was sold to Duncan Murchison in 1881. So, if Jolley Cave was, in fact, the cave that was mined by the Confederates for saltpeter, referring to it as Ravenel Cave would have been appropriate. However, the Confederate Nitre Bureau generally shied away from using a property owner’s name and this was likely the reason that Smith hadn’t searched property records for a Ravenel. But, was this actually the cave?

In his article on the Ravenel Cave Confederate Nitre Works, Smith makes reference to a Union map that shows a “Potash Works” that he states “matches almost exactly” with the location of Jolley Cave, and then follows with the proclamation that “it is concluded that Jolley is the Confederates’ Ravenel Cave.” Another, more detailed map that Graham has located, this one a Rebel map, shows more accurately the location of the potash works, even delineating six kettles in use there. Jolley Cave is over a half-mile from the location shown for the potash works. Both of these maps are from 1864.The cave was mined in 1862 and the potash works may not have even been in use at that time. But there is a bigger problem with using the site of a potash works as justification for Jolley Cave being Ravenel Cave.

While potash is required in the saltpeter process it has other uses and the location on a map of a potash works does not mean that there is a location of nitre dirt there, cave or otherwise. In fact, no known cave that was mined for saltpeter has been denoted as a “potash works.” Ralph W. Donnelly, in “The Bartow County Confederate Saltpeter Works,” states that “the production of the potash became a special and separate operation of its own, and the potash in the Confederacy was usually produced at one point and shipped to the saltpeter caves for processing the cave dirt.” He further states that the locations of the caves did not necessarily coincide with the locations of the most suitable wood for the production of potash.” (Donnelly, 1970)

If the mining did, in fact, take place in Jolley Cave its location on a very steep slope above the Etowah River would have created a tremendous amount of work for the laborers at the cave. Excavated dirt would have to be transported by wheelbarrow a rather long distance to a point that was flat enough to facilitate the processing and to be near the river for the requisite water. The use of a chute to move the earth down to the base of the slope, as was done at Trout Cave, West Virginia, for example, would not have been practical here as the slope ends right at water’s edge with no space there for processing. Besides this fact, Jolley Cave has none of the usual earmarkings of a nitre cave, such as dig marks, as noted by various speleohistorians who have visited the cave.

Smith offers up some other reasons that Jolley Cave could be the elusive Ravenel, but all of them could equally pertain to another nearby cave that has not been known to the caving community until recently, Tate Cave.

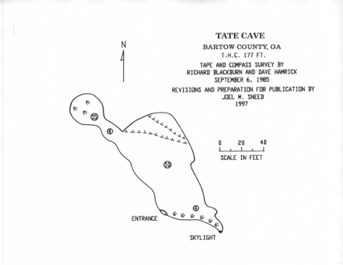

At the request of Sneed when he was studying caves in Bartow County, cavers Dave Hamrick and Richard Blackburn mapped a cave on September 6, 1985. The mappers were supposedly following directions to a cave known as Ned’s Cooler but they inadvertently came to a different cave yet didn’t know it. The map for that cave became labeled as Ned’s Cooler, and appeared in Sneed’s book with that name.

In 2007, J.B. Tate took Joel and Sharon Sneed to a cave, which Joel thought was Ned’s Cooler, and he entered it briefly. This was the cave that had been mapped in 1985 but has recently been shown to not be Ned’s Cooler. This cave has now been given the name Tate Cave and reported to the Georgia Speleological Survey. The cave is presently on property owned by Barnsley Gardens, and at the time of the Civil War it was owned by one Oliver H. Prince, apparently an absentee landowner, on the land lot adjoining the Spring Bank property on the north.

The home known as Spring Bank was built in the late 1830s by Charles Wallace Howard (1811-1876) who had come to northwest Georgia on a geological survey. In 1850 Howard discovered a natural, high-quality “cement rock” on his property. The rock was analyzed by the chemist Dr. St. Julien Ravenel (1819-1882) of Charleston, South Carolina, and deemed to be of a very high quality. Howard had likely first come to know St. Julien Ravenel, who was of Huguenot ancestry, when he was called to Charleston to reorganize the old Huguenot church in 1845. Howard served there as rector until 1850. In 1851 manufacturing of the material was begun under the name Howard Hydraulic Cement by Howard and his son. One of the first uses made of it was in 1852 on the exterior of the home of St. Julien Ravenel in Charleston, the high quality of this material being extolled in the Savannah Morning News of July 9, 1875. Ravenel was himself involved in the lime industry, co-founding a lime works in Charleston and supplying most of the lime used by the South during the Civil War. A close relationship formed between Ravenel and Howard linking Ravenel with Cass (later Bartow) County.

