By Joe F. Head

A sincere word of gratitude is extended to Mr. Stan Bearden for his civic mindedness to help bring these finds to the attention of the Etowah Valley Historical Society in the spirit of historic preservation

Following the discovery of gold in north Georgia and the 1838 removal of the Cherokee Nation to Indian Territory in Tahlequah, Oklahoma the rush to extract precious ores was on in Bartow County.

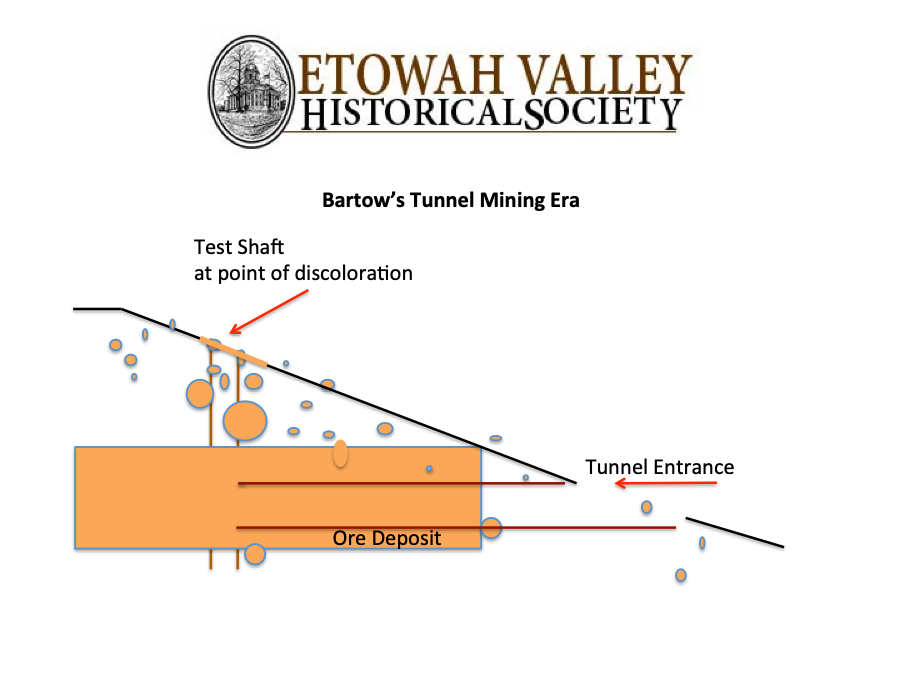

Early miners learned to recognize surface features such as color differences and topical weathered ores exposed on the ground. Miners began by panning for gold on creek banks and moved to digging vertical test well shafts in areas where surface signs indicated other ores waited for harvest.

Once a location revealed sufficient evidence miners moved down slope and dug a horizontal shaft into a hillside to reach the vertical test well and ore deposit. As the ore tunnel was excavated, in some cases, timbers were installed to support the sides and ceiling. These mining tunnels were labor intensive being hand dug using picks and shovels with dirt and ore being removed by wrangling wheelbarrows, buckets and rail carts.

According to Mr. Stan Bearden, New Riverside Ochre’s VP for Operations and Geologist a series of forgotten tunnel mines have been unearthed as a result of modern open pit mining practices. Improved mining machinery and detection technology has led the industry to return to former fields that were abandoned a century ago. An unexpected result is the discovery of forgotten tunnels and artifacts.

Salt Peter Cave

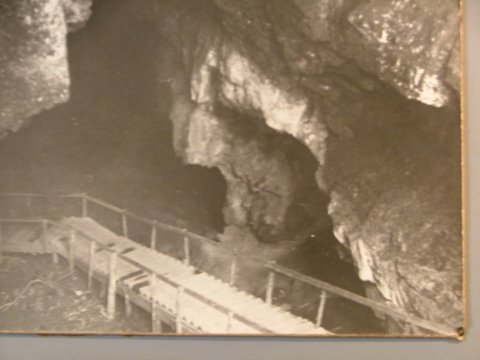

Located near Kingston on the south side of Highway 411 before Hardin Bridge Road is a natural geological feature once rich with nitrate and sulfur. Prior to the Europeans arriving to Bartow County, Native Americans used this natural cave for shelter, burials and mining. Caverns were enlarged as dirt was removed. The site was mined in the 1860’s for nitrates to make gun powder. When the Civil War broke out productivity became urgent and the Confederacy took over the operations. Once Union forces entered Bartow County in 1864, General Sherman ordered troops to take over the site and shut it down. Later the cave was used for moonshining and in the 1930’s as a cool environment for parties. Locals built a set of wooden stairs down to the large cavern and floored the room. Many personal initials and names have been inscribed on the walls from the 1930’s and 50’s. The property is now owned by a private foundation.

