The Cutting Edge: Analysis of Pre-Contact Lithic Tools from the Cummings Site, Bartow County, Georgia

Kelsi Merkel

(Department of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University)

Published December 2025

Introduction

The study of lithic technology is one of the most informative approaches to understanding how past humans lived. Evidence from lithic analysis can interpret large-scale ideas such as how settlements were organized socially and politically, the prevalence of warfare, patterns of subsistence, and occupation periods, to more nuanced insight like what the typical person might have included in their daily toolkit that allowed them to facilitate their day-to-day activities. Thorough investigation of lithic artifacts is particularly useful in regions like northwest Georgia where organic materials are often poorly preserved, and within the southeastern United States, lithic analysis has been instrumental in refining chronologies and reconstructing the daily lives of prehistoric populations. The Cummings site, located in Bartow County, Georgia, offers an important opportunity to explore new methods of interpretation for the cultural material recovered to date by performing the first typological analysis on projectile points from the Cummings assemblage.

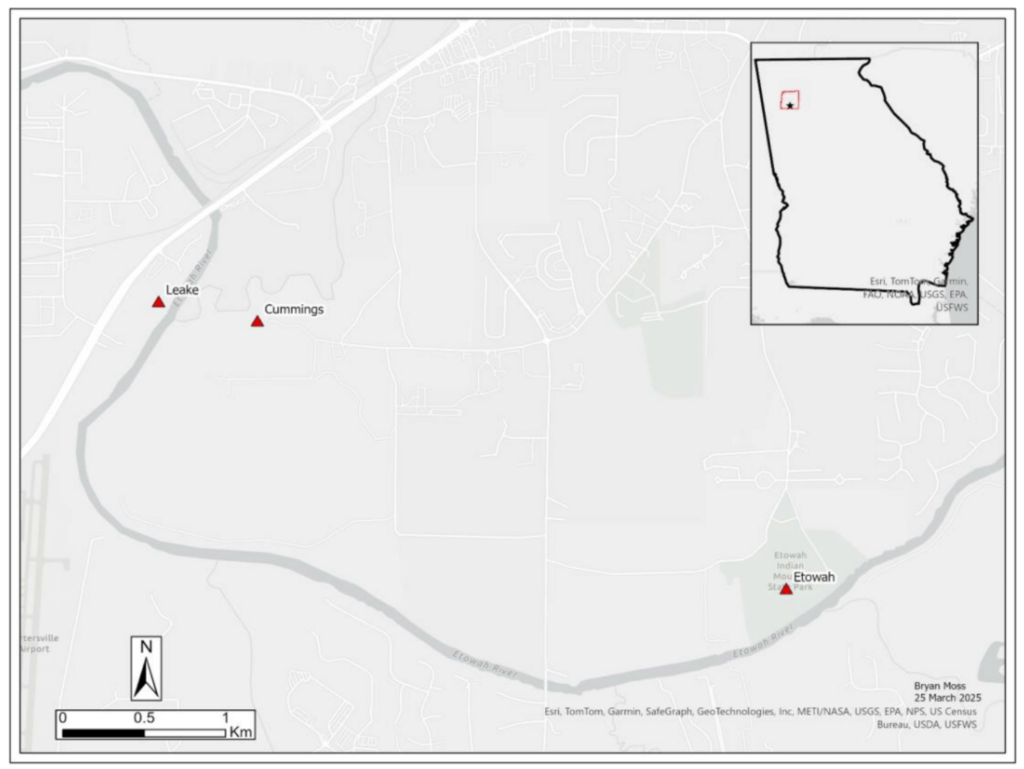

The Cummings site is located approximately three kilometers (2 miles) northwest of the Etowah Indian Mounds and roughly 500 meters (1650 feet) from the Etowah River (Figure 1). This strategic place within the river valley likely enabled access to diverse ecological and cultural resources, including proximity to sources of raw lithic materials such as the chert and quartz that was crafted into a variety of formal and informal tools. Cummings is also the site of an archaeology field school taught by Dr. Terry Powis at Kennesaw State University (KSU) and is excavated yearly by KSU students. Previous excavations at Cummings have produced ceramic and radiocarbon evidence suggesting occupations during the Early/Middle Woodland (1000 BCE-500 CE) and Middle Mississippian (1250-1375 CE) periods. The recovery of significant amounts of Dunlap Fabric Impressed pottery is one of the main indicators of an Early/Middle Woodland occupation, while the Mississippian ceramic assemblage includes a wealth of Savannah Check Stamped, Wilbanks Complicated Stamped, and Etowah types. Some other features associated with Early Woodland components include burnt wooden postholes that could be part of the remains of a house or other structure, a cobblestone feature, and a firepit feature. The main feature of the Mississippian component of the site is the remains of a house, which was dated through a radiocarbon assay and analysis of the associated ceramic materials.

Figure 1. The location of the Cummings site in proximity to Etowah and Leake in the Etowah River Valley, Bartow County. Map courtesy of Bryan Moss.

