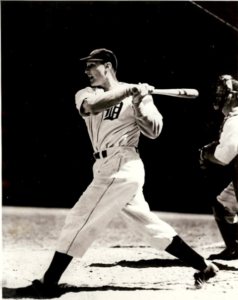

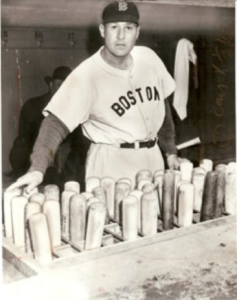

Early in his career on the baseball diamond he was a man without a position. Luckily for him, the power emanating from his bat allowed him to hang around the major leagues long enough to settle into the only position he could play reasonably well. He came from Native American – or, in the common language of the day, “Indian” – ancestry, although that heritage was always more important to the press than it was to him. In August 1937 he broke a home run record set by the immortal Babe Ruth. He had a habit of falling asleep with burning cigarettes in his hand, setting many a hotel room on fire (or so they say). Finally, he had a fondness for alcohol that ultimately contributed to an early departure from the major league scene. Thus summarizes what most fans and historians of the game know about Rudy York.

The fact is, however, Rudy York had a solid major league career. From 1937 through 1947, no one in the major leagues had more home runs, runs-batted-in or total bases than Rudy York, albeit because Rudy was one of the few stars who managed to avoid military service during the war. He had little formal education and grew up in the small mill towns of rural northwest Georgia where so many young people were naturally drawn into the same blue-collar existence as their parents, working in the mills for meager wages. Rudy’s baseball skills allowed him to rise above the mill and enjoy, at least for a few years, widespread public recognition and financial comfort. The recognition and, certainly, the financial comfort diminished considerably after Rudy’s baseball career was over. A close observer of his career can’t help but come to conclusion that, while he had a fine stay in “the show,” he could have accomplished more.

Early Childhood

Preston Rudolph York[i] was born in Ragland, Alabama on August 17, 1913. He was the third of five surviving children of Arthur and Beulah (Locklear) York. Family history states that Beulah’s grandmother on her mother’s side, Elizabeth (Meddows) Barrett, was a full-blooded Cherokee. Although he was born in Alabama, his parents and their respective families had deep roots in the rural communities of northwest Georgia. The family moved to Ragland just prior to Rudy’s birth and returned to Georgia while Rudy was still quite young. Unfortunately, Arthur, who at various times was described as a farm laborer and/or carpenter, was an unreliable husband and father who often wandered in and out of the family structure.

The address on Arthur’s World War I draft registration card indicates he was back in the Aragon, Georgia area by 1917. He entered the Army in the fall of 1917 and was discharged five months later. Beulah and the four children were living at a different address in Aragon by the time of the 1920 census (the fifth child, Lavis, would not be born until later); Arthur is not listed with the family in the census and a notation identifies Beulah as the head of the household[ii]. Beulah was supporting her family with a job as a spinner in the Aragon mill. According to the census records, Beulah’s mother, Nannie, lived next door. The birth of Rudy’s youngest sibling, Lavis[iii], in 1921 is one of the few pieces of evidence that Arthur was maintaining any contact with the family at all. Years later, Rudy told Furman Bisher that his father had deserted the family completely by the time he was a teenager. Court records indicate there was a divorce that was apparently finalized in 1927.

Anecdotal evidence suggests Rudy developed a liking for baseball at a young age. According to Rudy’s son, Joe, “…when daddy was growing up, he had an aunt who could sew a cover on a ball, so they took socks and unwove them – wool socks – wrapped them around a little hard ball, and she was able to sew that. How well it was, I don’t know. That was his first experience with a baseball…. They didn’t have bats. They used broomsticks. They just didn’t have the equipment.”

Atco

In 1903, the American Textile Company built a factory on the western outskirts of Cartersville, Georgia. In order to attract a stable base of employees, the company also established a village around the factory. The village, known as Atco, was owned and operated by the company and eventually included several hundred modest houses which were rented to the employees, as well as a grocery store, a church, a schoolhouse, a laundry, a community center and swimming pool, and its own power plant. The factory processed cotton into thread and other products for a number of different textile applications.

Beulah York moved her family to the Atco community in the late 1920s. Census records from 1930 indicate the family was living in the village by that time; Rudy’ older brother Buddy and Buddy’s wife, Ruby, worked in the factory while Beulah helped to make ends meet by taking in several boarders. Atco, like most other mill villages of the time, had its own baseball club that played against mill teams in other nearby towns including Cedartown, Rockmart and Rome, Georgia. As in most mill towns, baseball was a popular source of entertainment. “We’re talking about a time before TV….Not too many people had automobiles out there….So, most everything – most everybody’s life – was right there in Atco….a baseball game was a big deal.”[v]

Rudy’s road to professional baseball began in Atco. Rudy worked in the factory as a “doffer,” but Joe York later commented “I was told they pretty much hired Daddy not just as a mill worker but as a ball player.”[vi] The earliest documented evidence of Rudy playing for Atco is found in the Rome News-Tribune on April 23, 1929, when his name appeared in the box score for a game in Atco the previous day against a team from Shannon, Georgia. Rudy played shortstop and batted ninth, going 0 for 3. Earlier newspaper accounts from both Rome and Cartersville, going back to 1925, make no mention of Rudy. The Goodyear Rubber Company purchased the Atco[vii] plant in June of 1929, and the baseball team played a schedule of “league” games against other Goodyear plants in the nearby towns of Rockmart and Cedartown, and Gadsden, Alabama, in addition to its non-league schedule against other traditional rivals Rome area. By 1930 he was a blossoming star amongst the other players. In April 1930, the Bartow Tribune-News noted “…York is a sensational shortstop and a clever hitter…”[viii] and, in October of that year, “…Rudy has proved to the public that he loves the game called baseball. He is a good hitter and fielder and has more home runs to his credit than any other player in the Goodyear loop.”[ix]

In 1931, Atco, along with many of its traditional rivals including the Goodyear teams from Cedartown and Rockmart, entered into a more formal league structure when they created the Northwest Georgia Textile League. Rudy continued to prove his superior skills against older players, as noted in the Tribune-News: “York’s batting average is well up with the best of the heavy hitters in the league. He manages to hit nice long ones in practically every game…”[x] and, at midseason, “York’s record is outstanding. Out of forty-eight times at bat, he hit six singles, eleven doubles, two triples and six home runs. His average is .520.”[xi] He finished the season as the league’s home run champion and as a married man. He and Violet Dupree, an Atco girl, married on June 30, 1931[xii].

Rudy continued to showcase his talents in 1932, although by that time he had been shifted to centerfield. Rudy was inexplicably absent from the Atco lineup for a several games in late June and early July of that year. A number of stories published in later years claimed Rudy had a tryout with a club[xiii] in Organized Ball sometime before 1933, but it is not clear that this is why he was absent from Atco’s lineup during this time. Rudy ultimately led the Supertwisters to an outstanding second-half record, however, and they defeated the Goodyear team from Cedartown in the playoffs for that season’s championship. By season’s end, Rudy and Violet also had welcomed their first child, Mary Jane, into the world.

ATCO Supertwisters, York standing second from right with glove on shoulder of teammate.

1933: Have Bat, Will Travel

1933 was a watershed year for Rudy. He moved to third base for the Atco nine, and the Tribune-News continued to comment on his emerging skills. While noting Rudy was erratic at times and “…easily excitable at the crucial moments…”[xiv] Tribune-News Sports Editor Horace Crowe wrote of Rudy:

“… (he) seems to be headed for another great year….(he) is still quite a young man and should he continue to improve as he has in the past performances, he should go up in the game. At present though he has room for improvement, not having the proper hold of himself that the veteran ballplayer must have.”[xv]

After two weekends of league play, Rudy’s name disappeared from the Atco box scores and the Tribune-News announced he had received a tryout with the Knoxville Smokies of the Southern Association. As Rudy left to join the Smokies, Crowe wrote “…York has been clouting the apple well over .500…and has been playing a great game at third base. He is noted all over the Textile league for his wonderful throwing arm.”[xvi]

Professional Debut

The Knoxville club got off to a horrendous start in 1933. Having suffered through a 1-7 home stand at the end of April and with an overall record of 4-13, Smokies owner Bob Allen had already begun making wholesale roster changes in an effort to put a respectable club on the field. The Knoxville Journal sports writer Bob Murphy noted on May 1 that Rudy – a “young kid” – was slated to replace Frank Waddey in left field until more help could be found. Murphy apparently held out little hope that Rudy would make good, commenting that he “…won’t get far.”[xvii]

