Natalie Mason

Department of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University

Dani Hopkins

Department of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University

Fall, 2025

Introduction

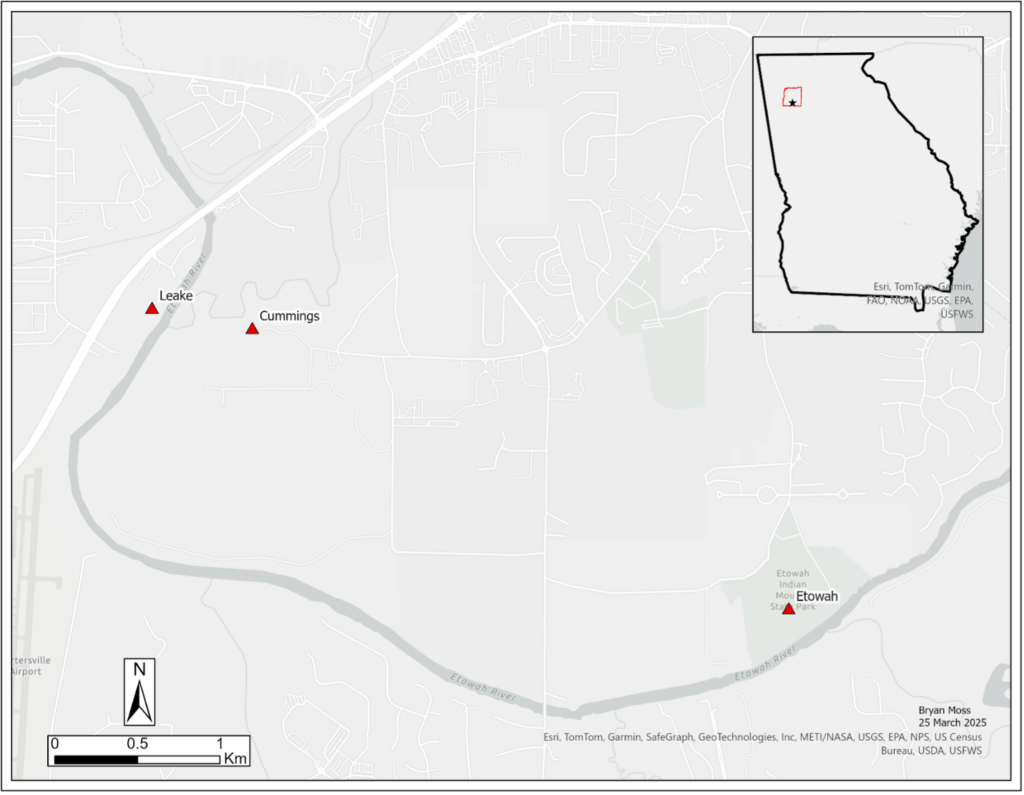

This research focuses on the recovery and analysis of ceramic pulley-style earspools from the Cummings Site, located approximately three kms (2 mi) within proximity to the Etowah Mounds and the Leake Site – two of the most prominent precontact sites in the Etowah River Valley, Bartow County, Georgia. The site itself reflects periods of occupation, notably the Middle Woodland (300 BCE-600 CE) and Middle Mississippian (1250-1375 CE), providing a rare opportunity to study cultural continuity and transformation within this archaeologically rich landscape. This site has been the location of an archaeological field school taught by Dr. Terry G. Powis for the past eight years. Intensive investigations have been conducted here to train Kennesaw State University students in the proper methods and techniques for working in archaeology, gaining insight into the complexities of the precontact Southeast.

Excavations conducted under the direction of Terry Powis revealed two remarkable ceramic pulley-style earspools — artifacts that challenge established understandings of adornment, status, and trade during this period. Unlike the more familiar copper earspools associated with the Hopewellian exchange system (Ruhl 1992), the Cummings Site examples are crafted entirely from fired clay, an exceptional material choice for objects of this type. Their discovery within a midden—a refuse deposit rather than a burial or ceremonial context—suggests a more complex story of manufacture, use, and cultural significance.