While ceramic and radiocarbon analyses have provided a chronological framework for the site, lithic materials from Cummings remain largely unexamined from a technological or morphological method. Therefore, my research provides the first detailed analysis of formal lithic tools recovered from the Cummings site. For this study, a total of 86 lithic artifacts were systematically categorized through metric and qualitative data collection and raw material identification. A comparative analysis with regional assemblages was used to determine tool type based on morphology and metric measurements. Through these analyses, my research aims to clarify the occupational sequence at the site, explore patterns of spatial use, and assess production strategies. Lithic analysis may also reveal information about how the prior inhabitants at Cummings engaged with local and regional resources, how their technological choices compare with those observed at other Woodland and Mississippian sites in the Etowah River valley—such as the local Hardin Bridge and Leake sites—and how they may have interacted with other contemporary sites via established trade routes. Ultimately, this study seeks to situate the Cummings site within the broader technological and cultural landscape of northwestern Georgia during the Woodland and Mississippian periods.

Background

The pre-contact history of the Southeastern United States is encompassed by four broad time periods: the Paleoindian period, the Archaic period, the Woodland period, and the Mississippian period. The Paleoindian period dates from around 11,500-8,000 BCE, and the people who populated North America at this time are widely associated with a distinctive style of projectile points. The Clovis point, widely found across the continental US, is characterized by its lance-shape and grooves running up from the base to one-half or less the length of the point (Hudson 1976). Many of these points are “fluted,” which refers to the process of detaching a flake from the base of the projectile point towards the tip, creating a groove that thins the base for hafting (Andrefsky Jr 2005). Paleoindians specialized in hunting large animals such as mammoth, camel, horse, and bison ancestors now extinct, and these points were probably hafted onto bone foreshafts, attached to spears that were used at close range for killing big game. In the later part of this period in the Southeast, projectile points began to change in shape, as flutes became less prominent and the bases became increasingly concave, often producing widely flaring ears, seen in Cumberland, Quad, and Dalton types (Hudson 1976). An assemblage of other kinds of stone tools was found at the Williamson site in Virginia, including small scrapers, spokeshave scrapers, knives, and gravers (Hudson 1976).

During the Archaic period (8,000-1,000 BCE), as climate changes greatly decreased the population of big game, Southeastern indigenous peoples had to diversify their food sources. Subsistence during this time was based on the gathering of vegetable foods, particularly acorns and hickory nuts, fishing, and hunting of small animals (Hudson 1976). People became increasingly sedentary, and consequently, the oldest North American pottery, dating to 2,500 BCE, was recovered from Stallings Island: a fiber-tempered pottery created by mixing clay with organic materials such as grass, roots, and Spanish moss. The discovery of a wide distribution of lithic raw materials from source areas in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions of South Carolina suggests that seasonal movements occurred up and down major river valleys, crossing the Fall Line at least twice a year (Espenshade and Patch 2008). Projectile points from this period frequently had stemmed bases or notches for attachment to shafts, and spears-throwers were developed for the use of increasing the force and distance of throwing spears (Hudson 1976). While the lithic technology of choppers and scrapers remained the same from the Paleoindian period, the Archaic period included objects made from polished stone; a range of items from milling stones and axes to pendants and beads were being crafted, demonstrating the use of polished stone for both utilitarian and decoration purposes (Hudson 1976).

The Woodland period (1,000 BCE-1,100 CE) includes three sub-periods: Early, Middle, and Late Woodland. This period is generally characterized by widespread use of pottery, increased sedentism, and a greater reliance on horticulture, although hunting and gathering continued to be an important subsistence strategy (Keith 2010). The acidic red clay soils of the Southeast make the recovery of animal remains at archaeological sites scarce, but limited assemblages indicate white-tailed deer and turkey were the most prevalent game, including also a wide diversity of small mammals and fish (Espenshade and Patch 2008). In northwest Georgia in particular, nuts such as hickory, acorn, black walnut, and hazelnut are part of plant subsistence (Espenshade and Patch 2008). Small settlements became increasingly sedentary and seasonal, with single-house dwellings and some pit houses found at sites within Middle Woodland context (Espenshade and Patch 2008). This shift to more permanent occupations is reflected in the widespread use of pottery. The Early Woodland is characterized by the presence of Dunlap Fabric Impressed pottery, while Middle Woodland yields Check Stamped and Simple Stamped pottery. Triangular point types (Yadkin, Eared Yadin, Copena) and small stemmed or weakly notched types (Coosa stemmed, Coosa notched) appeared in the Early Woodland and continued to be produced through the Middle Woodland, with the Late Woodland predominantly producing triangular points (Espenshade and Patch 2008).

The Mississippian period (1000-1540 CE) is divided into three subperiods: Early, Middle, and Late Mississippian. Overall, this is a period of significant population growth, defined by large settlement patterns, flat-topped mounds and plazas, permanent occupation, agriculture-based subsistence, and new ceramic types (Espenshade and Patch 2008). Sites were invariably built near rivers and streams where the best soil for agricultural needs was found and frequently surrounded by defensive walls (Hudson 1976). Subsistence was based on cultivated corn, beans, and squash, though hunting and gathering of native plants remained important; deer were likely hunted during the colder months and agriculture practiced during the warmer months, while additional protein sources from fish, mussels, and gastropods or trapped animals could be gathered year round (Espenshade and Patch 2008). The earliest ceramics of the Early Mississippian subperiod are sand/grit tempered wares with bold rectilinear designs, while Middle Mississippian pottery shifts to elaborate iconography suggesting organized religious practices, and Savannah and Wilbanks types becoming increasingly popular. The Late Mississippian period of the region is defined by the Lamar culture, associated with complicated stamp, punctation and incising ceramic types.