As modern mining operations returned to former ore sites and pit excavations were begun, often abandoned and forgotten tunnel shafts or vent wells were uncovered.

Depending upon the size and quality of the ore deposit the tunnel was often large enough to accommodate a man walking upright because the earth is considered “competent” to support shaft mining. If the quantity of the ore was in great supply a rail system was installed with carts to transport the raw ore from the source. These carts were often heavy – duty wooden or metal boxes with iron frames and wheels that rolled on narrow gauge mining rails. Carts were pushed out by hand or pulled by mules.

The nation’s first gold rush occurred in Lumpkin County Georgia and ignited a frenzy to remove the Indians, own land and prospect for gold. The miners followed the vein southwest leading into Bartow County and tracked mostly down Stamp Creek and Allatoona Creek. As gold miners exhausted the thinning gold they quickly discovered that Cass County held a rich supply of diverse minerals and ores, particularly iron ore, manganese, barite, ochre, graphite and bauxite.

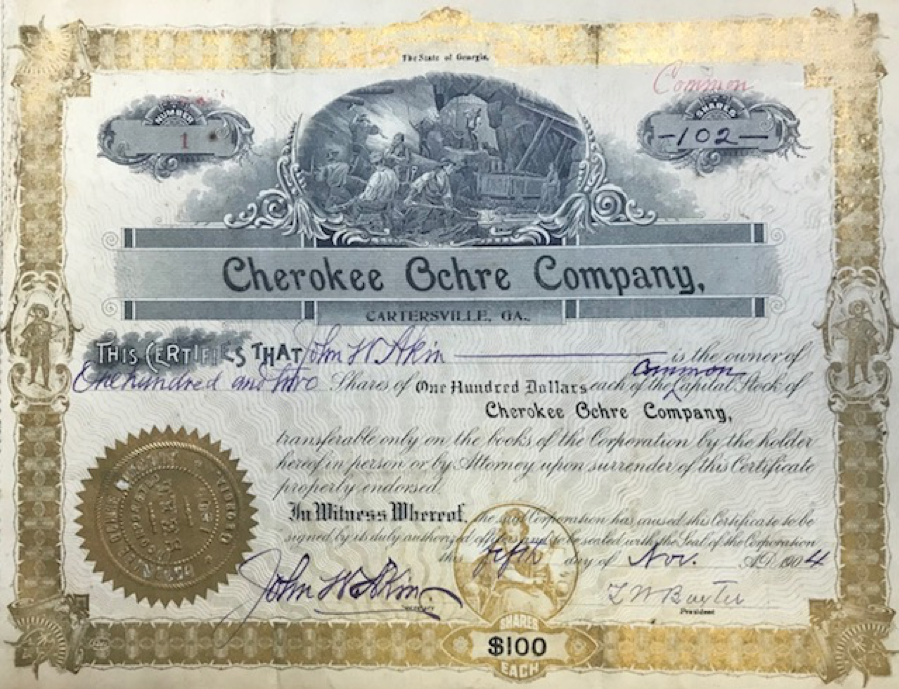

Tunnel mining was first conducted by private individuals and families. However the early corporate companies that established tunnel mining included; American Ochre Company, Blue Ridge Ochre Company, New Riverside Ochre Company, Georgia Peruvian Ochre Company and Standard Ochre Company. Companies sold stock in their ventures to raise capital in order to fund operations, purchase land, buy equipment and pay employees.

An earlier study conducted by Stacy Lusk, Kennesaw State Intern, it was determined that as many as 140 incorporated and chartered mining companies operated in Bartow between 1840 and 1950.

