The Archaeology and History of the Leake Site: A Prehistoric Ceremonial Center in the Etowah River Valley

This article series is dedicated to the archaeological details, history, and significance of the Leake Mounds and several related archaeological sites in Bartow County.

While most people in Bartow County know of the Etowah Mounds, not as many people may know that the Etowah River Valley held many more earthen mounds that were also constructed by the American Indian peoples who occupied and visited the valley over thousands of years. One of these mound sites, the Leake Mounds, is located in a large bend of the Etowah River, two miles overland and about three miles downstream of the more well-known mounds that take their name from the river. Predating the Etowah Mounds and occupied for approximately 1,000 years from circa 300 B.C. until 600 A.D., the Leake Mound site developed from a small local village into a large ceremonial center associated with a vast religious and cultural interaction network that stretched across eastern North America.

Article 1

The Leake Site: History of Discovery and Documentation

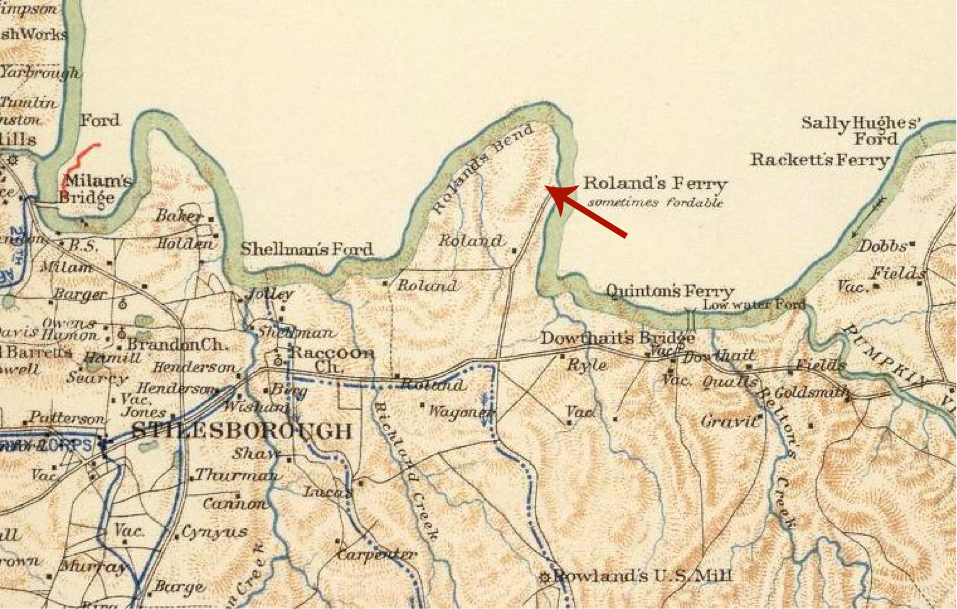

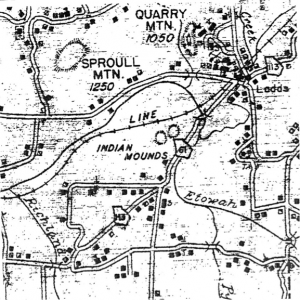

The bend of the Etowah River where the Leake site is located is known as Rowland’s (sometimes spelled Roland) Bend, after the landowner of the middle to late 1800s. This bend is labeled as such on numerous maps of the period, and a crossing/ford of the Etowah River is frequently depicted and labeled as Rowland’s Ferry (Figure 1).