The Mississippian period is particularly marked by the establishment of chiefdoms and widespread social, political, and religious cultural manifestations across the Southeast (Espenshade and Patch 2008). The warfare patterns of Southeastern Indians were typically motivated by principles of revenge or retaliation, but in the Mississippian tradition, warfare designed to gain and defend territory became prevalent (Hudson 1976). During the time of European exploration in the Southeast, one chronicler alongside Hernando de Soto reported that Indian warriors used a range of weapons, including pikes, lances, darts, and clubs, but that their favorite weapon of war was the bow and arrow (Hudson 1976).

Methods

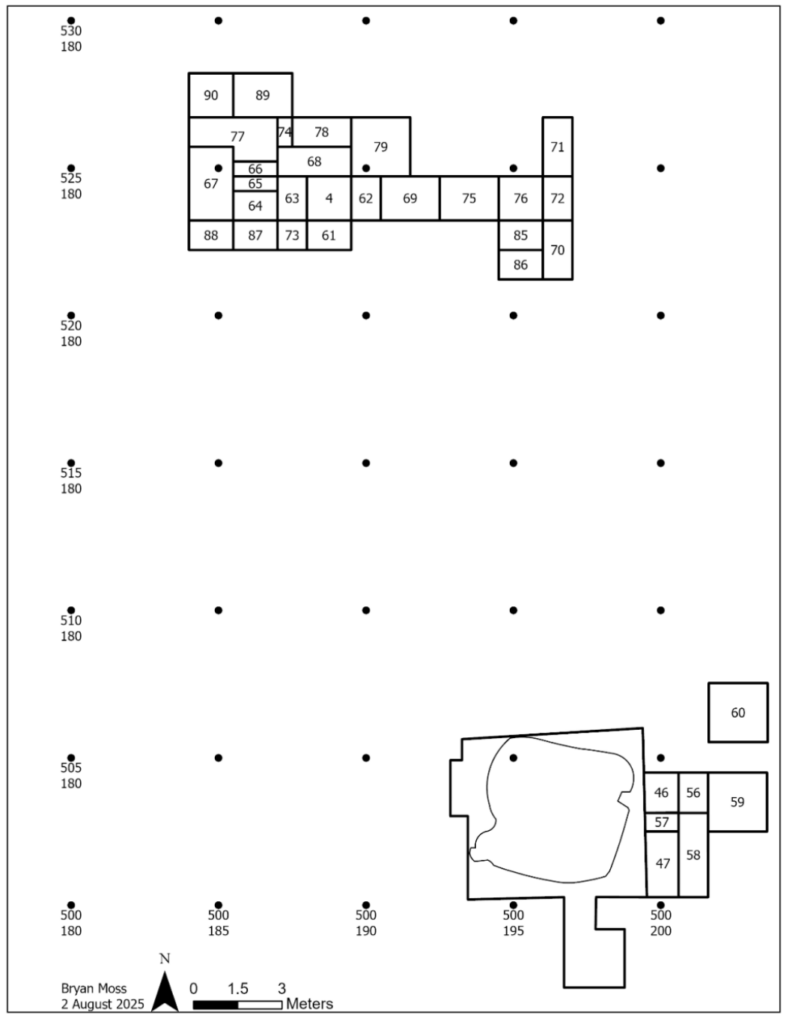

The first step in the research process was sorting through the pre-contact cultural material recovered from the Cummings site. I had access to all washed material recovered from excavation during 2023, 2024, and spring of 2025. Arbitrarily included was a projectile point from 2021 which was recovered from the floor of the feature labeled House 1, the Mississippian house uncovered in the south area of the site, and two projectile points from 2022, both recovered from Unit 65 (Figure 2). From each bag of washed artifacts, I sorted out the lithic material from non-lithic material, which included ceramic, animal bone, and natural materials. All historic materials had been previously removed. From the lithic material, I separated out any artifacts that displayed evidence of having been worked into a formal tool, which included complete and incomplete projectile points or PP/Ks (projectile point/knife), preforms, and possible scrapers. Projectile points can be a spear point, dart point, or arrowhead; preforms refers to an unfinished, unused form of the intended artifact, often denoting the first shaping of the tool and lacks the refinement of the completed tool; and scrapers refers to stone artifacts with a steep edge produced by removal of small flakes (Crabtree 1972). Many lithic tools are worked bifacially, meaning it has two sides (or faces) that show evidence of previous flake removal (Andrefsky 2005). In many cases hafted bifaces are used as knives and are resharpened (or retouched) when the knife becomes dull from use, and nonhafted bifaces may function as knives or scrapers (Andrefsky 2005), but the distinction between a lithic tool that is meant to be hafted on a long shaft like a spear rather than a short shaft to be used as a knife can be ambiguous, hence the amalgam of projectile point/knife. The artifacts used for analysis in this study were PP/Ks that had their bases intact. Each of these artifacts were separated into its own artifact bag with the original provenience information labeled on the front, and each artifact in addition was given its own catalogue number.