Following a century of Bartow mining the “last man standing” is New Riverside Ocher (NRO). New Riverside Ochre was originally founded in the late 1800’s as Riverside Ochre under the Satterfield family and following a devastating fire continues operations as of this date as NRO. Since 1877, Bartow has been mined by more than 10 ochre companies and has produced more than 1.6 million tons of pigment as of 2018.

As the demand for ores flexed and waned, NRO has found the need to return to former ore fields to locate remote deposits missed by early operations due to inadequate exploration and extraction technology. When deposits were discovered modern equipment was moved to the site to extract ore using open pit mining methods.

This practice has yielded fresh supplies of ore and has begun to reveal multiple instances of traditional tunnel mining sites that have long been forgotten.

NRO has uncovered several sites among others in land lots 387 and 390. Today these land lots are now occupied by the new Kroger shopping complex, Star Bucks and Avalon Apartments along East Main Street to the McDonalds at I-75 and follows I-75 south to where Old River Road runs below the interstate west toward the Old Dixie Highway 293 at the NRO headquarters. These sites were discovered as modern day open pit mining opened up large expanses of ground.

The image above reveals evidence of the many early tunnel mines that once existed in Bartow County prior to pit mining. NRO’s exploration proved the presence of deeper ochre missed by earlier mining and was reopened in early 1990. As the earth was removed from the surface a cross section of vertical timbers were uncovered and can be seen still embedded in the bank on the standing side of the open pit wall. This mine was previously owned by the Cherokee Ochre Company and was in operation prior to 1920. The tunnel was used to extract ochre and later the property was acquired by NRO. Once NRO returned to the site to begin open pit mining it was re-named the Bobbie Mine and in the process unearthed the old tunnel shaft remains. Here several artifacts were found including timber construction, carbide lamp filaments, narrow gauge cart rails and beverage bottles. The site is now covered by the Kroger store in land lot 406.

As technology improved tunnel mining was replaced with surface mining by using the open pit method excavated by large earth moving equipment to involve excavators, super dump trucks, massive draglines and pans. Matt Holton is seen below working the Big White Center open pit mine. It is not uncommon to find abandoned equipment in the field once it served its purpose.

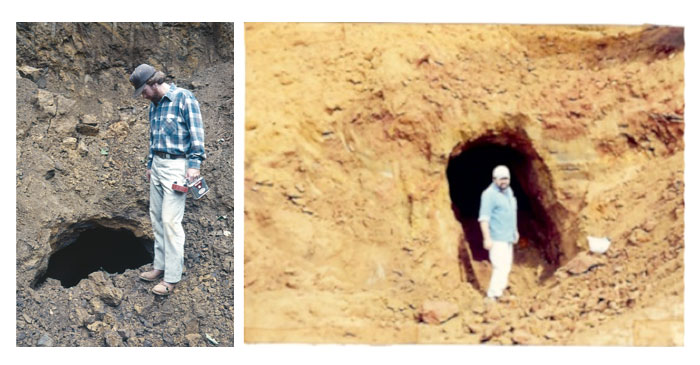

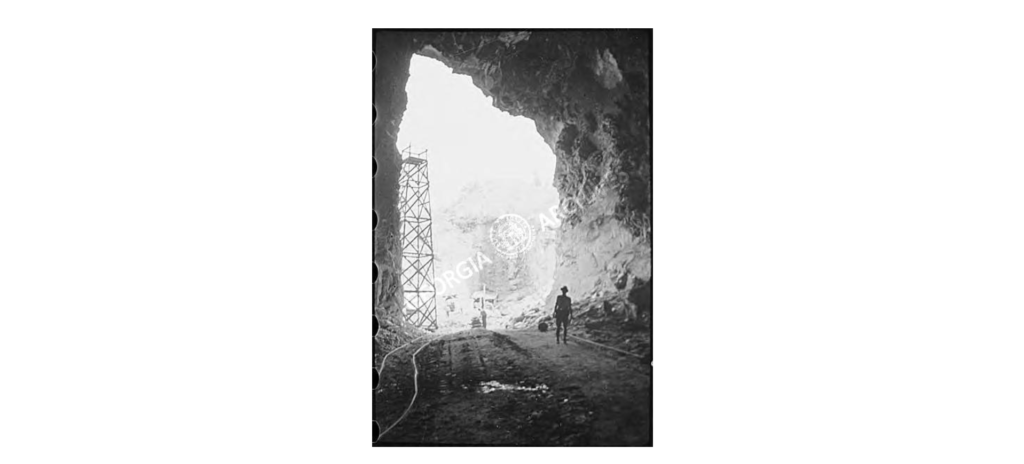

The photograph above is of a 1900 era tunnel that was uncovered by NRO while opening a pit mine in land lot 533 northeast of the NRO main office. It was previously known as the Wormelsdorf mine. The tunnel was about 10 feet below the current day surface. Open pit mining continued below this level to reach deeper deposits of ochre. However, NRO preserved this finding for study and documentation. The find also indicated a rail system had been in place to service this tunnel.