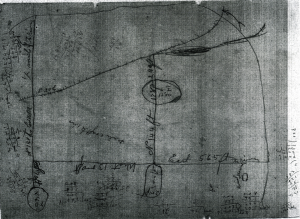

Originally known as the Rowland Mounds after the landowner at the time of the Civil War, this group of mounds eventually became known as the Leake Mounds following the transfer of property ownership to the Leake family. The earliest known documentation of the Leake site occurred in 1883 by James D. Middleton (1883) and John P. Rogan (1883), both of whom were employees of the Smithsonian Division of Mound Exploration of the Bureau of Ethnology under the supervision of Cyrus Thomas, who synthesized their findings in his reports on the numerous mounds in the U.S. that his employees were recording (1891; 1894). Rogan conducted the Mound Exploration Division’s actual field investigations within Bartow County (he also excavated at Etowah Mounds). During the archaeological investigation of the Leake site, the author acquired a copy of Rogan’s field notes for his work at Leake (Rogan 1883), which include information on the mounds and a few rough maps of the site. Importantly, one of the maps (see Figure 2) show three mounds, the river, and the railroad, as well as the distances between the mounds and his calculations. While Rogan’s documentation is certainly not up to today’s professional standards, his plan map of the site provides very significant information about its layout that was previously lost due to the razing of the mounds circa 1940 for road fill. Upon locating this map, archaeologists were then able to use GIS to tie it to the modern ground surface through a process known as georeferencing, providing them with an idea of where the mounds were mapped on the ground at that time.

Figure 2. Map of Rowland Mounds by John P. Rogan, 1883

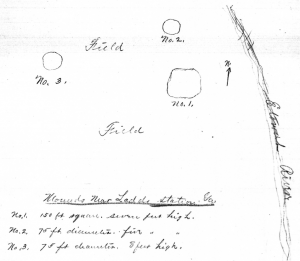

Rogan’s co-worker and colleague James D. Middleton also drew a map of the site (Middleton 1883) which also depicts three mounds (Figure 3). Like Rogan, Middleton also documented various mounds in Bartow County (and other Georgia counties), including the Leake site. From the documentation, we are unable to determine how Middleton’s work correlated with Rogan’s, in terms of the chronology and collaboration. While Rogan did excavate a portion of one of the mounds (Mound B), there is no evidence that Middleton actually excavated any portion of the site. Rather, his notes consist of a description of each mound and a map of the site (Figure 3), suggesting it may simply be that he cleaned up Rogan’s work for their boss Cyrus Thomas. While his map closely approximates Rogan’s in terms of the mound locations, the most significant component of Middleton’s documentation is the shape description of Mound C, as it is the only known for this mound.

Figure 3. Map of Rowland Mound by James D. Middleton, 1883

The next known field documentation of the Leake site dates to 1917, consisting of a photograph of one of the mounds with Ladd’s Mountain in the background (Anonymous 1917). Discovered in the files of the Georgia State Archives during the 2004-2005 archaeological data recovery investigation of the site (Figure 4), this is the only known ground-level photograph showing the site prior to the razing of the mounds circa 1940 (Keith 2010). Apart from the mound in the foreground, also visible in the photograph are the railroad and its bridge over the Etowah, the southernmost knoll of Ladd’s Mountain to the right of the trees growing on the mound, and the Ladd’s Lime Works buildings and operations on the side slope below the knoll. The prominent summit on Ladd’s Mountain corresponds to the knoll shown just northeast of the label “Quarry Mtn” on the 1992 Cartersville 15’ topographic quadrangle, and was the location of a stone wall that enclosed this summit (to be discussed in a subsequent article in this series). The railroad also emerges from behind the mound in the far right center of the photograph, just barely visible.

Figure 4. 1917 Photograph of Mound B, Leake Site (Anonymous 1917). Original caption reads:

“Indian Mound on Leake Property, 4 Mi. S.W. of Cartersville”

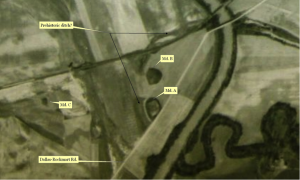

The perspective of this photograph indicates it is of Mound B, taken from the northern side of Mound A. This is suggested by the apparent proximity of the railroad to the mound, for Mound B is to the north of Mound A and is thus situated closer to the railroad. Also, the tall grass in the bottom of the picture frame suggest the photographer was standing on the northern edge of Mound A, which likely would not have been plowed due to the slope (similar to the periphery of the mound shown in the photograph). More evidence that this photograph shows the southern side of Mound B is the absence within the frame of the original course of the Dallas-Rockmart road (now Highway 113). Clearly visible in the 1938 aerial photograph (Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service 1938) seen below in Figure 5, this former road course cut into the southeastern portion of Mound A. This general course was in place in some form at least by 1876, as evidenced by its depiction in this location on a Civil War map (see Figure 1), and it also follows this course as shown on the 1940 Bartow County road map (Figure 6). This road crosses the river at the former location of Rowland’s Ferry, which appears to be in the same location as the current Highway 113 bridge. If the photograph is of the southern side of Mound A, then this road should be visible, yet it is not apparent. Thus, the photograph appears to be of Mound B.

