Bartow Burns and an Old Flame Remembered

(A Civil War Sesquicentennial Article Series by the Etowah Valley Historical Society in cooperation with the Bartow History Museum)

Contrary to popular belief not all of Bartow was burned and not all of the burning was done by Union forces. Perhaps the greatest set back suffered by Bartow County was the burning of private property and communities. This destruction, while key to Sherman’s strategy to prevent the south from sustaining a war effort, also inflicted undue strain of the civilian population to provide for itself. Additionally, this waste set Bartow and the south far behind in recovery and competitive ability regarding manufacturing, education, prisons, health care and simply dissolved infrastructure.

As the Confederates retreated south of Cassville they hurried to the Etowah River railroad bridge with the objective to burn it and hold a line south of the river to prevent or slow Union advancement. The Confederates burned the bridge on May 20, 1864.

According to Sgt. Rice C. Bull, Company D 123rd New York Volunteer Infantry, Echoes of Battle “It (Cassville) was a fine little town with four churches, a female seminary, court house, many stores and at least 100 residence, some of which were quite pretentious. The people had all left except one family. The stores had been ransacked and wrecked and nearly everything carried away or destroyed. As near as I could see only a few private houses had been disturbed, but during the day some building containing Confederate clothing and supplies were burned. As a rule private property was not injured, however, some of the boys searched for tobacco and found a few plugs. The village did present a deserted, desolate sight.” He further writes in a subsequent entry that before leaving Cassville, he and others visited the Rebel fortifications. He remarks that they were the finest he had seen up to this point and much labor was expended to build them. He was amazed that such fine works were abandoned and not used to make a stand.

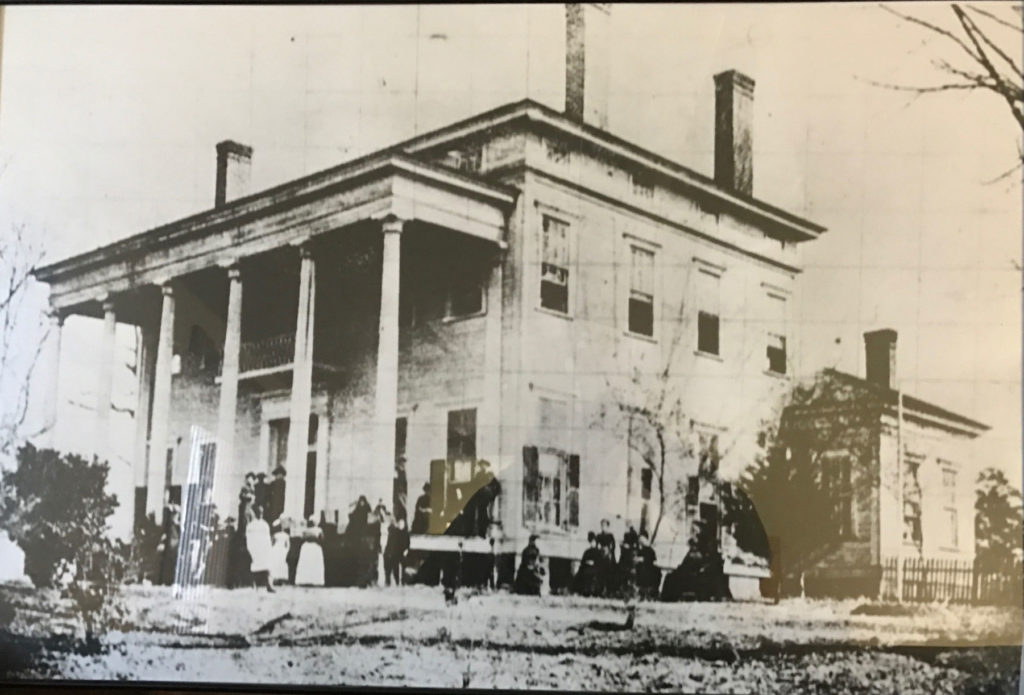

Sherman decided to rest his troops in Kingston and surrounding areas for three days before pursuing Johnston’s retreat. Sherman used the Thomas Van Buren Hargis home as his headquarters while in Kingston. It is said that in the Hargis house, Sherman planned his March to the Sea campaign. Once he realized the Confederate plan to draw him into the Allatoona mountain range he choose to go west of Cartersville and cross the river. In route he encounters the home of a failed romance, Cecilia Stovall, who he had met at West Point as a cadet. He was smitten with her and eventually offered his heart and hand. She refused his proposal and remained loyal to another cadet, Dick Garnett. She eventually married Charles Shelman of Cherokee Georgia. He built a magnificent home called, “Etowah Heights” located on the Etowah River west of Cartersville on highway 113.

Cecilia had vacated her Bartow home to avoid the Union occupation, but left a trusted negro, Joe to look after the property. Sherman spared the home and gave a note to Joe to relay to Cecilia informing her; “My Dear Madam: You once said that you pitted the man who ever became my foe. My answer was that I would ever shield and protect you. That I have done. Forgive all else; I am but a soldier. W. T. Sherman.” Following the war the home burned in 1911 and previously had been used as a bordering house to support the family. The property was purchased by the Picklesimer family.