Examination of the pulley-style earspools provides insight into the materials used for the construction of the earspools, the source of these materials, and the overall craft production. In order to properly assess trade routes, it is significant to examine the traces of materials present in the earspools. This research also aims to assist in identifying how these earspools were used at the site.

Background

The Middle Woodland period (300 BCE-600 CE) represents one of the most dynamic eras in North American prehistory, characterized by extensive long-distance exchange networks, increasingly elaborate material culture, and the rise of monumental earthworks and mounds that signified complex social and ceremonial life (Figure 1). Across this landscape, communities participated in vibrant systems of interaction that linked distant regions through the exchange of goods, ideas, and symbols of prestige. While the Hopewellian tradition of the Ohio River Valley has long defined the archetype of this era—known for its intricate ceremonialism, mortuary practices, and expansive trade in copper, mica, and marine shell—regional variation remained substantial (Ruhl and Seeman 1998). In the Southeastern United States, these influences found localized expression in cultures such as the Swift Creek tradition (100-800 CE), which flourished across Georgia and neighboring areas. Swift Creek people were particularly renowned for their finely crafted curvilinear-stamped pottery, a hallmark of both technical skill and shared cultural identity (Smith and Knight 2012).

Figure 1. The Cummings site (and associated sites) along the Etowah River. Courtesy of Bryan Moss.

Despite their importance, Swift Creek sites in Georgia have historically been underrepresented in archaeological research, largely due to an emphasis on mound centers rather than village and habitation sites. The discovery of Swift Creek pottery sherds at the Cummings Site thus provides crucial evidence for the region’s participation in the broader Middle Woodland interaction sphere. These materials illustrate how local communities along the Etowah River (Figure 1) were active participants in exchange systems that linked them to distant peoples across the Southeast and beyond.

Within these networks, elite goods such as copper breastplates, earspools, celts, and marine shell ornaments circulated as markers of social rank, ceremonial power, and creative expression (Carter 2015; Ehrhardt 2009). The Cummings Site earspools, however, deviate strikingly from these norms. Crafted from fired clay rather than copper, they represent a rare and localized adaptation of broader Hopewellian and Swift Creek traditions. Their presence suggests that communities in the Etowah Valley were not merely passive recipients of external influences but active innovators, translating symbols of status and identity into new forms that reflected their own cultural values and resources.

The use of earspools as body ornaments has deep and cross-cultural significance. Across the ancient Americas—from Mesoamerica to the Southeastern United States—these objects were often associated with ritual identity, status display, and transformation of the body as a sacred medium (Ruhl 2005). The Cummings examples extend this legacy, connecting the prehistoric Southeast to a global continuum of body modification practices. Even today, the tradition of ear stretching continues in contemporary societies, echoing millennia-old expressions of identity and aesthetic transformation first envisioned by ancient artisans of the Woodland world.

Methodology

Both earspools were recovered from Feature 7 in Unit 78 at the Cummings Site (Figure 2). This feature was identified as a midden, or refuse deposit, composed of discarded materials (e.g., broken pottery vessels and stone tools) from daily and possibly ritual activities. Among the items excavated from this context were Swift Creek pottery sherds and a rolled copper bead (Figures 3 and 4), each providing important clues to the cultural affiliations and activity patterns at the site.

Figure 2. Feature 7 (represented by dark stain) in Unit 78. Courtesy of Terry G. Powis.

Figures 3 and 4. Both artifacts were found in the same feature as the earspools. Top: Swift Creek pottery; Bottom: a rolled copper bead.