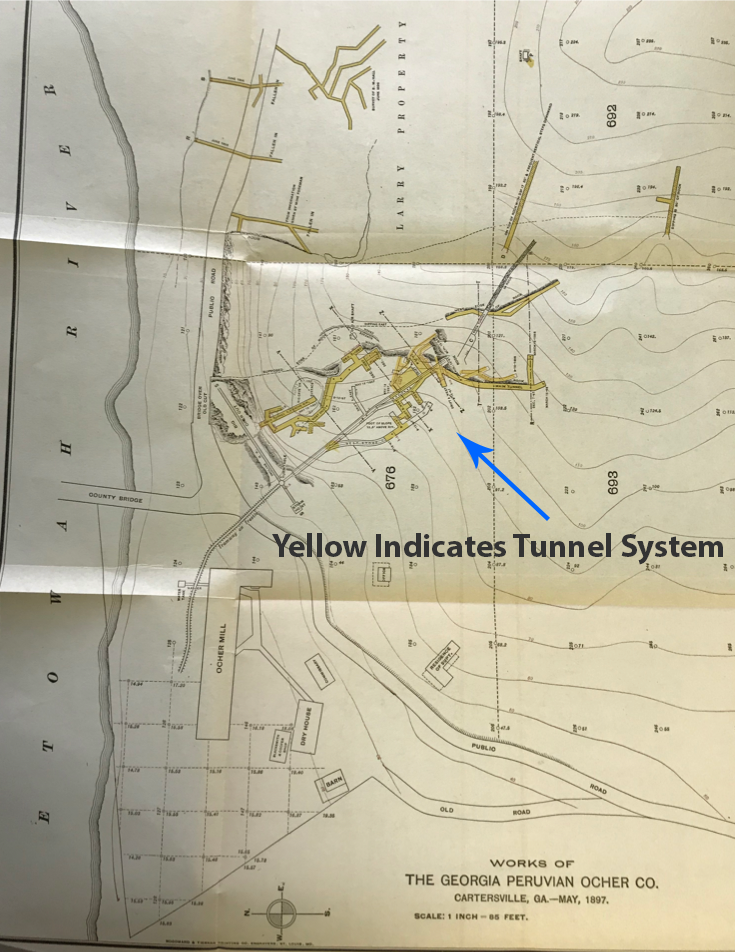

A system of tunnels is also known off of Paga Mine Road west of Highway 293 and south of the Etowah River in Land Lot 676. Here the Peruvian Ochre Mining Company of New York operated a series of ochre tunnels. Soon the Satterfield Mining Company (predecessor of NRO) established a competitive operation across the river. Today NRO owns the former Peruvian Ochre Mining Company and associated acreage.

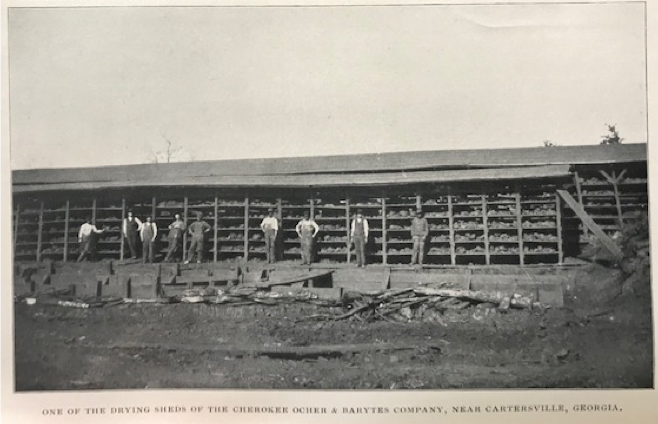

The Peruvian Ochre Company developed an active tunnel site with drying sheds, rail trams, processing house, rail turn table and roads. This site has been well documented by Dr. Thomas Watson in 1906 and illustrates the vast tunnel systems that once existed in the early mining history of Bartow County.