Julien Ravenel

St. Julien Ravenel

Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War on April 12, 1861, Howard wrote a letter on May 15 to the editors of the Southern Confederacy about the saltpeter operation in a cave south of Kingston perhaps being a good location for the mining of saltpeter by the Confederacy. That cave, which today is known as Kingston Saltpeter Cave, was seized by the government on June 14, 1862, renamed from Hardin’s Cave to Bartow Cave, and the works expanded, the cave becoming very important to the Confederacy. With Howard’s interest in the making of gunpowder, and the mining of nitrates to facilitate that as shown by this letter in 1861, it makes sense that he would be looking for possibilities of mining in other caves. How natural, then, that he would examine a cave near his own property.

According to Cunyus (1933), at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 Howard immediately entered service as a Captain in the Confederate army, and remained in its service until he was paroled in May, 1865. However, the unit in which he served, the 63d Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, wasn’t formed until October of 1862, so it is assumed that he didn’t go on active duty until then and was likely around Spring Bank at the time the mining would have taken place.

As at many nitrate mining caves, at the start of the Civil War as well as other wars, the caves were already providing nitrates for gunpowder on a small scale, for use by the property owner and perhaps for sale. By 1862 the price for saltpeter had gone from eighty-three cents per pound to three dollars per pound. The Nitre Bureau of the Confederacy was created in April, 1862, and when the government made a plea for identification of sources of nitre, the small cave just north of Spring Bank, whether nitrates were already being mined there or not, may have answered to that plea. A test of the material would likely have been required, and what better person to do this than the chemist St. Julien Ravenel. The cave referred to by the Confederate miners as Ravenel Cave was operational in June through early August of that year, per surviving payrolls and the diary of Hopkins, so the timeline would support Tate Cave possibly being that cave.

As stated by Smith (1988), the journal of miner John Riley Hopkins, which gives the name Ravenel Cave, is invaluable for providing information relative to the operation there. He states names of miners, activities in which he was involved day-by-day, and daily amounts of nitre produced. But overlooked by both Smith and Sneed was a sketch on the upper left corner of his first journal entry for Ravenel Cave (page 146). When rotated for a proper, north-upward perspective, this sketch matches with incredible accuracy the surveyed map of the cave produced in 1985 by Blackburn and Hamrick. Smith had never been to Tate Cave and would not have recognized the sketch as being that cave.

Tate Cave is situated quite well for a mining operation, albeit a small one. The land around the cave is quite flat, which would provide a good area for the vats, kettles and housing required. Water for the operation would have been obtained from Connesena Creek, some one hundred yards distant. The facilities could have been located next to the cave or anywhere between that point and the creek to best accommodate the retrieval of water. Since Hopkins had specifically noted that on some days he was working at “the water works”, it can be assumed that the main part of the operation was not located right at the creek. The cave was worked only for a few weeks, probably due to the limited amount of sediment in it, producing 310 pounds of nitre.

It is this writer’s feeling that the evidence provided shows that the cave known to the Confederate miners as Ravenel Cave was, indeed, the one known today as Tate Cave. As for the name of the cave, there are several reasons why it came to be known by the Confederate miners as Ravenel Cave. First, if St. Julien Ravenel was the one who had tested the deposit there, his name was certainly associated with the cave; his name may have been the only one on his report to the Nitre Bureau. Secondly, Ravenel had become quite established in the community. His relationship with Charles Wallace Howard has already been shown. He was involved with the mining activity at Cement, adjacent to Spring Bank. A trust established for his wife owned property not too far away, purchased from a local resident and farmer, Duncan Murchison. Some materials for the mining operation, and even some labor, were acquired through Murchison. And a friendship evidently developed there such that Murchison’s son would name his first-born son after St. Julien Ravenel in 1895. Additionally, Ravenel had an interest in nitre production, establishing in 1862 the Cooper River Works in Charleston for the production of that material (Yorkville Enquirer, 11/19/1862).

I want to thank Sam Graham for being the impetus for this current work which has caused this writer to untangle the identifications of two caves. He has worked tirelessly in searching old records for this article, including much about the connection of Ravenel to the county. Sam is an incredible researcher. I wish as well to acknowledge the assistance of EVHS member Gary Boston as well as Larry O. Blair, caver and historian. Additionally, we are thankful to J.B. Tate, for whom a historically-important cave in Bartow County is now named.

REFERENCES

Cunyus, Lucy Josephine, 1933. The History of Bartow County, Georgia: Formerly Cass. Southern Historical Press, Easley, S.C.

Donnelly, Ralph W., 1970. The Bartow County Confederate Saltpeter Works. The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 54(3): 305-319.

Smith, Marion O., 1988, Ravenel Cave Confederate Nitre Works and its Laborers. The Journal of Spelean History, 22(4): 14-25.

Sneed, Joel M., 2007, Bartow County Caves: History Underground in North Georgia. Flowery Branch, Georgia.