Rudy made his debut in Organized Baseball that day in Memphis, playing left field and going 1 for 4 with a single in an 11-1 loss to the Chicks. His hometown was proud; the Tribune-News on May 4 spread the word of Rudy’s debut

“Many hearts in ATCO were made glad last Monday morning when it was announced that Rudolph York, erstwhile and deserving ATCO boy, was placed in left field on the Knoxville Southern League team to play that position until further notice. York was called in by Knoxville some three weeks ago and evidently he is making the grade, as his ‘tryout’ contract has expired and he is still with them.”[xviii]

Unfortunately, what the paper’s editors didn’t know as they went to press that morning was that Rudy’s tenure with Knoxville was already over. He played his last game for the Smokies the previous night; Knoxville dropped all three games of the series to the league leading Chicks while Rudy went just 1 for 10 in the three games. Rudy was released and he returned to Atco’s lineup in mid-May, settling in at first base upon his return. By late May he disappeared again, having joined the LaGrange Troopers of the Georgia State League, an independent league unaffiliated with Organized Baseball. Just a few short days after he joined the team, the franchise was shifted to Albany, Georgia and re-dubbed the “Indians”. Rudy was installed as the regular third baseman after an injury to another player. In 1991, Marshall Johnson, who played and roomed with Rudy in Albany, remembered Rudy’s ability to hit the long ball:

“… (On) June 17, we played in Barnesville. As we entered the ballpark we were all amazed at the distance of the 10 foot high centerfield fence from home plate. We laughed and joked about it and agreed that nobody could hit a baseball over that fence 500 feet away. Needless to say, Rudy York did hit a home run over that fence. It was the farthest hit ball I have ever seen.”[xix]

Mr. Johnson also noted that Rudy made an appearance as a relief pitcher in that same game against Barnesville. He went on to describe Rudy as

“…loud and boisterous, and (he) spoke poor English, due no doubt to his poor education…. But Rudy York had a heart of gold. He was kind and considerate and he had an outgoing, warm personality. On the ball diamond he was talking all the time, giving encouragement to his fellow players, and keeping moral (sic) high.”[xx]

Rudy, who was erroneously described by the Albany paper as an “ex-college star” on the eve of the Indians’ debut in Albany, provided the desired firepower at the plate but his fielding at third base was less than stellar. He played with Albany for a little over three weeks; Rudy and two other teammates abruptly left the team on June 24 while in Macon. It is not clear why Rudy and the others abandoned the Indians. It is possible there were financial issues; the Indians were taken over by the league in July when the Albany owners could no longer shoulder the financial burden of operating the team. There was some conjecture that Rudy and his teammates intended to sign with another team in the league, but the league president quickly forbid that possibility. Evidently, Rudy gave no prior hint of his intentions to leave the Indians, and he soon returned to familiar grounds.

Rudy was back in the Atco lineup on Sunday, June 25 but once again he would not stay long. Detroit scout Eddie Goosetree had been on Rudy’s trail since early that spring; he had shown up in Atco in May with the intention of signing Rudy for the Detroit Tigers only to discover Rudy was already in Knoxville. Goosetree had a chance to observe teams in the Georgia State League during Rudy’s time with Albany; maybe Rudy left the Indians knowing that Goosetree was likely to offer him an opportunity to sign with the Tigers. Whatever the chain of events, the Tiger scout finally got his man the first week of July. Rudy was signed and sent to the Shreveport Sports of the Class C Dixie League. Oddly enough, when announcing the signing, The Sporting News described Rudy as a “pitcher-fielder.”[xxi] Only two instances could be found of Rudy ever taking the mound prior to his signing by the Tigers. He made one relief appearance with Atco in 1931, and the other was the relief appearance in June 1933 while with Albany. In both cases, he was inserted in a “mop-up” role and was not effective.

Rudy played twelve games at second base for the Shreveport Sports before being removed from the roster on July 27, apparently because of defensive weaknesses. Official records credit him with a batting average of .354 and his first professional home run. Oddly, an examination of multiple box scores and game accounts for each of his twelve games does not reveal any mention of that home run.

Upon leaving Shreveport, Rudy reported to the Beaumont Exporters of the Class A Texas League. On July 31, his first day with the club, Rudy[xxii] was inserted at catcher with two outs in the bottom of the eighth inning when Beaumont’s regular catcher, George Susce, suffered a broken collarbone in a collision at home plate. This appearance is the earliest documented occurrence of Rudy playing behind the plate. Overall, Rudy received little playing time at Beaumont; he made a few appearances at third base and in the outfield and batted just .189 in thirty-seven official at-bats. His most memorable appearance with Beaumont that year may have been the game of August 21. Already losing by a score of 12 – 2 with two outs in the bottom of the third inning in a game in Oklahoma City, Rudy was called off the bench to relieve starting pitcher Jake Wade. Rudy pitched the rest of the game, giving up five runs, all earned, on two hits, ten bases on balls and one hit batsman.

Rudy’s one-out experience as a catcher in 1933 would turn into a six year, on-again, off-again experiment in human torture for Rudy and the Tiger organization. Rudy rejoined the Exporters for the 1934 season and from the beginning of spring training was described as a promising catching prospect who was expected to add some much needed power to the Beaumont lineup. Describing one workout a couple of days into spring training, the Beaumont Journal noted:

“Then came the big ‘game’ of the day, a ‘one-eyed cat’ move-up scuffle….as usual, Rudy York, the Georgia Bludgeoner, sparkled with his stick work. Rudy rammed out hit after hit and twice sent balls over the pailings just a few inches foul. The Georgia boy is far ahead of the others in camp, having worked out several weeks at his home in Atco before reporting here.”[xxiii]

As the season was getting ready to begin, the Journal noted:

“To casual observers, it looks like York is No. 1 man on the Exporters’ receiving staff… (he) has a powerful arm; by far, the best arm in the Exporter camp. He can hit a dime at 100 feet….not only can Rudy throw, but he is the hardest hitter in camp as well…He’s a real find and a real catcher, and Jack Zeller, Detroit scout, said he wouldn’t take $50,000 for him right now.”[xxiv]

Rudy was slated to share a significant part of the catching duties with Mike Tresh, but things quickly unraveled. Rudy got off to a slow start at the plate and exhibited none of the power that had been expected of him. In early May Beaumont sent Rudy to the Fort Worth Panthers – another Texas League team – “on loan” with the understanding that Beaumont would not recall him before the end of the season unless Fort Worth was willing to return Rudy to Beaumont earlier. Rudy started out as the Cats’ primary catcher, but by the end of May it was apparent his catching skills were suspect. Instead of relegating him to the bench, Cats manager Del Pratt moved him to right field and Rudy’s bat began to come alive as his average rose steadily and his power numbers began to soar. Describing a 11-run rally in the top of the 7th inning in a game at Oklahoma City on May 31, the Journal noted “Chief York started the seventh inning rally with one of the longest home runs ever hit in the Indian Park.”[xxv] Rudy hit a total of eighteen home runs during the months of June and July and moved to the front of the league’s home run race. Unfortunately the Cats were a bad ball club and Rudy’s production with the stick did little to improve Fort Worth’s chances of making the league playoffs. On August 10, with Fort Worth out of contention and Beaumont fighting to qualify for the playoffs, the Cats agreed to return Rudy to the Exporters for the remainder of the season. That decision created a firestorm in the Texas League and paved the way for Rudy’s major league debut.