The analytical process began with the reconstruction of the fragmented earspools, an intricate undertaking that revealed both the skill of the original artisans and the care required for modern conservation. At first, researchers hypothesized that the fragments represented a single, unusually large earspool—perhaps an ornamental piece worn around the neck or used in display rather than as a functional ear ornament. However, closer study of the curvature, thickness, and break patterns demonstrated that the pieces in fact represented two distinct artifacts. This was proven when the pieces then matched up into a pair.

Each fragment was carefully cleaned, sorted, and reassembled using conservation-grade adhesives to ensure long-term stability. Once reconstructed, the artifacts (Figure 5) were precisely measured using digital calipers, weighed on a Scout Pro scale, and their complete dimensions and estimated full weights were calculated. The more complete spool measured approximately 98 mm (3.8 in) in diameter and weighed 75 grams (0.16 lbs)— exceptionally large compared to known examples from the region.

Figure 5. Reconstructed earspools.

With their overall form restored, new insights emerged into the manufacturing techniques and stylistic decisions of their creators. Subtle tool marks and shaping irregularities indicate that these earspools were hand-modeled rather than wheel-formed, and that their dark surface finish was likely achieved through controlled firing or burnishing (Figure 6). Such attention to surface treatment reflects both technical skill and aesthetic intention, underscoring the craftspersons’ understanding of form and symmetry.

Figure 6. Reconstructed earspool (closeup of larger earspool on the right side of Figure 5). Note the pulley-style indentation and dark finish.

To contextualize the Cummings Site earspools within broader Middle Woodland exchange and stylistic systems, the research team conducted radiocarbon dating on associated charcoal samples. The sample (UGAMS #74896) is dated to 427-538 CE (95.4% Confidence; mean CE 478). The results coincide with the height of the Swift Creek interaction sphere and a late Middle Woodland date for Feature 7 at the Cummings Site. Given the Cummings Site’s proximity to the Leake Site—a major regional hub for trade and ceremonial exchange (Keith 2020)—it is plausible that these earspools were either locally produced as imitative prestige items or obtained through interregional trade networks connecting the Etowah Valley to distant cultural centers.

Finally, through a comparative analysis of similar artifacts from other Swift Creek–affiliated sites, the Cummings examples were situated within a wider stylistic and cultural framework. This examination not only highlights regional variation in artifact design but also provides valuable insight into the social symbolism, trade dynamics, and artistic expression that characterized the Middle Woodland Southeast. The reconstruction of these objects, therefore, represents more than technical restoration — it is a process of reassembling ancient networks of identity, exchange, and craftsmanship embedded in clay.

Results

The reconstructed earspools from the Cummings Site reveal remarkable variation in preservation, craftsmanship, and morphology, offering a rare opportunity to examine the nuances of Middle Woodland ceramic adornment. The more complete specimen measures approximately 98 mm (3.8 in) in diameter with an average width of 21.7 mm (0.9 in), while the more fragmented example averages 20.7 mm (0.8 in) in width. The central aperture of the larger piece spans roughly 55.7 mm (2.2 in), bordered by a pulley-style indentation measuring about 4 mm (0.2 in) deep—a design feature characteristic of body ornaments intended to sit within stretched earlobes or to emulate such adornments visually.

Approximately 60% of the more intact earspool survives, weighing 75 grams (0.16 lbs), which allows for an estimated full weight of around 125 grams (0.3 lbs) when complete. Both objects were carefully fashioned from a reddish-brown fired clay with a dark, burnished finish, reflecting deliberate surface treatment and firing control by the original craftsperson. Their composition distinguishes them sharply from the copper earspools more commonly associated with elite Hopewellian or Mississippian contexts.

Radiocarbon dating of associated charcoal situated the deposit securely within the Middle Woodland period, with a median probability of 478 CE. This date aligns precisely with the height of the Swift Creek interaction sphere, a regional cultural network known for its distinctive curvilinear-stamped pottery and participation in far-reaching exchange systems. The presence of Swift Creek pottery sherds directly associated with the earspools further strengthens this connection, suggesting that the individuals who produced or deposited these artifacts were active participants in the broader social and artistic milieu that characterized the Middle Woodland Southeast.