Figure 2. Map of the Cummings site showing unit locations. House 1, dating

to the Middle Mississippian period, is located in the bottom right of the map.

I then created a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel to record metric and qualitative data of the 86 artifacts deemed formal tools (Table 1). The spreadsheet is organized first according to provenience information, recording the excavation unit number, level and depth in centimeters, and whether the artifact was recovered in a cultural feature or not. The qualitative data listed includes base type, with some morphological notation, the type of lithic material, and whether the artifact was complete or not (whether the distal or farthest end of the PP/K was missing or not). Metric data includes haft length, base width, total length, and thickness. All measurements were taken in millimeters using a pair of digital calipers; the same calipers were used each time for the sake of consistency as measurements were recorded over a series of days.

A total of 68 out of 86 artifacts were successfully typed using several sources of regional comparative data. My main two sources for typing were John S. Whatley’s “An Overview of Georgia Projectile Points and Select Cutting Tools” (Whatley and Arena Jr. 2021) and Lloyd E. Schroder’s “The Peach State Guide to the Projectile Points of Georgia” (Schroder 2021). Digital copies of archaeological reports on the Leake site (Keith 2010) and the Hardin Bridge site (Espenshade and Patch 2008) were also used given the geographical and temporal relevance of these sites to Cummings. A second Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Table 2) was created to record the temporal range of the point type (Cameron 2020; Schroder 2021; Whatley and Arena Jr. 2021).

A brief analysis of chert and quartz debitage was also conducted to complement the lithic tool analysis. Debitage is defined as residual lithic material resulting from the manufacturing process (useful to determine techniques and technological traits) and can represent the various stages of progress of the raw material from the original form to the finished stage (Crabtree 1972). A total of 15 artifact bags were selected at random from excavation units and levels that corresponded to the provenience of recovered tools. For each bag, I again sorted lithic from non-lithic material with the purpose of gathering and separating all chert and quartz debitage. This material was further sorted into categories of shatter, primary flakes, secondary flakes, and tertiary flakes for both chert and quartz categories. A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was created to record qualitative and quantitative data of the debitage, which included material type, count, and weight in grams (Table 3).

Results

Out of the 86 lithic tools recovered and used for this study, a total of 68 (79.07%) were successfully typed through comparative analysis of metric and morphological data (see Table 1). The typed projectile points include: Woodland Spike (10), Small Savannah River (9), Otarre (8), Ledbetter/Pickwick (8), Coosa Stemmed (5), Savannah River Stemmed (4), Duval (3), Swan Lake (3), Camp Creek (2), Copena Classic/Triangular (2), Eared Yadkin (2), Elora (2), Mississippian Triangular (2), Kirk Corner Notched/Palmer (2), Kirk Corner Notched/Palmer/Autagua (1), Late Woodland Triangular (1), Allendale (1), Morrow Mountain I (1), and Swannanoa (1). The assemblage also includes one Rocker Based Blade. The most commonly occurring type was Woodland Spike, which supports the earliest identified occupation of the site.

Untyped tools were sorted into four additional categories based on morphology and inferred function: Untyped, Untyped Stemmed, Untyped/Blade, and Untyped/Possible Scraper. These tools were unable to be typed due to morphological variation and ambiguity, lack of comparative references, or because they were too fragmented to be accurately typed, despite having intact bases.

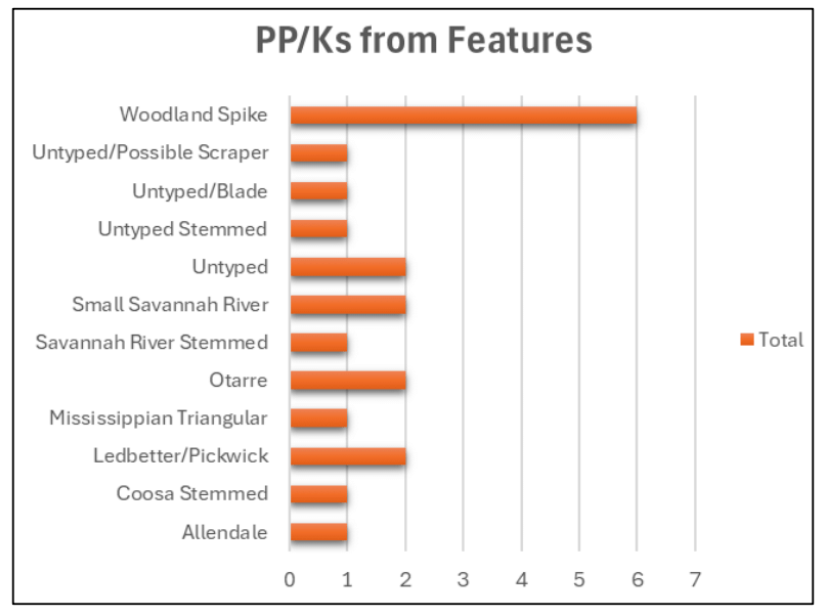

Twenty-one out of the 86 lithic tools were recovered from cultural features (Figure 3). These include: Woodland Spike (6), Small Savannah River (2), Otarre (2), Ledbetter/Pickwick (2), Savannah River Stemmed (1), Coosa Stemmed (1), Allendale (1), Mississippian Triangular (1), one untyped blade, one untyped stemmed pp/k, and one untyped possible scraper.