Figure 5. 1938 Aerial Photograph Showing the Leake Mounds (Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service 1938), annotated?

Figure 6. 1940 Bartow County Road Map showing Leake Mounds

By the time the 1943 aerial photograph was taken, several changes had occurred to the Leake site (Figure 7). Specifically, the Dallas-Rockmart Road was relocated to the northwest to the location that it follows today, so that is traverses directly over Mound B. The signature of Mound B is no longer indicative of trees, but rather of open ground. At this point, the above-ground portion of this mound would have been removed. Mound A still displays a similar signature to the 1938 aerial photograph, so it appears that this mound may not have been razed by the time of this photograph. Mound C is visible as an open area, suggesting that this mound was destroyed between 1938 and 1943, likely a result of the road building activity. The ditch feature visible in the 1938 photograph is largely indiscernible in the 1943 photograph.

Figure 7. 1943 Aerial Photograph Showing the Leake Mounds (Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service 1943), annotated?

Between 1938 and 1940, Robert Wauchope conducted documentary investigations at various archaeological sites in northern Georgia, and based on a visit to the Leake site, he characterized it as “three mounds, a village site, and a lithic station” (Wauchope 1966:238). He noted that one or more of the mounds was completely leveled during highway construction so that the site was “largely destroyed”, to the point that he could not find it during his return years later in 1957.

In 1940, local amateur archaeologist Pat Wofford, Jr. “observed the destruction of the mounds and salvaged as much material as possible” (Fairbanks et al. 1946:126). Wofford seems to have alerted archaeologists Charles Fairbanks, Gordon Willey, and Arthur Kelly of the significant remains, so that they came to visit the site, resulting in a co-authored short description of the site (Fairbanks et al. 1946). While they recognized the likely association of Leake with the vast Hopewell interaction sphere that developed circa 0-500 A.D. in the Eastern Woodlands in the area extending from present-day Wisconsin to Florida, although a year prior to this article archaeologist Antonio J. Waring, Jr. (1945) was the first to formally recognize the Hopewellian connections of Leake and Ladd’s Mountain.

Leake was not the subject of any other formal archaeological investigations for the next several decades. In 1986, archaeologists with the GDOT conducted an archaeological survey through the site as part of a proposed replacement and widening of bridges Highway 113, with the area examined restricted to a corridor along the road (Georgia Department of Transportation 1987). Following this, another survey which extended through the site was conducted as part of the road widening project, and several of the individual archaeological sites that make up the larger Leake site were recognized as potentially significant for the data they contained (Price 1994). The findings of that survey led to more detailed testing of these sites several years later (Pluckhahn 1998). Testing revealed extensive and significant deposits at the sites, and it was recommended that Leake be protected from any adverse effects from the proposed road widening, and that if the site were not able to be protected, then full-scale excavation designed to recover the data which would be lost by the road widening should be carried out. Because the road design could not avoid impacting the Leake site, large-scale data recovery excavations were carried out between 2004 and 2006 (Keith 2010). Overseen by the author of this article, these excavations uncovered approximately 50,000 square feet, resulting in the recordation of extensive archaeological deposits and tens of thousands of artifacts.

Several other archaeological excavations have been conducted at the site. In 1988, 1989, and 1990, archaeologists with the University of Georgia conducted three summer field school excavations at the site (Hally 1989, 1990a, 1990b; Rudolph 1989). Another investigation was spurred by the beginning stages of construction of an 84 Lumber Company facility on the site (Southerlin 2002). After construction activity exposed artifacts and midden deposits, artifact collectors began to take items from the site, and construction work was subsequently halted while a professional investigation could be conducted. As a result, the City of Cartersville made a land swap with the 84 Lumber Company, so that this tract within the site is currently protected from development.