In northeast Bartow County was perhaps the greatest concentration of tunnels located in one operation. Located near Pine Log Mountain east of highway 411 north of Falling Springs Road was a mining quarry community known as Flexatile. Here an enormous deposit of slate was mined producing slabs of slate and granular material for roofing shingles. According to Mr. David Vaughan, owner of the property, the operation was conducted by digging a deep wide pit of several acres in scope and then digging horizontal tunnels into the banks of the pit. Mr. Vaughan states there were over nine miles of tunnels in this operation and when producing would create a vast amount of dust. The tunnels were named for famous New York city streets such as Broad Way, Park Avenue and Madison Avenue. The mining company that developed the site was Richardson Company followed by Funkhouser Incorporated.

About a mile northwest of Kingston was a very successful lime works next to the Western and Atlantic Railroad that became known as Cement, Georgia. Cement was established by Reverend Charles Howard in the 1850’s along with his Spring Bank School for women. Here he mined lime stone to manufacture cement and operated lime kilns to process the ore.

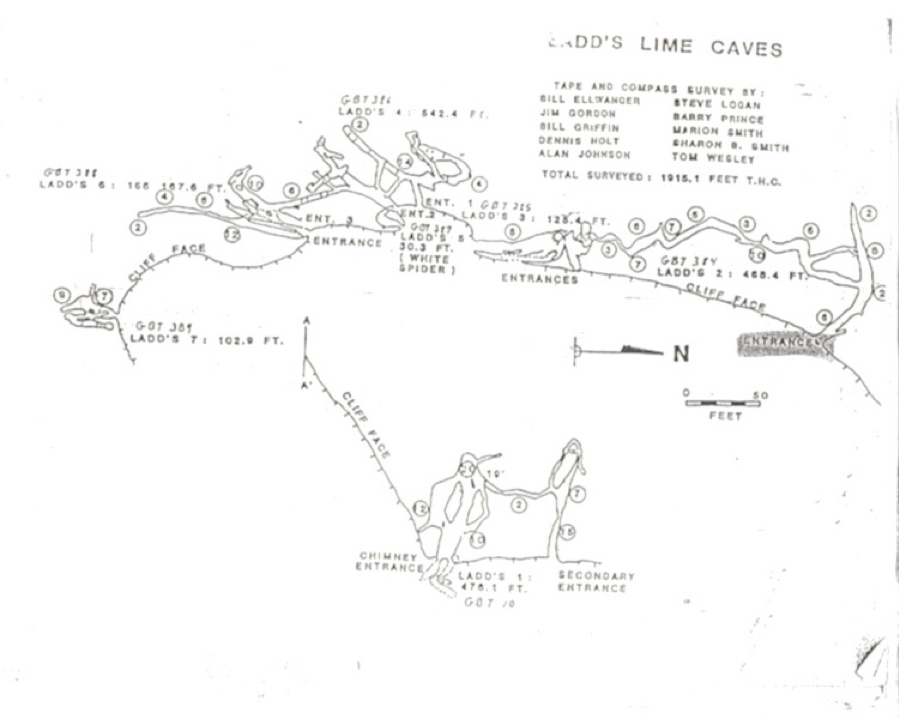

About two miles west of Cartersville on Hwy 113 is the legendary Ladd’s Mountain also known as Quarry Mountain. This site is also associated with historic Native Americans and particularly the Mississippian period. Here limestone and dolomite were mined. Initially natural caves were used to extract lime and then blasting was employed to bring down the front face of the mountain. Approximately 2000 feet of passageways were documented with a large cavern. It is thought that as many as a dozen entrances once existed.

However, Bartow mining history is not without catastrophes. The newspapers often reported mining accidents and deaths associated with railroad mishaps, cave-ins and collapses related to tunnels and bank cut ‘slick-head” slides.

One such accident occurred October of 1904 when a great mass of dirt, timbers and ore gave way and tumbled on a force of men working in the Morgan Mine cut. The iron ore mine was located slightly south east of Cartersville, (now east of I-75 south of Pine Mountain Trail Head) north of Old River Road. This accident appears to have received greater news coverage than any others found in this research.