Etowah Heights , Cecilia Stovall – Home

Sherman was particularly interested in destroying the Etowah Iron Works (also known as Cooper’s Iron Works) as a result of it producing war materials. Ingots of pig iron were primarily smelted at this location and sent to Augusta to be cast into weapons and munitions. Etowah Village was pre-war mining and iron economy. It primarily produced iron rails for the railroad, spikes, nail factory, operated a flourmill and corn mill.

Union General Schofield entered Cartersville further pushing Confederate troops south. He was reported to have camped on what is now the 1903 Court House grounds for several days. On May 21, the 104th Ohio Infantry marched toward Etowah and burned the small Depot. On the following day the 100th Ohio and other units marched into the Etowah village and burned the stone flourmills. On the same day Col. J. S. Casement of the 103 Ohio marched to the Iron Works and burned the office, rolling mill, nail factory and adjacent buildings including the main village.

Cassville had been a disagreeable town to Union forces. It’s reputation of defiance, saboteurs and support of confederate guerrilla actions created much animosity among Federal troops. Cassville was officially burned November 5, 1864 by an order issued from General John E. Smith on October 28, 1864. (Sherman signed an order on 11/8/64 to burn Cassville 3 days after it had already been burned) However, Cassville suffered an earlier retaliation as a result of a band of roving Confederate guerrillas that over took a camped Union ambulance and killed the driver and 9 straggler soldiers. The next morning the bodies were found on the grounds of the Cassville Female College. As a result, Union troops burned both colleges and several residences.

According to an 1869 local newspaper article, Cartersville was a town of some 30 businesses with a population of 700 to 1000. Scant records exist about the destruction of Cartersville, but some evidence suggests that the central business district was laid to waste with only two businesses remaining on the corner of Erwin and Main Streets and the other on East Main and Gilmer. At that time construction was primarily of wood and buildings were close together.

Wood was a prized commodity during the Civil War. Timber had been vastly harvested along the railroads to support wood burning engines. However, large quantities of wood was constantly needed to support the 150,000 combined troops in Bartow regarding fortifications, movements, bridging, cooking, shelter, heating and medical needs. Both sides pillaged stores, homes and outbuildings to survive. Often buildings were stripped of furniture and partially dismantled as convenient sources of wood. School and church pews were often used for firewood and feeding troughs. Horses were routinely sheltered in schools or churches to protect them from enemy raids and slaughter. (Cartersville’s First Presbyterian Church, First Baptist Church and Stilesboro Academy are examples of this practice) This daily need coupled with intentional orders to burn property was often responsible for claims of wartime destruction.

Orders to burn Cassville began on October 28 when the Fifth Ohio Cavalry was instructed to move up the Etowah River and burn houses of individuals that had engaged in guerrilla support all the way to Canton. Mrs. B. B. Quillian wrote “and on the 5th of November, Col. Heith of the 5th Ohio, came with about three hundred cavalrymen and completed the final destruction, which left many poor women and children without a shelter from the storms of winter which was fast approaching.”

Following this action, citizens took refuge in makeshift camps, slave quarters, tents and even sheltered next to the local cemetery. Many left Cassville and never returned to rebuild. The ruins remained for years. Bricks were eventually salvaged for new construction in Cartersville and other locations, but the destruction was so complete and spirits so broken, that Cassville perished. When peace was restored it soon became necessary to determine where the new county site would be located. The few Cassville citizens that remained did not even bid for the county seat. As a result the legislature passed an Act requiring a vote to select a new site. The following is a partial excerpt of that ACT.

Whereas, the county site of Bartow County was entirely destroyed by the Federal Army; and whereas, the former citizens of said town have declined an attempt to rebuild it; and whereas, the people of said county are desirous of locating the site at some point on the Western & Atlantic…

The two contenders were Cass Station and Cartersville. The vote was 1085 in support of Cartersville and 919 for Cass Station. Hence, Cartersville became the County Seat in 1867 and yet again, the railroad plays a major role in the outcome.

____________________

References:

The author wishes to express a sincere appreciation to Mr. David Archer for advice and use of his personal research materials to make this article project a reality. Also, a special thank you to J. B. Tate for his reviews and notes. Among other references the author wishes to acknowledge a number of works used in researching the article series including: Lucy Cuynus’ History of Bartow County Georgia, Official War Records, William R. Scaffe’s Allatoona Pass: A Needless Effusion of Blood, Frances Thomas Howard’s, In and Out of the Lines , Papers/letters from the Bartow History Museum, Joseph B. Mahan, Jr., A History of Old Cassville 1833-1864, Dr. Keith Hebert’s dissertation, “CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION ERA CASS/BARTOW COUNTY, GEORGIA” and Joe F. Head’s, The General – The Great Locomotive Dispute.

Joe F. Head

VP Etowah Valley Historical Society