When Rudy’s recall by Beaumont was announced, other teams objected to the transfer on the grounds that the league had a rule prohibiting the sale or trading of players between teams in the league after August 1 in order to prevent teams from acting in concert to affect the outcome of the pennant race. Beaumont argued the rule did not apply to Rudy’s situation since he had only been “loaned out” to the Cats and was simply being returned to the Beaumont roster. League president J. Alvin Gardner ruled that while Beaumont had every right to recall Rudy, he would not be eligible to play in any of the Exporters’ remaining games.[xxvi] Rudy’s season appeared to be over a month earlier than expected after hitting .332 with 26 home runs and 75 RBI for Beaumont and Fort Worth. (Beaumont eventually missed out on the playoffs.) Then, to his great surprise and delight, on August 16 – the day before his twenty-first birthday – Rudy received word to report to the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers, fighting for a pennant of their own, decided to bring Rudy up to the major leagues with the hope that he might provide some power off the bench. Writing to Ed Sharpe, former Atco manager, Rudy said “This is the happiest moment of my life!”[xxvii] Rudy spent his twenty-first birthday riding the train to Detroit where he briefly met with the press at Tiger Stadium before traveling on to join the team in Boston. He told the Detroit press “It sure is surprising to be greeted like this….Three days ago I had no idea I would see this place until next spring, and it was quite a surprise when the Tigers sent for me.”[xxviii] The press wasted no time playing up Rudy’s Native American heritage, introducing him as the “Cherokee home run king”: “York has been widely heralded as an Indian. In the south they called him ‘Chief’ and took his picture wearing head feathers and swinging a tomahawk…when he played in Tulsa or Oklahoma City, the braves from miles around came to see him perform.”[xxix] Rudy’s own reaction to the interest in his background is proof that the press paid more attention to it than Rudy ever did. Noting the extent of his Native American ancestry was “greatly exaggerated” Rudy went on to say “There is some Cherokee blood in our family, but it goes a long way back. I really never tried to trace it and don’t know much about it. I suppose I’ve got about as much Indian blood as Jack Dempsey.”[xxx]

The Detroit papers informed their readers that scouts and others familiar with Rudy’s performance in the Texas League were very high on him. “York hits the ball as hard as Rogers Hornsby ever did. His home runs are not of the Ruthian variety, long driven flies, but sizzle off the walls or clear the fences on a line.”[xxxi] Fort Worth manager Del Pratt noted that “York is as good right now as Heinie Manush was when he broke into the majors.”[xxxii] Sam Greene of the Detroit News wrote “Scouts covering the Texas territory say that York’s record reflects the work of a natural hitter, of a man who looked better than Joe Medwick of the Cardinals, Henry Greenberg of (the) Tigers and Zeke Bonura of the White Sox did when they were breaking down the fences of the Lone Star circuit.”[xxxiii]

Rudy made his major league debut as a pinch-hitter on August 22, striking out against Earl Whitehill of the Senators. Rudy did not play again until the final week of the season after the Tigers had wrapped up the American League pennant. Some reports suggest that Rudy, already a big man, put on weight during his period of inactivity with Detroit and that manager Mickey Cochrane was not impressed with his catching skills. At the end of the season, Rudy was reassigned to the Beaumont roster.

Rudy went to spring training with the Beaumont club in 1935. The Exporters were still determined to drive a square peg into a round hole. According to the Beaumont Journal, as the team headed into spring training, “…Exporter scouts believe that York’s place is behind the platter, and he is going to be given every opportunity to show his stuff in mask and protector…”[xxxiv] and, on the eve of the opening game of the season,

“Rudy is considered one of the greatest catching prospects in baseball.…(he) throws a ball like a 30-30….is rapidly rounding into a heads-up catcher, though his work behind the platter has been comparatively short….As Rudy goes this year, so will the Exporters, and lots is expected of the big fellow.”[xxxv]

Rudy began the season as the Exporter’s main catcher, with manager Dutch Lorbeer providing occasional relief. The Exporters got off to a hot start, winning their first five games, but by the end of May were struggling to stay in the upper division of the league’s standings. Rudy, who batted well over .300 during the first three weeks of the season, saw his average drop to .279 by the end of May and he was struggling behind the plate as well, although little was said in the local paper about his defensive miscues. On May 30, Lorbeer moved Rudy to first base to replace George Archie, who also was struggling, and installed himself as the Exporters’ primary catcher. Rudy received a number of compliments on his play at first base in his first few games there, and by June 5th the Journal was reporting that the Exporters planned to leave Rudy at first. The team even asked the Tigers’ Hank Greenberg to send one of his used first baseman mitts to Rudy.

Rudy was able to relax after his move to first base and he began a hitting barrage that quickly moved him to the front of the home run race, while his average slowly began moving back towards the .300 mark. The team’s overall performance was slower to come around, but by the beginning of August the Exporters had worked their way back to the top of the Texas League’s standings. They could not fight off the Oklahoma City Indians, however, and finished second by four games. In the league playoffs Beaumont beat third place Galveston, three games to two, in the first round after dropping the first two games of the series. In the championship series, Oklahoma City reinforced its standing as the best team in the league that year by defeating Beaumont four games to one. For the season, Rudy hit .301 and led the league in home runs (32), runs-batted-in (117) and total bases (198) and was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player for his efforts.

Although Rudy was destined to ply his trade for the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association in 1936, his assignment to the Brewers did not come without some spring training intrigue. Rudy’s MVP season in Beaumont once again caught the attention of the Detroit brass and he was invited to train with the Tigers in Lakeland, Florida that spring. Cochrane, who remembered Rudy as a somewhat slow-footed, not-too-promising catcher, was surprised and pleased to find Rudy in excellent physical condition; Charles Ward noted that Rudy “…is built on the lines of a battleship….”[xxxvi] The fact that he had been converted to a first baseman served the Tigers’ immediate needs as well. The start of spring training found first baseman Hank Greenberg in a contract squabble with the Tigers front office. Greenberg had led the Tigers to the 1935 AL pennant and was voted the league’s MVP. He was fully recovered from the broken wrist he suffered in Game 2 of the 1935 World Series and expected to be rewarded appropriately for his fine 1935 season. While Hank wiled away his time in New York waiting for the Tigers to improve their offer, Rudy put on powerful performances early in camp while playing first base in Greenberg’s stead, and the Tigers made sure the press knew how happy they were with Rudy’s performance throughout the spring schedule. After just the first intra-squad game, Charles Ward noted:

“This York person has proved himself quite a powerhouse, even when compared to the hard-hitting Hank Greenberg. He seems able to hit a ball no matter where it is placed just so long as it comes near the plate. And he has the power to give the ball wings once he gets hold of it….Despite Greenberg’s great record…York may prove to be a distinct threat to him before the next season is over….(he) has gotten over the stage fright that afflicted him when he was a member of the team two years ago….it must be said that he looks like a better ballplayer than Greenberg did the year he came up. However, Hank developed fast.”[xxxvii]

Two weeks into spring training, Associated Press writer Paul Mickelson proclaimed “…Cochrane is so impressed with another rookie, Rudolph York from Beaumont, that scribes with the team expect him to let him play the opening game if for no other reason than to show big Hank that York is a qualified replacement.”[xxxviii] A few days later, the Tigers received some help in their public efforts to put the squeeze on Greenberg. AL President William Harridge singled out Rudy and Joe DiMaggio as the most promising rookies in the league that year and, when asked to choose between them “…his nod – very slight – goes to the Detroit youngster.” Harridge continued: “In the Tiger camp, they weren’t saying a thing about holdout Hank Greenberg…York looks like he’ll deliver in great style. He’s a powerful hitter and fields in major league manner.”[xxxix]

The public relations campaign was effective, if unnecessary. The next day it was announced Greenberg had decided to travel to Florida to work out his contract with the Tigers. The Detroit press never took Hank’s holdout or the Tigers’ promotion of York too seriously; as W.W. Edgar wrote on March 10 “…not by the wildest stretch of the imagination can one picture him (Greenberg) sitting on the sidelines. Neither can one picture Rudy York taking over his job. Greenberg will be back at first base when the season opens. Make no mistake about that.”[xl] While Mickey Cochrane would have loved to have Rudy’s bat in the lineup every day, the fact was there was no room for him on the roster. A place in the outfield was the only possible alternative to first base, but Detroit was already loaded with outfielders for 1936, including Goose Goslin, Pete Fox, Gerald Walker, Jo Jo White and the newly signed Al Simmons. Rudy himself knew he had little chance of displacing Hank at first base. When asked how he expected to win a place on the roster, Rudy remarked that he didn’t “expect” anything; Mickey Cochrane got paid to make those decisions. But if he had to make the decision, Rudy would move Greenberg to left field, not because he felt he was better than Hank at first, but rather because Hank would make a better outfielder than Rudy. “I don’t think much of my chances in the outfield.”[xli] Rudy was optioned to Milwaukee the first week of April.

The Brewers, managed by former major league hurler Al Sothoron, had disappointed Milwaukee fans in 1935 but were expected to be a strong contender for the American Association title in 1936. The Brewers had a solid lineup with Rudy, second baseman Eddie Hope, shortstop “Wimpy” Wilburn and third baseman Lin Storti manning the infield; local favorites Chet Laabs and Ted Gullic patrolled the outer gardens along with Chet Morgan. Centerfielder Frenchy Uhalt, purchased from Oakland in mid-May after Gullic went down with a broken ankle, solidified the outfield and provided a good bat and much needed speed at the top of the lineup. George Detore and Bill Brenzel shared the catching chores for most of the year. The pitching staff was led by Joe Heving, Clyde Hatter, Luke Hamlin and Tot Pressnell, a young knuckleball specialist who would surprise everyone by winning nineteen games over the course of the year.