Figure 3. Artifacts recovered from cultural features.

Lithic Dating

Periods of occupation at the Cummings site are currently estimated from a combination of ceramic and radiocarbon dating from features. Survey and excavation in the Georgia Piedmont has provided a detailed ceramic sequence for the Mississippi period in northwest Georgia by 1950; all research conducted in the Valley and Ridge Province in subsequent years has relied on this sequence as a means for chronologically ordering artifact collections (Hally and Langford 1988). The radiocarbon dating of charred samples taken from features is the most reliable method for assessing accurate time periods of site activity as any artifacts recovered from features are likely to be in situ, meaning they retain their cultural context. Lithic analysis then provides a new method for explaining the chronology of occupation at the Cummings site, and by typing projectile points, particularly those that came from intact features that have been previously radiocarbon dated, I am able to support, contest, or expand upon previous findings.

As aforementioned, site activity dating to Early/Middle Woodland is supported by the presence of Dunlap Fabric Impressed pottery in the archaeological assemblage and the radiocarbon dates from burnt posthole and firepit features. Samples of charred posts from the remains of the Mississippian house (labeled House 1 for provenience) were given a date range of 1260-1300 CE by the Center for Applied Isotope Studies (CAIS) at the University of Georgia, indicating the house was constructed during the Middle Mississippian subperiod (Farkas 2021). Along with this charcoal sample, 38 pottery sherds were typed as Savannah Check Stamped and 40 sherds as Wilbanks Complicated Stamped (Farkas 2021). The Mississippian Triangular point recovered from the floor of House 1 is an excellent example of a temporal lithic tool found in context at the site, also opening up more avenues of cultural interpretation surrounding the type of tools used during this time period, who might have used them, and why.

Charred material from features in Units 78, 85, 78 + 89 have been radiocarbon dated as late Middle Woodland and contained 1 Otarre (1700 – 1000 BCE ), 1 Allendale (3550 – 3100 BCE), 2 Woodland Spikes (750 BCE – 850 CE), and 1 Ledbetter/Pickwick (3200 – 1200 BCE). The temporal range of these types encompasses Late Archaic and Early Woodland. Samples from features in Unit 70 have been radiocarbon dated to Late Mississippian and contained 1 Woodland Spike, a projectile point type temporally marked as Early/Middle Woodland.

Figure 4. Projectile points arranged to show order of chronology. Top row (L-R): Kirk Corner-Notched/Palmer, Morrow Mountain, Savannah River, Ledbetter/Pickwick; Bottom row (L-R) Coosa Stemmed, Swan Lake, Woodland Spike, Mississippian Triangle.

The typology of other points recovered from Cummings suggest even earlier periods of activity. Among the oldest points found are two Kirk Corner-Notched points and one Kirk Corner-Notched/Palmer/Autagua point dating to the Early Archaic period (7500 – 7500 BCE). The vast chronological range of projectile points from Cummings is represented by Figure 4. While there are yet no ceramic materials or radiocarbon dates that match these early temporal representations, the significant amount of projectile point types dated to the Archaic period are indicative of Archaic peoples’ interest in this location. It is likely that the proximity of Cummings to the Etowah River, as well as the abundance of walnut, hickory, and oak trees that grow in the area, would have drawn people to this area to gather resources and hunt the local fauna. Occupation during this era could have been seasonal or transitory, leaving less material in the archaeological record.