Figure ? shows the location of the various excavations that have been conducted at the Leake site. These numerous excavations have yielded very important data that provide archaeologists with clues and information about when the site was occupied, what activities were conducted at the site, and the various peoples that lived at or came to visit the site.

More details on the archaeological findings and what they reveal to us about the Etowah River Valley – and beyond – will be included in another installment for this EVHS series on the Leake site. Stay tuned!

Figure 8. Map Showing Location of Excavations at the Leake Site

References Cited

Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service

1938 Aerial Photograph No. IZ-3-48. Aerial Photography of the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service, 1934-1954; Record Group 145; Cartographic and Architectural Records LICON, Special Media Archives Services Division, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

1943 Aerial Photograph No. IZ-2C-52. Aerial Photography of the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service, 1934-1954; Record Group 145; Cartographic and Architectural Records LICON, Special Media Archives Services Division, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

Anonymous

1917 Indian Mound on Leake Property, 4 Mi. S.W. of Cartersville. Hu-52, Nov. 1917. Photograph mmg01-0052, State Geologist Photographs and Negative Files, Department of Mines, Mining, and Geology, RG 50-2-33, Georgia Archives, Morrow.

Fairbanks, Charles H., Arthur R. Kelly, Gordon R. Willey, and Pat Wofford, Jr.

1946 The Leake Mounds, Bartow County, Georgia. American Antiquity 12(2):126-127.

Georgia Department of Transportation

1987 Projects BHF-018-1(41) and (44), Bartow County, No Adverse Effect Findings. Letter report from Georgia Department of Transportation, Atlanta to Mr. Louis M. Papet, Federal Highway Administration, Atlanta, Georgia.

Hally, David J.

1989 Excavations at the Leake Site. In LAMAR Briefs 13:6.

1990a The Leake Site (9Br2). In LAMAR Briefs 15:4-5.

1990b Leake Site Excavations. In LAMAR Briefs 16:1.

Keith, Scot J.

2010 Archaeological Data Recovery at the Leake Site, Bartow County, Georgia. Prepared for the Georgia Department of Transportation by Southern Research, Historic Preservation Consultants, Inc., Ellerslie, Georgia.

Middleton, James D.

1883 Material concerning the archaeology of Bartow County, Georgia. Manuscript 2400, Box 2, Georgia, Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Museum Support Center, Suitland, Maryland.

Pluckhahn, Thomas J.

1998 Highway 61 Revisited: Archeological Evaluation of Eight Sites in Bartow County, Georgia. Submitted to Georgia Department of Transportation, Office of Environment/Location, Atlanta by Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc., Athens, Georgia.

Price, T. Jeffrey

1994 An Archeological Resource Survey of Proposed Widening Along State Route 61, Bartow County, Georgia. Submitted to Georgia Department of Transportation, Office of Environment/Location, Atlanta by Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc., Athens, Georgia

Rogan, John P.

1883 Notes on Mounds in Georgia. Inventory of the George E. Stuart Collection of Archaeological and Other Materials, 1733-2006, Collection Number 5268, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Rudolph, James L.

1989 1989 Excavations of Mound A at the Leake Site (9Br2). In LAMAR Briefs 14:4-5.

Southerlin, Bobby G.

2002 Archaeological Evaluation of the 84 Lumber Tract, Cartersville, Georgia. Submitted to 84 Lumber Company, Eighty-Four, Pennsylvania, by Brockington and Associates, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia.

Thomas, Cyrus

1891 Catalogue of Prehistoric Works East of the Rocky Mountains. Bureau of Ethnology,

Smithsonian Institution. Government Printing Office, Washington.

1894 Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1890-

- Government Printing Office, Washington.

Wauchope, Robert

1966 Archaeological Survey of Northern Georgia. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, Number 21, Salt Lake City, UT.

Waring, Antonio J., Jr.

1945 “Hopewellian” Elements in Northern Georgia. American Antiquity 11(2):119-120.