Sothoron was quite pleased to have York on his squad. Anticipating Rudy’s assignment to Milwaukee before the Greenberg drama began to play out in full, Sothoron noted “Rudy…will be one of the most popular players we’ll have in Milwaukee this year. York, who is part Indian, showed me he is the kind of slugger our town will rave about.”[xlii] Rudy also was singled out for his enthusiasm and leadership on the field as well. On the eve of opening day, Sam Levy of the Milwaukee Journal wrote “…York…is the spark plug of the entire club. Aggressiveness and fight are his motto and his steady patter around first base already has had a noticeable effect on the rest of the players.”[xliii] Two weeks into the season, Brewer owner Heinie Bendinger even noted “…you can hear that fellow York all the time.”[xliv]

Rudy and the Brewers got off to slow starts on their bone-chilling, season-opening road trip through the league’s eastern loop, which included stops in Louisville, Indianapolis, Columbus and Toledo. They finally arrived in Milwaukee at the end of April playing just well enough to stay in the upper division of the standings and hoping the cozy confines of Borchert Field would awaken their bats from an early season slumber.

Before the home schedule could get underway, however, the Brewers were temporarily jolted by the possibility they would lose Rudy to the Tigers after all. On April 29, Hank Greenberg broke his right wrist, the same arm that had been injured during the World Series the previous fall. Given the Tigers’ public reaction to Rudy’s play in spring training it was natural to assume the Tigers would recall him from Milwaukee to fill in for their injured star. This option apparently received scant consideration, however, as reflected in a good-natured commentary by “Iffy the Dopester” on Cochrane’s leadership skills during a crisis:

“…Mickey is a first class fighting man. He showed this the moment Homer Hank the big Greenberg boy cracked that wrist of his again….Gone was all this foolishness about that first baseman York, or Nork or Fork who would play so much better than Hank that the Bronx Bomber would never be missed. Mickey’s press agent kissed him into a world of trouble with that baloney. When disaster smote him Mickey reverted to type, the cool, quick thinking leader….”[xlv]

Cochrane very quickly decided to go with an experienced first sacker, trading pitcher Elon Hogsett to the Browns for Jack Burns.[xlvi] Milwaukee fans and manager Sothoron certainly weren’t complaining. As Sothoron told the Journal: “…Everybody on the club realizes Rudy’s value to the team. If we had lost the Chief on the eve of our opening game with Louisville…it might have affected the entire club.”[xlvii] Rudy stayed in Milwaukee, and the initial home stand provided the spark that Sothoron, the players and the fans had hoped for. By the end of May, the Brewers had moved into the league lead by one-half games over Kansas City. Rudy led the Brewer regulars with a .341 average and was tied with Chet Laabs for the team lead with forty-two runs driven home. There was a spirited race for the team home run lead as well; Laabs led with fourteen round-trippers, while Rudy and Lin Storti were tied with ten apiece.

The Brewers still held the league lead at the halfway point in the season which entitled them to be the host team for the American Association All-Star game. Rudy was named to the All-Star team, although he actually played for the Brewers against the All-Stars from the other teams. The All-Stars defeated the Brewers, 9-5, in a game that started at 2:30 in the afternoon in a suffocating heat and thankfully lasted just one hour and fifty-two minutes. Rudy went 2-4 with a double.

After the All-Star game, Milwaukee and St. Paul would battle for the league lead until the Brewers, thanks to a 22-7 home stand in August, built an 11 ½ game lead. Rudy went over the 100 RBI mark on August 1, and other teams were starting to show interest in him. Sam Levy of the Journal noted that the Cubs were particularly interested in acquiring York, but the Tigers had no plans to trade him and would keep Rudy in Detroit in 1937 as insurance against further injury to Greenberg. Again, speaking to Rudy’s aggressiveness and leadership, Levy wrote “…none of the players who are farmed out by the Detroit club possesses the vim, vigor and aggressiveness of Chief York. The big first sacker, the spark plug of the Brewer machine, fights just as hard when his club shows a large deficit in the scoring column as he does when it is in position to coast along….”[xlviii] Levy’s high opinion of Rudy was shared by others around the league. Minneapolis manager Donie Bush told Levy “…I’ve had a high opinion of his ability ever since I saw him the first time we played your club in Florida. Any big fellow who moves around as fast as York does and has that long distance hitting power is my ideal.”[xlix]

Rudy and the Brewers went into a mild slump after their impressive August home stand and their lead in the standings shrunk to 6 ½ games by September 2nd. The season was drawing quickly to a close, however, and the Brewers clinched the pennant – their first since 1914 – with a doubleheader sweep over Minneapolis on September 3rd. They closed out the regular season on the seventh by dropping a Labor Day doubleheader in Kansas City, but received a huge welcome home the next morning in Milwaukee. Commenting on the excitement surrounding the homecoming, the Journal noted that “Rudy York, the big chief, rode with the driver on one of the red fire trucks and appeared to get an immense kick out of the welcome.” [l]

The Brewers’ end-of-season slump was quickly forgotten once the playoffs began. Led by the big bats of Rudy and Chet Laabs, along with solid pitching from each of the four starters, the Brewers swept the KC Blues, four games to none, in the first round. Rudy went 6 for 16 with four runs driven in, and he and Laabs both hit two home runs in the series. Solid hitting performances up and down the lineup allowed the Brewers to breeze to the American Association championship over the Indianapolis Indians, 4 games to 1, in the final playoff series. Milwaukee hit .305 as a team in the series; Rudy and Laabs each drove in five runs. Luke Hamlin got credit for the wins in Game 1 as well as the clincher.

Their win over Indianapolis entitled Milwaukee to face Ray Schalk’s Buffalo Bisons, champions of the International League, in the Little World Series. The first three games were played in Milwaukee, a huge advantage that the Brewers capitalized on by sweeping all three games. Tot Pressnell won each of the first two games, pitching in relief of Joe Heving in the first game and Clyde Hatter in game two. The second game was a cliffhanger. Lin Storti and Ted Gullic both hit a pair of homers in the game, with Storti’s second circuit clout winning the game for Pressnell and the Brewers in the bottom of the eleventh inning.

Back in their home park, Buffalo won the fourth game of the series but Pressnell, this time in a starting role, picked up his third victory in game five and closed out the series on October 1 with an 8-3 win. Rudy’s bat was relatively quiet against Buffalo, as he knocked in just three runs in the series.

Thanks to the Brewers success that year, Milwaukee drew 250,000 fans in 1936, more than doubling the attendance from the previous year. Rudy finished the regular season with a team-leading .334 average (including 207 hits), and he was second on the team in homers (37) and runs-batted-in (148), finishing just behind Laabs in both categories. He was fifth in the league in slugging percentage (.620). Among his many accolades, Rudy won his second straight MVP award, edging out St. Paul pitcher Lou Fette, who won 25 games for the Saints that year. He was also a fan favorite, winning their vote as team MVP in a poll sponsored by the Milwaukee Junior Chamber of Commerce. According to the Journal, Rudy was even offered a one-week engagement at a local vaudeville theater, along with Laabs and Frenchy Uhalt, although there is no evidence Rudy cashed in on that offer.

The local press also expressed tremendous pride in the accomplishments of Rudy and his teammates. Sports editor R. G. Lynch commented:

“…it may be years before Milwaukee has a baseball team like the 1936 outfit…. How often do you find on one team the niftiest double play combination…the fanciest fielding first baseman…and a couple of young sluggers headed for the major leagues?… It’s a pleasure to watch Rudy York operate around first base. He’s a moose but amazingly agile for a big man, and the way he waves that leather claw of his through the air and picks off the ball never fails to cause comment among the crowd….”[li]

Sam Levy, the Brewers’ beat writer from the Journal, noted at the end of the season:

“Laabs and York! How we’ll miss them dynamite twins in 1937. Two men of iron! Think of it – neither missed an inning throughout the trying 154-game schedule. There were times when Chief suffered hurts, minor hurts to him, but he never gave them a thought. Most players under similar circumstances would have ‘jaked’ – sought a rest.”[lii]

Perhaps Rudy’s most significant bonus arrived near the end of October when Violet gave birth to their second child (and only son), Joe Wilburn York. Joe’s middle name was selected as a tribute to Rudy’s Milwaukee teammate, Chet “Wimpy” Wilburn.