The October 6, 1904 issue of Cartersville News and Courant reported that the mine had several side tunnels resulting in high mounds of dirt. The owner was moving among tunnel crews when the dirt gave way. Five men were buried in the accident including the owner of the mine, Mr. R. P. Morgan. Rescue crews arrived by train from Cartersville and Emerson. According to the paper Mr. Morgan and one other man were crushed to death. Morgan was also pierced by large splinters from a shattered tram car. Two others were recovered, but badly injured. The fifth man, a part time day laborer was never found.

Perhaps the best account of this accident appeared in the October 4, 1904 issue of the Atlanta Constitution. According to this report the mining site was about a 100 feet deep cut and 100 feet deep into the hill. Prior to the collapse a blast had just been made at one end of the cut creating a mass of dirt and ore to fall in the cut. Mr. Wheeler, a miner, saw a shaking of the earth and shouted a warning. The opposite side of the cut gave way and a massive slick head buried six men. Calls were made to Emerson and Cartersville for help. Thirty men arrived from the Kelley mine and sixty men from the Barton mine. It was estimated that 1000 tons of weight shifted and covered the men.

A century later, upon the arrival of Komatsu Corporation a heavy equipment training course was in operation that was built upon former mining acreage on the east side of I-75 near the Pine Mountain Trail Head. During excavator training an opening was discovered in the old Morgan mine area that held the remains of a victim.

On June 25, 2007, Brockington and Associates and the Bartow Coroner’s Office investigated the find and found scattered human bones with some other related clothing materials. An analysis of the remains and site suggested three scenarios of how the victim may have come to be in the shaft. The first was it may have been the grave of an early Bartow pioneer, the second was that someone had unfortunately fallen in the abandoned mine vent and perished there or the likely case that the remains appear to be the missing body of the 1904 Morgan Mine tragedy that was never found. The remains are now with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

A side benefit of the Brockington investigation uncovered a network of 21 vent ducts and 19 prospect shafts (tunnels) in the area associated with the human remains investigation. These mines were determined to be iron ore operations conducted by the Mansfield Mining Company.

A notorious network of mining camps and chain gangs once operated in the Sugar Hill Village near Pine Log in northeast Bartow County. The Courant American reported on October 20, 1889 that two Negroes were badly injured when a railroad trestle collapsed while riding ore cars. The Iron Belt Railroad and Mining Company was working the Guyton Ore Bank when the ore train crossed the creek. The engine crossed safely, but the trestle gave way as the ore cars passed over the span. Several men escaped serious injury, but several were hurt from being pummeled by the spilling ore and tumbling ore cars.

The legendary Lime Works at Ladd’s Mountain also was known to have tunnel shafts and natural caves. This mining site manufactured nitroglycerine for blasting the side of the mountain. In June of 1889, 700 pounds of nitro blew up destroying the building and near by machinery. The force of the blast shattered windows for a radius of three miles. Fortunately no personnel were injured in the explosion.

Perhaps one of the most horrific Bartow mining tragedies was the Chumley or Chumler Hill manganese mine located northeast of Cartersville off the Canton Road. The March 28, 1899 Courant American reported in two different articles that the men met a horrible underground death when a tunnel suddenly filled with water shutting off escape. The men were trapped over 220 feet below the surface. Once the men were reached they were all determined to have drowned. The follow up article describes in detail of the heroic efforts to recover the three men. It took a week to reach the trapped workers. The article relates that the shafts were about 4 feet wide and 6 feet high and how difficult the work was to remove the mud, water, debris and the exhaustion of the rescue teams. Some months later a 20 – year old miner fell forty feet down a shaft at the same mining site. He suffered crushed ankles, severe bruises and cuts, but survived.

In 1884 the Cartersville American Newspaper reported a fatal accident at the Dobbins Mine east of Cartersville, when a cave – in occurred instantly killing a worker and a second worker sustained wounds that he was not expected to overcome. A third worker was lost in the cave – in and was considered to be unrecoverable. The owner, Miles Dobbs was in the mine at the time and barely escaped. Recent heavy rains were blamed for the collapse of the banks.