Production/Source Materials

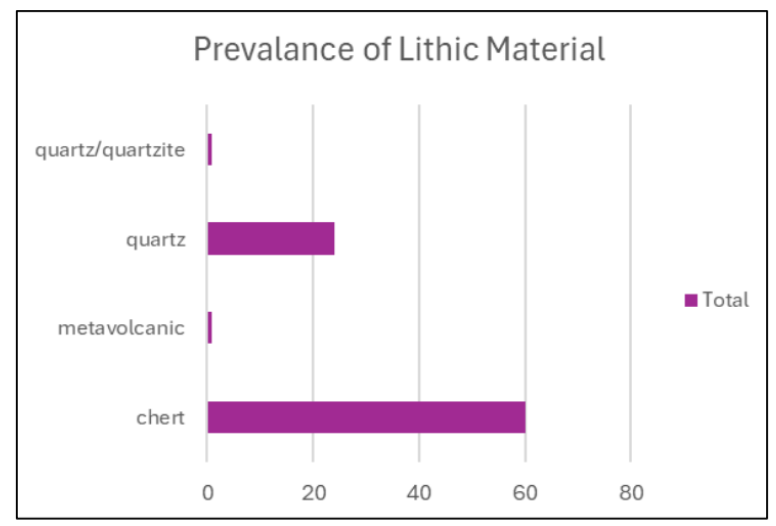

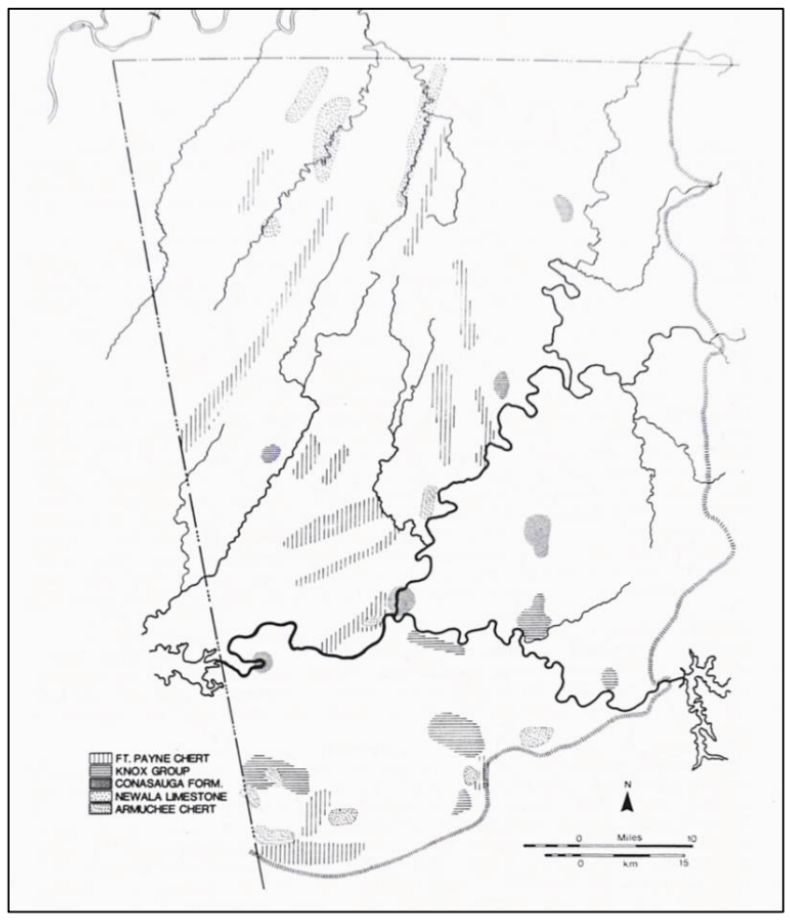

Analysis of projectile points, tools, and associated debitage from the Cummings site indicates a clear preference for chert as the primary raw material. Of the 86 projectile points analyzed, 60 were manufactured from chert, 24 from quartz, 1 from quartz/quartzite, and 1 from metavolcanic rock (Figure 5). This preference for chert material likely reflects both its superior knappability and its local abundance within the Ridge and Valley Province where the Cummings site is situated (Figure 6.)

Figure 5. Total count of lithic material.

Chert is a compact, siliceous mineral found in widely scattered outcrops generally associated with Paleozoic and Tertiary period limestones (Goad 1979). Common chert colors range from black, brown, white, yellow, grey, and red, a variation caused by different chemical impurities present during formation, such as carbons, irons, or magnesium (Goad 1979). Archaeologically, some of these color changes may be the result of deliberate heat treatment, a technique used to improve knappability by refining impurities in the material. Local Fort Payne chert is predominantly blue-gray in color, smooth and fine grained in texture with a high luster; when heated the chert becomes dark gray (Goad 1976). While specific heat-treatment indicators were not systematically recorded for the Cummings assemblage, it is noted that Coastal Plain chert, regional to southern Georgia, typically shows more alteration than chert from the Ridge and Valley, probably due to the excellent workability of unaltered Ridge and Valley chert (Goad 1979).

Figure 6. Distribution of Chert Resources in the Valley

and Ridge Province (Hally and Langford 1995).

Experimental archaeology of flintknapping demonstrates that high-quality chert fractures predictably in a conchoidal (or curved, shell-like) pattern and typically produces relatively little shatter, whereas quartz tends to fragment more unpredictably due to its internal crystal and grain size (Goad 1976). These characteristics make it particularly well suited for the production of bifacial tools and projectile points. It is likely that groups situated at a distance from chert sources would have required exchange networks with groups occupying chert-producing sites. The artifacts discussed in this report include at least one lithic tool that is probably quartzite, which comes from southern regions and suggests either trade or travel to acquire the material at its source. Quartz, by contrast, is widely available in the Piedmont and along the Cartersville Fault zone, where metamorphic and igneous rocks such as gneiss, schist, slate, and quartzite are common (Hally and Langford 1995).

Despite the ready availability of local quartz in northern Georgia, the prevalence of chert still dominates the debitage assemblage. The presence of primary, secondary, and tertiary flakes demonstrates the reduction of raw material from initial core preparation through to finishing stages and retouching. This flake categorization is based on the amount of cortex present (the natural surface for the rock), with primary flakes retaining complete natural surface, secondary flakes exhibiting partial cortex, and tertiary flakes lacking cortex entirely. The assemblage is characterized by a significantly higher proportion of tertiary flakes relative to primary flakes for both chert and quartz. This data, in addition to the bifacial preforms included in the cultural material from Cummings, suggest that the later stages of tool production and retouching were commonly conducted on site. In contrast, the comparatively low frequency of primary flakes could indicate that early-stage core reduction occurred elsewhere, probably nearer to raw material sources, with partially reduced material or preforms being transported to the site for final shaping and use.