Rudy’s 1936 performance in Milwaukee virtually assured him of a place on Detroit’s roster in 1937. Offensively, Rudy had nothing left to prove as a minor leaguer. He was ready for the big leagues, and Mickey Cochrane was anxious to add Rudy’s bat to the Tiger lineup in 1937. The only problem was where Rudy would play in the field. Hank Greenberg already was well established at first base and although Mickey Cochrane suggested that Greenberg might be moved to the outfield to make way for Rudy at first, Hank was having no part of it. “The only way I’ll play the outfield is if Rudy York is a better first baseman than I am. I’m a first baseman by inclination…. I’ll play first base unless Rudy can beat me out. Everything I hear is that he is quite a first baseman, the best the American Association ever turned out.”[liii]

For his part, Rudy much preferred to play first base, but he knew he had no better chance of displacing Greenberg in 1937 than he’d had in 1936. “If I don’t play first base for the Tigers I’ll play for somebody else. They can send me out just so often and then they’ll have to do something about it. I’ll play first base for some big league team and I don’t care much which one it is so long as I get my pay regularly”[liv] he told Charles Ward, and he later admitted to W.W. Edgar: “I’ll give him a battle, but nobody is taking Greenberg’s job away from him yet. That job is his if he’s able to play.”[lv]

Rudy refused to sign the first contract he received in 1937, suggesting that as a two-time minor league MVP he deserved a little better consideration from the parent club. Ward suggested Rudy’s brief holdout might have been designed to put pressure on the Detroit club to “play me or trade me”: “… it is also possible that Rudy’s ‘holdout’ is motivated by Hank Greenberg, and that his demands for money are merely a means to an end. That end would be, of course, a railroad ticket to some major league city other than Detroit.”[lvi] Rudy and the Tiger management settled their differences before spring training started, however.

By the time spring training came around, Mickey Cochrane had abandoned the idea of shifting Greenberg to the outfield, but he was still anxious to find a place for Rudy in the Tigers’ everyday lineup:

“We are going to shift him around until we find a place for him. I’d like to make use of Rudy’s power with the stick…I might send him over to third base and see what he does. If he can play first, Rudy should also be able to play third….and if he doesn’t fit in there, we’ll try him in the outfield. I’d hate to see all that batting power go to waste.”[lvii]

Rudy did, in fact, spend virtually all of his time during spring training at third base. Coach Del Baker spent hours hitting balls to Rudy at third to help him learn the position. Cochrane acknowledged that it would be a tough decision to replace incumbent third baseman Marv Owen with someone as untested as Rudy, but that decision would be hinge to a large extent on the status of the Tigers’ starting pitching. “…(I)f we are going to be weak on the mound, we’ll have to sacrifice our defensive strength for power at the plate. We’ll need all the heavy hitters we can get because it’s a cinch the other fellows are going to get some runs and we’ll just have to try and outscore them.”[lviii] Midway through spring training, H.G. Salsinger noted “Cochrane is much impressed with York’s work at third base. ‘If he makes up his mind that he can play third, he should be a top-notch third-sacker. There’s no question, of course, about his hitting ability. ‘“[lix] Despite Cochrane’s optimism, press accounts of the Tigers’ spring games made frequent mention of Rudy’s problems in the field. As spring training came to a close, Cochrane seemed to change his mind almost every day. At the end of training, Mickey had decided to move Owen back to third base, noting “It is almost a crime to keep those fellows out of regular jobs, but I don’t see how they can get them on our club. On any other club in the majors, both York and Croucher would be stars, and yet here they are the victims of fate that keeps them off a club.”[lx] By the time the Tigers got back to Detroit for the season opener on April 20, Cochrane had changed his mind again. Black Mike conceded:

“Don’t see how I can afford to keep York on the bench. He has shown me so much batting power, which we certainly can use, that it looks like the proper thing to do is to have him in our lineup….his defensive play has not been so bad either. He’s made a couple of wrong moves because of inexperience at that base, but I think he’ll get over that shortly. All he seemingly has to do is tap the ball to hit it out of the park…”[lxi]

Rudy was in the opening day lineup at third base as Eldon Auker out-dueled the Indians’ Mel Harder for a 4-3 victory. Detroit centerfielder Gee Walker hit for the cycle while Rudy singled in two official at-bats. Noting the enthusiasm of the crowd that day, Doc Holst wrote that Rudy and Hank Greenberg were in a tight race for the crowd’s adulation: “York won that contest with Hank by a falsetto shriek of a young girl. It was that close,” and “For the first time since Chief Hogsett left Navin Field the fans had a chance to exercise their knowledge of Indian war cries. They started it when Rudy York came to bat.”[lxii] During the game, however, pitcher Eldon Auker felt it necessary to try and cover for Rudy on two bunt plays, failing to get the runner in both cases. “How well York can play bunted balls remains to be seen. Auker showed no confidence in York’s ability.”[lxiii]

Rudy hit his first major league home run on April 29th against the White Sox’ Earl Whitehill, but by early May his defensive liabilities were too obvious to overlook. In addition to mishandling a grounder in one game in early May, “York also let a pop fly get away from him while the crowd groaned. Rudy misjudged another pop foul, but escaped being charged with an error simply because he misjudged it so badly he couldn’t get his hands on it.”[lxiv] In addition to his difficulty with bunts and pop-ups, Rudy had no range. He couldn’t go to his right or left. The Detroit crowd increasingly expressed its impatience with Rudy’s fielding and those catcalls also affected Rudy at the plate. Owen replaced him soon thereafter and Rudy spent most of the month of May on the Detroit bench.

The Tigers were dealt a severe blow on May 25 when Cochrane was hit in the head by a pitch from the Yankees’ Bump Hadley, effectively ending the future Hall of Famer’s playing career. From a baseball perspective, Cochrane’s loss was one for which the Tigers were ill prepared. Many people think Rudy replaced Cochrane as catcher immediately after the beaning. This, in fact, was not the case; Birdie Tebbetts took over the catching duties after Cochrane was injured. Rudy remained on the bench and was actually sent to AA Toledo in early June, although he was recalled a day later after Owen suffered a broken hand. Even then, however, Rudy could not get back in the lineup right away. Interim manager Cy Perkins[lxv] waited until mid-June, when Detroit left town for an extended road trip, to put Rudy back at third base, thinking that he would have less pressure on him playing away from the glare of the hometown fans.

Rudy’s offensive output improved considerably with his return to the lineup, although his fielding continued to be a problem. He hit 11 HR with 34 RBI between June 16 and July 23, but he also was charged with 6 official errors during that stretch in addition to the balls he couldn’t make a play on that went for base hits. During the game of July 1, “…the White Sox had a hunch that maybe the big Indian at third base (Mr. Rudy York) wasn’t so hot in fielding bunts and so they began bunting toward third. That kind of strategy is not good for a big Indian….”[lxvi] Birdie Tebbetts had to come out from behind the plate to field the bunts put down in Rudy’s direction. Two days later “York missed on four balls today that went for hits. Three of these York-made hits made two runs possible. Driving in four runs in the second inning and scoring another after doubling in the seventh, York finished the day three runs up.”[lxvii] On July 5th he failed to make the play on two routine grounders, both of which led to 2 runs. But Rudy hit a home run to win the game and “…all was forgotten when York hit for the circuit. He left the field, grinning, the hero rather that the villain of the Tiger cast.”[lxviii] A few days later “Averill hit a perfect double play ball to York’s left but York never moved his feet an inch, simply waving his glove hand at the ball as it passed him.”[lxix] His poor fielding once again became too much to bear. Marv Owen was ready to return to the lineup in late July and Del Baker decided to make the switch. Mickey Cochrane returned to his manager’s post a few days later and agreed Rudy was unsuitable at third base. Detroit was still in desperate need of offensive punch in their attempt to gain ground on the league-leading Yankees; after a week on the bench and with Birdie Tebbetts barely batting .200, Cochrane decided to put York behind the plate for the game of August 4 against the Athletics in Philadelphia. York was not anxious to assume the club’s catching duties. He was on record as far back as 1935 that he didn’t like catching because it required “…too much thinking to get any fun out of baseball.”[lxx] But he agreed to do it if Cochrane would leave him there. Cochrane assured York that he would give him every chance in the world to settle in and do well. Rudy responded by breaking a home run record held by the great Babe Ruth.