The Cummings Site sits in proximity to the Leake Site, which is only 0.75 kms (0.5 mi) to the west. This geographical relationship provides additional interpretive context. The Leake Site functioned as a major Woodland-period hub for exchange, ceremonial activity, and the circulation of prestige goods, including copper ornaments and exotic ceramics (Keith 2020). It is plausible that the Cummings earspools were either locally produced in imitation of higher-status materials or acquired through exchange networks radiating outward from Leake (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Leake site (star) and the waterways that facilitated exchange with the rest of the Hopewellian world.

Despite these associations, the Cummings earspools stand apart from any known regional or temporal parallels. They predate Mississippian body modification artifacts by several centuries, and unlike most examples recovered from mortuary or ceremonial contexts, these were discarded in a midden, indicating a possible break in symbolic or functional use. Their large size, substantial weight, material composition, and lack of decoration make them unique within the Southeastern archaeological record.

These exceptional traits invite deeper inquiry into their purpose and meaning. Were they practical ornaments meant to be worn, symbolic representations of status, or ceremonial prototypes crafted to emulate elite goods? Their exaggerated proportions may suggest a nonfunctional or symbolic intent, perhaps serving as ritual displays, artistic expressions, or markers of cultural aspiration within the Swift Creek sphere. Whatever their precise role, the Cummings earspools offer a powerful testament to the creativity, experimentation, and social complexity of Middle Woodland communities in the Etowah Valley, illuminating a fascinating chapter in the evolution of personal adornment and identity in the prehistoric Southeast.

Discussion

The ceramic pulley-style earspools recovered from the Cummings Site represent an exceptionally rare and thought-provoking discovery within Southeastern archaeology. Their recovery from a midden context, rather than from a mortuary or ceremonial deposit, is particularly unusual for this artifact type, which is typically associated with elite adornment and ritual display. Equally remarkable is their material composition—crafted not from copper, shell, or other prestige materials characteristic of the Middle Woodland period, but from fired clay, a medium seldom employed for body ornaments of such scale or sophistication.

Perhaps most striking, however, is their extraordinary size. These earspools surpass most known examples in size, averaging 98 mm (3.8 in) in diameter and 125 grams (0.3 lbs) in weight, setting them apart not only regionally but across temporal and cultural boundaries. Their form places them within a much broader global tradition of body modification and personal ornamentation, one that transcends geography and time. From the elaborate body adornments of Mesoamerican elites to Mississippian-period copper ear ornaments and even Old World societies that practiced ear stretching as a marker of status or identity, the impulse to modify and embellish the human body appears to be a shared human expression of belonging, prestige, and transformation.

Modern American subcultures have adopted the use of earspools for similar reasons, even pushing said body modifications to the extreme. Marc Greenleaf of Wyoming was awarded the Guinness World Record for the largest stretched earlobes in April of 2024, when his earlobes measured 118.4 mm (4.7 in) in diameter–but he’s since stretched them an additional 12.7 mm and taken to wearing earspools that weigh in at 226.8 grams (0.5 lbs) each (a full 100 grams or 0.2 lbs) more than the estimated weight of the whole Cummings site earspools). Why? Curiosity, he told Cowboy State Daily writer Anna-Louise Jackson. He cited a casual competition with himself to see how far he could stretch them. Perhaps novelty was the motivation that drove the makers of the Cummings earspools. We will likely never know. The size of Greenleaf’s earspools proves that the Cummings earspools could, theoretically, be worn, but Greenleaf might be the exception that proves the rule: it’s unlikely that the Cummings earspools were actually worn in stretched earlobes.