A cross-referencing of Table 2 and Table 3 reveals some trends in lithic material usage compared to temporal type for projectile points. Goad’s (1979) report claimed that while quartz was frequently utilized at Woodland period sites in Georgia, very little chert was recovered from them (Goad 1979). The lithic tools analyzed for this project, however, show that the majority of Woodland period projectile point types were made of chert, while quartz made up a significant quantity of Late Archaic type projectile points. It is also noteworthy that two untyped scrapers and one untyped blade were made from chert, indicating the versatility of quartz in manufacturing many different types of tools. Given these findings, and the easy availability of local high-quality chert and quartz quarries to people in the Ridge and Valley region, it seems unlikely that a shift in lithic material usage is a result of sourcing difficulties. Socioeconomic and political interpretations could be further explored to explain these trends, as well as considerations into the correlations between tool type and lithic material.

Form and Function

One of the main questions brought up during this study is whether the morphological variation of lithic tools is a direct reflection of functionality. Projectile point typologies frequently distinguish tools based on size, shape, and basal modification, yet I found that metric and stylistic overlap and inconsistencies complicated the categorizing of these artifacts. One explanation for these variations might have to do with the skill of the flintknapper; as flintknapping is a challenging craft requiring a significant amount of time and material to master, an experienced flintknapper is likely to produce stone tools with more consistent technique than an amateur. Variation might also be caused by expedient production. Similar to how flakes can be struck off the core of raw cobbles, used briefly for cutting or scraping, and then discarded after serving its purpose as an informal tool, some stone tools may be worked just to the degree of being effective in use. This could be a consequence of warfare, which was particularly endemic during the Mississippian period. If conflict prompted the need for mass production of projectile points, the knapper might not be concerned about consistency so much as making sure their spears or arrows had points on the end of them. Mass production of this kind could have also employed non-experts in making projectile points. Another interpretation is that the breaking and retouching of projectile points creates morphological variation in type categories, as the process of reworking a stone tool will reduce the size of it. For example, retouched Kirk Corner-Notched points can be mistaken for Palmer points, or it is possible that all Palmer points might be Kirk Corner-Notched points with retouch (Whatley and Arena Jr 2021). It was therefore prudent for this project that temporal markers like ceramic types and radiocarbon dates associated with the lithic assemblage were taken into consideration during projectile point typing.

Lithic tool types such as awls, drills, knives, scrappers, hammerstones, and burnishing stones suggest an explicit function, but can an argument be made that morphological analysis can directly determine how a tool was used? According to Crabtree (1972), typology based only on shape can imply function, but more pertinent to lithic study is the analysis of various stages of the manufacturing process, which can reveal more about technique and functional need. Tools with identical forms may have been produced through vastly different techniques and served different purposes, and Crabtree (1972) emphasizes that shape and functional performance of the tool depends more on the quality of the material and the skill of the worker. The quality of raw material, such as chert, obsidian, or quartzite, directly influences edge sharpness, durability, and tool shape. Thermal alteration is a process through which the quality of lithic materials could be improved, which involves slowly heating up the stone and leaving it to cool, making the stone more vitreous so that it can be worked to a much sharper edge. For tasks involving digging, scraping, or boring, toolmakers favored tougher materials (Crabtree 1972). This preference for durability over sharpness is evident in the recovery of groundstone axes from the Cummings site. The use of hammerstones, for quarrying stone and percussion flaking in the production of stone tools, illustrates how technological considerations shape tool form. The choice of hammerstone material, ranging from hard stone to softer materials such as bone or wood, will result in different flake morphology (Crabtree 1972). Softer percussors prolong the interval of contact and are better suited for controlled flake removal, while harder percussors produce shorter, sharper impacts (Crabtree 1972). These factors demonstrate that lithic form emerges from a dynamic interaction between material quality and production choices, rather than from intended function.

A study done on the differing attributes of recent Indian projectile points also concluded that no single morphological trait can reliably differentiate arrowheads from darts without discriminate testing (Erwin et al 2005). The aim of the study was to test the theory that the stylistic shift in projectile points during the transition between the Beaches complex and Little Passage complex on the island of Newfoundland was due to the adoption of the bow and arrow. An analysis of size, shape, and notch type was conducted for 840 projectile points. The results indicated a substantial overlap in arrowhead and dart-head lengths, suggesting that while the length of a point is significant, it is not a key factor in distinguishing arrows from darts (Erwin et al 2005). Their analysis further showed that corner-notched and side-notched forms of projectile points were not tied exclusively to either dart-throwing or bow and arrow technology, and therefore function cannot be assumed from form alone (Erwin et al 2005).

This is particularly relevant to the Late Woodland and Mississippian contexts of my research. The introduction of bow and arrow technology to the Southeast by approximately 700 CE could be associated with the emergence of small triangular projectile point types, such as the Late Woodland Triangular and Mississippian Triangular points recovered from Cummings (Figure 7). To once again reference the projectile point chronology in Figure 42, the morphological changes in Southeastern projectile points over time are obvious, but not necessarily representative of a trend in shifting weapon technology. It is likely that Mississippian Triangular points were used as arrowheads, given their easily reproducible small size and shape, but that is not to say they could not have also been used as multi-tools. Early Archaic points like Palmer and Kirk Corner-Notched and Early Woodland points such as Swan Lake and Woodland Spike are also relatively small, yet predate bow and arrow technology in the Southeast. While shifts in point size and style might correlate broadly with technological change, it shouldn’t be assumed that function can be inferred solely from typology. Rather, lithic analysis should consider manufacturing techniques, raw material selection, use-wear and residue analysis when trying to understand tool function.