Rudy hit home runs in four of the first six games in which he appeared behind the plate. By August 19 he had produced 8 homers and 27 RBI for the month, numbers that would have reflected an excellent full-month’s showing for most other players. But Rudy wasn’t through. The first game of a doubleheader on August 22 began a streak of 5 consecutive games in which he hit at least one home run (he hit two in the first game of an August 24 doubleheader), producing 12 more RBI along the way. Heading into the game of August 31 against Washington’s Pete Appleton, Rudy had 16 home runs for the month, just one shy of Ruth’s record of 17 in a calendar month set in September 1927. Rudy came through in a big way that day, hitting two home runs to set a new record and knocking in seven runs, which gave him 50 RBI for the month of August.[lxxi] Doc Holst noted that the 7,000 fans in Navin Field that day didn’t seem to be concerned with the fact that Roxie Lawson had won his 17th game for the Tigers, nor did they get excited about Gehringer’s 3 for 3 day. Instead, “All they saw was that it was York’s day to establish himself as a greater home run hitter than Ruth and the Indian delivered.”[lxxii]

But what about Rudy’s catching? Cochrane was true to his word and left Rudy behind the plate for most of the rest of the 1937 season. Cochrane presented Rudy’s case to the press quite positively during that time, although there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that Rudy was hardly an All-Star catcher. He was charged with nine errors during his time behind the plate in addition to 12 passed balls, while throwing out just 28% of runners attempting to steal against him (the league average for runners caught stealing in 1937 was 38%). Still, Cochrane tried to convince the press he had solved the conundrum of where to play Rudy. After Rudy’s first game behind the plate, Cochrane told the press “That fellow looks all right behind the plate. He seems to know what the business is all about, and he can hit and throw. I think he will make good.”[lxxiii] Just a few days later, with trade rumors swirling around Rudy, Cochrane noted “We could use some pitching strength, I’ll admit, but we’re not letting York go…I haven’t seen any wild pitches get past him. He seems to have found his spot as catcher.”[lxxiv] Members of the Detroit press seemed to buy into story as well. Salsinger wrote:

“Rudy York caught his third consecutive game for Detroit yesterday, and if he continues hitting as he has been in the last three games, he has won himself a job. He may not know as much about catching as Bolton, Hayworth or Tebbetts, but he produces long hits and teams need long hits to win ball games.”[lxxv]

Of a game on August 10 in which Tiger pitcher George Gill suffered from bouts of wildness, Charles Ward commented: “When George went to the mound he proved to the complete satisfaction of the 11,500 witnesses that York can stop wild pitches if he can do no other task that is required of a catcher. Rudy stopped them to the right of him and to the left of him, high and low.” Ward also used the events of the day to point out a problem many new catchers have when first learning to handle a pitching staff and, as an extra bonus, provided a prime example of the lack of sensitivity towards ethnic stereotyping so prevalent during that era. Noting that Gill and Rudy seemed to be having a hard time getting together on signals, Ward said “….Rudy probably was calling the pitches in the Cherokee sign language while George, for all anybody could tell, knew only the Choctaw….Twice while Bonura was being walked, York called time and asked for a pow-wow.”[lxxvi] In mid-August, Cochrane told Sam Greene “He has improved fast in the few games he has been back there. He is not yet fully familiar with the weaknesses of the batters but he is learning. It won’t take him long to iron out the few mechanical flaws he has. I’m sure that he is our best catching prospect for next year. If he fills the bill he will solve our biggest problem, outside of pitching.”[lxxvii]

Offensively, Rudy cooled off a bit during the month of September. He actually spent several days in the hospital with an infected arm, a malady that originated when he accidently trimmed his nails too closely and opened a cut on one of his fingers. He finished the year with a .307 average, 35 HR and 103 RBI, all in just 375 official at-bats. Although the Tigers finished in second place some 13 games behind the Yankees, Rudy’s late home run surge and his race with Hank Greenberg for the club home run title, along with Charley Gehringer’s run at a batting crown and eventual MVP title, kept the turnstiles humming at Navin Field in 1937; the Tigers finished first in the league in attendance, drawing just over 1 million fans. Towards the end of the season, Charles Ward, using Rudy’s rise to prominence after moving behind the plate as an example, noted how perceptions can change so quickly. While Mickey Owens had been the talk of the talented young catchers earlier in the year, “… (York) is now rated as the finest young catching prospect in baseball. Not only that, but he is being acclaimed by critics as the prize rookie of the year”[lxxviii] and, after the season was over, “…you can’t…help but wonder what the Chieftan will do next season when he can play a full string of games.”[lxxix] The Sporting News named Rudy to its All-Rookie Team for 1937.

Rudy York injured from ball to the head in 1938

Detroit 1938-1939

The Tigers’ catching situation would be a constant source of concern for Mickey Cochrane heading into the 1938 season. Tigers owner Walter Briggs denied Cochrane permission to be reinstated as an active player, presumably out of concern for Mickey’s health, eliminating that option behind the plate. Sam Greene noted before spring training ever started that Rudy “…is not a polished receiver… is not yet a dependable thrower. He is not an inspiring partner for a sagging pitcher…. Cochrane will have to do a great deal of work with the Cherokee clouter before he is the kind of maskman required on a pennant winner.”[lxxx] Cochrane indeed worked with York in spring training to try to improve his mechanics; progress was characterized as sufficient if somewhat minimal. Cochrane knew that Birdie Tebbetts was an outstanding catcher and instilled more confidence in the pitching staff than York ever could, but York’s slugging kept him in the number one catching position. His hitting also bought him his first taste of widespread national exposure among the general public when he made the cover of Newsweek magazine with the caption “Rudy York: Greatest slugger since Babe Ruth?”[lxxxi] Cochrane couldn’t justify relegating Rudy’s bat to the bench. Rudy started out the season as the starting catcher, but things went downhill fast. Besides Rudy’s limitations behind the plate, he got off to his typical slow start at the plate. Two weeks into the season, Cochrane installed Tebbetts as catcher and moved Rudy to left field, suggesting this would be his new position. Rudy made an error in his very first game in left field and generally seemed uncomfortable in the outfield. He didn’t stay there long, however; in his second game in the outfield on May 5, Tebbetts got into a fight with the Red Sox’s Ben Chapman, was ejected from the game and suspended several games by the league. Rudy returned to catching duties temporarily during Tebbetts’ forced vacation. Luckily, Rudy’s batting stroke returned at about the same time; he hit nine home runs during the month of May, including three grand slams. He went back to left field upon Tebbetts’ reinstatement and played there the last half of the month, but his poor fielding forced Cochrane to throw up his hands and put him back behind the plate. York spent most of the rest of the season as the Tigers’ primary catcher and his offensive contributions kept the Tigers’ slim pennant hopes alive. At the end of June, Sam Greene noted:

“It is no more than fair to say that York has been the main factor in keeping Detroit within hailing distance of the leaders. Despite flaws in his defense, the Cherokee has been more valuable than any other individual. His long distance clouting has been both a mechanical and a moral force, pounding runs across the plate for the Tigers, giving them hope when behind and often providing the basis of exultation when ahead.”[lxxxii]

The Tigers floundered around the .500 mark for most of the summer, mostly due to poor starting pitching. Rudy missed a week after a severe beaning on July 21 at the hands of Washington’s Monte Weaver. Shortly after Rudy’s return to the lineup, Mickey Cochrane was fired on August 6 with the Tigers mired in fifth place with a record of 47-51. Arch Ward of the Chicago Daily Tribune went as far as to say Rudy and Hank Greenberg were partly responsible for Cochrane’s firing because they often ignored Cochrane’s signals while focusing too much on home runs.[lxxxiii] Del Baker took over the managerial reigns of the club and led the club to a 37-19 record over the remainder of the season to finish in fourth place. The main excitement for the Detroit club during the final stretches revolved around Greenberg’s chase of Ruth’s single season home run record. Ultimately, he fell two short of tying the record with 58 home runs. For the season, Rudy hit .298 with 33 home runs, including a record-tying 4 grand slams[lxxxiv], and 127 RBI.