In this light, the Cummings earspools may have carried symbolic or aspirational meaning rather than practical function. While their reconstructed size suggests that they could theoretically have been worn, doing so would have required extensive, intentional stretching over many years. Greenleaf’s self-directed process for stretching his earlobes took commitment–an extremely painful process learned by trial and error, according to Jackson. This makes it equally plausible that they served as display objects, ritual prototypes, or symbolic emulations of high-status ornaments crafted in more prestigious materials. Their discard in a refuse pit rather than in a burial may reflect this ambiguity of purpose — perhaps representing failed experimental pieces, objects no longer valued, or symbolic items retired from use after fulfilling a ceremonial or artistic role.

Alternatively, their exaggerated dimensions and use of a humble medium may represent a deliberate artistic statement—a creative reinterpretation of elite symbolism through local materials and techniques. Such an approach would align with known patterns of Swift Creek artistic expression, in which artisans balanced adherence to regional styles with local innovation and experimentation. The technical proficiency evident in their manufacture—symmetrical shaping, burnished finish, and careful proportioning—further underscores the intention and artistry invested in their creation, even if their exact function remains uncertain.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the Cummings Site earspools invite deeper reflection on why humans alter and adorn their bodies, and how such practices communicate identity, aspiration, and social belonging. Whether expressions of status, aesthetic experimentation, or cultural mimicry, these artifacts illuminate a shared human fascination with the body as a canvas of meaning. In their exceptional form, enigmatic purpose, and unconventional material, they contribute new insight into the creativity and complexity of Middle Woodland material culture in the Etowah River Valley. In this region, art, identity, and exchange converged in enduring and innovative ways.

Further research on material analysis, experimental archaeology, and stylistic comparison can be conducted to expand on this study and deepen our understanding of these enigmatic objects and the people who created them.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Terry Powis for his continued support and guidance throughout this research. His provision of essential resources, photographic equipment, and methodological direction greatly contributed to the success of this project. His dedication to students at the Kennesaw State University archaeological field school is especially appreciated. We would also like to thank Sam Kemp for assistance during the initial phase of this project, particularly for the Symposium of Student Scholars in the Spring of 2025. Our gratitude goes to Ann Cummings for generously granting permission to conduct excavations on her property. Special thanks to the original crafters of the earspools, whose artistic contributions to Swift Creek culture still fascinate us centuries later. Finally, thank you to Carl Etheridge for his assistance during the excavation of the feature.

Bibliography

Carter, Jerry. 2015. “Hopewellian Indian Burial Customs and Associated Artifacts.” Central States Archaeological Journal 62(2): 71–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44159738.

Ehrhardt, Kathleen L. 2009. “Copper Working Technologies, Contexts of Use, and Social Complexity in the Eastern Woodlands of Native North America.” Journal of World Prehistory 22 (3): 213–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-009-9020-8.

Keith, Scot. 2020. “The Leake Site: Connecting the Southeast with the Hopewell Heartland.” In Encountering Hopewell in the Twenty-First Century, Ohio and Beyond. The University of Akron Press. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=encountering_hopewell.

Ruhl, Katharine C 1992. “Copper Earspools from Ohio Hopewell Sites.” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 17(1): 46–79, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20708325?seq=16. Accessed 2 Dec. 2025.

Ruhl, Katharine C, and Mark F Seeman. 1998. “The Temporal and Social Implications of Ohio Hopewell Copper Ear Spool Design.” American Antiquity 63 (4): 651–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2694113.

Ruhl, Katherine C. 2005. “Hopewellian Copper Earspools from Eastern North America.” In Gathering Hopewell: The Social, Ritual, and Symbolic Significance of Their Contexts and Distribution, edited by Christopher Carr and D. Troy Case, pp. 696–713. Boston, MA: Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/0-387-27327-1_19#citeas.

Smith, Karen Y., and Vernon James Knight. 2012. “Style in Swift Creek Paddle Art.” Southeastern Archaeology 31(2): 143–56. https://doi.org/10.1179/sea.2012.31.2.002.