According to an article in the July 24 1930, Tribune News a NRO workman was operating a steam shovel near the river when a cave-in occurred burying him. Quick work to recover him revealed he had suffered two broken legs and arm.

In August of 1947 an accident occurred at Flexitile/Funkhouser east of Pine Log when a huge block and tackle fell on Mr. Olin W. Boseman killing him instantly by bruising his upper torso and head. The device heavily damaged a near – by pump house and almost killing Mr. Fain Taylor.

Conclusion

Following the 1930’s, tunnel mining quickly faded and became lost to our heritage because it is less effective, unprofitable and not competitive. At least four generations have emerged since the end of the tunnel era. From the Greatest Generation and Baby Boomers to the Millennial Y’s and Z’s have little knowledge of the day when Bartow ore was pulled out of tunnels.

Tunnel mining of yester-year has given way to massive excavators capable of reaching great depths and moving enormous amounts of earth. As new technology is introduced and used to rescan former fields to locate undiscovered or deeper ore deposits, former tunnel networks are being uncovered and stand as a reminder of Bartow’s tunnel mining ancestors.

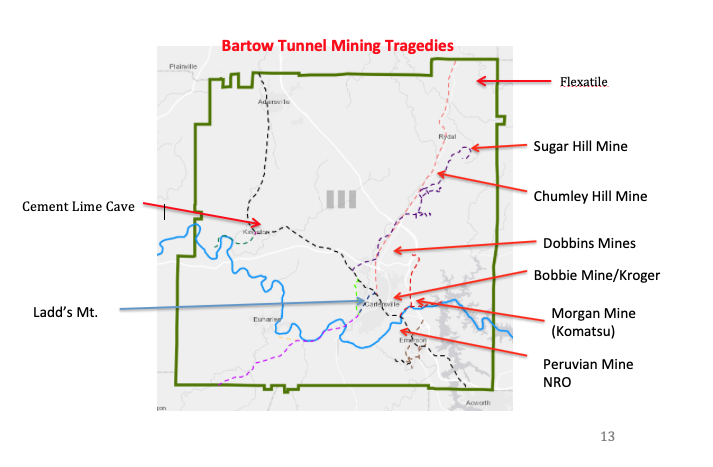

Approximate locations of tunnel mining featured in this article

Bibliography

Special Acknowledgment

A special recognition is extended to Mr. Stan Bearden as the primary consultant to this article for his professional expertise regarding his time and specialized knowledge to interpret this topic. Without his keen observation and alert to showcase this wrinkle in Bartow mining history, it may have perished without proper documentation.

Interviews and Field Visits

Mr. Stan Bearden, NRO Geologist and Vice President Operations, 6/25/ – 7/30/18

Mr. David Archer, Attorney, 6/26/10

Mr. Tom Deems, NRO President, 6/26/18

Mrs. Jodeen Brown, 7/11/18

Mr. Joel Guyton, Bartow County Coroner, 7/11/18

Mr. David Vaughan, 3/14/19

Mr. Joe Tilley, 3/38/19

Newspapers and State Archives

(Note, some article titles have been abbreviated)

Tribune News, July 24, 1930, Negro Workman Painfully Hurt

Courant American News, October 6th, 1904, Mining Catastrophe

Atlanta Constitution, October 4, 1904, Slick Head Causes Terrible Accident

Courant American News, September 13, 1900, Accident at Chumler Hill Mine

Courant American News, March 28, 1899, Shut Up In a Mine

Courant American News, March 30, 1899, Bodies Recovered

Courant American News, October 20, 1898, A Trestle Falls In

Courant American News, June 27, 1889, A Terrible Explosion

Cartersville American, February 19, 1884, Fatal Accident

Cartersville Tribune, August 21, 1947, County Singing Leader Killed

Archeologists/Geologists/Intern

Brockington and Associates, historical archeologist cultural resources consultants

3850 Holcomb Bridge Road, Suite 105 Peachtree Corners, Georgia 30092

Dr. Thomas Watson, 1906 Geological Survey of Georgia

Tracy Lusk, Bartow’s Mining Legacy, 2016, EVHS

Georgia Archives Digital Vault, Photo ID mmg24-2292a

Georgia Speleological Survey (GSS) Map of the National Speleological Society, 1972-1974