Press reports in the off-season indicated Del Baker was giving serious consideration to moving Rudy back to the outfield for 1939. The Tigers’ starting pitching had struggled in 1938 and Baker believed Birdie Tebbetts would do a much better job of helping the pitching staff find their rhythm. The Tigers also were high on newcomer Dixie Parsons as a back-up to Tebbetts, making Rudy expendable behind the plate. Baker believed that Rudy had never been given a real chance in the outfield; he had been thrown into the outfield in 1938 during the season without any chance to acclimate himself to the position and expected to perform at the same level as an experienced outfielder. Baker felt that if Rudy could have an entire spring training to learn and practice the position that he would become at least an average outfielder, which would have been perfectly acceptable to the Tigers. The offseason also gave birth to new trade rumors. The most significant rumor had Rudy going to the Athletics for outfielder Bob Johnson and third baseman Bill Werber. Such a trade would fill two holes for the Tigers, but the deal was never consummated. Rudy’s name also was mentioned in a possible multi-player trade with Washington for shortstop Cecil Travis but that rumor also died on the vine.

Baker’s tentative plans to return Rudy to the outfield were derailed prior to spring training by Rudy himself. Rudy notified the Tiger brass that he did not want to move to the outfield. He preferred, instead, to remain a catcher and Del Baker eventually decided to drop the idea of moving Rudy to left field. Heading into the season, however, a consensus finally seems to have emerged that “…York is not a good catcher and … he will not likely ever be a member of the top class of receivers…. (Tebbetts) is a much better catcher than York; better than York probably ever will be.”[lxxxv] York’s refusal to move to the outfield created problems for the team’s outer garden as well. The outfield candidates lacked punch, with the exception of Chet Laabs who couldn’t seem to find the consistency at the plate needed to win a starting job in the outfield. The Tigers were all set with Pete Fox in right field, but Baker was having difficulty finding suitable players for the other two outfield spots from the likes of Laabs, Dixie Walker, Roy Cullenbine, Barney McCoskey, Frank Secory and Les Fleming (himself a converted first baseman forced into the outfield because of Greenberg). Rudy began the season as the starting catcher but soon missed several games due to a relatively minor health problem; he ended up sharing the catching duties with Tebbetts for most of the summer. He missed time in July with a split finger, and then moved to first base in mid-August when a slumping Greenberg was briefly benched and then suffered a pulled muscle in his side shortly after his return to the lineup. Rudy spelled Greenberg at the first sack for much of the last half of August, returning to a platoon situation behind the plate in early September. The Tigers were never in pennant contention in 1939; they finished in fifth place with an 81-73 record. Rudy, his playing time significantly reduced (he had just 329 official at-bats) hit .307 with 20 home runs and 68 RBI. By the end of the year, it was clear that Birdie Tebbetts was slated to become the Tigers’ first string catcher. Detroit was going to have to make a difficult personnel decision of some type if Rudy was going to remain with the club.

There was much speculation early in the offseason as to what that move would be. It was widely reported that the Tigers were open to trading either Greenberg or York, and that Washington was still interested in acquiring either one. The pundits also concluded that Detroit might well part with Greenberg instead of York, in part to rid itself of Hank’s high salary and to avoid the usual haggling with Greenberg on his salary for the following year. The assumption was that the Tigers would ask Hank to take a cut in salary for 1940, a request Greenberg was likely to resist. Now, the Tigers had some ammunition in their salary battle with Greenberg. According to Sam Greene,

“…York has established himself as a long-distance hitter, regardless of the pitching, and this year he proved adequate at first base when called upon to substitute for Greenberg. As a matter of fact, York’s work was a revelation, given the slip-shod performances he had previously given at third base and in the outfield.”[lxxxvi]

Greenberg could be replaced without sacrificing too much either at the plate or in the field; the Tigers might actually be better off if they could fill a hole in their starting rotation or the outfield by trading Greenberg. By the time of the winter meeting in Cincinnati, however, Clark Griffith of the Senators was more interested in York, offering Cecil Travis in return. A trade never materialized. Reports of possible interest in Rudy from the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees also passed without any action being taken. The winter meetings came and went with both Greenberg and York still on the Tigers’ roster. Other rumors coming out of the winter meetings loomed more ominously for the Tigers, however.

During much of 1939, Commissioner Landis, never a fan of the extended network of farm systems that teams had developed over the previous two decades, had been investigating the Tigers’ manipulation of player contracts in their minor league system in years past. By the time of the winter meetings, rumors were rampant that the Commissioner would be announcing his decision soon, and that the Tigers were going to be severely penalized for improper activities.[lxxxvii] Among the rumors was one that said Rudy, among others, was going to be declared a free agent. If that should occur, he would be able to sell his services to any club he liked for whatever amount could be agreed upon. Many speculated that Rudy might be able to get almost $100,000 on the open market; Washington Post baseball columnist Shirley Povich likened Landis to Rudy’s personal Santa Claus, and made a strong argument outlining the reasons why Rudy was likely to wind up in the Yankee fold.[lxxxviii]

The answer to Detroit’s first base dilemma came in late January 1940. The solution no doubt emanated partly from Commissioner Landis’s much-anticipated decision in early January to penalize the Tigers for improper farm team player manipulations. The Commissioner granted free agency to 91 players in the Tigers’ system.[lxxxix] Rudy was not one of those affected by the ruling; evidently the Commissioner did not go back to 1934 when the Tigers shuttled Rudy back and forth between Beaumont and Fort Worth. One of those granted free agency was Benny McCoy, who the Tigers had traded to the Athletics for outfielder Wally Moses during the winter meetings the previous month. Landis’ decision had the effect of negating the trade, and the Tigers needed to find another solution to their long simmering problem of a lack of outfield punch. With spring training staring them in the face, the Tigers announced that Greenberg had acquiesced to the Tigers’ request to try to learn to play the outfield; if he could make the transition successfully, the Tigers could move Rudy to first base and have both of their big guns in their lineup on a regular basis. Greenberg promised to give it his best effort, and it was later revealed that the Tigers gave him a significant increase in salary in return for his willingness to change positions.[xc]

Detroit 1940 – 1945

Having finally shifted Greenberg to left field and installed Rudy at first, the Tigers fielded a very competitive team in 1940. Led by Greenberg, York, Charlie Gehringer and Barney McCoskey at the plate, Bobo Newsom and a rejuvenated Schoolboy Rowe on the mound, the Tigers moved into first place on July 2 and clinched the AL pennant on September 27 with a 2-0 road win over Cleveland. Rudy provided the winning blow in that game, a 4th inning 2-run homer off of Bob Feller, who for years afterwards complained it was a “cheap” wind-blown pop fly that just barely cleared the right field fence. The Indians finished second in the pennant chase by just 1 game. For the season, Rudy hit .316 with 33 HR and 134 RBI and did not miss a single game. The Tigers dropped the World Series to Cincinnati in 7 games, however. Rudy finished eighth in the MVP voting. (Hank Greenberg won the MVP award in 1940.)

One wonders what the Tigers might have accomplished from 1937 – 1939 if the they had come to the realization earlier that first base was the only viable option for Rudy. Besides helping lead Detroit to pennants in 1940 and 1945, after taking over at first base he was in the lineup almost every day during his last for 6 years with the Tigers. In fact, from May 24, 1942 through July 30, 1942, Rudy held the active “iron man” title in the major leagues, playing in 422 consecutive games before the streak ended on July 31.[xci] Rudy played in at least 150 games each year from 1940 through 1947. He was never drafted into military service (he was rejected in April 1944 because of a “loose knee”) and was one of only 13 players in all of the majors to start each opening day game between 1941 and 1946.[xcii] While his talent as a defensive first baseman is open to debate, on outward appearances his performance was certainly more than adequate. Fans marveled at his one-handed grabs of throws from the other infielders, and he routinely was among the league leaders in putouts, assists and double plays as a first baseman. In his years with the Tigers, his fielding percentage as a first baseman typically hovered around the .990 mark.[xciii]

Back home in Cartersville, Rudy and Violet’s last child, Blanche, was born in September 1940. More than 60 years later she could still recall the times when some of her father’s teammates, most notably Hank Greenberg and Dizzy Trout, would stop by the house on the way to spring training. Recalling one time when Greenberg spent the night with them, Blanche said “He slept in Joe’s bed. The next morning I knocked on the bedroom door and opened the door to tell him breakfast was ready. There were these two long legs dangling off my brother’s bed. I closed the door as fast as I could. It was the funniest thing I had ever seen.”[xciv] She also remembered her mother

“…wouldn’t let Daddy whip the children. She was afraid he would hurt us because his hands were so big. One time, when I was 8 or 9, I left the yard when I wasn’t supposed to and went down to a girlfriend’s house a couple of houses away. I didn’t go home when mother first called; I started home after she called a second time, and saw Daddy heading towards me. He met me halfway with a switch he had taken from the bushes behind the house. He swatted me all the way home. I kept trying to pull the bottom of my dress down to cover my legs. I hated those bushes for years. I swore I was going to burn them down.”[xcv]