Figure 7. (Top) Late Woodland Triangular; (Bottom) Two Mississippian Triangular.

Conclusions

Despite substantial archaeological attention to major mound centers such as Etowah and Leake, comparatively less is known about the smaller habitation sites that supported and interacted with these preeminent sites. The Cummings site provides a wealth of cultural material and an opportunity to learn about pre-contact societies in broad terms, such as the social, political, and economic networks that connect Cummings to its contemporary neighbors, as well as a more nuanced view of day-to-day life at this site. The application of lithic analysis on this cultural material was able to provide evidence on site activity, site chronology, and stone tool use and production strategies.

While current interpretations of site occupation are based primarily on ceramic typologies and radiocarbon dates, this study demonstrates that lithic analysis offers significant evidence to broaden the previously defined chronology. The analysis of 86 formal lithic tools, of which 68 were successfully typed, reveals a temporal range of activity at Cummings extending from the Early Archaic through the Mississippian period. The prevalence of Woodland Spikes supports a substantial Woodland occupation, while the recovery of Mississippian Triangular points from contextually secure features, like the floor of House 1, supports a Middle Mississippian presence at the site. These findings suggest that the location was utilized well before the Woodland and Mississippian periods.

Raw material and debitage analyses were used to explore trends of lithic production and technological choices. The dominance of high-quality local chert, combined with the abundance of tertiary flakes, preforms, and finished tools, indicates efficient production strategies focused on later-stage reduction and tool maintenance conducted on site. It was also noted that the variability observed in projectile point morphology can be due to many reasons, including retouching, expedient toolmaking, or simply the skill of the toolmaker. Furthermore, the relationship between tool shape and function is explored, and it is determined that morphology alone cannot reliably discern function. Future research that includes analysis on the heat treatment of chert and quartz for tool making, and the sourcing and identification of the lithic material used, would be beneficial to further understanding technology and production trends and could reveal trading networks between Cummings and other sites.

Acknowledgements

My immense gratitude to Dr. Terry Powis for overseeing this project and providing me with the necessary research materials and the academic guidance to make this project possible. Thank you to Ava Armstrong for helping with organization and efficiency in the Archaeology Lab at KSU as well as providing necessary equipment for my photography needs.

Table 1. Provenience information, metric data, and projectile point type.

Table 2. Temporal data.

Table 3 Key:

CS = Chert Shatter

C1 = Chert Primary Flake

C2 = Chert Secondary Flake

C3 = Chert Tertiary Flake

QS = Quartz Shatter

Q1 = Quartz Primary Flake

Q2 = Quartz Secondary Flake

Q3 = Quartz Tertiary Flake

Table 3 Key:

CS = Chert Shatter

C1 = Chert Primary Flake

C2 = Chert Secondary Flake

C3 = Chert Tertiary Flake

QS = Quartz Shatter

Q1 = Quartz Primary Flake

Q2 = Quartz Secondary Flake

Q3 = Quartz Tertiary Flake

References

Andrefsky Jr., William. 2005. Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, Christopher A. 2020. Georgia Projectile Points: Identification & Geographic Range. Durham, NC: Field Technologies, Inc.

Crabtree, Don E. 1972. An Introduction to Flintworking. Pocatello, ID: Idaho State University Museum.

Erwin, John C., Donald H. Holly, Stephen H. Hull, and Timothy L. Rast. 2005. “Form and Function of Projectile Points and the Trajectory of Newfoundland Prehistory.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie 29 (1): 46–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41103516.

Espenshade, Christopher T. and Shawn M. Patch. 2008. A Middle Woodland Household on the Etowah River: Archaeological Investigations of the Hardin Bridge Site, 9BR34. New South Associates.

Farkas, Jordan. 2021. “Home Sweet Home: An Architectural Analysis of Native American Houses During the Middle Mississippian Period in the Etowah River Valley.” Etowah Valley Historical Society.

https://evhsonline.org/archives/50560.

Goad, Sharon I. 1979. Chert Resources in Georgia: Archaeological and Geological Perspectives. Report Number 21. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology.

https://archaeology.uga.edu/sites/default/files/2021-12/uga_lab_series_21.pdf.

Hally, David J. and James Langford. 1995. Mississippi Period Archaeology of the Georgia Valley and Ridge Province. Report Number 25. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology.

Hudson, Charles. 1976. The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press.

Keith, Scot J. 2010. Archaeological Data Recovery at the Leake Site, Bartow County, Georgia. New South Associates.

Schroder, Lloyd E. 2021. The Peach State Guide to the Projectile Points of Georgia. Lulu Press.

Whatley, John S., and John W. Arena Jr. 2021. An Overview of Georgia Projectile Points and Select Cutting Tools. 2nd ed. Columbia, SC: Archaeological Society of South Carolina, Inc.