Rudy had become a local legend in the Atco community, particularly among the children. Atco native Grady Bryson Jr. remembered:

“Everybody called him ‘Big Rudy’ but I didn’t. I called him Mr. York… (he) was my hero. He was back home during the off season, and I think he had a Cadillac automobile. When he came through Atco, it was like the President, you know. Us kids would follow that car as he drove through the village. It was something else.”[xcvi]

Another Atco resident, Richard Jackson, fondly recalled “Baseball was everything. We had Rudy York. We used to watch him when he practiced. He loved children and he’d say ‘Okay, boys, what porch do you want me to put it on?’ And he’d hit that ball and get it on that porch.”[xcvii]

The looming crisis associated with the war in Europe, and the United States’ eventual entry into the war, would have a tremendous effect on major league baseball. Every team would be decimated by the loss of most of their top stars to military service. The Tigers lost Hank Greenberg to military service early in the 1941 season before the United States even got into the war; Charlie Gehringer slumped badly at the plate while Bobo Newsom and Schoolboy Rowe both regressed on the mound as the Tigers stumbled to a fifth place finish. Rudy suffered a broken bone in his left wrist in mid-summer that went undiagnosed until August; he continued to play but the injury sapped the power from his bat for an extended period. His batting average dropped to .259 in 1941, but he still managed to hit 27 home runs and drive in 111 runs. His willingness to play with the injured wrist – he played in all 155 games in 1941 – took some of the sting out of what many observers considered to be a sub-par year. The Tigers finished tied for fourth that year, 26 games behind the Yankees.

Heading into the 1942 season, Rudy had his first major contract squabble with the Tigers. The Tigers, citing concerns over the war, wanted Rudy (and most of the other Tigers) to take a significant cut in salary, a demand that Rudy did not take kindly to given his willingness to play with a cracked wrist in 1941.[xcviii] The salary dispute carried over to the beginning of spring training; reporting to camp without a contract, Rudy refused to accept their last “take it or leave it” offer, and the Tigers told him to stay away from the camp until he signed. Rudy and his family ostensibly prepared to return to Cartersville; the parties finally came to an agreement before they embarked on their trip back home. Rudy signed for $9,000, but a bonus clause would give Rudy the chance to earn an additional $5,000 if he drove in 100 runs that season.[xcix] Charlie Gehringer, whose was reaching the end of his career, served primarily as a pinch hitter at the beginning of 1942 but soon left to join the Navy. With an anemic offense and weak starting pitching, the Tigers struggled all summer and finished in fifth place, costing manager Del Baker his job. Rudy also fell short of his bonus goal; he finished with a .260 batting average, 21 home runs and 90 RBI. When the season was over, Del Baker all but placed the blame on the Tigers’ poor record on Rudy and Barney McCoskey:

“I don’t mean to be putting the blame on two good guys, but it must have been plain to everybody last spring that if Barney and Rudy didn’t hit, we couldn’t go anywhere…. Barney was off about 30 points and Rudy about 50. A club like ours couldn’t stand such slumps by its best two hitters and still win.”[c]

The Tigers replaced Del Baker with Steve O’Neill for the 1943 season. By now, virtually every team in the major leagues felt the full effects of the war on their rosters. Changes in the composition of the baseball put a stranglehold on offensive production early in the year. Wartime restrictions forced the manufacturers of baseball to substitute a softer balata material for the cork in the center of the ball. The softer balata and other changes in the glue used inside the ball caused the balls used early in the season to turn much harder than usual and had the effect of deadening the ball. Rudy did not hit his first home run until May 9 in the Tigers’ fifteenth game of the season. It was, in fact, the first home run hit by any Tiger that year.[ci] By the end of May, Rudy was hitting just .235 with 2 home runs and 11 RBI. His production steadily increased as the season progressed, although he still had just 13 homers by the end of July. Then Rudy went on another of his August rampages, hitting 17 home runs that month (just one shy of the single-month record he had set in August 1937) on his way to his league leading 34 homers for the season. “Daddy used to say ‘I could hit an aspirin out of the park in August’”[cii] recalled Joe York. He also led the league with 118 RBI while hitting .271. O’Neill got the team back over the .500 mark (78-76), but the Tigers again finished fifth in the standings. Rudy finished third in the MVP voting. His 34 homers represented 48.5% of the 70 home runs hit by the Tigers that year.

Ironically, while Rudy performed at reasonably high levels compared to overall league averages during the war years, he became the object of much scorn from the Tigers’ faithful. Their displeasure began to show itself during the 1941 season, but the revelation that Rudy was playing with a broken hand allayed much of the fans’ criticism that year. Recounting Rudy’s problem with the Detroit fans, H.G. Salinger noted in September 1943:

“York got away to a bad start (in 1943) and soon found himself in a severe slump. He went from bad to worse….His fielding became as bad as his batting and he appeared to be on the verge of a nervous breakdown….The crowds at Briggs Stadium were ‘riding’ Rudy. Few players in history have ever been ‘ridden’ harder. The booed him from the time his name was announced in the starting lineup until the last man was out. They booed him every time he came to bat, every time he went after a batted ball, every time he took a throw. The razzing didn’t start this year. The fans were ‘aboard’ York last season. He took an unmerciful booing all through 1942, and the booing increased with the start of the present season.”[ciii]

Exactly what caused the fans’ discontent isn’t clear. With Greenberg gone, perhaps they expected too much of Rudy now that he was the only true power threat in the lineup, and blamed him when he and the Tigers didn’t meet their expectations. Perhaps they resented York’s holdout prior to the 1942 season, particularly given the perceived decline in his offensive production. That, coupled with a slow start by Rudy and the general lack of firepower on the part of the Tigers in 1943, may have been the source of their wrath. Perhaps they weren’t aware of the effect the new baseball had on offensive production in 1943, or of the general decline in offensive numbers throughout baseball during the war. Salsinger, who covered the team for the Detroit News, came to Rudy’s defense in the summer of 1943, taking the Tiger fans to task for their behavior towards him. Rudy, as Salsinger pointed out, had been a good citizen during his tenure with Detroit, despite his holdout in 1942. He was a nice, generally quiet fellow. He gave his best on the diamond, even if he hadn’t always been successful. He had persevered patiently when he was being bounced around between third base, the outfield and catcher early in his career. There was no doubt the fans’ treatment towards him was affecting his play. How could they expect him to perform well when all he heard were catcalls and constant jeering? Almost immediately, most fans’ reaction to Rudy changed, at least for a while, and that coincided with Rudy’s improvement at the plate in the last half of the season.

Things began to look up for the Tigers in 1944. Starting pitchers Dizzy Trout and Hal Newhouser won 56 games between them. Rudy, third baseman Pinky Higgins, shortstop Doc Cramer and outfielder Dick Wakefield led an improved offense. The Tigers went into the last game of the season tied for the league lead with the surprising St. Louis Browns. The Tigers and Dizzy Trout lost their final game at Washington, while the Browns, powered by Chet Laabs’[civ] 2 home runs, defeated the Yankees to clinch their first and only AL pennant. Rudy hit .276 with 18 homers and 98 RBI. While his 18 homers represented a significant decline in that category from 1943, it was still good for a tie for third place in the American League. Nick Etten led the league that year with just 22 home runs.

Rudy got off to another slow start in 1945 and the boo-birds came back. He didn’t hit his first home run of the season until the first game of a doubleheader on May 27. Arch Ward of the Chicago Daily Tribune noted: “One of baseball’s unsolved mysteries is the booing Rudy York still receives from the Detroit fans….The Tigers certainly wouldn’t have been a pennant threat last season without Rudy’s big bat.”[cv] Despite his slow start, the Tigers, behind outstanding pitching from Hal Newhouser, battled the Senators, Browns and Yankees for the league lead throughout the summer. Buoyed by Hank Greenberg’s return to action on July 1, the Tigers built a 4 ½ game lead by mid-July and finally clinched the pennant on the last day of the season when Greenberg hit a grand slam in the top of the 9th inning of the first game of a scheduled doubleheader to beat St. Louis 6-3. For the season, Rudy hit .264 with 18 HR and 87 RBI; his18 home runs were good for a tie for 2nd place (with teammate Roy Cullenbine and the Yankees’ Nick Etten) in the American League, behind Vern Stephens’ 24 homers. Hal Newhouser won his second straight MVP award, and the Tigers defeated the Chicago Cubs 4 games to 3 in the World Series.